You should just be grateful he’s into you. That’s what I think whenever a white guy wants me. It can be someone who has walked up to me at the bar, messaged me on Grindr, or dated me for three months. Everyone has a type, I say. Just hook up with him.

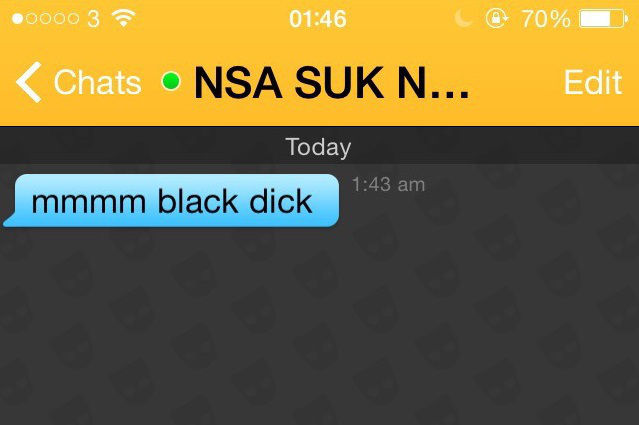

This “type” is different from most, however. It is not one rooted in who I am, but who society thinks I am: strong, dominant, well-endowed. The messages on Grindr — soundtracked by cavernous phone vibrations — always progress to the same question, just worded differently. Questions like “BBC?” or “How big?” or “You top, right?” Black queer men are so frequently placed on the bottom of the totem pole. In fact, research has shown we are most likely to get discriminated against on dating apps. But when it comes to sex, so often we’re only given the role of “dom top.”

“I wasn’t surprised when I first saw you,” the friend of a boy I had met — and kissed — said shortly after I met her. “Everytime I see *T.J. he’s with a different black guy.” She was black too, which gave the words a particular punch.

“Nice to know,” I responded, followed by a nervous laugh. I thought maybe, to T.J., who was white, I was different from the rest of the black guys he had flirted with. That maybe T.J. liked me for me. I was conflicted. I really liked T.J., so did it matter he had a thing for black guys? I had a thing for him, and isn’t that all that mattered? Later, I would scroll through my Instagram feed and see the pictures T.J. was liking. They were all pictures of young black men. Young black men like me. We didn’t all look alike, obviously, but if you were to look at us quickly enough and lump us all into a monolithic group, we did.

What are the border lines between attraction and fetishization?

Last year, Grindr released a web series video that featured two men — one white, the other Asian — swapping Grindr profiles and seeing how it changed their experience on the app. “No one’s taking the initiative in saying hi to me,” the white guy tells the camera, shocked by the decrease in messages he’s getting. “Kind of a rice queen here,” a guy messages him. Another shares his racist assumption that all Asians “are good at bottoming.” The video is bizarrely lighthearted and full of awkward laughs, and doesn’t even attempt to dive into the larger problems embedded in these messages or how Grindr could help curb them. The video ends with the white guy coming to the disappointing conclusion of: “People have preferences, and you can’t take it personally.” It’s as if fetishization is an accepted fact of life in the gay community.

I’ve encountered this same lack of sensitivity in real life too. After months of wondering about it, I finally mustered up the courage to ask my friend with benefits at the time, a white guy, if he had dated a lot of black guys before me. The answer was yes. “What?” he asked after I sighed, his voice shaky. “I like black guys and black guys like me.” It felt like I was in that scene in Get Out where Chris discovers his white girlfriend’s old pictures and sees a plethora of former black boyfriends.

Get Out was not the only powerful depiction of black fetishization in 2017. The second moment came during season two of Insecure. Lawrence meets two girls at a grocery store who aggressively pursue him. He goes back to their place and begins hooking up with them. He’s over the moon. Then things take a turn for the worst. The girls become disappointed when Lawrence climaxes and is unable to continue ravaging them. They quickly lose interest and begin naming other black guys who were able to keep going for longer. It becomes clear: Lawrence was just an object for them. The girls had not been into him for him. Any black guy would have sufficed.

Much like that Grindr video, pop culture has steered clear of conducting a deep dive into the fetishization of queer black males. There was a complete absence of white characters in Moonlight, Chiron falling in love with a person of color from the same community and brand of hardships as him. The artistic decision was an understandable one. The sameness of Chiron and Kevin was a refuge, allowing for a common understanding that never had to be spoken. I felt this same comfort with a former black partner. We would hold our hands up to each other and see who’s was bigger, or run our fingers through each other’s hair and compare textures. “You and I will always be queer and poc,” they told me once, emphasizing how the two identities would always be intertwined, almost inseparable, for us. “Stop trying to fit in.” Maybe Chiron realized this way before I did — knowing that being black and queer was already hard enough, and that trying to find love and acceptance from a queer white male carried the chance of experiencing a new kind of rejection.

I think about how Love, Simon featured its title star falling for a boy going by the name of “Blue” over email without ever seeing him. They get to know each other, Blue complaining about his distant father, Simon bitching about his overbearing parents. We learn at the very end “Blue” is a person of color. And as I write this, it dawns on me that maybe this is the reason Blue refused to reveal his identity at first — opting out of using a dating app like Grindr. Maybe he knew the host of assumptions his black identity carried. When he meets Simon, he can confidently know that Simon is in love with him for him and vice versa. There is no fetishizing going on here. They kiss, and it feels like bliss.

*Names have been changed to protect privacy.