Hong Kong is a city of inherent tension. Caught between 156 years of British colonial rule and now Chinese sovereignty, the city has benefited and suffered from its exposure to eastern and western influences, caught between political adversaries and having to find its own identity. This has always fed into the creative output of Hong Kong, particularly in the approach of young fashion designers, who have long used their work to explore what it means to be from the city.

Hong Kong’s identity has always been a fragile one. How could it not be, when it is continually moving closer to a historic moment that will change it forever? In 2047 the arrangement of “one country, two systems” expires, and the city will then be absorbed back into China. But that encroaching future became a rather disturbing present reality last summer, with the implementation of China’s National Security Law (NSL) – a sweeping legislation that almost overnight quashed any form of dissent, legitimising law enforcement to hunt down democracy leaders, and rendering the justice system arbitrary. This followed the protests that began in the summer of 2019, in response to China’s plans to implement an extradition bill. Essentially, Hong Kong has preemptively been reclaimed by China.

It is at this turning point that many young Hongkongers feel they have been presented with a hard choice: either endure indignity under the unyielding hand of Beijing, or flee to a former coloniser. Both options require huge sacrifices. Youth Ideas, a research centre under the Hong Kong Federation, conducted a poll with its members aged 34 or under. It showed that nearly a quarter of the respondents want to quit the city and work overseas to enjoy greater freedoms. This points to a potentially catastrophic talent drain for the city’s industries, including fashion.

For those young creatives that stay, there are new issues to navigate. “The challenges moving forward include how to navigate different markets around the world,” says Derek Cheng of gender-fluid brand PONDER.ER. Before forming PONDER.ER, Cheng incorporated societal messages at his student shows at Central Saint Martins. Now, he and co-founder Alex Po are on a mission with their brand to “liquify masculinity” and question societal gender constraints. “It’s about how you make use of the resources available in Hong Kong with the ongoing civil unrest and what decisions you make when it comes to voicing your opinions. Would you stand up for something through your business?”

Cheng continues: “It seems to be a very natural development for local brands to embrace what’s going on in Hong Kong and to be inspired by the [pro-democracy] movement. But it all depends on a few factors: whether they rely on the Chinese market for businesses, what their brand values are and how they approach this sensitive matter.” Moving forward, Cheng and Po are focusing more on PONDER.ER’s message of queer affirmation and incorporating Hong Kong motifs like street side ornamentation and hanging laundry into prints on luxury shirts. In their own way, they are preserving the essence of Hong Kong, while showing their customers that the city’s creative scene is far from “dead”.

The history of Hong Kong is brief in the context of modern fashion. In the early 50s, after emerging from the war, preferential tariffs combined with textile knowledge and exceptional tailoring skills from Chinese refugees contributed to Hong Kong’s pivot into the garment manufacturing industry. This attracted European brands looking for cheap manual labor and quality work, bringing an influx of new styles the city had never seen.

By the 1960s, the Hong Kong Trade Development Council was created to provide a platform for traders, designers and producers to come together. This exposure led to the transition of tastes from the Chinese aesthetics of made-to-order qipaos to the rise of western casualwear, positioning Hong Kong as a city trying to compete in an industry defined by the West.

The 70s marked the beginning of the golden era in Hong Kong as the rise of the entertainment industry – which would become the third largest in the world – prompted a demand for local designers to provide runway-worthy, couture costumes, and looks for celebrities. The world was starting to see Hong Kong as not just a financial and trading epicentre, but a cultural one.

At the same time, Joyce Boutique (think a predecessor of Dover Street Market and Opening Ceremony) was founded by Joyce Ma. She elevated the awareness of fashion in the city by bringing in boundary-breaking designers like Yohji Yamamoto and John Galliano, attracting shoppers from all around Asia. The 80s, considered by many to be Hong Kong’s most glorious years, saw legends Anita Mui and Leslie Cheung becoming influential pop sensations around Asia with their bold, ever-changing styles. Meanwhile, Vivienne Tam set off to New York to become known as the first Hong Kong designer to create an international name for herself, and Wong Kar-wai debuted his first film, As Tears Gone By, highlighting the city’s neon lights, smoky cafes and back alleys the world would come to romanticise.

The word “Hong Kong” meant something. People who had never visited the city could imagine it exciting and chic. Made in Hong Kong would evoke a sense of trust, uniqueness and style.

But the 90s saw the decline of the vibrant fashion industry as far as local cultivation was concerned. The advent of major malls spurred on egregious rent hikes that shuttered many small boutiques, serving the first blow to the city’s character. That was coupled with China’s ascent as a cheap manufacturing hub, which meant the end of manufacturing in Hong Kong. And now with the implementation of the National Security Law, Hong Kong’s reputation as a city of cultural and creative innovation is being tarnished – suffocated beneath the weight of authoritarian rule.

This is the antithesis of what today’s era of outspoken Hong Kong fashion represents. Brands these days – the ones that matter at least – stand for progressive values like racial equity, LGBTIQ+ rights, gender nonconformity and fair labor. However, this is not what the Chinese government stands for, as demonstrated with the subjugation and exploitation of Uighurs – a mostly Muslim minority group with a majority living in Xinjiang, a region in north-western China – who have been tortured and forced into internment camps. Many of the camps have been responsible for harvesting cotton used by major brands and for making disposable masks during the pandemic.

Furthermore, the NSL, in effect, is an enforcement of silence. It is quelling the voices of emerging Hong Kong creatives who want to speak out against global oppression and on the social failings of Chinese society through their work. Which Chinese designer would dare speak up for the plight of the Uighurs or for the further advancement of LGBTIQ+ rights if there are governmental repercussions? Even for this story, many interviewees declined to answer questions regarding the NSL.

And for those who aren’t careful, there will be consequences. New York-based streetwear label Awake NY, known for its engagement with social issues, showed support for the Hong Kong protests last year. In response, I.T – a multi-brand retailer in HK, who’s founder, Sham Kar Wai, is pro-Beijing – swiftly removed the brand from its shelves.

But the actions cut both ways. Pro-democracy protestors dealt their version of justice by smashing the windows of I.T’s flagship store (but refrained from stealing anything). A designer friend of mine, who wishes to remain anonymous, felt the actions were “epic” and “reflect the division in the city”. Hongkongers are very conscious about where they spend their money now, and it’s unlikely they want their money going to people who support the government.”

Hong Kong’s designers and brands will adapt to their current circumstances because they must and because Hongkongers have always found a way to persevere under harsh conditions even before the current political climate. But, the NSL will be an obstacle, not just for the city, but for China’s image as a whole.

During London Fashion Week FW 2020, designer Yeung Chin brought the Hong Kong protests to his show and blasted the anthemic “Do You Hear The People Sing?” from Les Miserables. Models walked awkwardly on one shoe and literally wore their hearts on their sleeves with dresses that featured embroidered organs. It was to symbolise the “emotional” and “unbalanced” situation in Hong Kong, says Yeung. “It will be more difficult for similar creations now. The song was banned at one of my previous shows, so at this point, we have to be very careful with our words and our actions.” He continues: “To say the least, with COVID-19 and the protests, both sales and our work emotions have been under a lot of pressure. But I’m not going to give up and neither should young people. We can still stand out by expressing Hong Kong’s story through our designs.”

One primary reason why China’s creative industries have not been able to take a substantial international foothold compared to smaller economies like South Korea is the perception of political compromise. Like tech companies, Chinese designers and brands will always be judged and perceived partly by their relationship with a government that does not value freedom of speech. The recent discussion over the banning of TikTok in the US exemplifies the paranoia surrounding the untrustworthiness of Chinese companies stealing personal data that might somehow compromise American democracy.

Make no mistake, there is no shortage of talent in China. But as famed Chinese film director Feng Xiaogang said in his speech about censorship when accepting the director of year award in 2013 presented by the China Film Directors: “Are Hollywood directors tormented the same way?” Feng asked. “To get approval, I have to cut my films in a way that makes them bad.”

Now, Hong Kong designers will have to behave the way Chinese creatives have been all along – silently defiant, subversive and finding ways to circumvent the political landscape. “It is important to stay critical and reflect on each day’s differences, rather than passively accepting the new normal,” says Terence Chan of satirical streetwear brand Feaston, which was formed in reaction to the Hong Kong protests. “There is a call for the creative scene to respond to this mixture of uncertainty unique to HK.”

Feaston responds in the best way Hongkongers know how – humour. A type of inside joke that makes fun of the absurdities of everyday life. This can be seen by their opium series of T-shirts and imagery commenting on our modern addictions to fast-fashion and technology as well as their kale print t-shirt that pays homage to a local noodle shop owner. “We like to take everyday objects and juxtapose them to put forth a fresh perspective, bringing a sense of playfulness back to the city. Our growth and development depends greatly on how we stealthily pivot from the limitations of the new social order.”

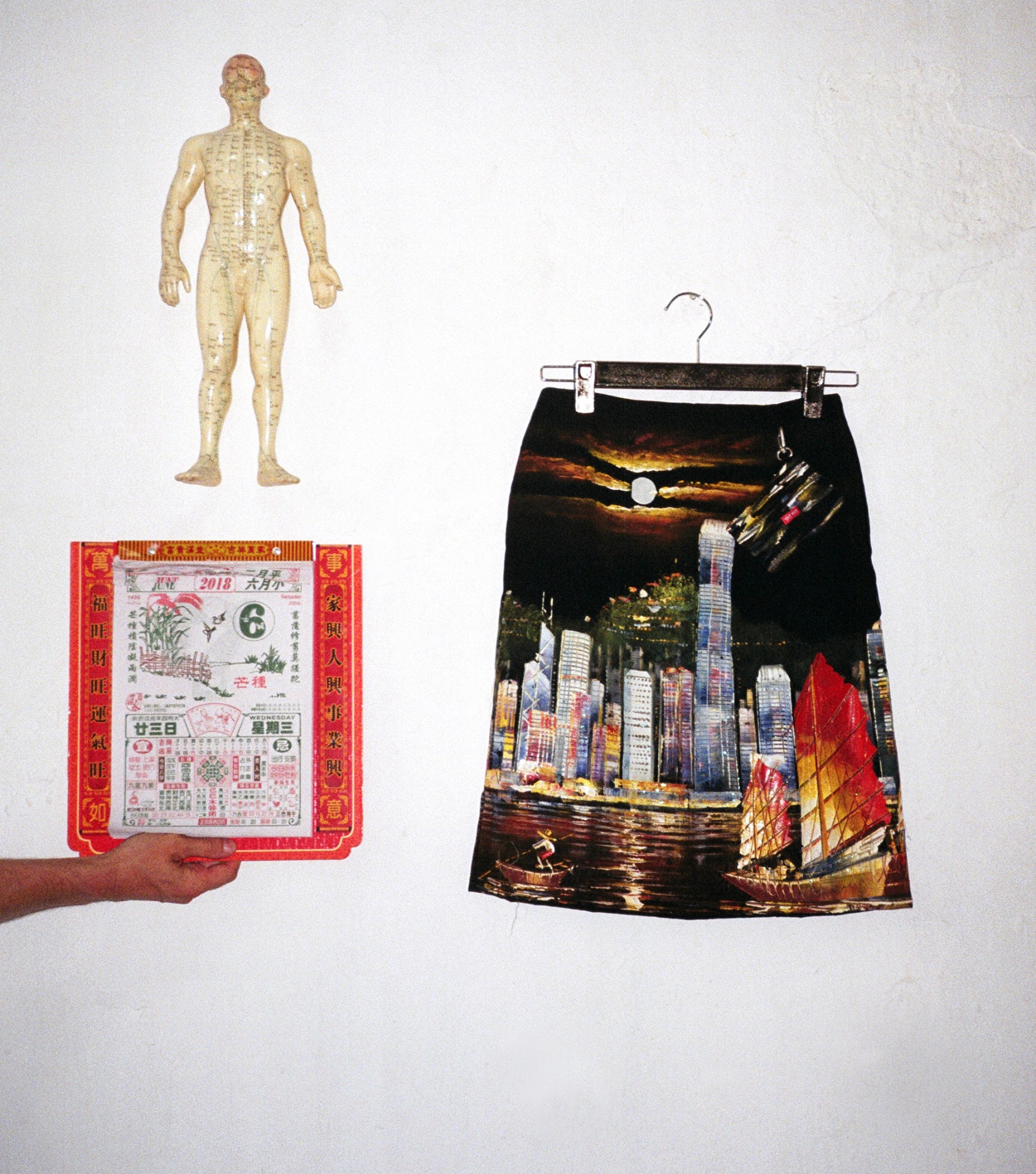

Another brand joining Feaston in mining inspiration from neighbourhood surroundings is Yat Pit. “After the Umbrella Revolution (2014’s pro-democracy protests), we started to profess our love for the city overtly,” says co-founder of the brand Onying Lai, who also acted as the Creative Director for this year’s Fashion Farm Foundation (a non-profit organisation dedicated to promoting Hong Kong fashion globally) campaign. For their sophomore collection, Yat Pit created skirts printed with the city’s skyline, and cleverly rewrote a government surveillance image into a localised, flirtatious Cantonese missive reading “checking you out”. “Hong Kong kids can be quite rebellious and clever in creative ways,” says Lai.

For a long time, a significant criticism contributing to the city’s creative decline was its lack of adequate support from educational and government entities. The local school systems are notoriously narrow-minded and relentlessly competitive, so many designers usually opt to attend prestigious design schools abroad. Then there is a cultural issue of placing importance on international brand names over local ones. Hong Kong has been in the business of importing talent, not leveraging the expertise it already has.

But that narrative has started to shift during the recent social unrest. “It untied a lot of us in terms of learning and treasuring our own culture, and supporting local businesses,” says Cheng. “Hong Kong has not been very successful in nurturing emerging creative talents, but we are seeing a change now, there’s a wave of new talents who are determined and value who they are and where they come from.”

Hong Kong’s light might be dimmed, but it’s far from dead, as many media headlines might have you assume. Fashion Farm Foundation has so far sponsored Hong Kong brands to appear roughly 150 times at fashion weeks around the world including Paris, New York, Tokyo, Shanghai and Dubai. “What’s significant about our programme,” says Edith Law, Chairlady of FFF “is we bring designers to meet international buyers and media. Despite the pandemic we still made contingency plans to provide both online and offline events to support the local fashion industry. And we will continue doing so no matter what adversity lies ahead.”

Hong Kong’s future is uncertain, but that has always been the case in the city’s history. But after weathering each crisis, the city has remained resilient. “While we are still in the system, we have to think about what we can do to make it better,” says Lai. “Do I give more anger, more judgement, more love with this collection? I choose love.”