This story originally appeared in United States of i-D, a series in celebration of diverse communities, scenes and subcultures across America.

Wandering the streets of New York’s Chinatown — down Mott, Pell or Doyers — on any given weekend, the vibrancy in the air is undeniable. Bicycles gently nudge walkers over on the street with their whir and ring. People line up down the block for their Sunday dim sum fix. And the faded yellow, pink and red facades welcome visitors with a comfortable, worn-in familiarity — one that’s been around for a long, long time.

In 2021, the World Population Review reported that there were 1,186,606 Asian Americans living in New York City, and the city is also home to the largest Chinese population outside of Asia. After the first wave of Chinese laborers were brought to the US in the mid-1800s, many moved from San Francisco to New York after the 1877 riots, establishing what’s known as Chinatown today. Despite growing anti-Asian sentiment, the number of Chinese, Japanese and South Asian immigrants grew steadily throughout the late 19th century — ultimately culminating in the Immigration Act of 1917, a new law that effectively banned all immigration from Asia to the US.

During this time Asian Americans across the country fought tirelessly, unable to reunite with loved ones across the Pacific or even own land in the US because of their ethnicity. Meanwhile ethnic enclaves like Chinatowns expanded in size, fascinating the white population as a place of tourism while simultaneously becoming the target of racist attacks. The Immigration Act of 1965 — a historic part of the civil rights movement that reopened immigration from Asia to the US — helped shift that dynamic by greatly increasing South and Southeast Asian immigration, ultimately creating the diverse Asian American population we know today.

Given the wide breadth of the Asian American experience and identity, it’s impossible to say that any one cultural space can wholly define our community. But at the same time, spaces like New York’s Chinatown feel sacred in a way that’s hard to describe: they carry the tenacity of a community coming together to rebuild over centuries, no matter how many times they were burned, attacked or destroyed. They reverberate with the radical resistance of a love and joy of a people who lived in fear of being killed for no reason other than their race. They represent the deep, ancestral resilience of our people — something that we won’t ever let others take away.

As we return to a moment where anti-Asian violence is at an all-time high (there have been over 3,800 reported instances of anti-Asian assault since March 2020), it’s hard not to be reminded of the importance of keeping Chinatowns — and other spaces Asian Americans regularly occupy — safe. As we encourage all who are able to support Asian communities across the country, we also want to uplift our people: to highlight our strength and our humanity.

Here, New York City’s Asian American creatives share their stories to reclaim and redefine the independent and boundless beauty of their community.

How has being in New York impacted your work?

Leo Nguyen: New York has been everything to me. I don’t know how I’ll ever be able to pay her back, honestly. This city can be uncomfortable and even at times suffocating, but it helped raise me. I’ve unlearned so much toxic bullshit that was force-fed to me growing up in a small suburb, by simply being here. I’ve met the kindest, most creative people and I continue to be enamored by them. I want to take everything I’ve learned and continue to learn, and pass it to the next generation of New Yorker transplants.

Michelle Zauner: It’s provided me with such a vibrant and creative network. I’m so grateful to all of the collaborators I’ve met here and the heights they’ve lifted me to in our work.

Chella Man: Coming here from a tiny town in PA, I feel like I have time traveled hundreds of years into the future. Queer people walk down the street holding hands, sharing a kiss, wearing queer slogans proudly. I have had the opportunity to connect with a disabled, BIPOC community as well. Being here has allowed me to find myself quicker than I would have ever been able to in Central Pennsylvania.

Lulu Yao Gioiello: Having grown up here, I feel like there’s a special diversity within public education and a definite exposure to the arts and community. This ‘melting pot’ of culture and class has definitely influenced my work.

Gia Kuan: New York has been my dream since I was a child. I moved here in 2010 having never been to the city before (except for the one week I was here when I was five with my parents). I hopped on a plane from Australia with one big red suitcase [and] never looked back. I did always romanticize New York City as a place where anything can come true, where I can start from scratch and form my own identity and live the American dream; it’s not without its challenges. But I was completely inspired by many of the underground cultures and subcultures I encountered during my time here, and I completely thrive and love every second of this energy. I think I’m a hopeless romantic but I do love New York. I am constantly inspired and New York has taught me to be more fearless.

Jaeki Cho: My family moved to New York when I was nine, so my adolescence, the pivotal years of my childhood and my adulthood has all been shaped by New York. I grew up in Queens, which is a very diverse place — the parts of Queens that I lived in, like Jackson Heights and Elmhurst and Flushing, are like some of the most diverse [neighborhoods] in the entire US. From the way I speak to the way I identify what’s good or bad — a lot of that measurement is derived from my roots and cultural experiences I’ve accumulated in New York. New York City’s a place where you’re forced to have interactions with people that might be different than you: you’re riding the train, riding buses, walking everywhere. All of that impacted how I perceive life, and life is a reflection of your creative work, right?

What was it like growing up as an Asian person in America?

Chella: Joyful. Elucidating. Delicious. Cared for. Frustrating. Loved.

Leo: It’s a complex feeling. You’re forced to feel this sense of otherness like you don’t belong, while also recognizing as a natural-born American that you have nothing else to fall back on. It wasn’t until recently that I came to the understanding that being an immigrant in America is the most American thing you can experience or feel.

Gabe Bergado: I was lucky to grow up in an area and go to a high school that had a lot of Asian Americans. I didn’t think too much about identity as a kid. My dad had a lechon business where he’d cater the Filipino delicacy for events and parties all over Southern California. I would go with him on the delivery runs and it was an adventure getting to meet Filipinos from all over Orange County, Los Angeles, San Diego and more. As a teen, the diversity in my friend groups gave me the opportunity to experience many of my friends’ own ways of being Asian American, too. After class we would get boba, Starbucks, pho, In-N-Out, burritos, banh mi or whatever we felt like. I remember after taking the SATs we got Korean BBQ one time. Remembering this, I am once again reminded of how food has been a strong connection to my Asian American identity.

Humberto Leon: I’ve always felt privileged and tried to use our space to lift others. Growing up as an Asian American, you’re fed all these stereotypes which seem good at times and horrible at others. You just kind of accept it. I’ve been feeling anti-assimilation and wanting to bring my own culture to my America, and that’s a big switch [for me]. Creating a space where I can support my BIPOC brothers and sisters is the place I want to be at.

Danny Bowien: I was born in Korea, adopted at the age of three months and grew up in Oklahoma City. My father worked at the General Motors automobile plant, and my mother had a newspaper route and worked at the food pantry at our church. My childhood was very suburban, I remember playing a lot of Nintendo and rollerblading. We went to church three to five times a week, which really informed a lot of our activities. I think that my situation as a Korean adoptee with white parents made a lot of people uncomfortable, and I remember from a young age constantly telling people what they wanted to hear, rather than what I actually felt. They would always ask me about my ‘real parents’ and I would answer that my adopted parents were my real parents and that I had no interest in learning about my birth parents. As I have gotten older, I can acknowledge why I reacted that way and the need to make other people feel comfortable in my presence. Having a kid has changed my point of view on wanting to learn about my birth parents and Korean culture.

What are some challenges you’ve faced as an Asian American creative?

Jasdeep Kang: I feel like it’s challenging when I’m boxed in [and] I really don’t like being boxed in. I think what makes the Asian diaspora so unique is that each person has their own class, gender, accessibility and racial differences. It’s challenging when we are typecast as one because our differences offer so much complexity and beauty. I love being able to honor those complexities and those differences, so it’s challenging when there is no room for that, and when my own grey areas of existence are not respected. For example, the pronunciation of my name. I have had so many challenges and internal anxieties with how to introduce myself. As I’m growing older I have more confidence to repeat my name, Jasdeep, and be open to other people’s curiosity, but it’s definitely been challenging to get where I’m at now.

Yulu Serao: In past roles as an Art Director, there were stereotypes like, ‘you have such great attention to detail’ that were thrown at me, but this always made me laugh because if you really know me, my parents aren’t Asian. I’m adopted.

Anna Theroux Ling: I wouldn’t say this is a challenge necessarily, but with the nature of working with different people all the time, some people are surprised or confused that I can speak English fluently when I say I grew up in Japan.

Gabe: A major one is just reminding people that we’re not a monolith. The Asian American experience is such a varied spectrum. I think that because there’s certain narratives that continually get put in the spotlight, there are certain archetypes of being Asian that are deemed the most prevalent or most interesting. Someone who is of Southeast Asian descent is going to navigate the world differently than someone who is from East Asia. An Asian American teen from Minneapolis is going to have different things to say than one from Los Angeles. There are things that connect us to one another underneath the umbrella term Asian American, but there is a wide breadth of differences as well. Personally for me, a challenge is just figuring out where I fit as someone who is both multiracial and gay and how those intersectional identities influence my own work.

Michelle: I feel like the challenges I’ve experienced as a woman in a largely male dominated field is largely just exacerbated by my race. [Like] just not being taken seriously.

Jaeki: Because we come from first generation or 1.5 generation immigrant backgrounds where the pursuit of happiness is oftentimes tied to stability, the expectations of the household are that we find occupations that are stable. I know the trope, and I hate it when every creative person says, ‘Oh, my parents wanted me to be a doctor or lawyer,’ because it kind of stigmatizes [those professions as if it’s] a bad thing. But I’d say stability is expected, not just in Asian American households, but also in a lot of immigrant households. And as a result, artistic endeavors are not something that first generation immigrant parents are familiar with because they don’t have examples that they’ve experienced firsthand.

What does family mean to you?

Gabrielle Widjaja: Family is whoever you choose. I think in Asian culture we’re not taught to have that choice — blood is always thicker than water to my parents, no matter what. I have trouble with this belief because it allows for a lot of abuse, whether emotional, mental or physical, to be perpetuated within families, and for older folks to feel like it is normalized or just something you have to put up with because we’re family. My parents always said that friends would never take care of me the way that family would, and I honestly do not think that is true. In a broader sense I think that family is also community; I prize the communal nature of our people over all because we have so much compassion, generosity and belief in the collective, which is refreshing since growing up in the West can make one increasingly more individualistic. Sometimes I feel like that part of me is so often at odds with the idea of sacrifice for the family (the collective). Family, above all, is complicated and that’s okay.

Michelle: Outlasting singular human life.

Danny: Family is complicated but can also be extremely fulfilling. I always thought once I had my own family I would really understand what it meant, but it revealed things to me that were unexpected. My son’s mom and I are separated, but we’ve worked really hard to remain a family. It’s not easy, but I’m grateful for that and those who are close to me that I consider to be family.

Gia: Family is everything to me — even though I grew up very independent and have lived many places by myself, we have a very tight-knit and trusting family so I do talk to both my parents everyday. My father is like a boss, my friends are obsessed with him but also fear him because he looks like he could belong in a mob lol but really he just really likes to cook and is the best chef in the world. My mom is incredibly funny and likes to laugh. Additionally, I was very close to my late-grandparents on both sides. That’s something that I really treasure thinking back. My grandparents raised me until I was 10, really, because my parents worked so much to make ends meet. Through my grandparents I learnt tradition and many many stories about my ancestors which I’m so grateful for today.

Gabe: Family means a lot of different things to me. Of course they’re my ride or die. I’d do anything for them. It also means the generations that came before me that sacrificed so much for the opportunities I have today, something I’m eternally thankful for and have become more cognizant of as I’ve become older. Beyond the people that are flesh and blood and those that raised you, family also means the support system that you find as you get older. Especially as a queer person, I’ve seen how powerful chosen family and the friends who you surround yourself with are.

Humberto: Family is permanent, it’s a structure that can’t be toppled. I’m fortunate enough that I have a huge family. I’m also fortunate because I have a chosen family of my queers and BIPOC brothers and sisters, an extended family that some people ONLY have. I’m lucky, I have both. Ultimately, family means they accept you for everything you are.

In light of the current rise in anti-Asian violence, what do you hope the future looks like for Asians in America?

Humberto: I hope that Asians in America will feel the strength to stand up considering we are constantly meant to be silenced. With the ‘model minority’ status that was labeled on us, it’s a farce that makes everyone think that all Asians are well off, subservient people. Asians make up some of the poorest people in America, if you look at the statistics. This model minority theory also creates a divide between our Black and brown brothers and sisters. Unless we can really change racism and support a Black Lives Matter movement holistically, we cannot move forward in America. We have to address the root of the problem, which is systemic racism — then a new day can happen for all minorities. We need to all ban together to fight injustice and learn to protect each other. It’s the only way.

Gabrielle: I hope that [our] future is one where we are no longer under attack, of course, but also a future where our conversations move past representation in the media and focus on long-standing historical context of our oppression, teaching our community to stop being anti-Black and pro-police, unlearning the model minority myth and thinking critically about what our narrative as Asian Americans is/having clarity on what it is that we are demanding besides to simply “stop asian hate,” which is a pretty reductive statement about our myriad of problems as a community. Overall I wish for prosperity and health, the wishes of our elders who came before us and staked a small piece of this country for us.

Lulu: I’m so happy to see people addressing suppressed feelings, or feeling strong enough to speak out vulnerably and passionately. I hope we can connect across cultural boundaries, and realize we should all be unified to protect and enhance the lives of not even just Asians (North, East, South, West), but all marginalized people.

Jasdeep: I really think collective empowerment is here — it’s like we can’t really look away from it at this point. The future is self respect, self compassion, loads of empathy, and breaking down and grieving intergenerational trauma. I hope everyone is rooted in a strong purpose and realizes their callings and gifts. I hope people will be operating from their heart energy and deep-rooted love.

Leo: So much of the Asian experience has been ignored and dismissed that all I want is for us to feel recognized, acknowledged and respected. To feel a sense of empowerment that there’s not a space that we can’t be in so long as we identify with it. I hope that the next generation of Asian Americans can be proud of the things that make them who they are. Our heritage matters, our stories matter, we matter.

Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more culture. Tune into United States of i-D here.

Credits

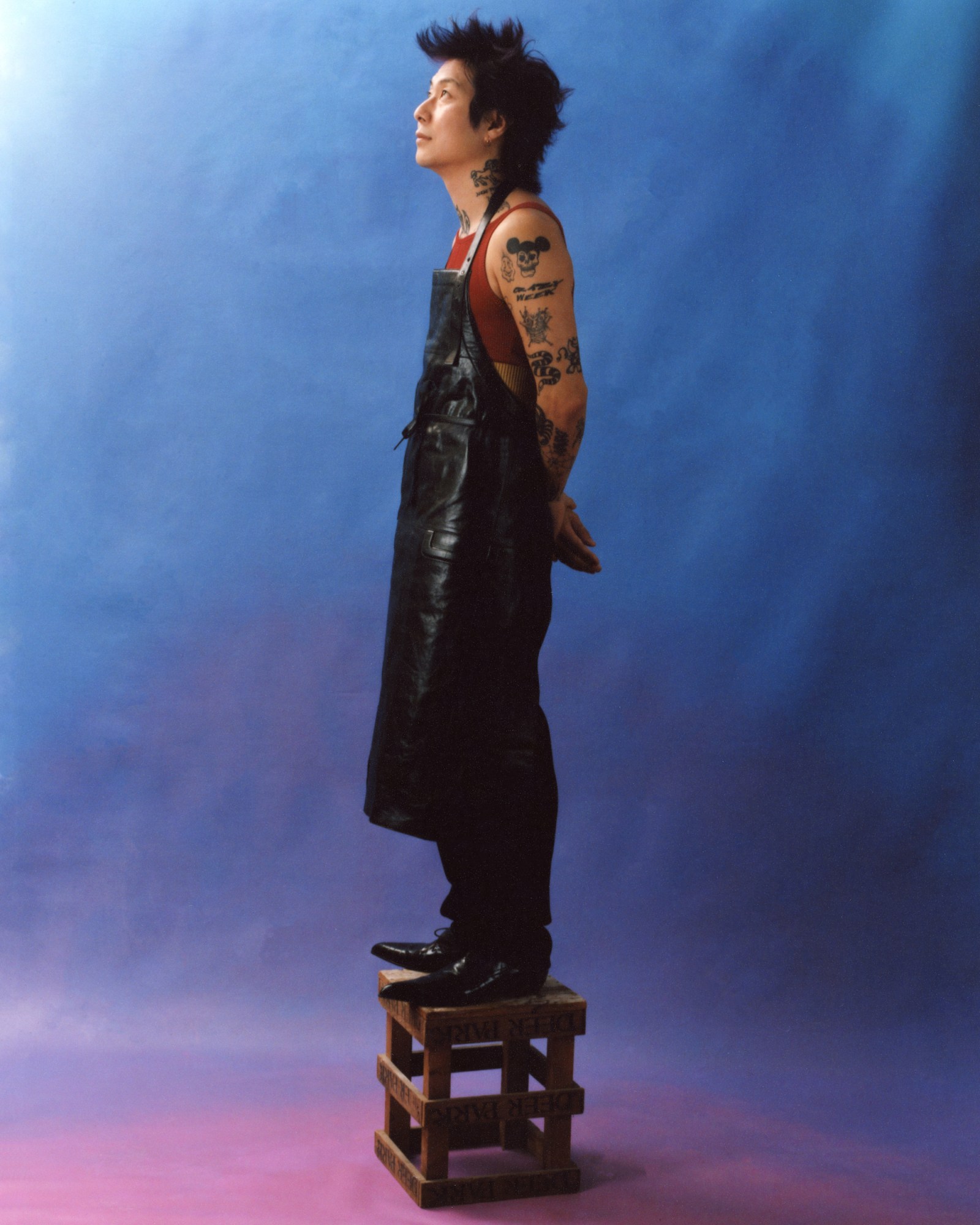

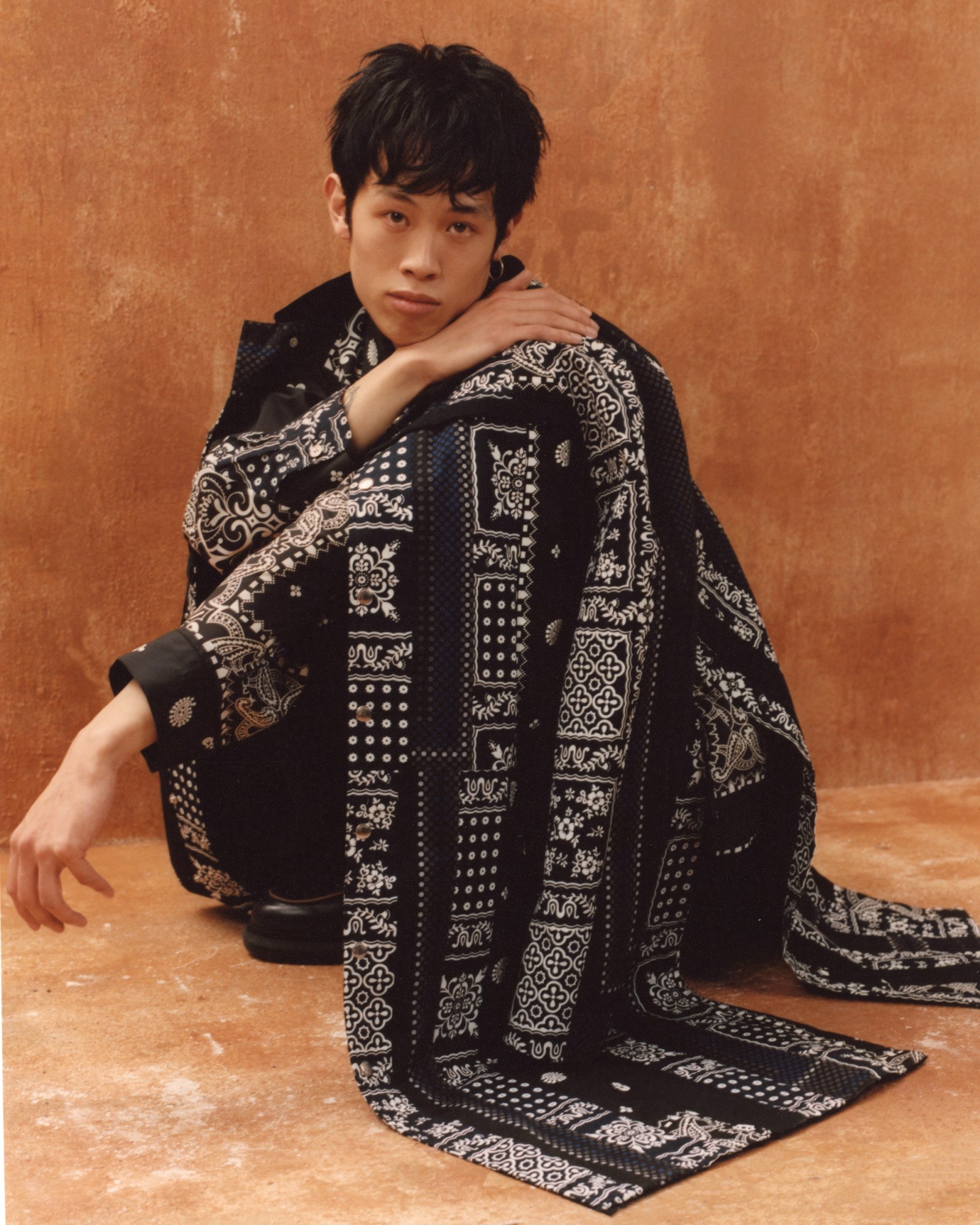

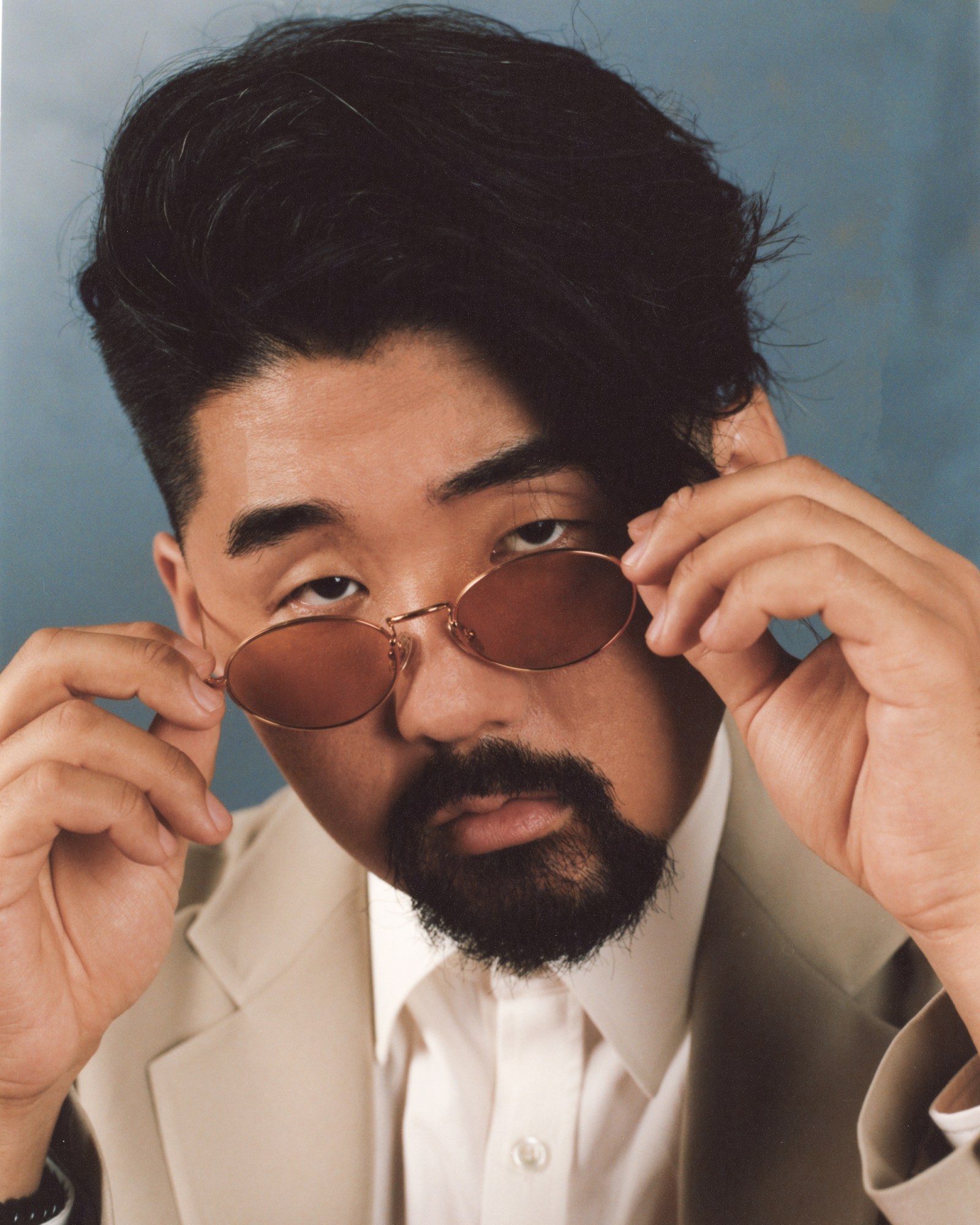

Photography Alexander Cody Nguyen.

Styling Brandon Tan.

Makeup Miki Ishikura using Mac Cosmetics

Hair Chika Keisuke

Production Design Michelle Lee Johnson

Producer Zoë Glaser

Photo Assistant Benji Geisler

Styling Assistant John Park

Special Thanks to Francis Nguyen, Tina Pham and Quil Lemons