In the center of Pristina, Kosovo, sits a wounded architectural symbol of brotherhood between Albanians and Serbians. The partially burnt, brutalist shell of the Palace of Youth and Sports is nicknamed the “Boro and Ramiz”, in honor of the two Yugoslav Partisans who lead the local struggle against fascist authorities in World War II. Despite MoMA’s current exhibition celebrating this architectural era, the Boro and Ramiz — along with many of monuments to Yugoslav “brotherhood and unity” — has lain in disrepair since interethnic conflicts tore apart the country in the 1990s.

In late summer 2012, a group of young artists repurposed this historically loaded space — and its namesakes — to a functional, yet radical end. Over two months, 33 happenings around Pristina culminated in an “interactive mega-performance piece” in early September with over 2,500 people in attendance. Titled “PRISTINË—mon amour,” the series sought not only to push back against the unresolved ethnic tension coursing through Kosovar society, but challenge conservative attitudes towards two other groups: women and sexual minorities. To end the performance, a phalanx of seven bruised cheerleaders marched down the stage shockingly unfurling a drawing of Boro and Ramiz French-kissing passionately. Anticipating blowback, then 23-year-old curator Astrit Ismaili told the New York Times “If you want to do something here, you have to invent your own path.”

Six years later, now living in Amsterdam, Astrit recalls their work from this year as a turning point not only for their artistic career, but for their self-awareness. Creating an artistic platform to express themselves as a queer boy in a conservative environment was a “survival strategy,” Astrit tells me. Opening up on Instagram recently, they write:

At that time, the wounds were still bleeding from the 1999 Kosovo war. Sexuality was not a priority for most, but I was growing up. I needed to choose in which direction to go. I didn’t have a discourse and I didn’t know how to defend myself, but my body was telling me that I had to set it free from the expectations. Having a male body, but incapable to take the role of a man, I protested. I protested alone not knowing if there are others that feel the same way.

Despite Kosovo’s strides towards reconciliation and development since the conflict, conservative social mores still dominate. Mired with a stagnant economy, low-wages, and visa restrictions, progressive social issues like gay rights are often an afterthought in this 90% Muslim country. Astrit is quick to point out, however, that a generational shift is coming: Kosovo has the youngest population in Europe, with a whopping 70% of its population under 35. Though shy to assert it, back in 2012 — years before Pristina’s first pride march in 2016 under heavy police protection — Astrit was one of the first artists to blatantly thrust issues of gender and sexuality into public space and discourse.

When I first saw Astrit perform at the DIY art-space Sociëteit Sexyland in Amsterdam-Noord, they were chained to the other performers donning a white dress, a metallic purple wig and a 9-month-old belly-bulge — a reoccurring alter-ego called the “Pregnant Boy.” Digging further, I start noticing Astrit’s reference points in the deep tradition of performance art in Yugoslavia. About halfway through a performance called NEMESIS last February—an “emo pop experience that explores the vulnerability of the voice in relation to self-balance, destruction and sexuality” — Astrit plays the knife game. Jabbing haphazardly between their fingers, blood drips to their chant of a 2000s-esque-emo ditty—an action directly recalling Marina Abramović’s 1973 Rhythm 10 that similarly tested the physical and mental limitations of her body in performance. In the 2011 series that won Astrit a spot in the ISCP residency in New York City at just 22 (“today I woke up I walked thoughtfully I was calm and free”), they posed naked around Pristina in broad daylight, testing the social limits on their body’s place in the public realm. As with the streaking performances of Croatian artist Tomislav Gotovac in Zaghreb decades earlier, Astrit ended up arrested. Laughing, they remember, “Since I was the first person caught naked in the history of modern Kosovo, they didn’t know how to treat my case, so they just fined me 500 euros.”

Surprisingly, curating PRISTINË—mon amour in 2012 was not Astrit’s first time performing at the now-damaged Boro and Ramiz. A decade and a half earlier, a singing contest at the space launched them and their sister to child pop-stardom. In the midst of conflict, a wave of children’s groups swept Kosovo — youthful voices offering some measure of hope. “My mom believed that music could help heal a people experiencing an extreme event like war,” Astrit recalls. In line with their mother’s belief, a fixation on the human voice remains a core element of their work. Just as it is a salve for political wounds, music too can address personal struggles, like the homophobia, sexism, gender dysmorphia they witnessed growing up.

Yet, in our conversations, Astrit conveys a subtle vexation in the way critics interpret the link between their art and identity. Although driven by a clear desire to give voice — literally, through song—to young Kosovars struggling with similar questions of identity, Astrit approaches such categories playfully rather than earnestly. In recent years, in fact, their work has focused less on reacting to the oppression of real-life identity politics, and more on figuring out how to transcend them altogether. This more esoteric work lacks the immediate appeal of earlier political performances like “We Are Broke,” a striking public choreography in Pristina’s marketplace speaking to the seeming “impossibility of youth activism to change political and economic situation in Kosovo.” Yet, this shift is motivated by perhaps the most compelling concept in Astrit’s work: the right to be undefined.

Moving to Amsterdam, “there was a pressure to label myself and my work in a way that my cultural background and political situation in Kosovo would be an intrinsic part of my art practice,” Astrit recently shared with me. Oddly, art communities in the West seemed to want to consistently define Astrit within the very victimized categories they were trying to escape. Lacking any immediate threats to their sexuality and gender expression in the Netherlands, yet boxed into this one-dimensional narrative, an uncomfortable dissonance set in. “My alienation”, they reveal, “inspired me to create new worlds and personas that go beyond my personal history, reaching universal issues.”

Enter “The Pregnant Boy,” the gravid yet glam alt-diva who first invited me into Astrit’s imaginative universe that evening in Amsterdam. According to Astrit, ‘The Pregnant Boy’ doesn’t have a name, a race, a job, a gender — basically it don’t belong to any category.” Without means of social classification, the Pregnant Boy exists in an alternate reality — a foil to the oppressive social structures that define our real-life existences.

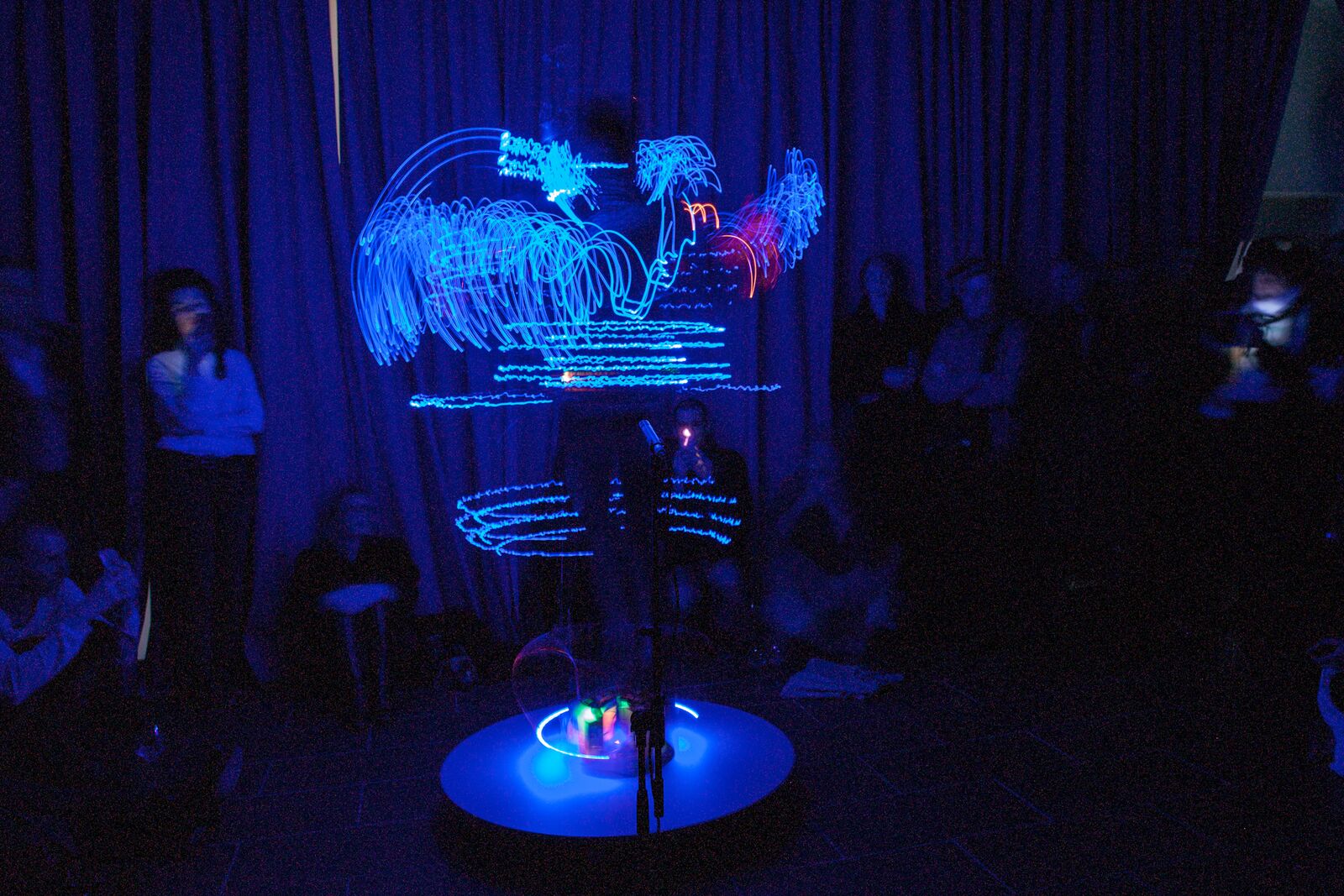

This summer, Astrit went home to Kosovo to build “THE NEW BODY.” A form-fitting contraption of metal, blue lights, mesh fabric and motion-sensors, one could best describe it as a sonic exoskeleton. Translating the body’s gestures into a cacophony of voices, the wearable-tech piece is supposed to “imagine new and utopic ways of thinking about how bodies inhabit and occupy space.” When I speak to Astrit in August, however, its assembly in Kosovo is stalled. Local craftsmen are daunted by the technical aspects of the project, let alone the work’s conceptual basis in a progressive discourse foreign to them. Here, again, a body was at stake. Working intensely over a month in Pristina, Astrit transcended the personal, cultural, and political divides that might have estranged him from these older Kosovar men a few years ago. A shimmering and singing NEW BODY emerged. As THE NEW BODY toured around Europe this fall, it was hard, as a viewer, to not desire similar transcendence beyond whatever identities or perspectives might divide the rest of us too.

Astrit will perform THE NEW BODY at Lost & Found Oude Kerk in Amsterdam on December 21st and at KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin on January 15th, and as the “Pregnant Boy” at Robert Grunenberg in Berlin on December 15th, 2018.