Every six months or so, the internet turns a new piece of Black Vernacular into a hashtag. One year its #TheCookout. The next, #Sidechick. The slang typically originates among black social media users — used as the building blocks for formulaic memes and impassioned The Shade Room debates — and, suddenly, enters popular (see: white) usage. Over time, the word becomes a little bit less ours, going down a cultural path similar to “ratchet.” That is, used overzealously and erroneously. This year, “auntie” is that word.

What is an auntie? Or, better question, who is an auntie? It depends on who you ask. But some universally agreed upon aunties are: Oprah, Tracee Ellis-Ross, Mrs. Tina Knowles-Lawson (don’t you dare forget the mrs!), and Jennifer Lewis. Women who will two-step to an Xscape jam, throw back a wine cooler, and give you unsolicited dating advice.

The term’s newfound popularity can largely be credited to Rep. Maxine Waters, who achieved internet fame in 2017 with her inimitable “no-fucks-given” attitude (a mandatory auntie quality). But the onslaught of memes and the rise of #AuntieTwitter has seen “auntie” become divorced from its racist, colonial past. Remember Aunt Jemima?

A new Brooklyn exhibition, Aunty! African Women in the Frame, 1870 to the Present, can be seen as an attempt to add depth and understanding to the colloquialism. Curators Laylah Amatullah Barrayn and Catherine E. McKinley use the term as a launching pad for examining how African women have been captured. Over 100 photographs — from vintage family snapshots to contemporary high-art portraits — of African women are on display. Women who were, or would become, aunties.

Laylah says the exhibition’s title came about during the late stages, when the women were deciding which images to include. “We would pull out photographs and Catherine would look at the women and say, “This is Aunty! And that’s Aunty!’ We thought, well, we should call it Aunty.”

“Auntie has always been a troubling word for me,” Catherine tells i-D. “As a child, I hated when people called me it. But in Africa, it really is a term of respect. I felt like I embodied ‘auntie’ when I visited with my kids. All of a sudden I wasn’t ‘sister.’ I was ‘ auntie.’”

Catherine goes on to discuss how “auntie” is primarily an assigned identity and role. We may be calling Rep. Maxine Waters auntie, but when has she ever publicly called herself it?

”I think about all the darker meanings of it,” Catherine says, “like the homophobic connotations behind Auntie Man in Jamaica, and the ways it also carries over into men’s lives as a pejorative. It’s very burdened. For a woman who does not want to be an auntie, or may exist outside of gender norms, it’s also a very weighted term.”

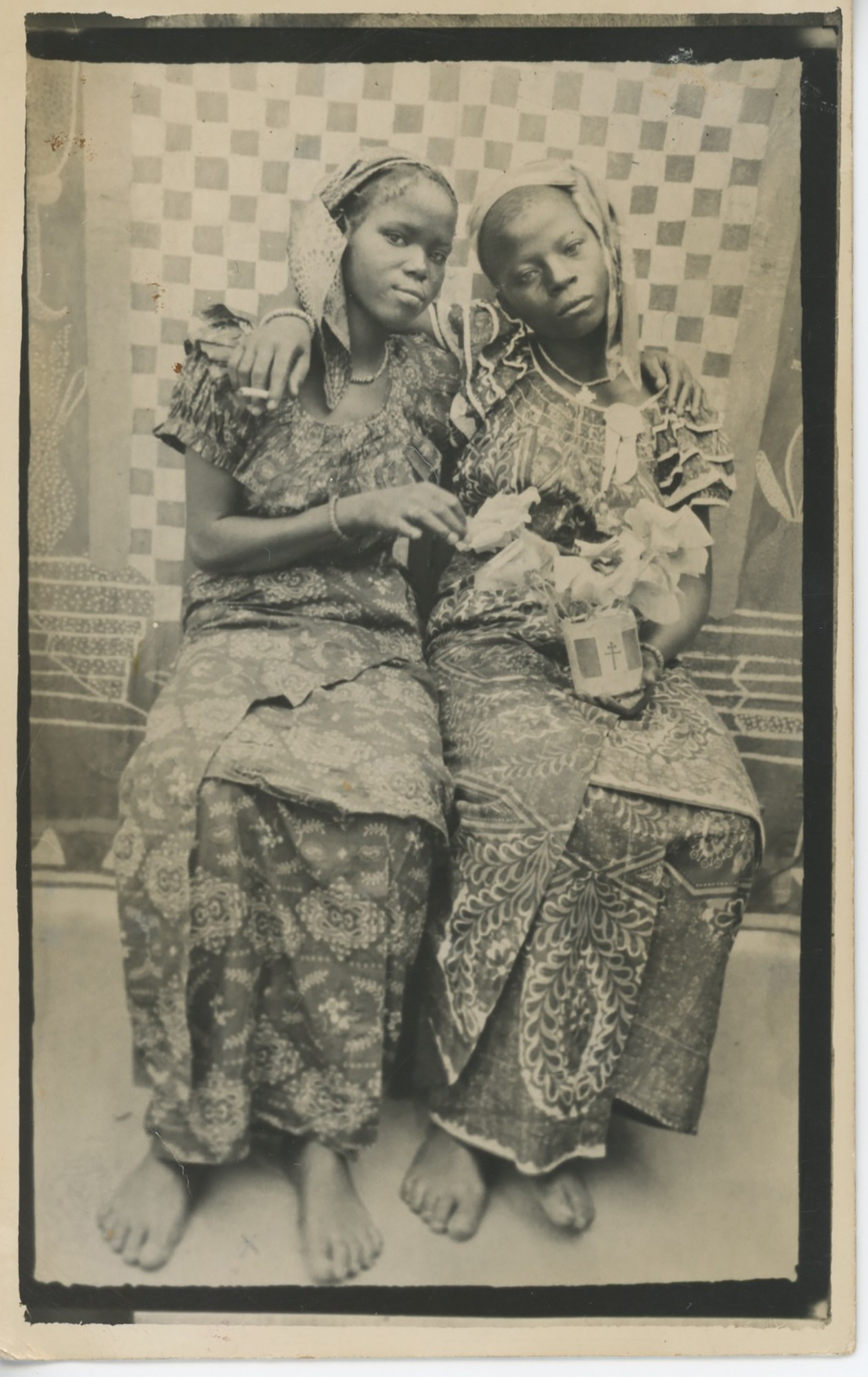

This reckoning with agency, identity, and ownership is present throughout Aunty! Remember, these images are from the past. And the past is not pretty. Many of the images were produced explicitly for the white gaze, taken during colonial occupation of Africa. A single wall is dedicated to this period, a time when African women were not in control of how and when their image was taken. There are photos of them being shown off at European “human zoos.”

When I ask Catherine if it was hard to find these historical images of African women, she responds with a quick, resounding no. “It was part of colonial propaganda to display women’s bodies in this particular way,” she explains. “A lot of the images were used almost as a kind of ‘soft porn’ among the colonists. My intention in collecting is to look past this and reconstruct these women for who they were. So when I see the images, I don’t miss what’s going on, but I’m kind of like looking them right in the eyes, thinking about who they were.”

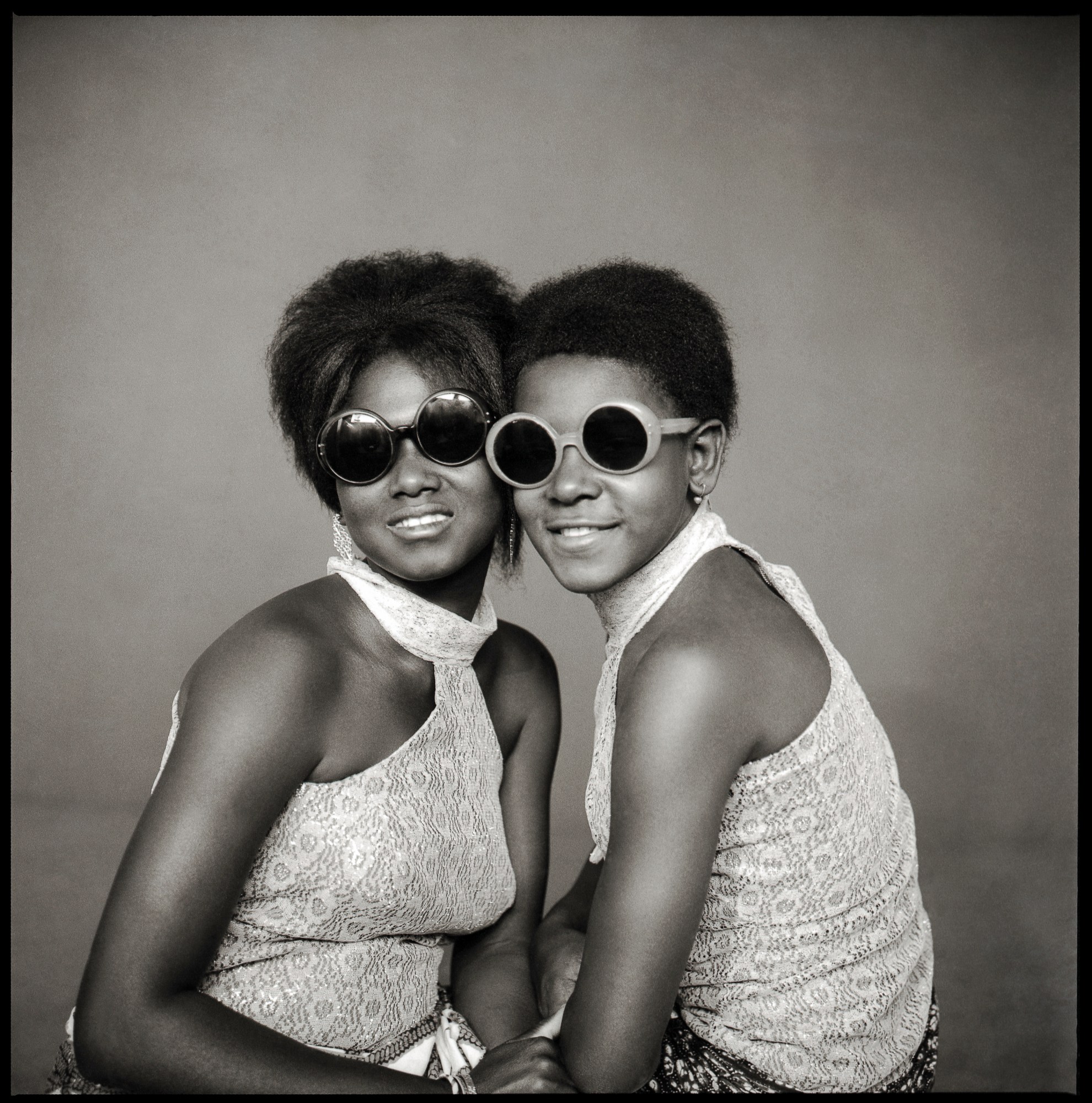

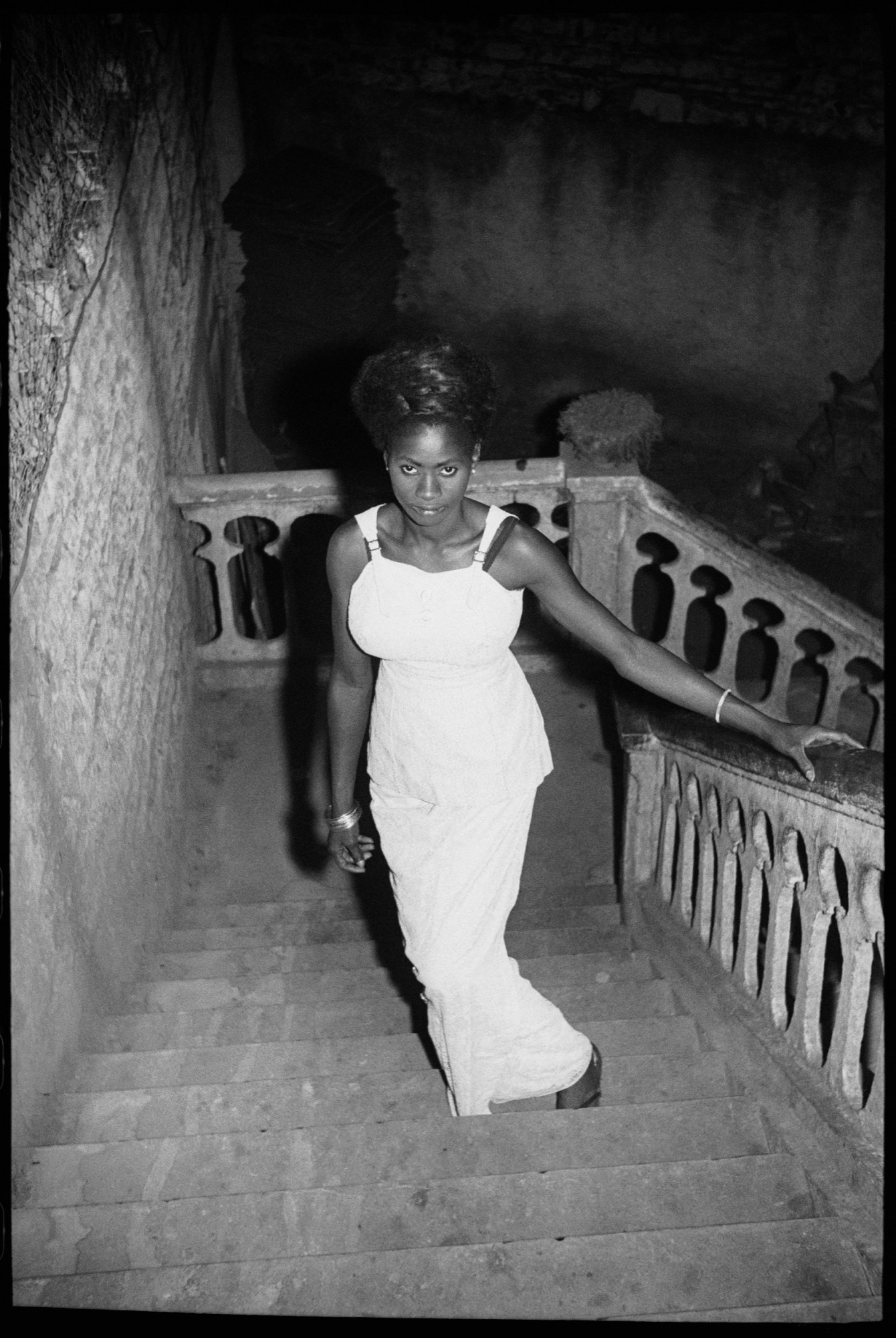

As time moves along, the images in Aunty! become more jubilant and self-crafted. There’s glamour portraits of young women in the sixties, wearing sunglasses and appearing effortlessly cool. These are the aunties we think of today: women of color who manage to thrive, even in a world that seeks to oppress them.

“Aunty! African Women in the Frame, 1870 to the Present” will be on view from Nov. 15 through Jan. 31 at United Photo Industries Gallery in Brooklyn. You can find out more information here .