This feature originally appeared in The Gallery Issue, No. 208, April 2001

Azzedine Alaïa is a giant. A small giant, but a giant none the less. At just under five feet tall, Alaïa looks like a little boy in his uniform baggy black silk trousers and Chinese slippers, his smile full of mischief. But, like they say, good things come in small packages. For this man’s influence on fashion is gigantic, his place in the design hall of fame guaranteed. Azzedine Alaïa is the Balenciaga of our times, a designer whose dedication to craftsmanship has seduced the most beautiful and the richest women in the world. For those of you ignorant to Alaïa’s genius, it is he who is the daddy of this season’s power-sex glamour, with its strapping and preoccupation with bondage. His signature is the second-skin that he creates when challenging the boundaries of flesh and fabric; his handwriting is his focus on the woman and not the clotheshorse. What’s wrong: did you think that Alaïa was a bit 80s? Well, guess what, the 80s are back. And this is Alaïa’s finest moment.

Azzedine Alaïa was born sometime in the 1940s in Tunisia. “Having tried hard, I’ve forgotten when,” he says. The son of wheat farmers, his mother’s French midwife, Madame Pinot, fed Alaïa’s instinctive creativity with copies of Vogue and lied about his age to get him into the local École des Beaux-Arts to study sculpture – a discipline in which he didn’t excel, but an education that was to be put to good use in the future. It was on his way to art school one day that Alaïa spotted a vacancy in a dressmaker’s window finishing hems for five francs apiece. He asked his sister, who was studying fashion design, to teach him to sew, and the rest is history.

Alaïa learnt quickly, patronised by two old local rich women who found him a job making copies of Parisian Haute Couture, eventually commissioning him as a dressmaker to their social circle. It wasn’t long before Alaïa was moving to Paris to work with Christian Dior, but he managed only five days of sewing lapels before he was fired due to his difficulty in securing a foreign worker’s permit. Without so much as a glimpse of Dior or his assistant, Yves Saint Laurent, Alaïa moved on to Guy Laroche where he stayed for two seasons, learning his craft and earning his keep as housekeeper to the Marquise de Mazan. In 1960, Alaïa was snapped up by the Blegiers family, and for the next five years dedicated his time to cooking, child-minding and designing clothes for the countess and her friends. It was a very special and privileged education, keeping the company of famous artists and the Parisian intellectual elite. Five years later, and with a loyal clientele behind him, Alaïa moved into his own place, and his couture-hungry clientele grew. They were onto something.

His first prêt-a-porter collection, for Charles Jourdan in the late 1970s, was not well received. That is, not until fashion editors acclaim a store in Beverly Hill’s Rodeo Drive, where gym-worked LA bodies found the perfect foil for their tanning and toning. From then on it has been worship all the way: museum retrospectives, sell-out shows, rave reviews, supermodel disciples and fashion’s recent revival of the Alaïa aesthetic. But then again, Azzedine Alaïa never really went away because he was never really part of the fashion menagerie. He never showed at the same time as other designers during the round of international collections, and never pandered to seasonal trends, choosing instead to pursue his own agenda that put him one step ahead of the rest.

Today, Alaïa’s importance as a pioneering designer and fashion visionary is indisputable. In 1991, Alaïa paid homage to Madame Alix Grès with Grecian halter-neck dresses of gathered silk; this season, countless designers pay homage to those of Alaïa. In that same year, Alaïa blew up houndstooth checks and printed them onto 50s pin-up hot pants, corseted Marilyn Monroe dresses and jean-style trousers. Question: what is this season’s biggest reference point? Answer: the 50s rockabilly sweetheart. In 1990, Alaïa championed his bandage dresses constructed from pieces of elasticated strips stitched together with the sides left open so that they wink flashes of flesh as you walk. This season’s fashion fetish? Bondage and bandage. Don’t get us wrong; we’re not accusing anyone of plagiarism, just illustrating the fact that Alaïa’s influence is as strong today as it was back then. We’re only saying he’s a giant, and that this is Alaïa’s finest moment.

Introduction Jamie Huckbody

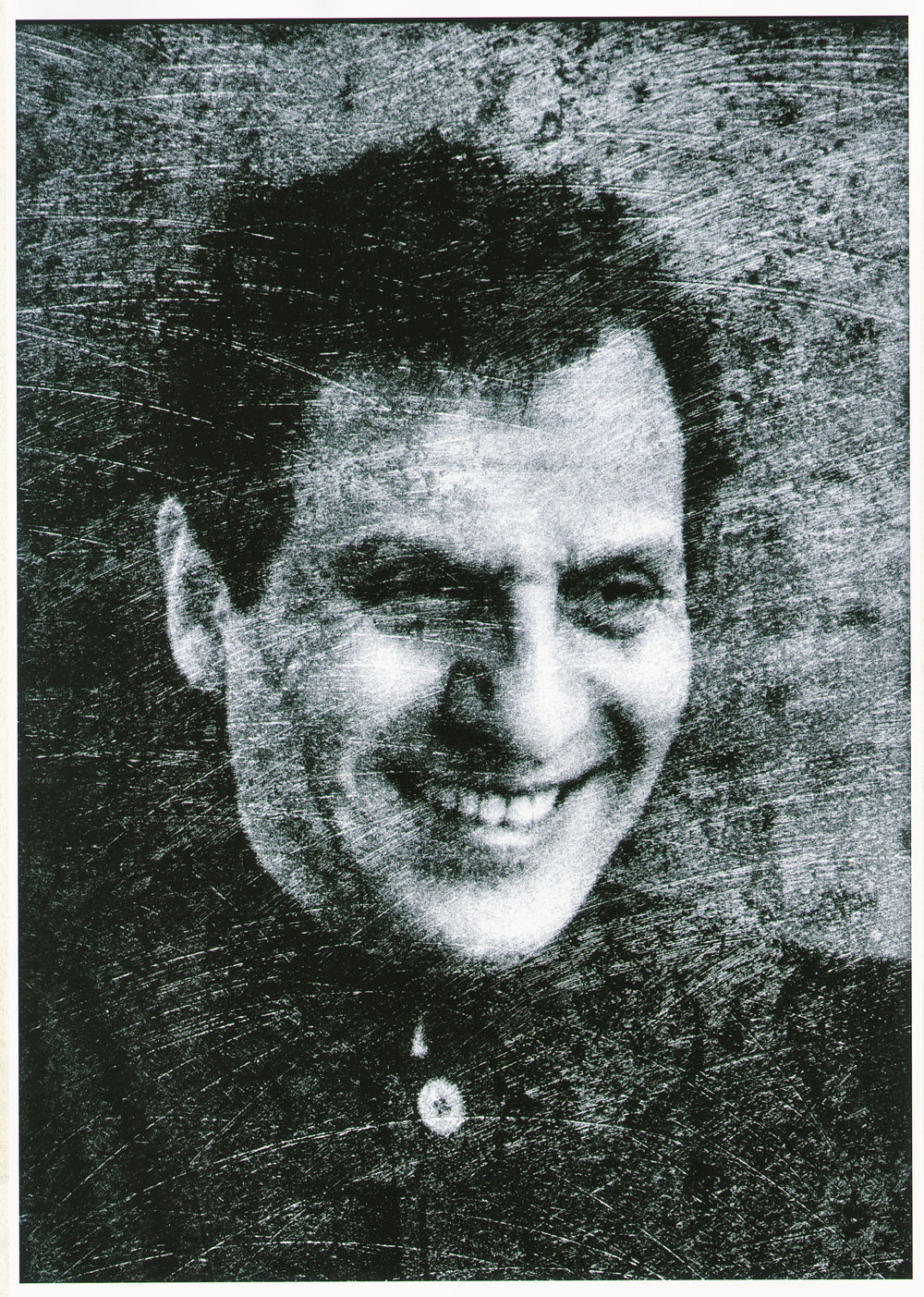

Photography Max Vadukal

Alaïa: What does Colette think of fashion now? It would be good to start with her opinion on that.

Colette: For me, it’s something eternal that will exist forever. Something that makes life beautiful, you have to see it like that. I find it fantastic to see a garment and to know that it’s really well made. It’s rare, and that’s why it’s not only a joy, it’s a privilege.

A: Passion. That’s why we get on well together – that’s the only thing we have in common. I have a lot of respect for people who do their work well. I have a lot of respect for Colette. My passion? Painting, sculpture and human beings. I create fashion because it’s my work. A lot of things really bother me about fashion these days. It’s become like a court; there are rival powers. It’s gone beyond reality. You have to be either in it or follow behind it in some way. And I don’t want to go into the whole system and conform, to adapt my way of working. Fashion moves too fast now.

C: Some things about it are certainly hard to believe…

A: Yes, it is hard to believe! Many things have been achieved already. It’s of women that we ask too much. Because a woman, after all, is a body, and journalists always want new things. Same for the models – the girls last two or three seasons then it’s over. They’re very young; it’s not good for them either. That’s why they earn a lot of money at the beginning – the career is over very quickly. Same with shops, there are very few that last.

C: What is good about fashion now is that there is something for every taste.

A: Although it’s really a luxury, it’s accessible to everyone and that’s wonderful. When you go to Colette, you can find everything from the simple to the mad – and just when you’re thinking that no one will buy it, you’ll find there is someone who wants to.

C: I always say yours are not clothes, they’re architecture.

A: That’s why there are some garments you just can’t make quickly. There’s a dress made of leather and lace and horsehair that’s not finished, even after two years. And you can’t justify the price, if you calculate how much it costs to make. I really have no notion of time. It’s a flaw, but that’s me. It’s the same for everyone who works. When I see you in your shop, you don’t even notice me. Once you were arranging the window and I was knocking away and I just laughed and laughed. It was incredible!

C: How do ideas come to you?

A: I start off with piece of leather… for me; the sketch is not the thing. You can make beautiful drawings and then the execution is completely different. Because in a drawing, the proportions are never right. I prefer working on a dummy and then a real person. That way you can see how it works.

C: How did you learn your craft?

A: I didn’t learn it at all. The profession came towards me. I started off as a sculptor at art school, although I didn’t tell my father I was there. He thought I had gone off to do secondary school, which I had begun and abandoned. Every day I had to buy paper, charcoal and paint, and since I lived with my grandfather, I couldn’t tell him – instead I’d set off with my secondary school books and pick up my stuff on the way. I needed money, and in the area was a dressmaker who wanted people to do the finishing of garments. So I’d go and see the dressmaker and tell her It was for my sister, take the garment home and sit there in bed at night with my sister sewing. It was nothing, they were just little things, but it wasn’t bad.

C: So you had a creative childhood?

A: My parents were wheat farmers, peasants. And I didn’t like the countryside; for me it was pure punishment. My grandfather used to come along in the trap and show us the fields, how high the wheat was and things like that. I used to die of boredom. But I liked my grandfather because he was completely mad. Every morning he’d settle into his colonial-style chair and all the children and cousins went up to kiss his hand. I used to refuse; saying it was dirty because they’d all kissed it. So I’d jump on his knee and kiss him on the cheek, a thing you just didn’t do then. My father was outraged. When he used to take us around the fields I was only looking at the flowers – you see, it all started very early for me!

C: How did you end up at art school?

A: One of the first things I remember is going to see the midwife in Tunisia when I was 12 or 13. She was called Madame Pinot and she received catalogues from the shops and painting books. I used to look at them and I was fascinated by painting and fashion. While she was helping women give birth – oh yes, I saw a lot of births very young! – I was next door in the dining room, flicking through catalogues from La Samaritaine [a French department store], circling what I liked. Plates, printed aprons… She used to ask me to choose clothes for her for summer and winter. I remember there were these white lace gloves and flowery dresses – I used to wear them! These are the sorts of memories that start everything off in childhood and finish by pointing you towards your profession. It was the midwife who signed me up for art school. I wasn’t even 16 yet and you had to be 16. She knew the director and told him she had brought me into the world, and since in Tunisia people write dates any old how, she told him I was 16 and a half, even 17 years old. So I aged two years on the art school entry form! I went to the classes and learnt to sew by watching my sister, who was at college, a convent in fact, and I used to do her embroidery for her with different coloured threads for the different parts of the picture. That’s how the painting and the fashion got started.

C: Do you remember the first time you did a fitting?

A: A skirt… it was for a friend from art school, my best friend. She was beautiful and skinny as anything. We went to the souk and bought this material. I had seen in the Dior catalogues that their skirts were tight, with the pleat behind. So I told her, right, we’re going to make you one, and we made it tighter and tighter so that in the end she couldn’t get out of it! She had on one of those little stripy Tunisian jumpers, which we made again for this season’s collection. The skirt was so tight she could hardly move. We kept saying it was much prettier that way. We had to get on the tram in Tunis but she couldn’t manage it. We pushed her from behind and it was a real spectacle.

C: So you always made clothes for seduction!

A: Of course! What else are clothes made for? A woman’s not going to buy a little skirt for a lot of money if it’s not for seduction – I mean, what’s the point?

C: Do you design for a particular woman now?

A: No, no favourite women at all. You can’t love one in particular. You have different affections for different women… it’s hard. I don’t work for one woman, but women in general.

C: Your clothes are very much about restriction, a fascination with bondage. Where does that come from?

A: It comes from Egyptian mummies.

C: That idea of bondage has inspired many designers this season. How does that make you feel?

A: We are always inspired by something. I continue my work as I always have done. Everyone does it in their own way, adds their own touch.

C: Does art inspire you?

A: A lot, thank God. But I’m not inspired by it in my work really. I just carry on working and the work progresses, I do one thing or another, and you carry on as normal.

C: Much of your work is displayed in museums.

A: The Musee des Beaux Arts in Paris, in Marseilles, New York… not in Tunisia. I might donate some clothes there later on. When I see beautiful clothes made by Dior or Vionnet I want to keep them, preserve them. They represent an era. Clothes, like architecture and art, reflect an era.

C: Do you like galleries?

A: It all depends on what’s showing. I can’t say I like this gallery or that. When I go to New York I do all the galleries.

C: Your work was exhibited in New York recently as part of a major retrospective at the SoHo Guggenheim. Were you happy with that?

A: It would be really ungrateful if I wasn’t happy with that! People would have said ‘What a cretin!’ I was delighted.

C: The presentation was interesting – all your dresses displayed in front of Andy Warhol’s Last Supper paintings.

A: It’s dangerous to mix Andy Warhol and a dress, but it turned out well.

C: Did you know Andy Warhol? Is that why they chose to show your designs like that?

A: He was very funny. One time he had invited me to this office, like he often did at lunchtime, and there was this big table with everyone he worked with around it and he introduced me to them. Then this trolley comes along and on it lots of brown paper bags, like doggy bags, which he hands out to everyone – everyone’s sitting there with this bag on their knee, and in each one there’s Coca Cola and a sandwich. Then after you’d eaten, the bin would be wheeled past and you’d drop your litter inside. I found that the height of chic! He’d do the same thing each time I went, and then he’d show me what he was working on.

C: Did you have funny times with Warhol?

A: Yes, especially at night because he always went out with his camera. He had his lock of hair that fell over his face and he was always rearranging it. And he was funny, very funny. Despite the fact that I don’t speak English! He used to take me into a corner and speak to me in English, and I’d reply in French, and we each told our own story. I’d say what I could see, how I was having a great evening, although I had no idea what he was saying…

C: A final question, as we have been talking about your memories of Warhol. How would you like to be remembered?

A: Whatever people want to think! As a naughty little boy! He likes dogs, he has cats… I’m like the nomads – I’m only passing by. When I pass through a place, that’s it. I take everything with me. Work is different – it’s not intimate. I don’t have things to hide. I’m secretive about some things, but I am recognised by my work. How can people be interested in the fact that I sleep on a canopy bed or that I share a mattress with my dogs, or that I change my vests three times a day because the dogs make them dirty? If I’m judged in those terms then it’s a disaster! I have done some very interesting things; I never regret anything. I just want to be loved…