When I get hold of Emma Cousin, she’s sitting in the front room of 52 Whitbread Road. The room is totally bare aside from Emma herself, fresh through the door after a twelve-hour stint at her studio. There’s lots more work to do.

Emma is one of three women behind Bread and Jam, a series of experimental exhibitions hosted in a refurb-ready house in Brockley, deep in the heart of south east London. This edition, titled The Shapes We’re In — started with just two stipulations: each artist had to be female, and had to work with a specific, mundane shape: a heart, a flower, a slice of toast. That aside, the artists were given carte blanche: ten whitewashed rooms to fill with eleven shapes. They were encouraged to work with new media, making art they wouldn’t have the chance (or money, or space) to display elsewhere.

“It’s something of a test,” Emma suggests. “Either an artist proposes something they want to make, but have never had the chance to, or displays something they’ve made and never shown. Or they tell us they want to make something and they don’t know what’s going to happen.”

Many of the artists on show are focussed on change. Considering the makeshift gallery’s setting, that’s hardly a surprise. 52 Whitbread Road has been in the same family since it was built in 1895. When the house finally came on the market, Cousin bought the property, and along with Emily Austin and Rebecca Glover, set about creating a distinct exhibition space to be used for free by her favourite artists. “I saw it as an opportunity to put on a risky, fun and curious exhibition that connected artists to one another, artworks to the public and a show to a domestic setting”, explains Emma.

The house was meant to be used only once, but tonight’s show is the third to be held here, and another three are in the works. Emma describes 52 Whitbread Road itself as the “fabric” of the exhibition, and the house is as much part of the experience as the art it contains. On the top floor, two-tone floorboards are flecked with paint and scribbled over with circuit diagrams. Wires snake between the planks, and the stucco on the walls is cracking. The bareness of the house makes the art more striking – in turn, the beauty of the art makes it impossible to ignore the setting’s impermanence.

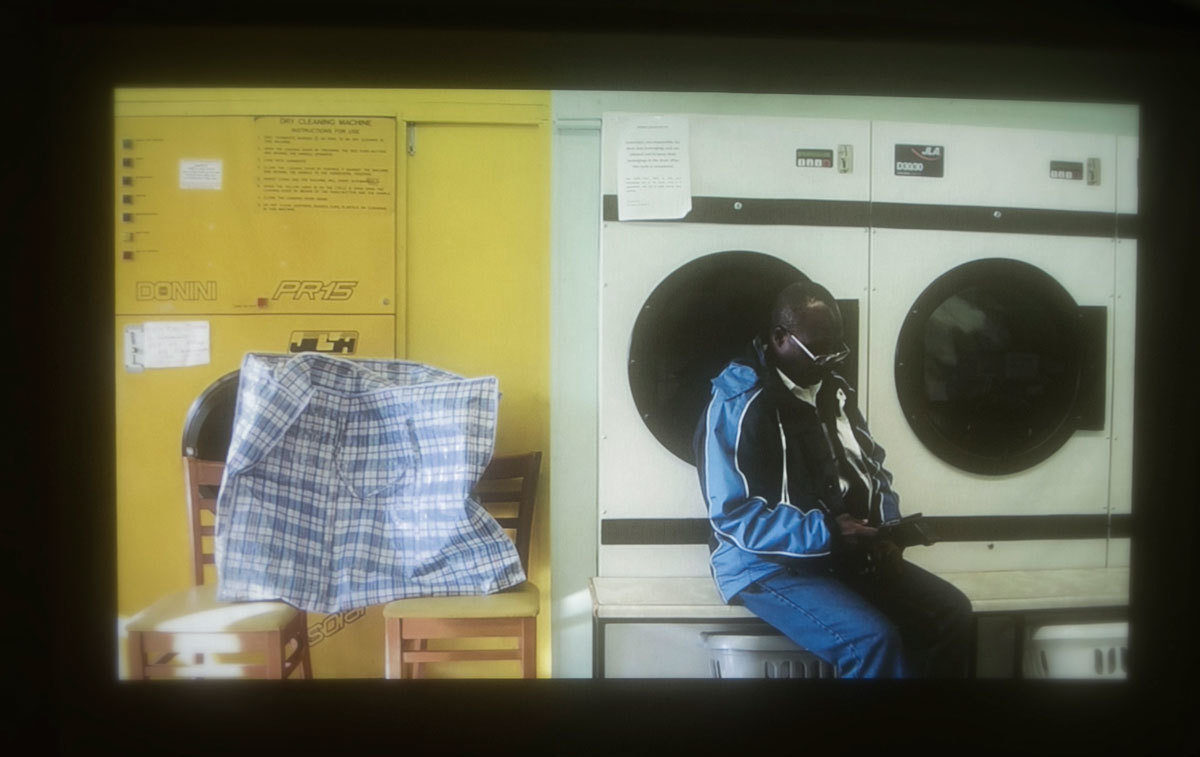

On that barren top floor sits the standout piece: Claire Macdonald’s film Launderette. Ten men are filmed, alone, at launderettes in East London. Each discusses his innermost secrets – a work-induced nervous breakdown, youth lost at a foster home, a man’s disappointment at fathering only daughters. Macdonald’s wonderful documentary instinct is matched by the earnestness of her cinematography. These testimonies are intercut with gorgeous shots of tumbling laundry, in one particularly memorable frame, wet clothes cut circles into the condensation inside a washing machine.

Launderette is notably the only piece at Bread and Jam with any masculine presence (aside from Frances Richardson’s raucous, time-lapsed penis-sculpture video, The Making of a Gentleman) and each of the men it features is compromised in some way. When I watch Launderette, the press releases schtick about “reimagined domestic spaces” doesn’t sound corny or hollow at all. The air of take-no-shit femininity permeates every room, and Macdonald’s frank look at modern manhood sets it off perfectly.

Emma Cousin’s paintings are at the centre of the house, hanging from the ceiling and walls of the first-floor hallway. Each is around a foot square, with a beating organ, slightly bigger than life-size, painted in oil at its middle. Emma’s palette is reminiscent of Bacon; her hearts are in deep shades of red, her backgrounds in warm pink.

“If you’re a representational painter there’s a struggle”, Emma explains, of her work, that sit in the centre of the house. Each painting is around a foot square in size, with a beating heart painted in oil in deep shades of red on warm pink backgrounds. Mostly playful, with hearts made to look like pincushions, comic strip tiles or hand-grenades – but Heart On Your Sleeve is something else. The shadowy, titular heart – balancing delicately on a white sleeve – is too realistic to laugh at. It presents its physicality immediately; the play on words is relegated. But slowly, you connect the heart of the cliché with the heart of the body; you’re forced to break down the meaning of the phrase to its constituent elements. The heart of metaphor becomes irrepressibly real.

“You don’t just want to illustrate,” she continues. “You want to get away from literal representation. We expect our hearts to run, dance, keep fit, deal with salt, fall in love, get broken – a little heart doing twenty things at once is hilarious, but I want people to look at a painting and feel a sadness or vulnerability.”

That combination of humour and pathos is clear, not only in Emma’s pieces, but throughout the house. These paintings, sculptures and videos are beautiful and delicate; but they’ll outlive the walls they’re resting on. 52 Whitbread Road has barely changed in one hundred and twenty years, but in a few weeks it’ll be gutted beyond recognition; the art it holds will still exist.

Emma’s house gives artists time and space to display their work – but it’s one of the few venues in the area that’s doing so. As property prices creep up, practising art in south London is getting harder. Tonight’s exhibitors all balance day jobs with the everyday work of being an artist. With rising rents forcing them further from the centre of the city, this balancing act becomes ever more difficult.

“The main problem for artists”, says Emma,”is working out how to make art in a capitalist society. If you have to travel an hour to your studio after an eight-hour day at work how much energy do you have to make great work?”

“My studio is in Deptford, and I have to move out in May. That makes it much harder – and it’s not just me, it’s a huge number of artists. It’s changing massively. Studios owned by the council have closed down, and they made the area saleable to practising artists. It’s a bit short-sighted to push us out completely just for the benefit of gentrified society.”

It’s hard to imagine a more elegant protest against gentrification than Bread and Jam. The work here is so totally engrained in the fabric of the house and in the spirit of the area – it could never be so effective as it is in this exact place.

Credits

Text Mischa Frankl-Duval

Photography Matthew Harms