Detroit, apparently, is rising from the ashes of a generation spent in decline. A once grand monument to American exceptionalism, industry and strength (as well as leaving an indelible mark on popular culture through Iggy Pop, The White Stripes and techno), the city was left to rot as the car factories that earned it the nickname Motor City, moved out, to be replace by empty lots; the population dwindled, funding was cut, and eventually the city went bankrupt.

We’re all familiar with the ruin porn images of the grand gilded age facades that were left to turn into urban jungle, the trees taking root on the old factory floors and only the absence of packs of rampaging wild animals separated it from Jumanji in the popular imagination.

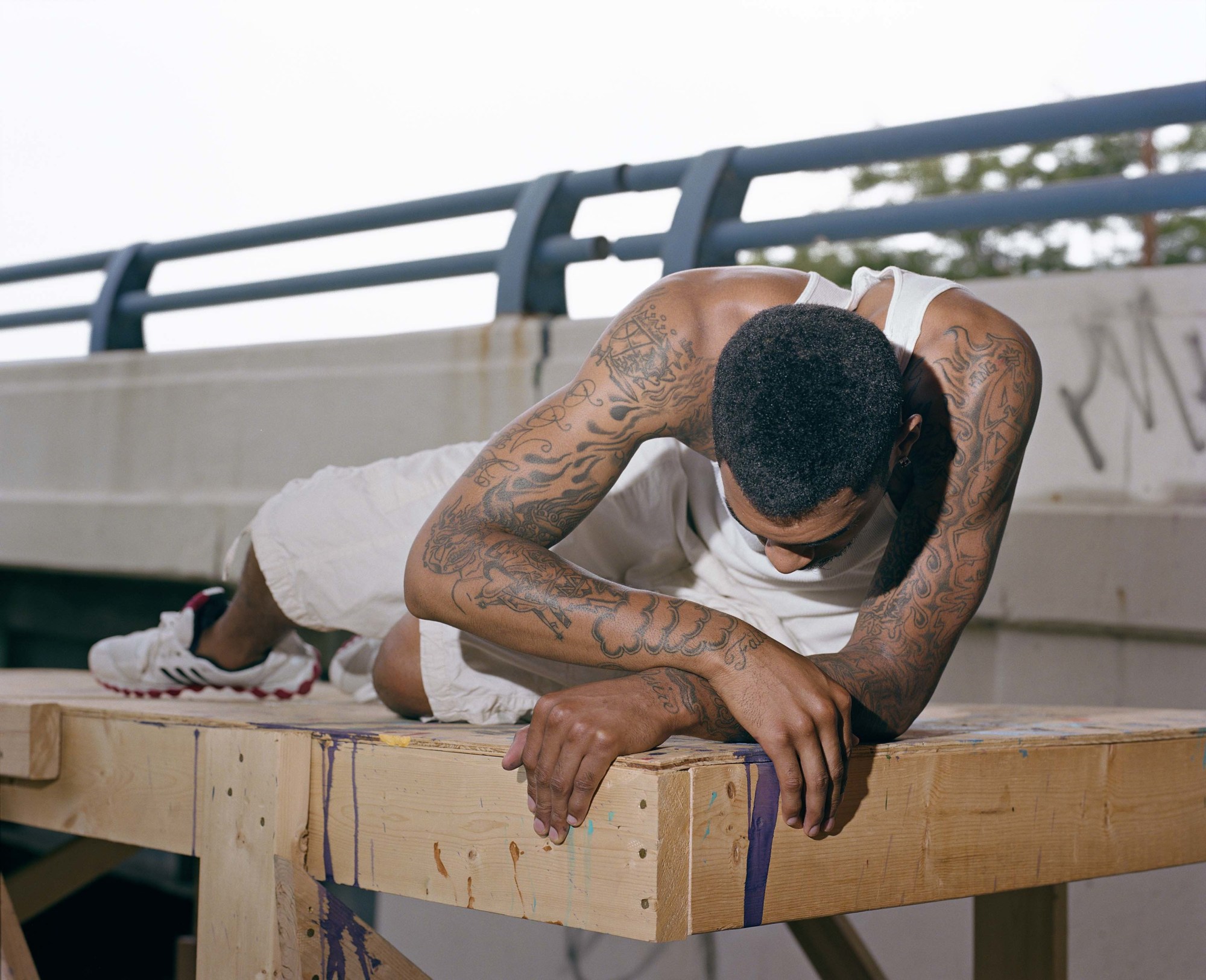

Two photographers – JW Fisher and JT Leonard – spent five years in the Rust Belt cities of Detroit, Toledo, and Pontiac, trying to find a new way of looking at America’s industrial decline and the landscapes it’s left behind. Their book, Landmark, moves beyond the sensational depictions we’re used to in order to find a more nuanced and contemplative visual document of the once-beating heart of American capitalism.

What was the inspiration for the book?

We had begun working in and around Detroit in 2009, and when we arrived on that first trip to Pontiac, we knew the work would utilise the “rust belt” as a backdrop, but we also knew that we weren’t interested in lamenting the urban decay. At the time we felt that we were looking to identify a “stray” cultural by-product. Something not wrapped up in the malaise.

Why specifically the rust belt? What attracted you to this post-industrial area of the USA?

Well, we ended up in the rust belt by accident, at the suggesting of a former mentor. We found ourselves living in an abandoned and homely art gallery in Pontiac, Michigan, making work every hour of every day.

Early on we decided no matter where we ended up, that we would say yes to everything while working together. This approach allowed us to have an exchange with the people we came into contact with. Chance encounters shaped the work and our understanding of these areas. We often would shoot jobs for our subjects in exchange for footage or a picture we wanted to make. Many of our subjects that we came into contact with were looking to define, or sometimes redefine, their own individual identity. After that initial trip to Pontiac, we would come together in Detroit or Pontiac or Toledo to work for a few weeks each year.

We were well aware of some of the photographic work coming out of these areas over the last few years, and had no interest in repeating an aesthetic of decay. We wanted to attempt to react and contribute to the dialogue of these cities in a different way; one in which we could attempt to reflect a sense of hope or represent an idea through a sort of photographic metaphor.

The book speaks of a disillusionment with conventional documentary images, what do you feel Landmark reveals, that they can’t?

In addition to being aware of some of the work of our contemporaries who have recently flocked to the “rust belt” to arrive at pictures that are hauntingly beautiful in a representation of a dubious fate, our intentions were very different, but of the same tools, and perhaps language. We wanted to dismantle our own conventions of documentary practice, to constantly question the camera’s ability to represent the facts.A lot of people can observe things, and photography makes it seem credible. There was never a preliminary notion that what we were doing would ever need to move beyond the act at that moment.

What is your opinion on the usefulness of “ruin porn” in conveying the post-industrial decay of cities like Detroit?

Ruin porn was not our interest or specialty. We didn’t want to enter the “ruin porn” working method. The post-industrial decay of the area was and is remarkable, yet we knew we couldn’t make that work, and at the same time as we believed that often art at its best reflects culture and society at a given moment, we knew that we couldn’t or shouldn’t avoid the conversations and much of the photographic work coming out of these areas. So a problem of how do we contribute and comment was apparent early on. So ruin porn’s usefulness was such that we wanted to seek a different conversation, one that was more about space, and working within communities and with people, as well as transformation through our own interventions in the landscape.

What is the importance of showing the human figure in the images, of putting the post-industrial city into context?

Just that, context.Photography often can perfect isolation or dislocation through the removal of figure. For better or worse, we found that we had come to expect that in many post-industrial city photographs the figure is removed. At times in our pictures the figure drove the idea, and in other cases bodies were among the many-pictured elements. Our truth was one in which early on our contact with people was of the utmost importance. So to contextualise our work we knew that people would enter the project in front and behind the camera.

What role do humour and the surreal play in the work?

Humour definitely is a large part of working through the ideas, but we aren’t sure how much of that is visible in the work. In choosing the title Landmark, we were interested in a relationship between allusion and metaphor. When we first were in Pontiac we met a gentleman who told us he knew we were coming–not that someone had told him, but rather he sensed two photographers were coming from New York to help him make a film about a peppermint farm. Nonetheless he wasn’t surprised to see us and had tasks lined up for us. As we got to know him better we learned of his involvement with Landmark Education, which is a self-help seminar program that aims to help people self-realise their own potential. We thought of the word “landmark,” as a beautiful metaphor for so much and so many that we had come in contact with. There was this sense of hope and potential, which we aimed to convey in the work, but once again the fate of the landscape was dubious and those we came into contact with very uncertain.

What about the text that intersperses the imagery?

Text can often be a challenging variable when paired with photographs. Pictures and words can age, or date themselves and one another in different ways. Specifically our decision to work with the “Chaptering” text that Lisa Larson Walker provided was in an effort to divide, and unite the work in contextual ways. Lisa saw the work develop over the last couple of years and was involved in our discussions surrounding the collaborative practice through lectures, and panel discussions. One of the things we all wanted to accomplish within the text (perhaps as with the photographs) was use of abrupt and jilted phrasing–such as language layered within the landscape, signage, directions, advertisements, etc.–where thresholds vary from a high density area to a lower density area and remain even in spaces of “abandonment.” Rather than feature the text phrases as a conditional sentiment, we allowed the efficacy of a word to create a space of its own through those pages.

What did you intend for the book to achieve, politically or aesthetically?

Our original aesthetic focus was to break down our individual practices, for ourselves. We were after a craft that embraced and celebrated our very different ideas and occupations into a new discovery. At its simplest, collaboration may mean dichotomous examples of individualised thought, or work that very much becomes a play of authorship. As we have seen the consequences of modernity challenge this landscape, these post-industrial cities, and many of the communities residing in the areas we chose to work within, we felt the need to challenge our modernist inclinations by disrupting our individualised and centralised practices. The decentralisation in Landmark is essential to its meaning.

How does this matriculate into a political concern? Communities, cultures, neighbourhoods, relationships, these are often times binary, and ultimatum negotiations. It is either good, or it is not. It functions, or it is dysfunctional. In the case of a post-industrial city one can suggest razing the city and planting a garden. We wish it were that simple, but it never is. What does this book achieve politically……you tell us?

Landmark by J.W. Fisher and J.T. Leonard is published by Daylight Books. daylightbooks.org/landmark

Credits

Text Felix Petty

Photography © J.W. Fisher J.T. Leonard.