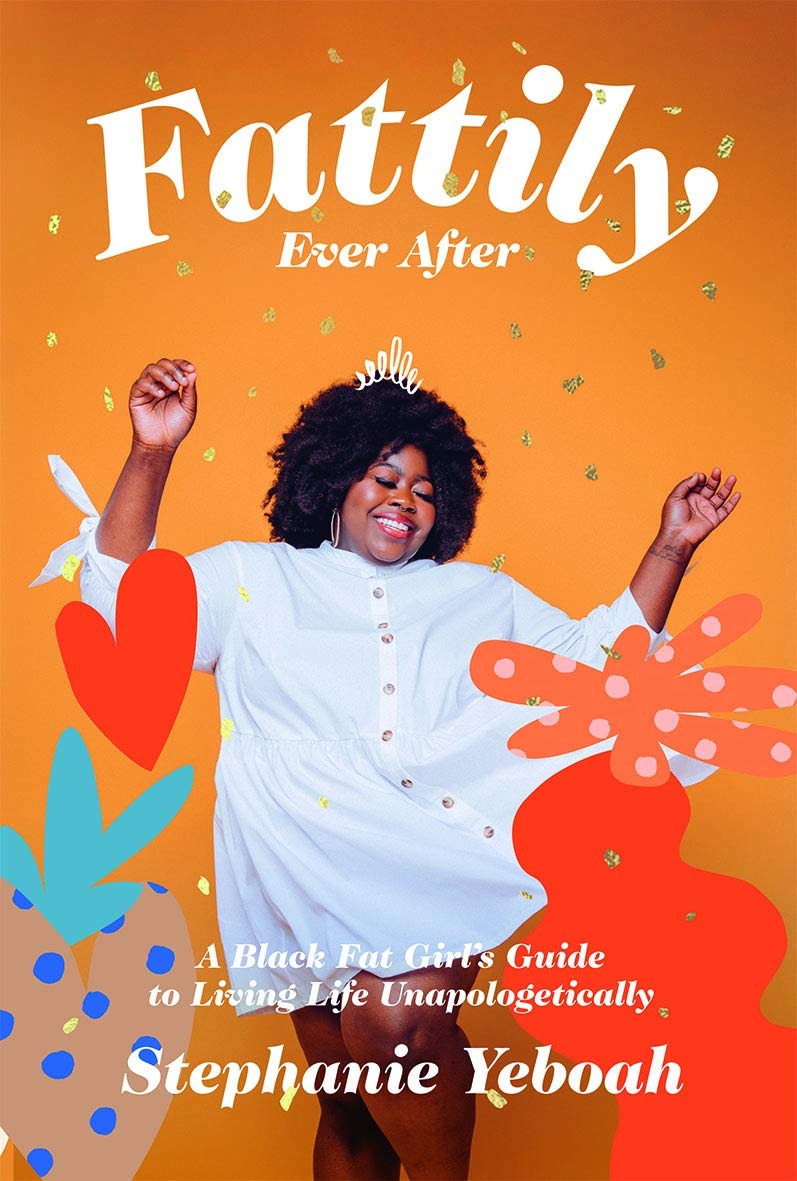

For too long, Black, plus-size women have been bullied, objectified and humiliated by society, whilst being portrayed as caricatures or stereotypes in mainstream pop culture. But with icons like Lizzo bringing global attention to the fat acceptance movement, things are slowly changing. Stephanie Yeboah’s debut book, Fattily Ever After, is an exploration of what it’s really like to navigate life as a fat, Black woman – plus inspire others to find self-worth and confidence through her insightful tips and honest advice. The following is an extract from that book.

Eating disorders look different on Black women and the conversation is wildly different when it comes to us. Period. 100% of the programs I’ve ever seen on TV about eating disorders have all been about white women. I can’t recall one single story where the subject was anorexia and a Black person was included.

Normally, when we think about eating disorders, we picture a slim white womxn with a visible rib cage and a gaunt face. Even when it comes to mental health and eating disorders, white womxn are still the standard. This is partly the reason why so many Black womxn find it difficult to come forward about eating disorders – that, and the fact that sometimes, being from an Afro-Caribbean or African American culture sometimes doesn’t provide the safe atmosphere one would need and hope for, in order to share something so vulnerable and personal.

Black teenagers are 50% times more likely than white teenagers to exhibit bulimic behaviour, such as binging and purging. People of colour with self-acknowledged eating and weight concerns were significantly less likely than white participants to have been asked by a doctor about eating disorder symptoms, despite similar rates of eating disorder symptoms across ethnic groups. When presented with identical case studies demonstrating disordered eating symptoms in white, Hispanic, and Black womxn, clinicians were asked to identify if the womxn’s eating behaviour was problematic; 44% identified the white womxn’s behaviour compared to only 17% for the Black womxn. The clinicians were also less likely to recommend that the Black womxn should receive professional help.

There can be a couple of explanations for this. Eating disorders in Black womxn and womxn of colour may be, in part, a response to environmental stress (i.e., abuse, racism, poverty). Therefore, given the multiple traumas that we can be exposed to, we may be more vulnerable to eating disorders than our white counterparts. The third statistic is the one that really troubled me, to be honest. There has long been this myth within the healthcare industry that Black womxn are physically ‘stronger’ and more equipped to handle pain than our white counterparts. This also goes for mental/emotional issues too. Therefore, because of this, we aren’t given the same level or duty of care as white womxn. We’ve recently heard statistics being thrown about this year that back up this theory, such as Black womxn in the UK being five times more likely to die in childbirth than white womxn due to lack of care and racial microaggressions, and the same can be said for how we deal with emotional trauma too.

I know so many Black girls who have struggled with this in some way, shape or form, and even their mothers before them, who may then project these ideologies and habits onto them. Yet we are casually omitted from larger mainstream conversations about eating disorders, mostly because our purported ‘strength’ dictates that we should be immune to ‘weak’ diseases like eating disorders. That suffering from an eating disorder is a ‘white girl’ illness. And that any discomfort we display with food or our bodies is a personal failing rather than a tragic display of a world that hates our bodies yet takes what it wants from us, time and time again.

In 2017, a study conducted on college campuses in the United States found clear discriminatory practices among health professionals when acknowledging, diagnosing and treating eating disorders in young Black womxn versus their white counterparts. Obviously influenced by the stereotype of the ‘strong Black womxn’, doctors in the study appeared not to believe that Black womxn were susceptible to disordered eating. Stories like these, together with the general distrust of medical professionals that many Black people feel, can discourage Black people with eating disorders from seeking help.

For me, I never really sought help for what I was going through, as in my mind, I thought it was what I deserved. My punishment for being so fat. Punishment for not looking the way ‘normal’ Black womxn are ‘supposed’ to look. I obviously couldn’t tell my family either, because I assumed that they would either ignore it, or laugh it off. I felt like from their point of view, it would be absurd to claim to have an eating disorder because of all the hungry people back home in Ghana who weren’t afforded the privilege to have free access to food like I was. There was an inherent cultural shame knowing that I came from a country positioned in a ‘third world’ continent and yet I was choosing to not eat food, while people starved. It taught me that even in the midst of our mental health struggles, Black womxn are not allowed to be fragile. So, we are left with the suppressing choices of being a ‘cautionary tale’, or a shining ‘role model’ of morality. None of these choices allow us to experience the full range of living in our truth, which should include the right to be fragile.

In a perfect world, fragility stemming from eating disorders would be met with compassion and empathy, and it would be if I (and other plus-size Black womxn like myself) were ‘fragile’, white girls. People, as well as medical professionals, would attempt to hold space for us and what could potentially be a cry for help. As fat womxn and fat, Black womxn, we should be able to be afforded the same luxury as our white counterparts, and be offered help, patience and support as, and when we need it. We cannot – as a society – continue to have a healthcare service that bases its diagnoses and optional duties of care on assumptions about bodies rooted in racial microaggressions and fatphobia, at the expense of disadvantaged people – it’s killing us, literally.

Fattily Ever After, by Stephanie Yeboah, is available now.