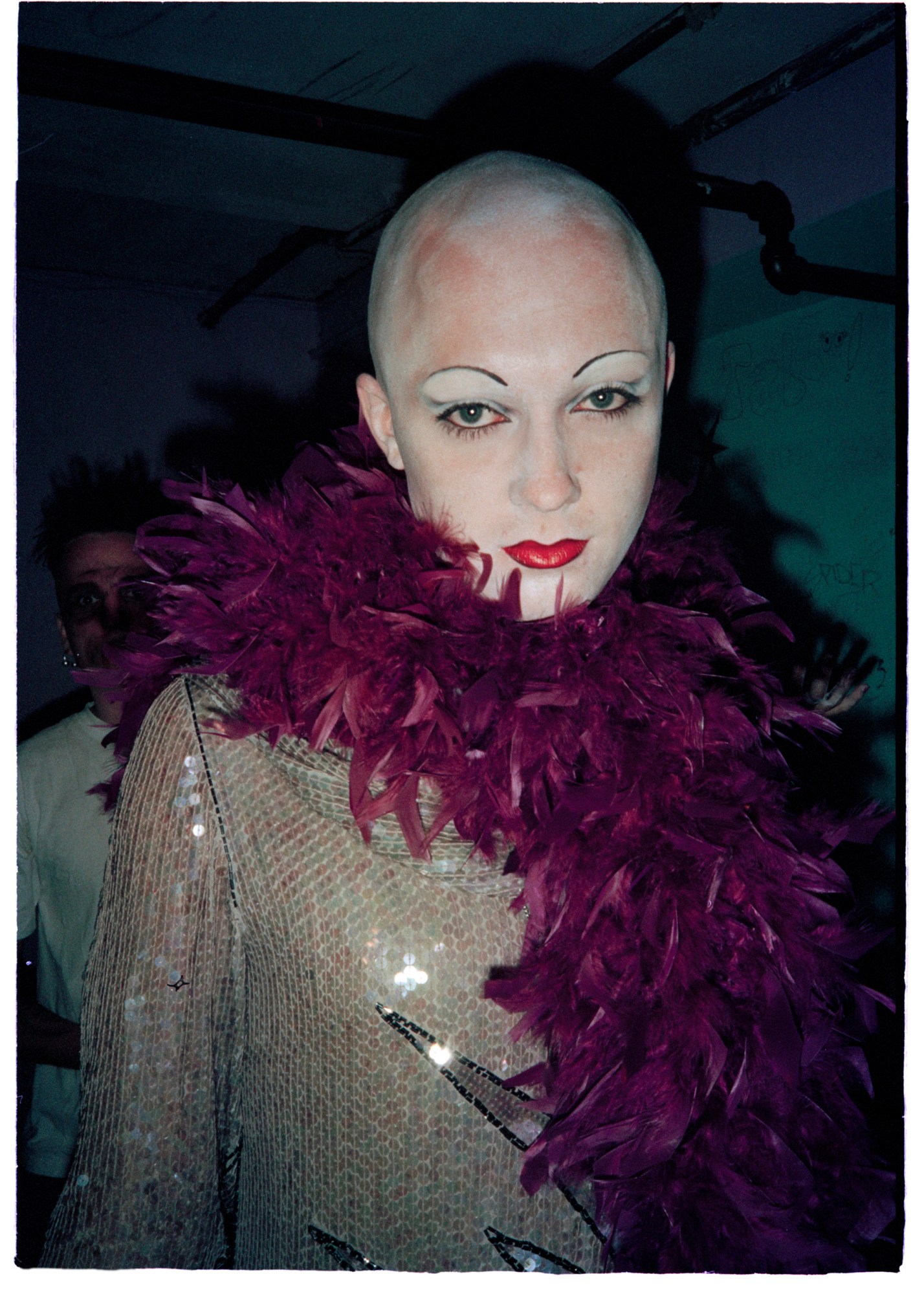

If you attended Wigstock — the long gone annual drag festival in New York’s East Village — in 1992, amid the heaving crowds and big, bright drag queens, you might have crossed paths with a much more confrontational figure. Shunning the rainbow party vibe, the performer Anohni stalked Tompkins Square Park in a barbed wire halo and a homemade T-shirt that acerbically proclaimed ‘My Cock Is Riddled with Maggots’. She was handing out fliers — for what exactly, it was unclear — with “a drawing of a transsexual mutant with bulletproof tits screaming ‘I Will Murder You’,” plus the date and time of something called Blacklips.

After passing out thousands of these fliers to revellers, Anohni and her friend and collaborator Johanna Constantine were surprised to find that absolutely no one turned up to their Monday night, 1am punk drag happening. “We thought it would be a hit,” Anohni deadpans in Blacklips: Her Life and Her Many, Many Deaths, an upcoming book charting the anarchic underground world of the experimental performance night that, after an admittedly inauspicious start, ran every week for three years at the legendary queer nightlife venue, the Pyramid Club.

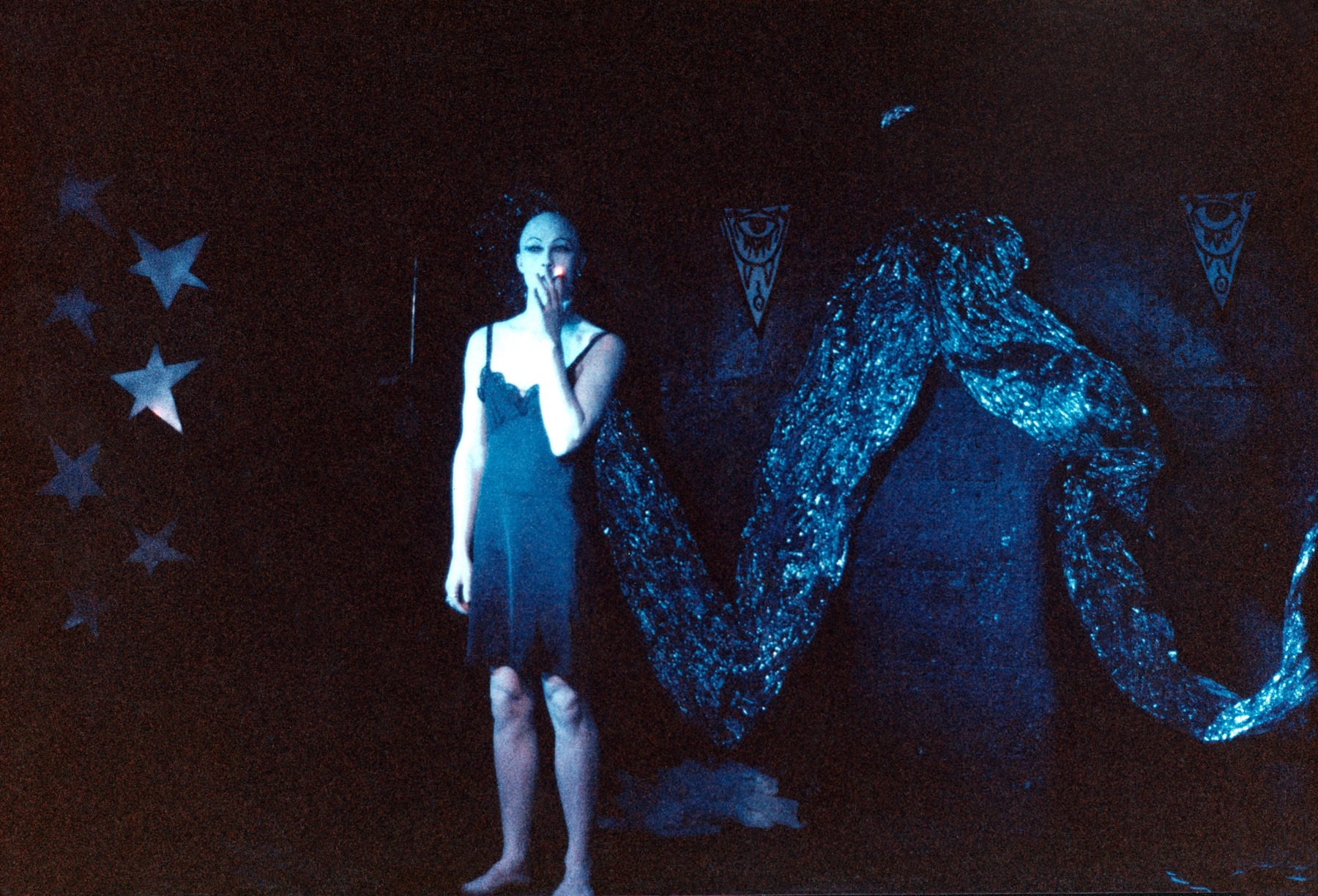

On that night with no audience, Anohni and her collaborator The Psychotic Eve decided to deliver their performances all the same, setting the precedent for an event that pandered to no one, characterised by defiance and a dedication to beauty set on their own resolutely queer terms. Anohni also remembers it as the first night she performed “Rapture”, a devastatingly powerful incantation that eventually found a worldwide audience via her band’s self-titled debut album, Antony and the Johnsons.

Inspired by the ethos of film and performance art pioneer Jack Smith, the founding members of Blacklips worked with what they had, taking trash no one else wanted: from the actual garbage off the street they used to make stage sets, to the undesirable Monday night slot at the Pyramid Club. Anohni, Johanna and Psychotic Eve wanted to create a brasher alternative to the entertainment-focused cabaret found at other queer club nights like Jackie 60, one that spoke to the reality of violence, demonisation and death that surrounded them during the AIDS crisis.

“Blacklips was a reaction to the presence of the Christian far right ‘Moral Majority’ and the influence that it was having on our lives,” Anohni tells i-D. “There was a real war being waged. A violence directed towards the queer community and the arts community by the fundamentalists that had taken hold of America during the 80s through televangelism. A new momentum of loathing that sought to weaponise AIDS and abortion as issues that could capture the public’s imagination. By the early 90s, we were pretty sick of it and really hissing at the dominant culture in the United States.”

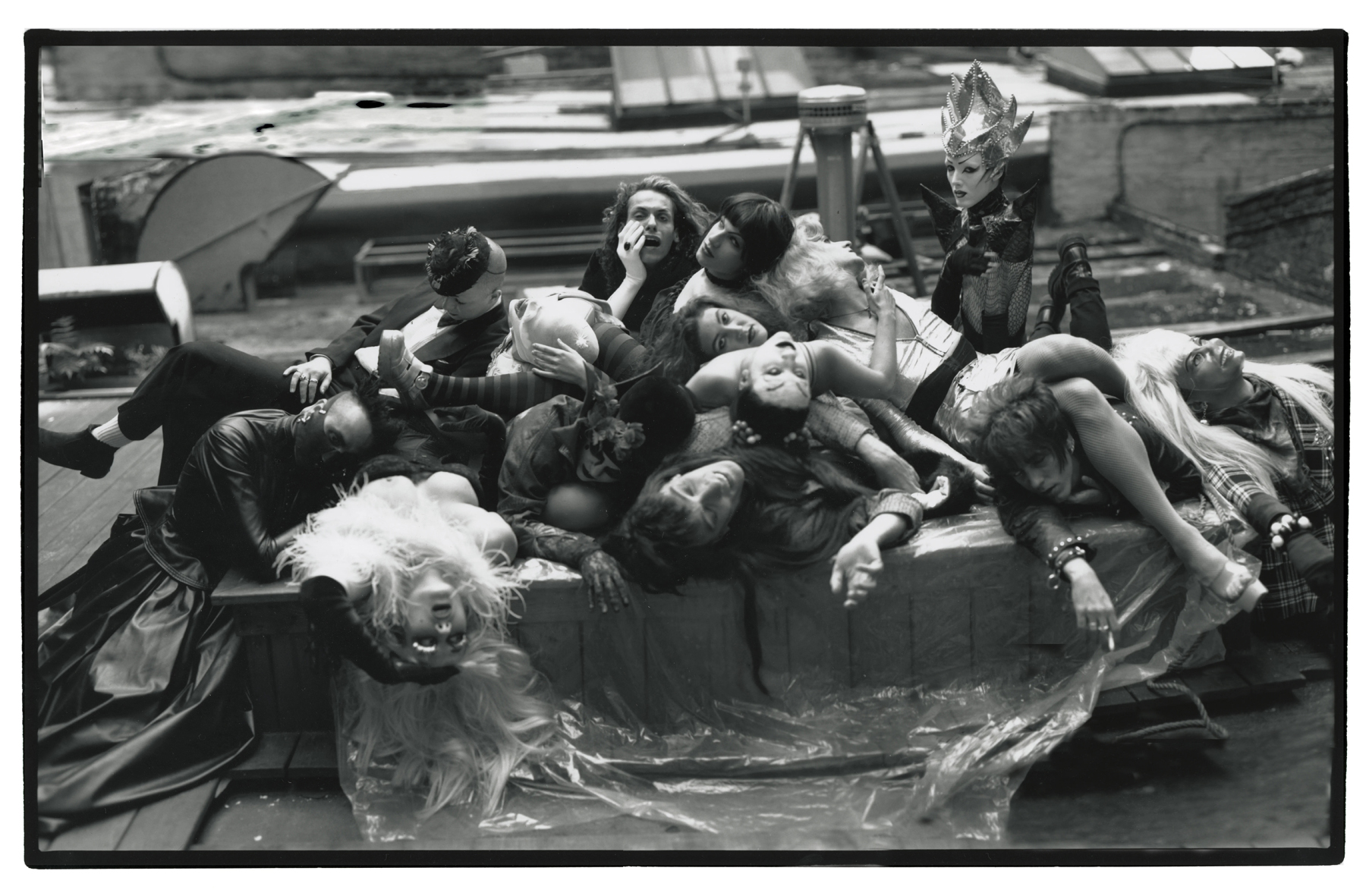

Before the internet, young creatives seeking community had to physically go out on the street to find other like-minded people. Anohni’s alarming T-shirt and bizarre fliers — with their fevered slogans, ‘Defy god’s natural plan’, ‘Be beautiful, worship the devil’, ‘Annihilate gender’ — were fine-tuned to attract rare and precious kindred spirits, while repulsing and repelling everyone else. It worked. Their collective filled up with a cast of imaginatively named performers including Sissy Fitt, Kabuki Starshine, Lily of the Valley, Ebony Jet and Lost Forever (aka Marti Wilkerson, co-author of the Blacklips book.)

Blacklips’ aesthetic was spitting and hissing with rage, but the night was also fuelled by an unusually serious dedication to original art. The group staged plays that ran from 45 minutes to two hours — some twisted takes on classic tales like Jack The Ripper, where the sex workers took their revenge; others, speculative worlds of their own invention — all interspersed with ‘numbers’. But as Marti explains, these weren’t your typical cabaret tunes. “There was a maggots’ ballet!” she recalls. “Psychotic Eve was dancing as a human-sized maggot, laying eggs — we were using Tic Tacs as the eggs — and I don’t even think anybody was singing. Just dancing. Expressing their maggoty-ness.”

At other times, numbers could transcend the main feature. “I remember one really crappy play that was just painful,” Marti says, “and Sissy came on and sang a version of ‘Imagine’ wearing these big silver eyelashes and people were just rapt.” Anohni performed her own hauntingly beautiful ballads. “My goal was to make everyone who was drunk or on Special K in the club cry in three minutes,” she says. “To see if I could get them to have a really intense emotional experience that sort of disoriented them, in an environment where you’re not supposed to have anything but cynical or guarded expressions of emotion. Other clubs didn’t like it at all, what we were doing at Blacklips. It was too anarchic. But for the people who were attracted to it, it gave us space to breathe.”

Anonhi views the level of commitment in Blacklips performances as “creativity as a survival strategy.” It’s why they started describing themselves as a performance ‘cult’ rather than troupe, following news reports from the deadly siege on a religious cult in Waco in 1993. “‘Cult’ now is not that meaningful, but in those days it was still a word that posed or suggested a threat,” she explains. She credits Rozz Williams, of 90s LA death rock band Christian Death, and Diamanda Galás, the avant-garde singer and outspoken AIDS activist, as inspirational examples of “underdogs or marginalised people or creatures that utilise ingenious strategies to scare their perpetrator away.”

“That was a Blacklips strategy, a certain kind of reverse camp,” Anohni says. “You need to have the experience [of marginalisation] to move through the firewall of defences to get to the inner circle of buoyant creativity. It’s guarded with sharp teeth around the edges, but the teeth are an illusion. It’s not really a cult, it’s actually people trying to work out what’s happening, and what’s happened to them, what this culture is that they’re a part of; trying to have a good time and also make sense of the madness of things.”

Blacklips: Her Life and Her Many, Many Deaths is out 14 March 2023 published by Anthology Editions. The companion compilation, Blacklips Bar: Androgyns and Deviants — Industrial Romance for Bruised and Battered Angels, 1992–1995, is out 10 March.

Credits

All photography courtesy of the artists.