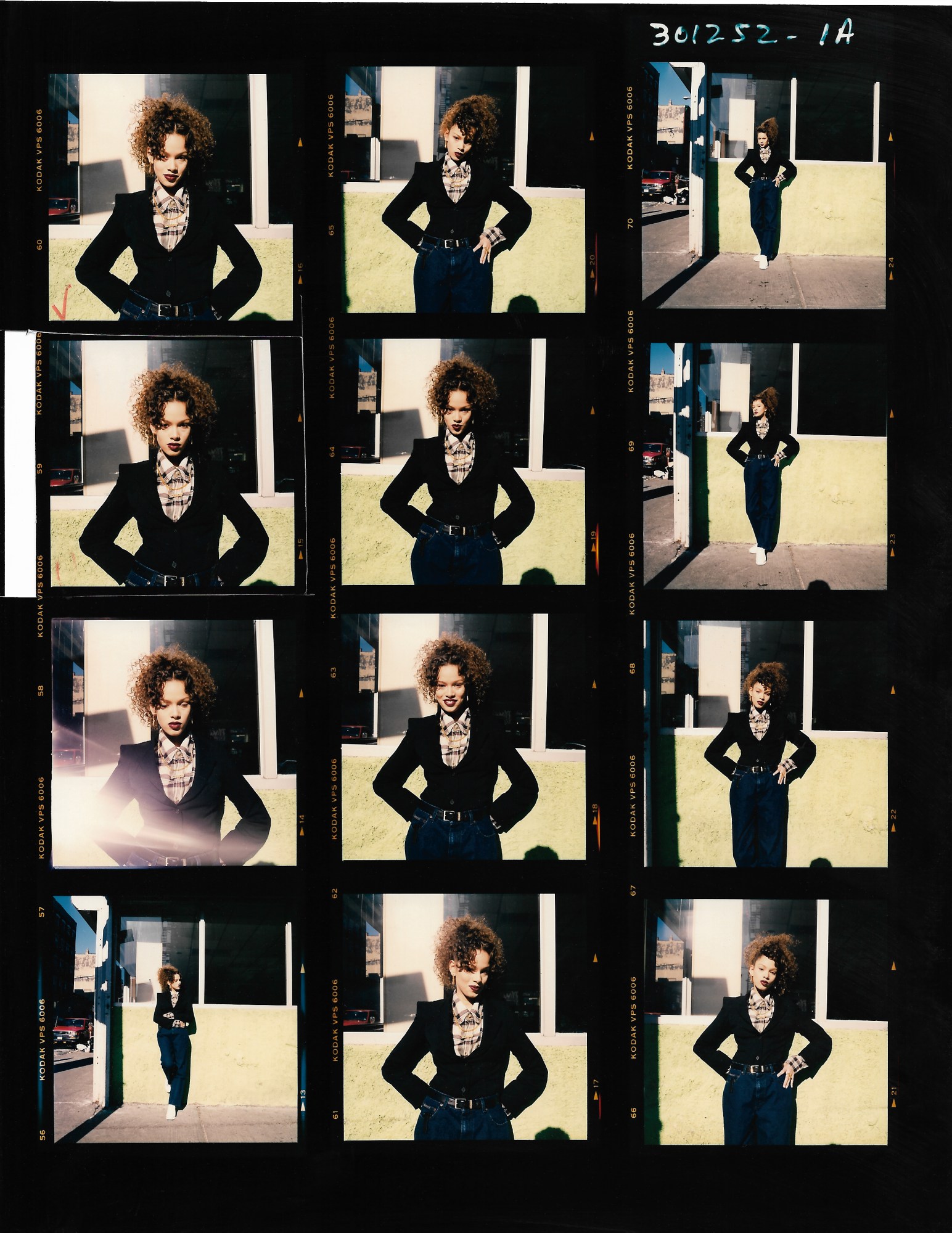

In 1994, “heroin chic” held fashion in a feverish grip, its gaunt and predominantly white ideal of beauty flouting a brutal truth in advertising. But as the nihilist aesthetic reached its logical conclusion, a new generation of artists entered the industry from the world of hip-hop culture. Among them was Jamil GS, who moved to New York in 1990 to launch his photography career. “I was schooled in fashion, working with fashion photographer Patrik Andersson, who was shooting Naomi, Kate, and all the supermodels and I could have easily gone the safe commercial route,” Jamil says by phone from his home in Copenhagen. “But when I clocked out of work, I went to the hip-hop clubs. I didn’t go to the fashion parties. It’s not that I didn’t want to work with fashion, I just saw the opportunity to show it my way.”

Hailing from Copenhagen, Jamil fell in love with hip-hop while visiting Harlem in the early 80s with his father, saxophonist Sahib Shihab, one of the founding members of Bebop jazz. He became a B-boy devoted to the four elements of hip-hop, but after members of his crew got busted for writing graffiti, Jamil traded in the spray can for the camera his father had given him at age 16.

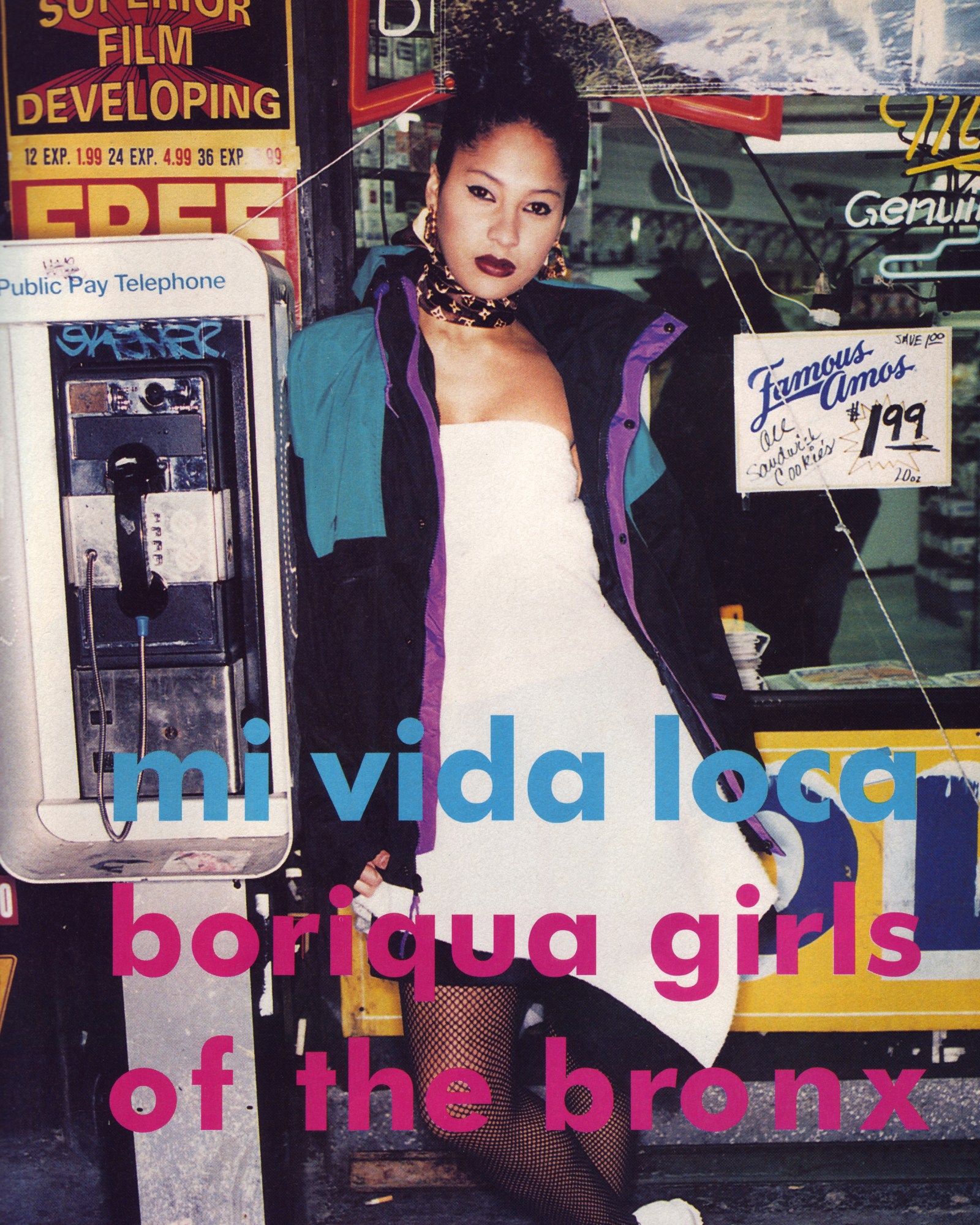

While travelling through London in 1994, Jamil showed his portfolio to i-D fashion director Edward Enninful, and soon began photographing the hip-hop and R&B artists he loved for the magazine. The first story he pitched was “Boriqua Girls of the Bronx”: a fashion editorial showcasing Puerto Rican models shot in the streets of New York.

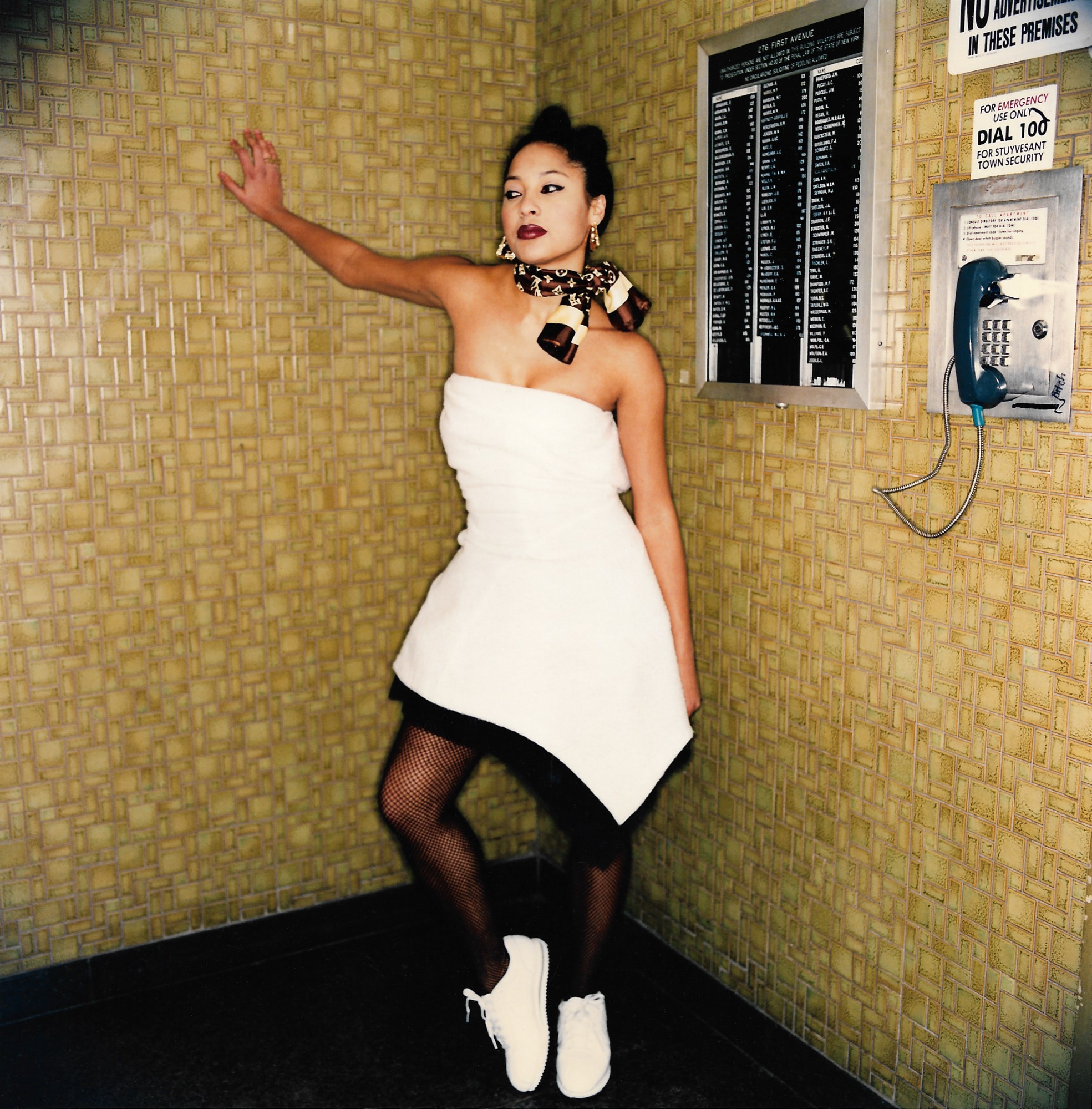

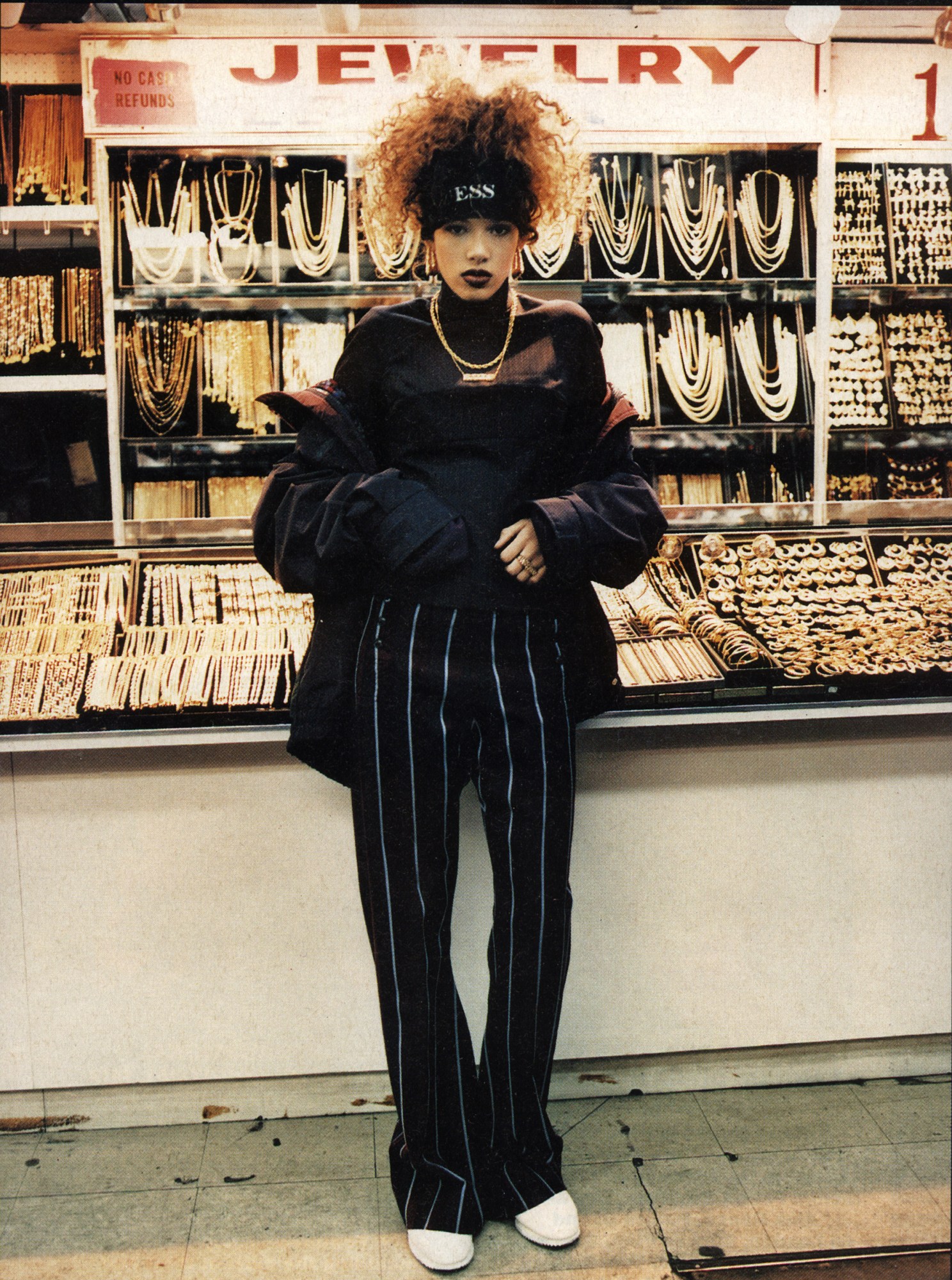

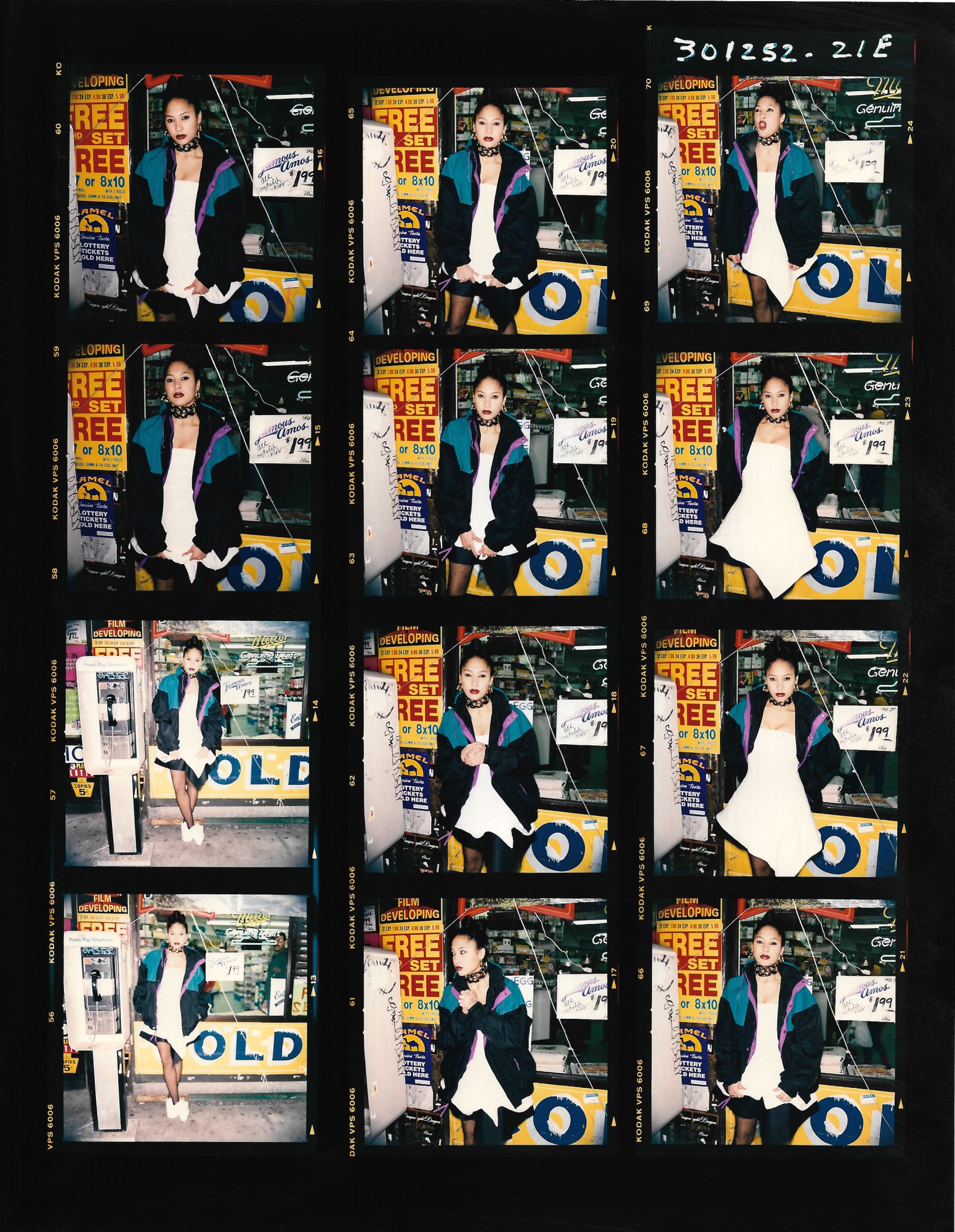

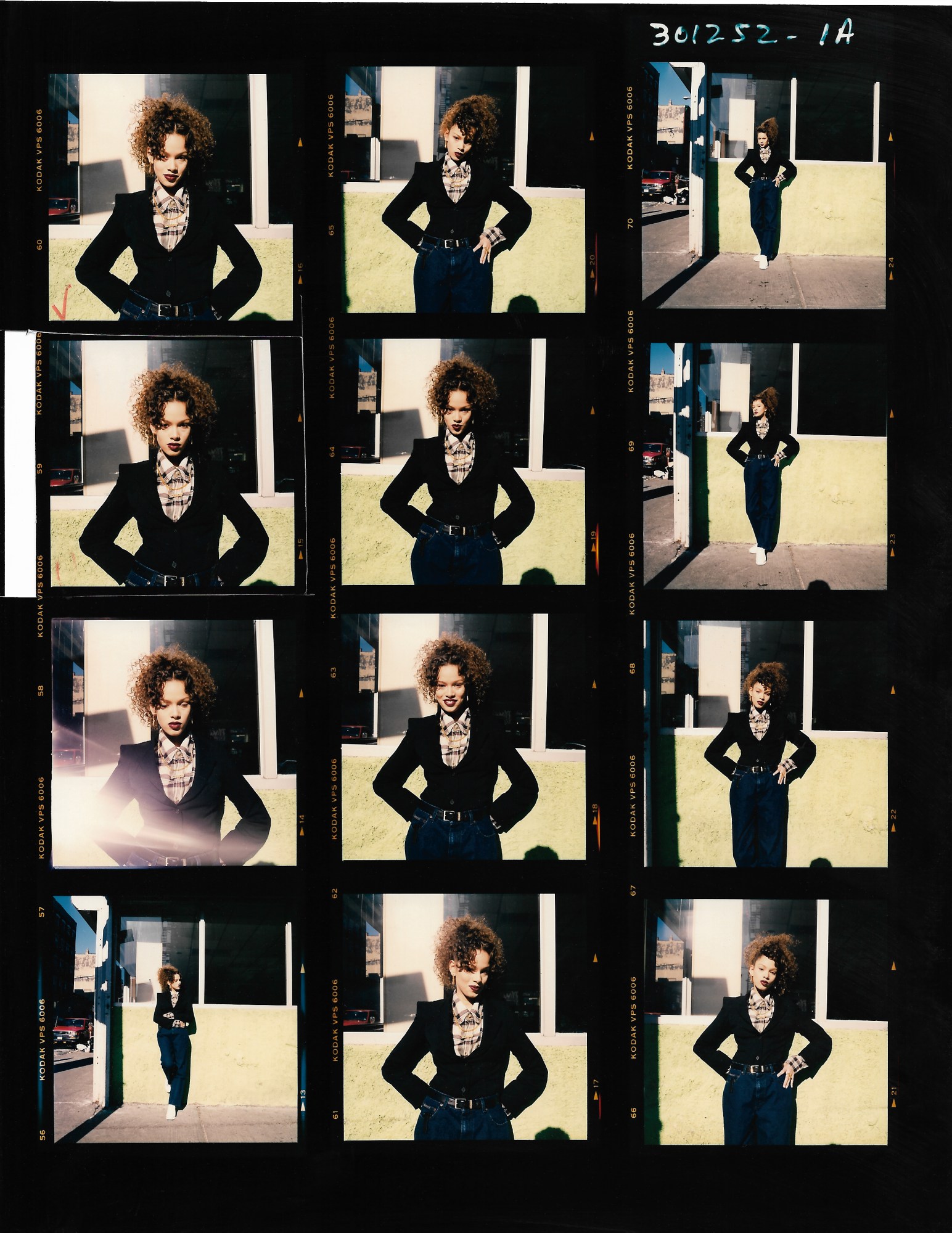

Along with makeup artist Sade Boyewa El, hairstylists Chuck Amos and Pep Gay, and stylist Bernadette Van Huy, Jamil embarked on a multi-day shoot across New York’s Lower East Side for the story, where both he and Sade lived. “We were young, enthusiastic, and we had all these ideas,” says Sade, now a Harlem-based photographer and curator. “Jamil lived on Avenue A, in this really fabulous loft. We had such a good time. We didn’t have a lot of means to create so the street became our studio. Everything was very accessible. It was like your playground.”

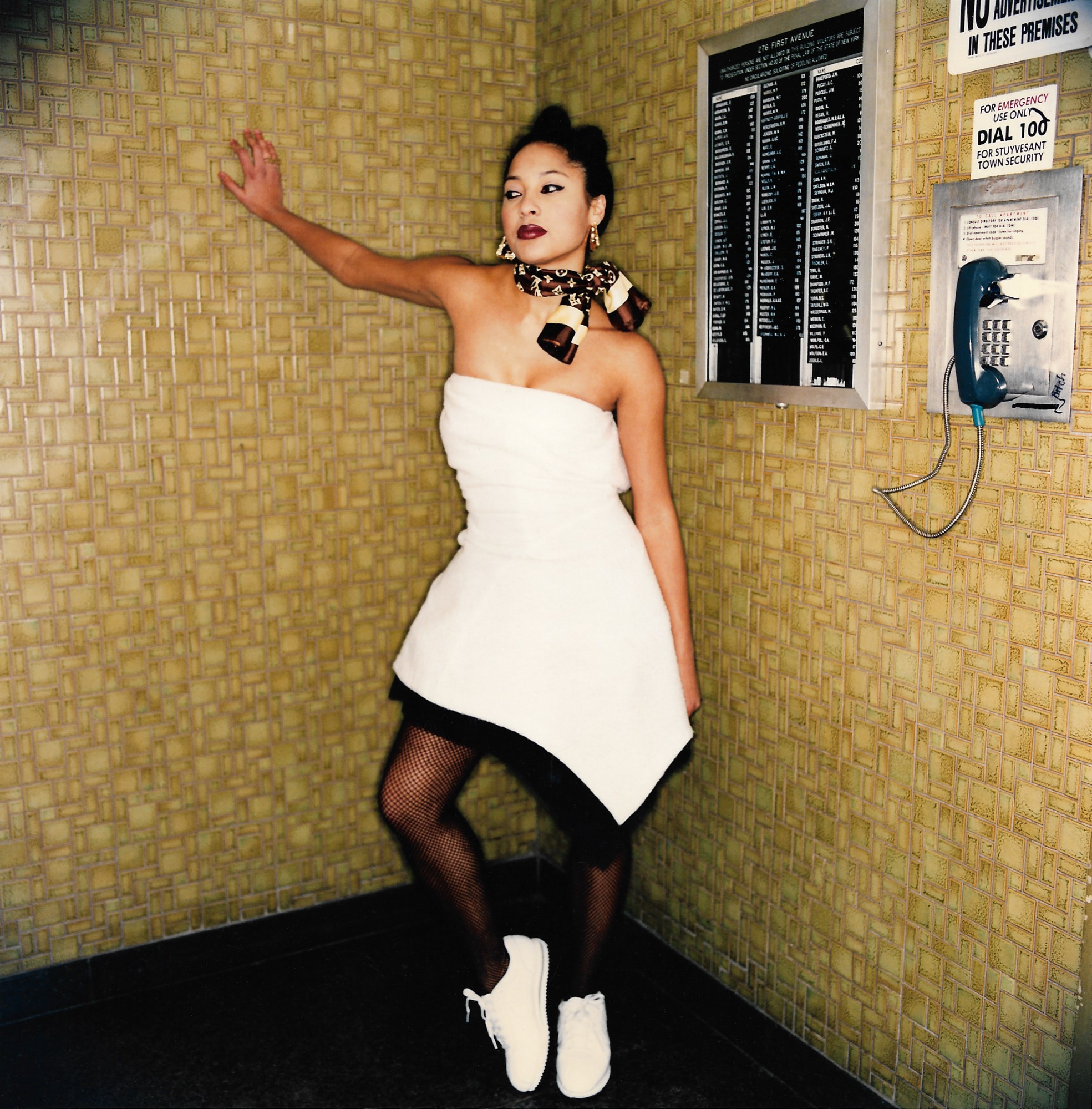

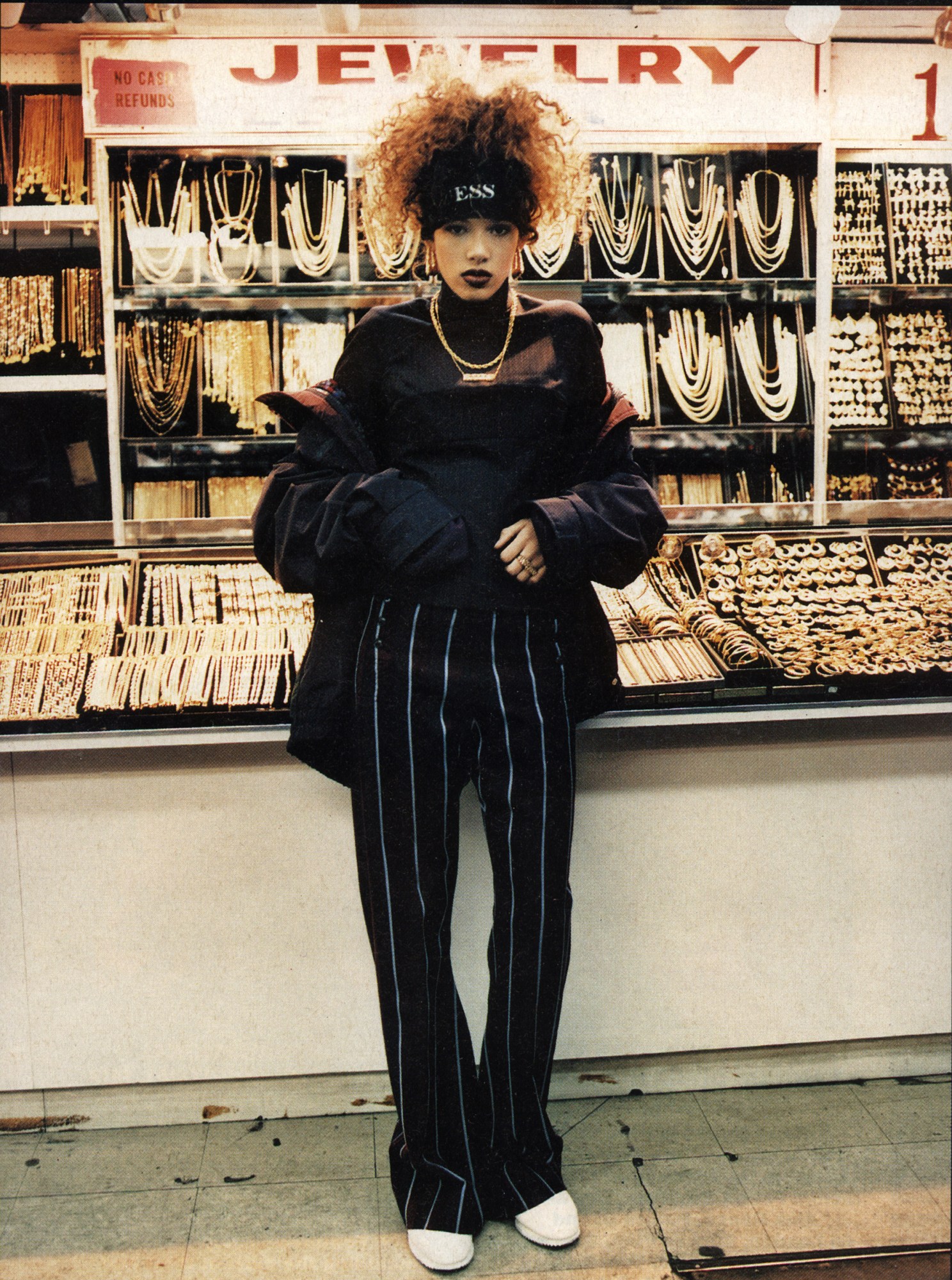

First published in the May 1995 issue of i-D, “Boriqua Girls of the Bronx” combined high fashion and streetwear. It was a watershed moment, and it was long overdue.

“We couldn’t use Naomi because she was with an agency, so we were just like, Yo, we’re just gonna find the hardest chicks in the hood.”

Sade Boyewa El, make-up artist

The story featured Yalitza Rodriguez, Mai-Ling, Assia, Anette, and Sally, all new faces from the Bronx. “I am Puerto Rican and Dominican and my sis Mai is Puerto Rican; they called us ‘cookie and cream’ when we were kids,” says Yalitza (Yali), now a stay-at-home mother of two. “We went to elementary school together, junior high, and now she lives here in Florida, down the block from me. I would say, in our time together, we were a menace [laughs]. We were 14 and 15. Grand Concourse was our meet up spot; we rode the trains to do modelling gigs, then sometimes [ended up in] luxury taxis and limos. I was a teen model, going to lots of clubs, dancing, travelling, and having a good time.”

Jamil had spotted Yali in the neighbourhood, walking with her brother Giorgio, a stylist who was instrumental in getting his little sis her first big break: a photo shoot as Mother Teresa as seen by David LaChapelle. “I was a little girl scared out of my mind, but it was so colourful; there were flying angels and acrobatics,” Yali remembers. “David came up to me with a wig on and he looked like a beautiful blonde angel goddess. Then he snatched his wig off, and I was like, ‘Oh my God!’”

In front of the camera, Yali showed no fear, her baby face a vision of serenity and grace. A decade later, she embodied the spirit of the times.

The shoot day was electric. Taking inspiration from documentary photographers like Roy DeCavara, Bruce Davidson, and Leonard Freed, Jamil transformed the Lower East Side into an outdoor studio. They went down to Clinton Street, around the Williamsburg Bridge, and along an overpass to East River Park, Jamil attuned to every detail in the shot. “My focus is the people I photograph, but I am very specific about picking the locations,” he says. “I used to be a graffiti writer, so I’m always looking for a place to get up and the textures of a beautiful canvas. I like to shoot during the Golden Hour, seeing the environment change colour with the light going from a warm glow to an electric blue sky, and then street lamps come on.”

The story paired Comme des Garçons, Yves Saint Laurent, and Gucci with Polo, Guess, and the Gap, big curls, gold chains, door knocker earrings, and most daringly of all: Nike trainers. “i-D wanted to kill some of the pages that had sneakers in them,” Jamil recalls. “You couldn’t get in a club with sneakers on back then, and the fashion world hadn’t embraced sneaker style yet.” But the team won out, the kicks stayed in the picture, and fashion history was made. “We couldn’t afford the stuff that was on the runway,” Sade remembers. “We went thrifting, found it, stacked it, and laid it. If we were able to get designer clothing, maybe we would incorporate one piece and the rest of it was jewellery from Canal Street. We brought style from our neighbourhood.”

“We were innovators. It’s the only thing we knew how to do,” says Sade of their creative crowd. “We didn’t have it easy, just being who we were, being where we were at, and not having things [many other] photographers had. Everything was so raw because there was no retouching or airbrushing. We didn’t need to bring high fashion into our world because there is so much beauty that exists within the hood. But it wasn’t Vogue. It was strictly street.

In that moment, Boriqua girls claimed their rightful place among the 90s style icons, embodying the DIY spirit of hip-hop as it was born in the Bronx. “I was incorporating different elements of the culture and celebrating multiculturalism. That’s something that I continue to do; it’s part of my DNA,” says Jamil, who showed selections from the series in Frequencies at MILAAP in Hellerup, Denmark, this Autumn. The exhibition showcased Jamil’s portraits of Donald Byrd (1994), Jay-Z (1995), and Drake (2019), framed by smaller works that traced his innovative practice over three decades. “The picture of Drake was flanked by images from shoots I did [in the 90s] with Usher, Juvenile, and Cash Money Click,” he says. “As we went along, I found out Drake was heavily inspired by those sessions while he was coming up as an artist.”

After becoming the youngest artist to be featured in the 1997 exhibition, Contemporary Fashion Photography at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, Jamil forged his own path working across the landscape of commercial and fine art, effortlessly helping to blur the once hard boundary between the two. Whether collaborating with Kaws, Hysteric Glamour and Supreme or exhibiting alongside Juergen Teller, Richard Avedon, and Irving Penn, Jamil’s influence on fashion photography is undeniable.

“There was a time when there were standards for models: you had to be a certain height, shape, skin colour, and the makeup and hair products just didn’t exist,” remembers Sade. “I did a lot of castings to get these models onto the pages. We couldn’t use Naomi [Campbell] because she was with an agency, so we were just like, Yo, we’re just gonna find the hardest chicks in the hood.”

“I saw all this beauty around me and I was driven by what I wanted to see,” Jamil says. “I wanted to bring it to the front and show it to the world. We weren’t waiting around for someone else’s platform. We were the platform.”

Photography: Courtesy of Jamil GS

Text: Miss Rosen