November marks the first time Rick Owens has voted in an American election. “I shouldn’t say this, but I’ve never really cared. If I had children I would take all this more seriously, but I ended up being a selfish creator. I’m kind of living in my own little sandbox,” he admits, looking out on the Adriatic Sea from a sofa in his Venice condo. “But on this one, we can’t let 1939 happen again,” he shrugs. Owens has been in a reflective mood this summer, in self-imposed exile from his Parisian headquarters in his new home on the Lido, o solo mio bar the employees, who take turns staying in the guest apartment downstairs while Owens designs his women’s collection. It’s not far from the abandoned Grand Hotel des Bains where Thomas Mann’s brooding protagonist first disembarked a boat in Death in Venice circa 1912. Immortalized by Dirk Bogarde on Luchino Visconti’s silver screen half a century later, his ghost still haunts the Venetian sandbar.

“Mortality is always on the surface with me. I’ve been thinking about that this month because of the whole Death in Venice connection, but also, everything I’ve been reading recently is biographies of dead literary queens.” They include: Lord Berners, Ronald Firbank, James Lord, Denton Welch, and of course Bogarde. “It must be this whole Venice thing. But also the whole political climate now; all this divisiveness; the male ego in American politics.” Just back from his daily beach rounds, a barefoot Rick Owens is sauntering around his holiday abode, clad in something black and drapey (his take on shorts and a T-shirt), his tanned skin sizzling on his ripped body. There’s a salt-watered tousle to his long, undercut raven hair. The top floors of one of the biscotti-beige apartment blocks from the 60s that line the unassuming east side of the island, his refuge is a far cry from the candy-colored palazzi and baroque beach hotels you’d picture.

“It’s so non-fabulous, even though it’s fabulous,” he says and breaks open the doors to a cupboard that transforms into a kitchen. The same room houses his gym equipment, a compact concept that runs through the condo he’s been Rick-ifying since he bought it last summer. “It looked very World of Interiors,” he recalls, describing the turquoise and orange tiles and color-blocked walls he’s now refined to white Venetian waxed plaster (Marmorino, he says, is fake), grey stone floors, and sprawling custom-made Rick Owens sofas like something out of a brutalist beach house. Down the road is the Palazzo del Cinema, which hosts the Venice Film Festival. “It’s this Mussolini marble building with columns and it was always my dream to live there. So I thought, this needs to be Mussolini’s bathroom.” Unlike the writer in Death in Venice, Owens hasn’t come to the Lido to beat a creative block. Like him, though, he is here because something on his horizon has changed.

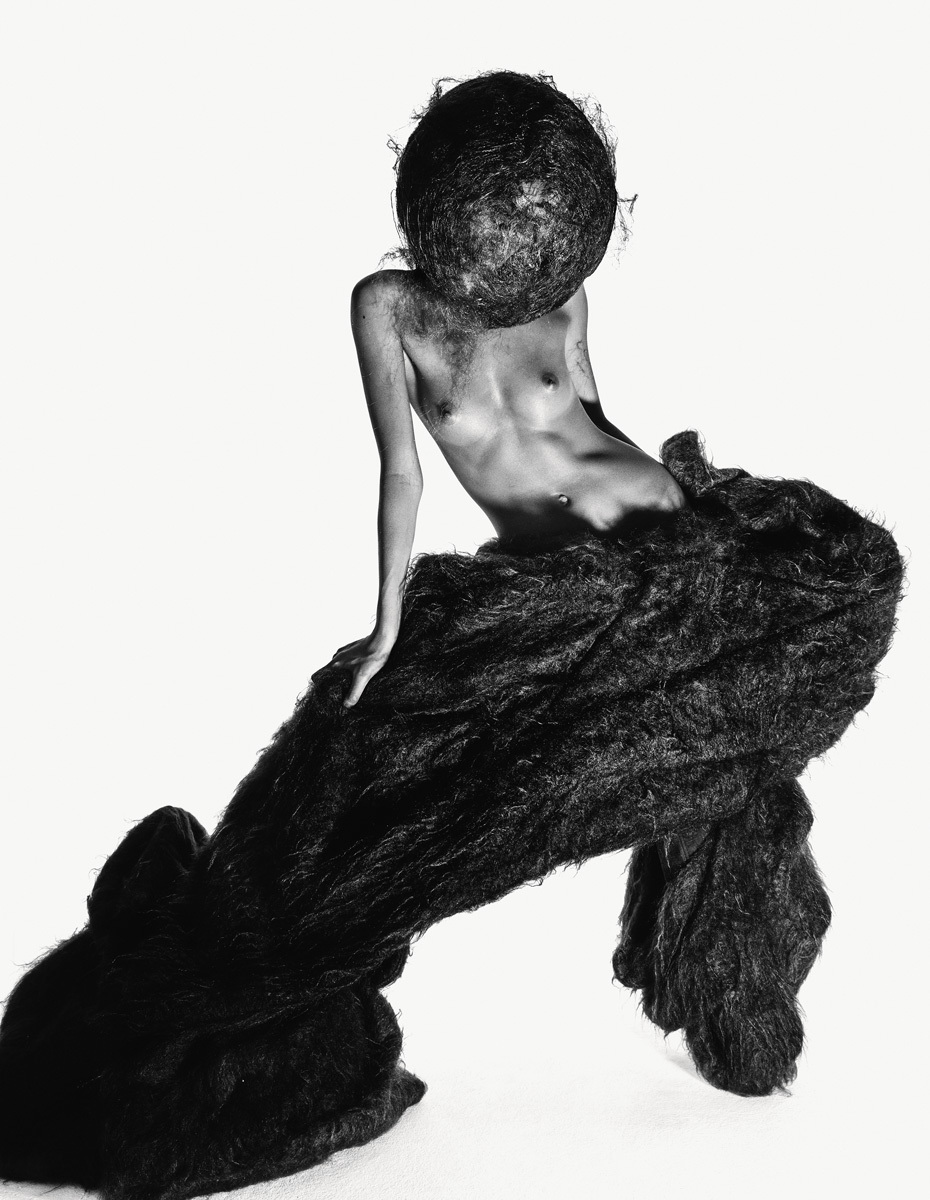

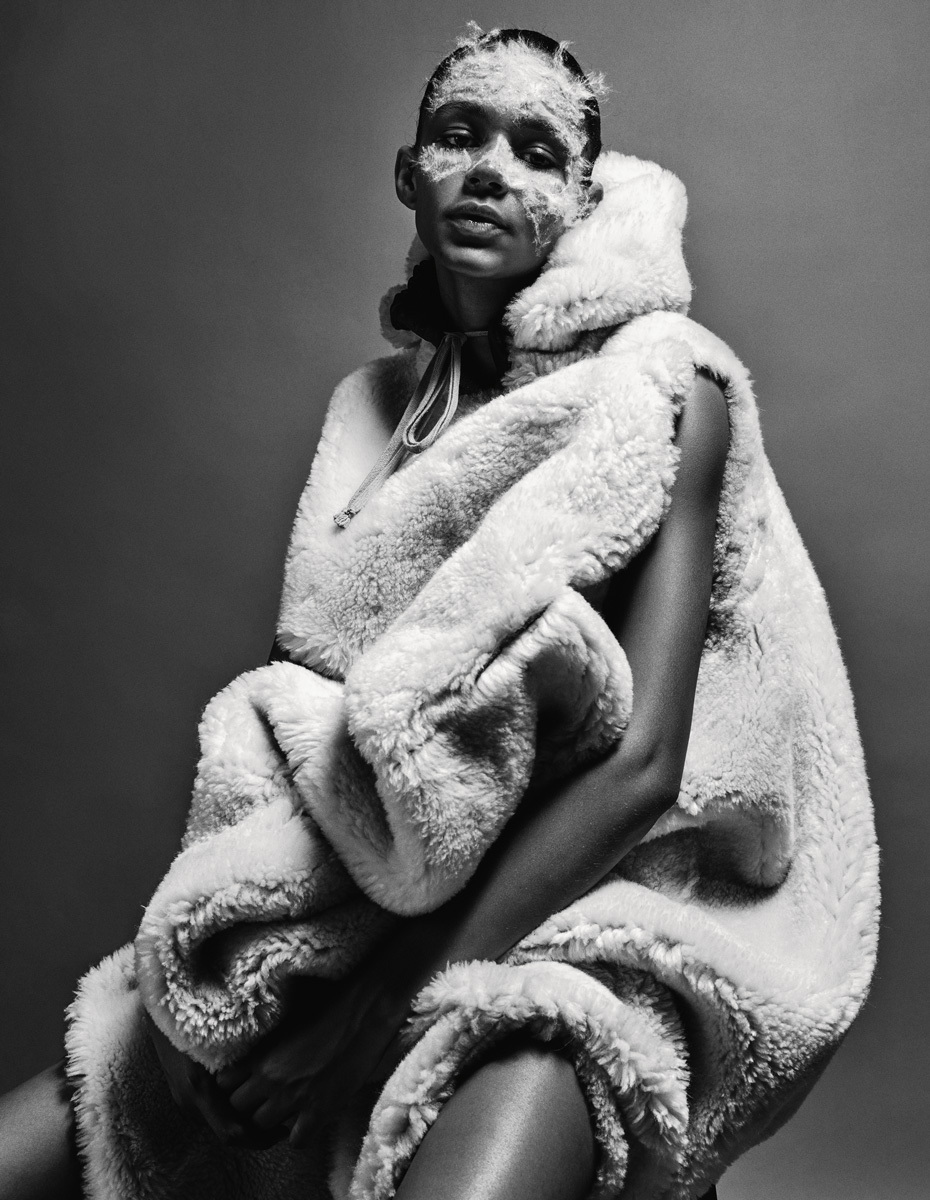

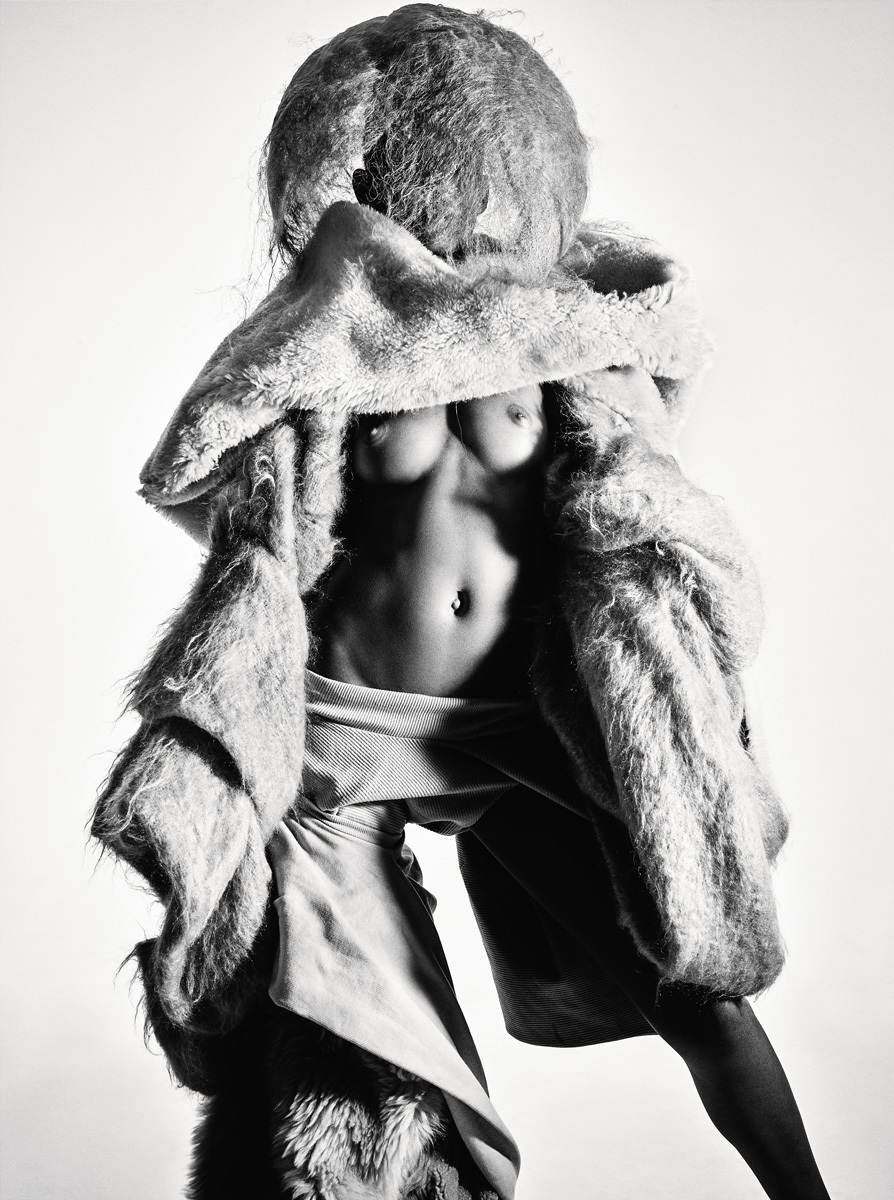

After seasons of camp mega shows featuring acrobats suspended from the ceiling, sorority step dancers and Eurovision reject rockers Winny Puhh, two years ago — around the time he’d turned 50 — Owens decided to pull back. In the seasons that followed, his collections became less severe and more romantic, more couture. The shows turned into humanitarian observations, from the provocative such as the glory-holed man-dresses revealing boys’ genitals, to the compassionate in women carrying other women on their backs. “I thought, I can make it more intense by distilling all of it into a smaller visible gesture.” The zenith of his belle époque, Owens draped his entire fall/winter 16 women’s collection himself, isolated in his studio reconnecting with the fundamental values of his craft and creating a signature that could never be reproduced by anyone else.

He iced his dreamy drapery with giant veil-like hairballs, evoking a softness he related to “an evaporation into something bigger than us.” Backstage he mused, “Everything has a shelf life. How do we face that in a graceful, positive way? I’m not New Age or Buddhist, I’m just talking about emotions that we can all relate to when change threatens us.” As part of his own evolution, last year Owens bought the factory in Concordia not far from Venice, which he’s worked with for 12 years, as well as an apartment close to it to replace the “serial killer on the run” petrol station motel room he’d always stayed in. He was reassessing his business and himself, thinking about his legacy and trying to patch together what was left of 20 years’ worth of archives — in shambles.

“I got mad. I said, none of you thought we were going to survive long enough that we might need this stuff?” he laughs. “For better or for worse we’re kind of establishment now and I need to think about the future. If the past was about survival the future needs to be about refining what we’ve done. I need to live a certain way now.” Buying this Venetian getaway last year was part of that process. A vision of health thanks to a grueling fitness regime (and not drinking for 25 years), Owens is worlds apart from Bogarde’s bereft and ailing composer in Death in Venice, who contracts cholera and sails into San Marco where a barber dyes his hair and covers him in make-up like the living dead. But the parallel between his and Owens’ storylines remains: the middle-aged creators stranded on the Lido in deep reflection.

Dealing with masculine temperament and the changes we go through with age, the 53-year-old Owens has wondered if his last two men’s collections didn’t represent a type of midlife crisis on his part. “Because decline is inevitable,” he points out. “And the fear of death is one of the greatest motivations to do something while we’re here.” If a boy’s first coming-of-age is rooted in the teenage doom, which very much fed into Owens’ brand from its birth in 1994 onwards, the definite coming-of-age is defined by the loss of a parent. Last year, his father died at 95, subconsciously prompting Owens to read those biographies of men “trying to negotiate their endings.” He talks about Bogarde and his unofficial male lover, who got Alzheimer’s and asked Bogarde to euthanize him with cyanide capsules saved from the war when the time came — a suicide pact disrupted by Bogarde’s stroke. “That’s the way it was with my dad, too,” Owens says, never interrupting his calm Californian flow. “He was getting stuff through the internet to prepare. He never had a chance to use them either. He ended up in a wheelchair with nurses and couldn’t get to his pills.” The only thing he wants from the estate is his dad’s collection of Luger pistols, but it’s been a challenge getting them to Paris. “Dad was trying to make me go halfsies with him on getting an AK-47. Dad was really into guns. Looking back, it’s kind of funny. That’s my memory of him and I like the idea of having them.” Growing up in suburban Porterville, California in the 60s and 70s, the dynamics between Owens and his dad were volatile at best. “He was very actively conservative, so obviously I was a karmic reaction to that. We were affectionate in the sentimental way but fundamentally we were mortal enemies.” A social worker for the welfare department, his dad’s worldview was tainted by scepticism.

“When every day it’s about the conflict between you and the people who are trying to do wrong, that can color the way you think about society; mistrustful, suspicious, disappointed. He had no tact — amazingly insensitive! He was socially a disaster. Obviously he didn’t have any friends,” Owens recalls. “Mom on the other hand is just the sweetest Mexican lady. His attitude about race was so uncomfortable, but the fact that he married a minority and had a child together, I never could figure out how that worked in his head.” After an interview Owens did with the New Yorker in 2008, his dad called him up. Didn’t you call him a Nazi? “I called him an adorable Nazi,” he quips. “Dad was fine with that, but I said that his attitude towards women and gay rights was just really frustrating for me. He was very confrontational intellectually, so I thought that was cool with us. I miscalculated the balance of my having more of a public forum than he did, and that’s what created the problem.”

Observing Owens in the family-oriented, decidedly un-punk environment of the Lido, with its stripy parasols and neat cabanas, his father’s values weren’t totally in vain — even if his son lives an utterly nonconformist life, bisexual and married to the illustrious Michèle Lamy, whom he met in the 80s and founded his brand with. “What’s amazing is that dad had this weird aesthetic side,” Owens notes. “He devoured classical music and Japanese art, so he had this sensitivity that he suppressed.” Consciously or not, it inspired in Owens an eternal obsession with the arts and its masters. (Here he is only a speedboat away from the Biennale, “the Olympics of art”.) He loves Richard Wagner, whose symphonies might pose some serious competition to Visconti’s soul-crushing Gustav Mahler score if Owens ever decides to adapt his own Death in Venice. His favorite architect is Eliel Saarinen, whose gloomy dining suite from 1901 is scattered around the condo. There’s a Joseph Urban vase from the same decade that looks like an alien, and books on the Jugendstil of the era.

At one point Owens wanders off to find more literature, murmuring something about Albert Speer. He just got glasses but like any true intellectual he keeps losing them. “I walk around with them on the top of my head being mad because nobody knows where my glasses are.” He recognizes his father’s conflicting personality traits in other men. “Some men, who have had stores selling the most beautiful, exquisite things, with the most beautiful taste, will end up being these cowboys that are kind of macho-aggressive men.” They’re the people who scream at gondoliers, like Bogarde’s perpetually infuriated protagonist, pent up by unresolved emotions and repressed desires. “Dad’s intellectual bullying of me had good results, and I’ve always wondered if I had a completely well-adjusted family life with a father, who would not allow fear and shame in the house, how would I have turned out?” Owens muses. “I wouldn’t have had anything to react to so I’m grateful for that.”

Sitting on his terrace looking at that blue Venetian lagoon, the melancholy in Owens is evident, even if it contrasts all the freedom and compassion his work stands for. The son has become the opposite of his father — soft on the shell, harder at the core. “Male ego is something I’m always fascinated with because I know it’s been such a driving force for me, and I acknowledge it and I’m aware of it and I’m kind of ashamed of it. But I’m also aware that it’s the way it has to be sometimes.” Now Owens roams his casual holiday retreat in pensive solitude, listening to Peggy Lee, designing his collection, working out, and eating simple dinners of eggs and toast and cheese. “I really withdrew. I found an island and an ivory tower on an island,” he admits, with the ironic distance that often armors his statements. “Paris is great, but when I die I want to die next to the sea.”

It doesn’t have to be on the Lido, he points out, but the fictionally loaded confinements of this escapist sandbar, sunny as it is, are undeniably morose and perfect for it. “It’s been very Death in Venice this month. And then there’s this underlying sense of grit. There hasn’t been a war for a long time and this generation hasn’t really known that kind of war. And I’m suspicious that people are ready for one; that there is some kind of death lust that’s part of our genes. I think people are allowing things to fall in place for something to happen. I think humanity just needs war,” Owens warns. Crossing the lagoon back to the Renaissance water park of San Marco that night, the haunting lyrics to Neil Young’s apocalyptic “After the Gold Rush” — the emotional soundtrack to his men’s show weeks before — echo. “I was thinking about what a friend had said. I was hoping it was a lie.”

Credits

Photography Mario Sorrenti

Fashion Director Alastair McKimm

Hair Duffy at Streeters. Make-up Kanako Takase at Tim Howard Management using Make up For Ever. Nail technician Honey at Exposure using M.A.C Cosmetics. Photography assistance Felix Kim. Lighting technician Lars Beaulieu. Digital technician Johnny Vicari. Styling assistance Lauren Davis, Sydney Rose Thomas. Hair assistance Ryan Mitchell, Mustafa Yanaz. Make-up assistance Yumna. Production Katie Fash, Steve Sutton, Christopher Cassetti. Casting Angus Munro at AM Casting (Streeters NY). Model Binx Walton at Next. All clothing Rick Owens mens and womenswear.