The electronic music festival Coro Fundo was still in full force as the sun rose outside the warehouse it occupied in Rio de Janeiro’s Gamboa neighbourhood. Pedro Pinho snapped a photo of a woman with fuschia pink hair stretching her hands towards a beam of light in worship. Similar to the churches he used to attend in his native Brazil, the photographer found revellers here reaching towards a state of transcendence. “When you worship, you are connecting to something that’s bigger than you, that you share with other people. And that makes your life better,” he says. “Electronic music is the same thing.”

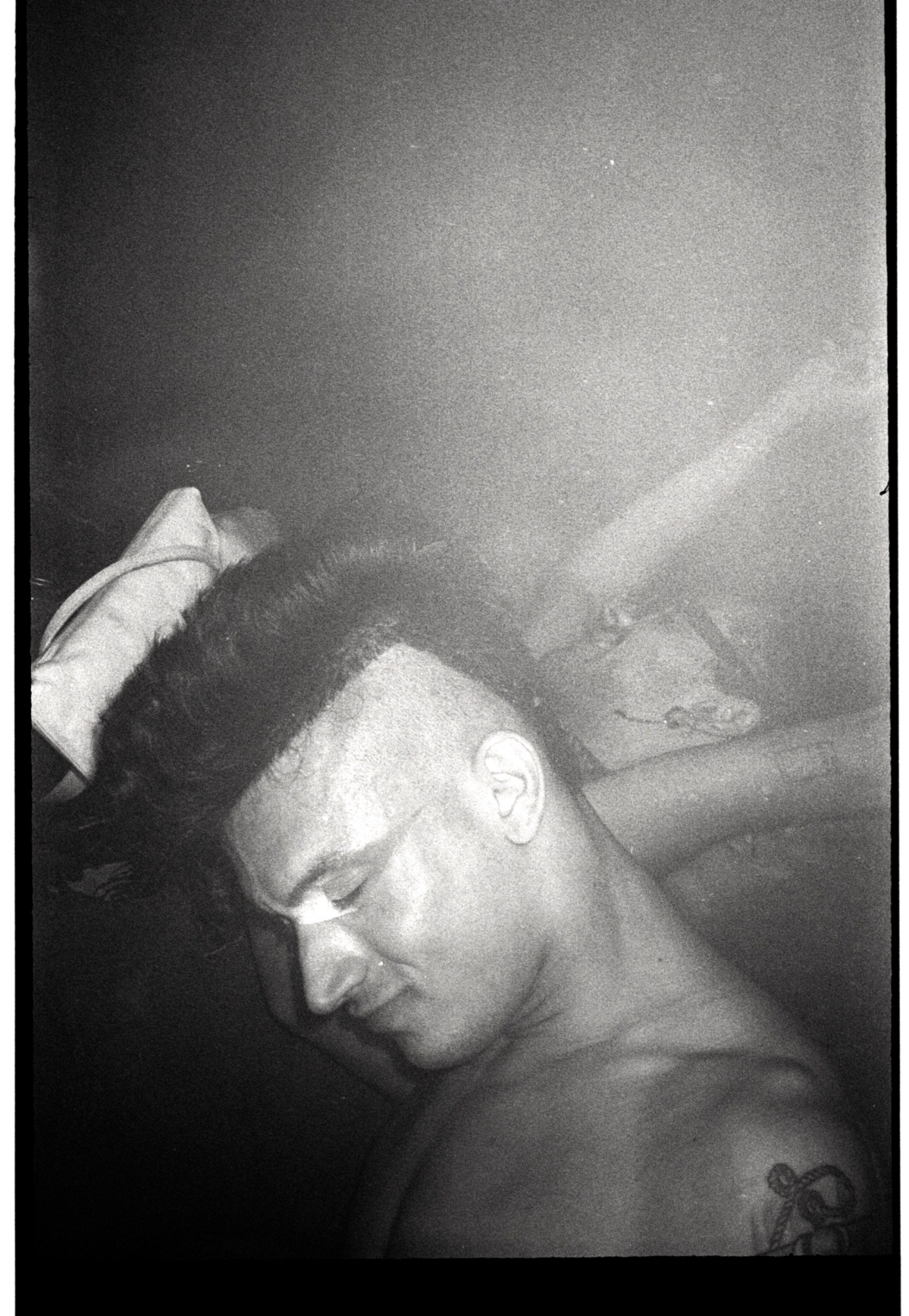

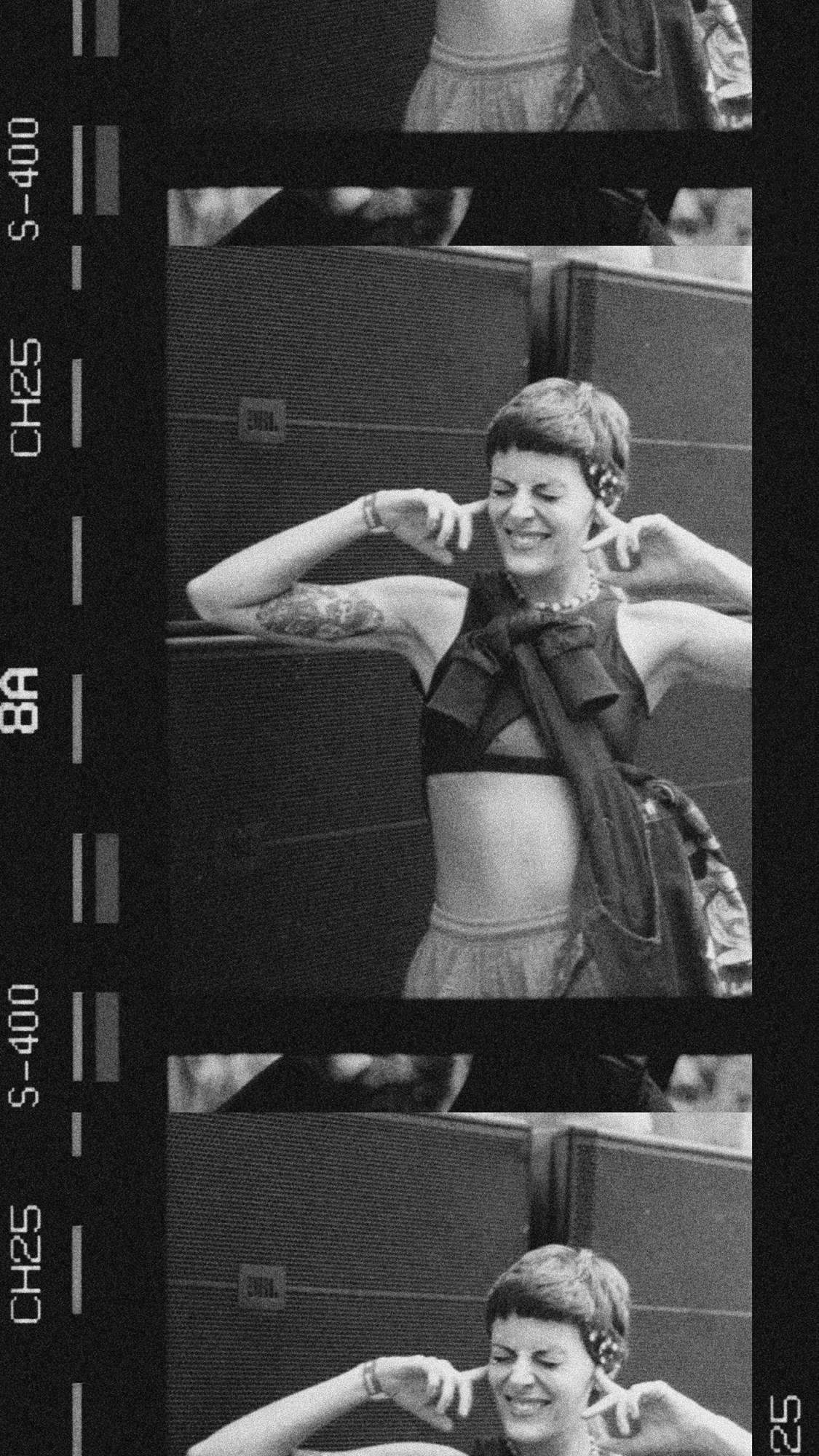

For the better part of a decade, Pedro has documented queer-friendly nightlife scenes, like this one, where outsiders suppressed by the white, ruling elite in their daily lives find power in a collective experience. Moving in rapid repetition for long periods of time — in sync with thousands of other bodies — feels much like a religious ritual, he says. “It is a perfect place to remove your body physically from all that society is dictating on it, and connect to other bodies in different ways.”

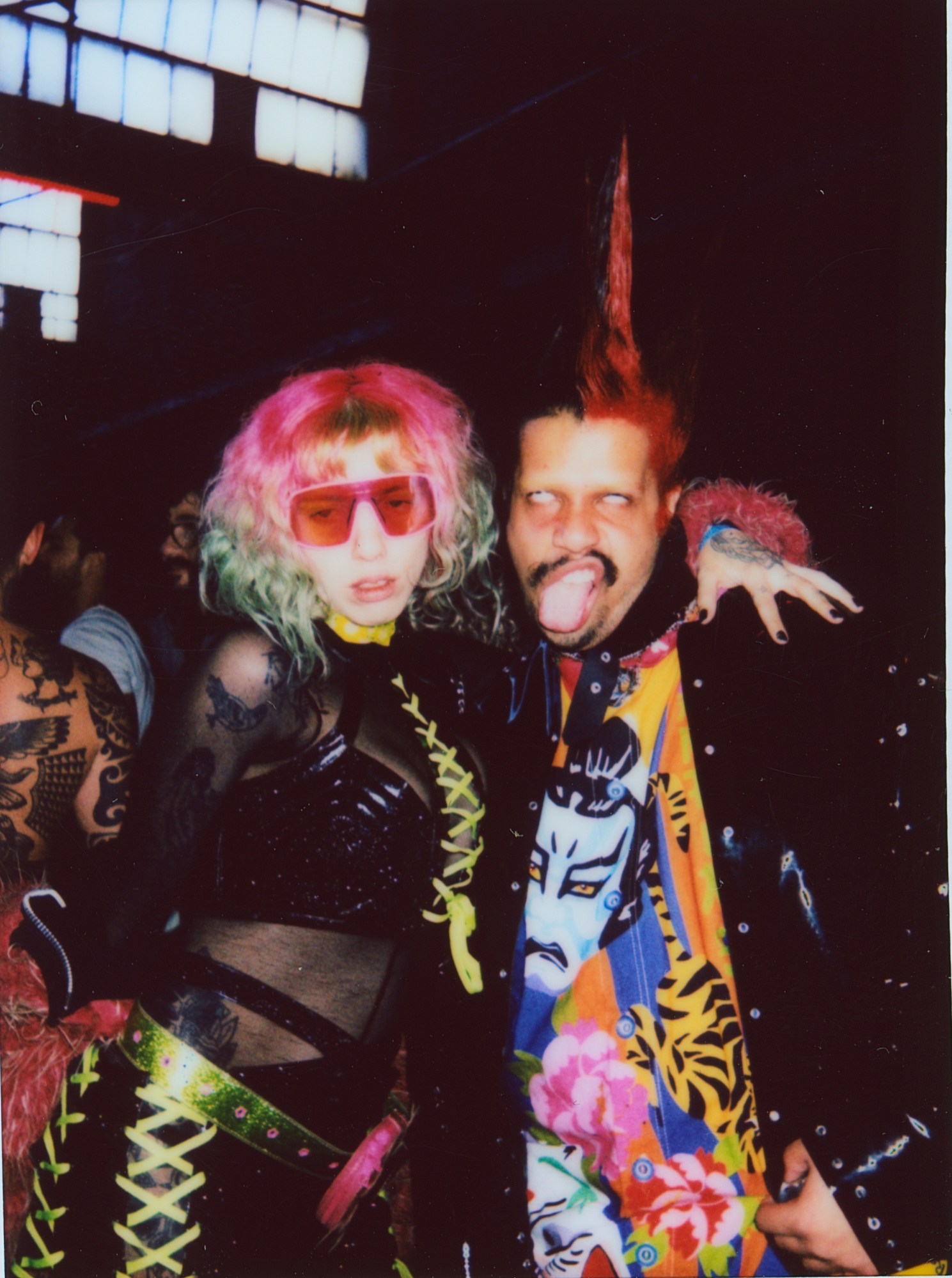

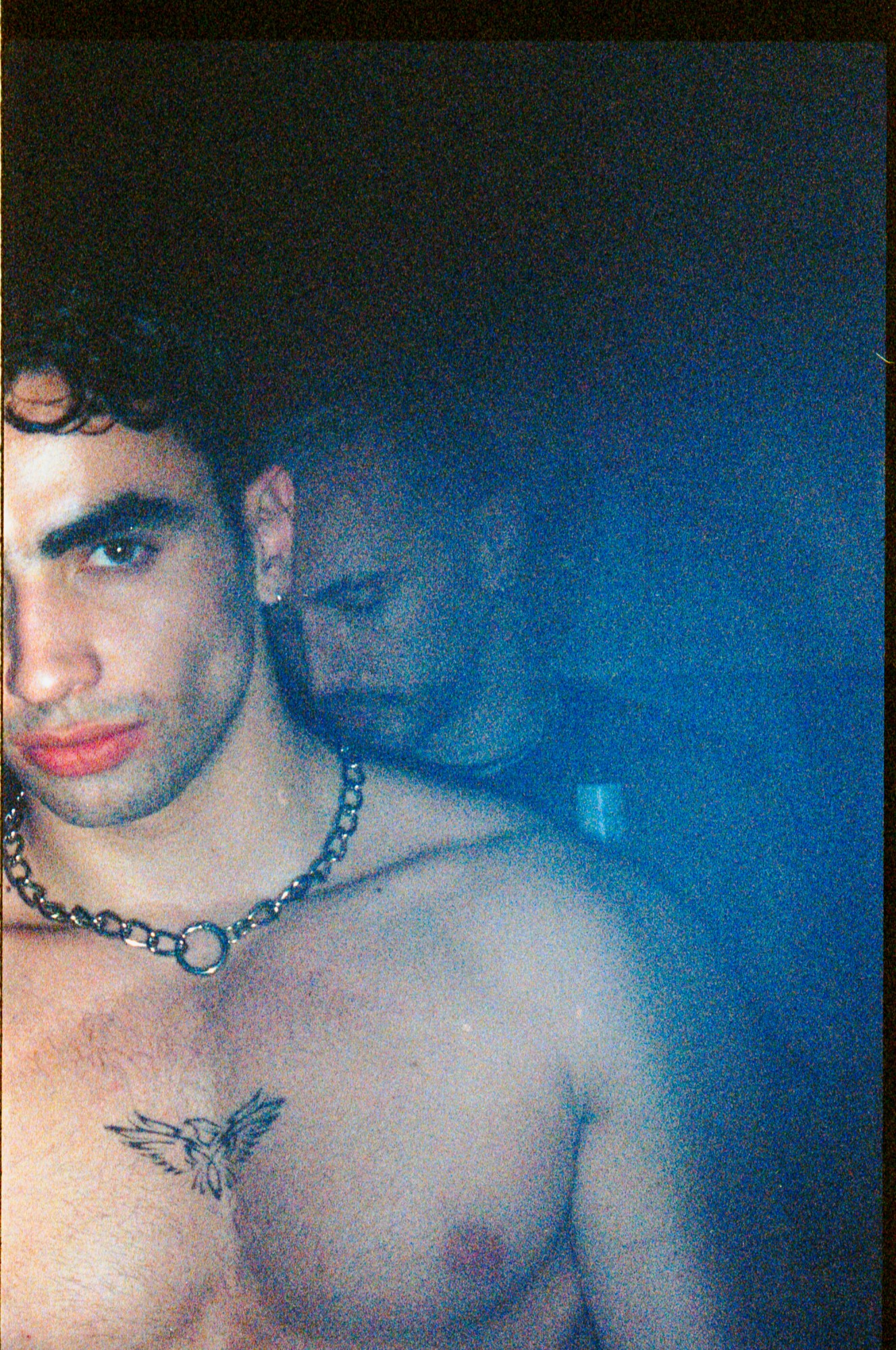

“A lot of our perception of people comes from their bodies and the media is incessantly controlling people’s bodies and [prescribing] how you should look,” Pedro adds. “Rave culture in Brazil is marked by a need to go against that.” In his images, one individual showcases a tattoo with the words “faggot” in gothic scripture, others flash boobs and bums in liberal fashion – a spectrum of gender identities celebrated. “It’s a place where you can go and find different people, shiny and at their best and be accepted for who they are.”

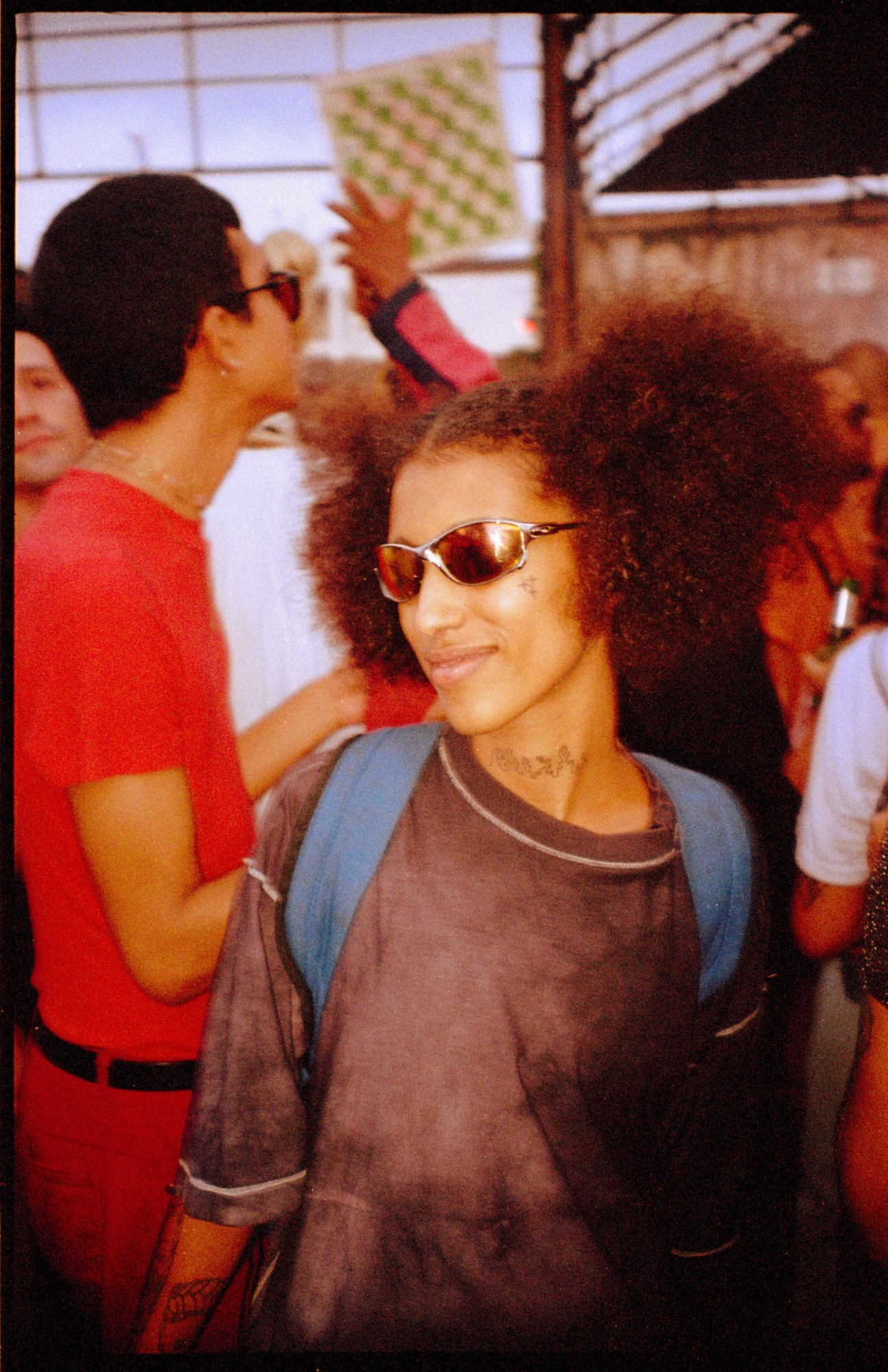

In the dilapidated downtown buildings of Sao Paulo, the green outskirts of Rio and on the idyllic beaches of Bahia, a cultural revolution is taking place in Brazil; one that is intrinsically political. Away from the swanky clubs of the rich city centres, an underground scene has emerged in the shadows, where nights run by the likes of Mamba Negra — an anti-capitalist collective helmed by Laura Diaz and Carol Schutzer, who try to ensure no white men are involved in the creation of their diverse, wild parties — and Batekoo, a Black centric rave and queer entertainment platform, celebrate diversity.

Since the far-right leader Jair Bolsonaro came to power in 2019, his government has been accused of “genocide” by indigenous communities been denounced for policies which devastate the environment, slashed public funds for musicians, filmmakers and artists in what seems to be a punishment for opposing him, decreased federal spending on public health, education and research in a way that affects those living with HIV/AIDS, and can be blamed for one of the world’s highest Covid death tolls (he claimed vaccines might turn recipients into alligators and massively under ordered the lifesaving drugs). As a result, raves have become politically engaged: used as a tool to educate people on a range of issues from race to gender, class, politics and gentrification, while offering a safe space for people to be their true selves.

“One thing that’s really nice about Brazil is that it’s very diverse. Rave culture in Sao Paulo speaks to a lot of issues, just because those people are present in our communities,” Pedro says. “We are very conscious and take action on a lot of issues, especially how to think and occupy a city… Sao Paulo is a hard city for Black people to live in, so we do have to talk about that. It’s also a hard city for trans people.” Brazil currently tops the list of countries with the largest number of trans people killed every year. According to trans activist Bruna Benevides, author of a report by the National Association of Transvestites and Transsexuals, these deaths start “long before the trigger is pulled. It’s in the insults, the evictions from home, the lack of job opportunities, it’s at school where gender is never discussed.”

Rave’s celebration of outsiders resonated with the photographer, who as a gay Black man raised in the confines of Brazil’s conservative capital felt rejected by mainstream society and the religion at its core. “Everything that made me who I am, not just being gay, was considered a sin,” Pedro says. “Parties, going out, dancing, even though it’s a part of our culture and a very important aspect of living in Brazil – religious people deny that and forbid that.”

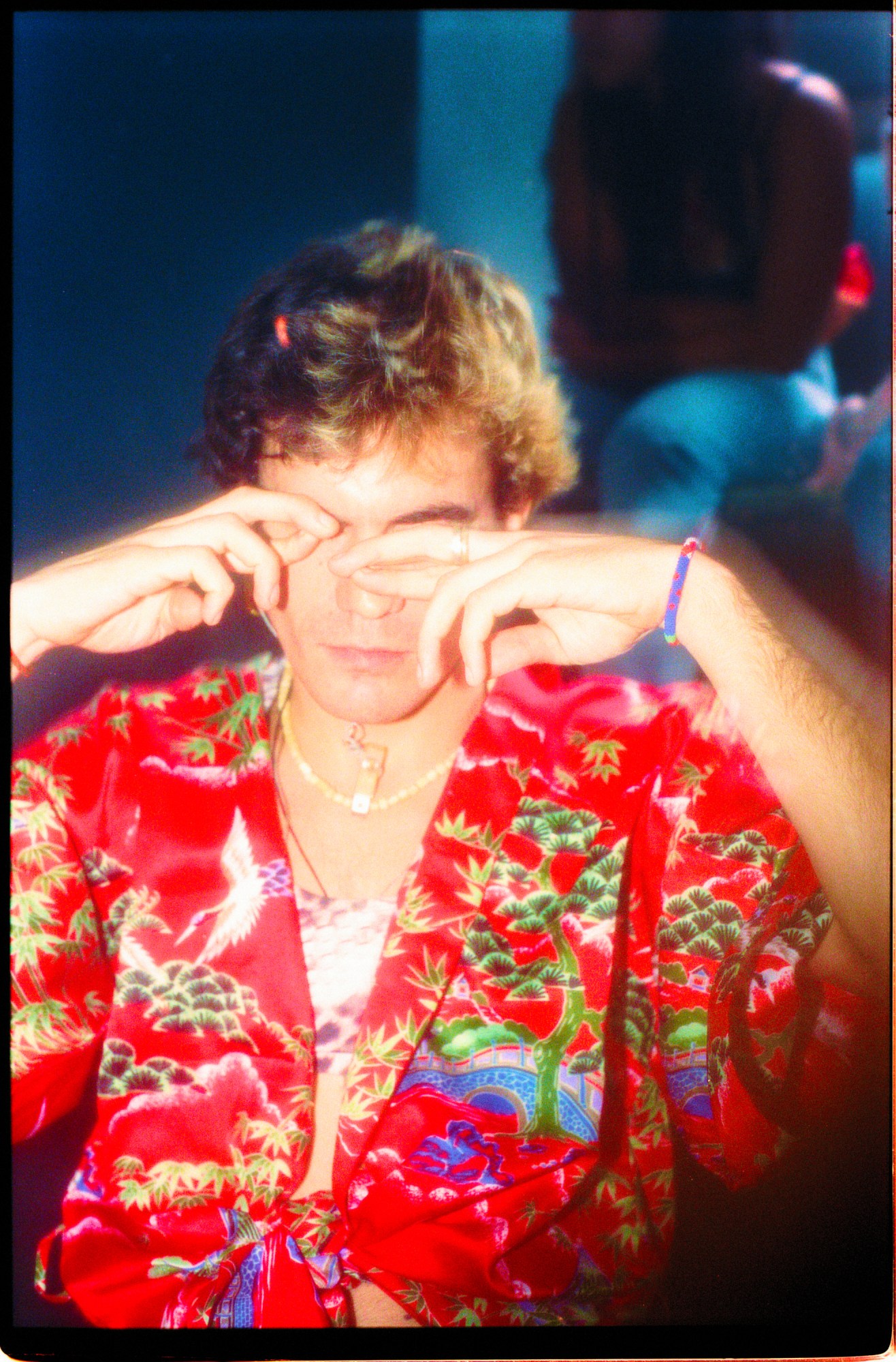

When Pedro moved to Sao Paulo at the age of 24, a progressive government was in power and he found parties across the city, held in public squares that attracted everyone from office workers and street cleaners to queer artists and creatives. Music was celebrated rather than pushed to the fringes. Although times have changed, an underground scene still thrives through Pedro’s lens, as he captures intimate moments in the early hours of the morning when people have been dancing for hours and their inhibitions are long gone.

There’s nothing rigid or posed in his highly exposed shots, taken on an analog camera that chronicles an era that already feels nostalgic: a mix of bleached mullets and flower-embossed buzzcuts, bondage, latex club-fits and glittery makeup, strobe-lit dance floors that heave with dancers, and performers waving flares and flames. The images are intimate, his subjects captured as they would have been by a friend. And perhaps unsurprisingly many of the people he has photographed since the early 2010s have become friends or lovers. “You would meet the same people and they became your family after a while. People really took care of each other, just like in a church.”