Lexie Smith’s interest in baking her own bread first came about as a teenager, ironically at the height of Western culture’s gluten phobia. Since, then, she’s been making bread and educating people through her community based art project Bread on Earth, which explores bread’s potential as a social, political, economic and ecological barometer. In essence, what that means is recipes, essays and thoughts on bread, and most topical to today’s moment — a sourdough starter. Lexie is fanatical about the humble, sour loaf and will send you a starter in the mail for your own.

Suddenly, Bread on Earth has been given renewed importance, as seemingly half of Instagram frantically tries to work out how to make their own sourdough, or make flatbreads, scrambling for self-sufficiency post-Sweetgreen at one’s desk. “I think, to see this boom in bread-making right now, and this really, really avid interest … Yes. It’s shocking,” Lexie says of the many emails she now receives. “To get over a thousand people asking me to send them sourdough starter is shocking. At the same time, you’re like, ‘It’s everywhere. It means everything’”. At the same time, however, she laughs, “At the end of the day, it’s always just bread.”

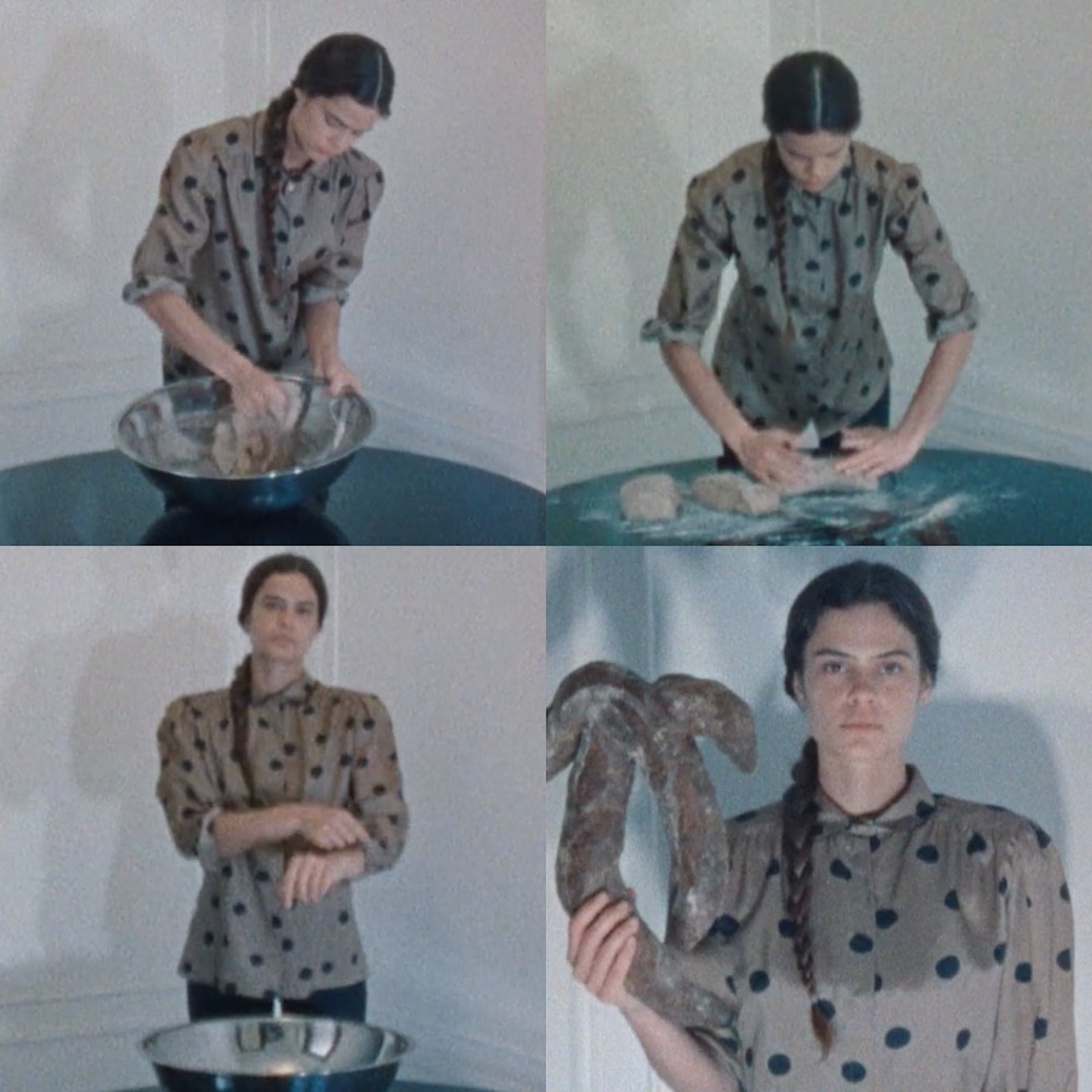

Lexie called i-D to talk about the politics of bread, bread around the world and more bread. You can watch her recipe video, directed by Yasmine Diba, below, and sign up for your own starter on her website.

Interview has been edited for length.

The issue of self-reliance when it comes to food is not a new one for you. Could you talk about how it came to be a driving factor in your life and why?

This interest in self-sufficiency, and shorter supply chains, and having a connection to our food and not relying on commodity markets, et cetera– it isn’t something that is new for me as an interest, but it’s also not something that’s new to a lot of people, all over the world, who just simply do not have the option to be able to make choices about their food.

At this moment, with food, and access, and bread, specifically, the renewed interest in bread-making is sort of showing us that the choice to not make bread is more of a privilege than the choice to eat bread.

In times of scarcity, we move back towards this idea of staples and basics and things that provide us or feel like comfort, but also feel like stability. That is this thing that we have shunned as a culture for the last ten years. That has been replaced with something that essentially could be defined as a luxury, in comparison, which is expensive alternatives.

When did you first start making bread?

I started making bread when I was young, just kind of out of an interest in working with my hands to make something that I could eat, that sort of went through a chemical process, as opposed to an omelet. I think I started with oatmeal, and then I made my first loaf of bread when I was 15, and I was pretty hooked, though I was mostly engaged in baking quick breads and things like that.

I’ve been making bread for, maybe, I’d say, 12 years, pretty consistently. I really started seeing it as a lens for witnessing these shifts and truths, again, in our food systems, and also in our sociopolitical, sociological, economic histories, probably around 2016, when, in the West, we became introduced to what many have experienced all over the place, which is a leader who draws extreme boundaries and moves in a kind of authoritarian way and was really sort of redefining American culture as one that is globally repellent, not just kind of inwardly racist.

I was working a lot with bread. I was researching regional bread types. It was really difficult for me to just move swiftly past the fact that, in the west, we were eating less bread. In the rest of the world, bread was incredibly diverse, but universal, and signified something deeply sacred. Not even virgin holy, but literally holy in a lot of places, historically and still now to this day.

When did your love of bread turn into Bread on Earth?

It felt like a just kind of natural step to start looking at the diversity of bread as a way to hone in on these conversation and translate them to people and have them be something that could be engaged with directly, by those who didn’t necessarily want to have that conversation in the first place, simply because everyone has a relationship to bread.

Especially in New York and in LA and these sort of coastal cities in America, our relationship to bread is very different, but it kind of is the one that defines “contemporary bread culture,” which was really fascinating to me. Bread is so much more an integrated part of the diet everywhere else, yet European still bread is kind of what has been seen for a long time as the sort of apex of bread culture.

The refusal of bread, which is the gluten-free culture, is the other version of contemporary bread culture. Those are both determined by societies that do not necessarily rely on bread for the majority of their caloric intake.

Basically, this is just sort of a long-winded way of saying that, just kind of out of an obsessive delving into this very specific item, I recognized a tool for walking down very diverse pathways and having people be interested in them.

It’s amazing that something which could be so plentiful and cheap, or at least is here, in America, speaks to so many different topics, but it’s also… just bread.

What do people say about you baking bread for them?

I often say, when I’m trying to feed someone sourdough, because I still get pushback — “This is a health food. It is full of fiber and full of protein. It has probiotics in it.” This is a fermented food. Fermented foods are actually proven to better our mental state and help people with depressive issues. Probiotics are actually considered… For what they do in the gut, and then our gut kind of translates to the rest of our body, they are included in diets that are intended to act as a salve and a kind of therapeutic attribute for people who eat them.

The gut is the new frontier!

Right. There’s all of the talk about the microbiome, so then people talk about kimchi and they talk about sauerkraut and they talk about yogurt. Sourdough is the same thing as those.

What’s it like seeing the current re-interest in bread?

Kind of to get back to sort of where we started, I think, to see this boom in bread-making right now, and this really, really avid interest … Yes. It’s shocking. To get over a thousand people asking me to send them sourdough starter is shocking. At the same time, you’re like, “It’s everywhere. It means everything.”

This is what I’ve always been fascinated by and deeply invested in exploring is this idea that bread can take us down any road, if we turn it and look at it at a certain angle.

Suddenly the world is coming to Bread on Earth, as it were. Please, could you explain, in the most basic way, what Bread on Earth does with the sharing of knowledge and sharing of sourdough?

As a sort of general overview, I would say Bread on Earth is a name that I kind of gave this ongoing conversation I was having with this critical study of bread. It was a way, originally, to differentiate it from any other work that I was doing. I didn’t want my identity to be directly in charge of these conversations. I wanted it to be a broader scope, and I didn’t want to necessarily be the author of it.

The point was that it was this realization that this thing affected everybody and was both universal and highly individual and just held within it infinite potential for conversations. It was a name to that idea. It originally was hinged on this project I wanted to do where I would map regional bread types.

And now it seems quite vital.

When the crisis kind of picked up, especially in the United States, as I’m sure you and everybody has read at least one headline about, there’s this yeast shortage and there’s this flower shortage. That didn’t come from actual supply chain breakdown. That came from overbuying in the markets. People got scared and went out and, for maybe the first time ever, bought flower and yeast, lots of flower and lots of yeast.

Even if they hadn’t eaten bread in five years, this idea of being stuck without access to food turned us back to this item that represents safety and stability. I think, at that point, the kind of emotional cure of bread is really secondary, because a lot of people have not been emotionally comforted by bread, at all, for a long time. It’s been like 10 years.

In that 10 years, there’s also been this parallel, simultaneous rejuvenation of bread culture in the states. You can kind of really see it booming in San Francisco. It’s really spread around, especially, oddly enough, through Instagram. It’s become this visual culture. There’s a way that bread is supposed to look, a certain kind of artisan bread, a way it’s supposed to look, a way it’s supposed to be made, a way it’s supposed to be scored.

It’s slightly shameful, because you suddenly realize it’s this thing that you should be self-sufficient, you should be able to make, and you can’t.

Right, but it’s no one’s fault. Even if people wanted to be making bread, the fact is our lives are not set up to provide for that. Everything that we are told about how we’re supposed to live right now takes up all of our time.

Bread is slow. Sourdough bread, specifically, is slow. It is based on intuition and feeling. You have to engage all of your senses. Every time, it’s going to be different. You have to improvise. There’s no stability. There’s no consistency. It is a process that makes us feel vulnerable and could fail over and over again.

Not to mention the fact that we just have lost touch with how to provide for ourselves. That takes generations. We’re probably the worst there’s ever been in modern history, in kind of having a connection to our food sources, because we have so many options that allow us to just not even think about it.

You’re very persuasive.

I’ve been trying to convince people this thing isn’t poison for six years.