Back in the early-1990s, the UK was still recovering from a two year-long recession cited by some analysts as the worst experienced since the 1930s. At the same time, a turbulent post-Soviet Russia had not only just narrowly avoided a civil war, but also seen its own economy head into freefall. So the 1994 music press announcement of an imminent music festival involving Britain and Russia felt surprising and optimistic, but also unprecedented.

Titled Britronica, the four-day event was being jointly organised by Nick Hobbs, a British promoter and one-time frontman of 80s indie-rockers The Shrubs, and the Russian music journalist and art collector Artemy Troitsky. Vibes wise, the festival would be hosting a lineup miles removed from household-name Western acts, like Queen, David Bowie and The Rolling Stones, who had performed behind the Iron Curtain during the 70s and 80s. Instead, Britronica intended to bring to Moscow the most experimental and innovative of the UK’s music creators — the majority of whom were in their twenties — for a series of raves and shows. The festival’s roster spanned emerging and more established names whose output had soundtracked countless illegal raves, secret warehouse parties and after-hours chill-outs, as well as smaller and major club venues across the UK throughout the preceding years: Aphex Twin, Autechre, Seefeel, Paul Oakenfold, Banco De Gaia and Dreadzone, as well as Alex Paterson of The Orb, Reload, Bark Psychosis, Bruce Gilbert from Wire, Ultramarine and Transglobal, among others.

From the moment the motley musical crew landed in Moscow in mid-April 1994, the atmosphere felt unsettling and events went awry. The airport security staff demanded a cash payment before they would authorise taking Ultramarine’s equipment from the plane, for starters. Sarah Peacock from Seefeel remembers feeling an intense feeling of culture shock as soon as the Britronica group arrived. “We all got on a very old bus and drove through mile upon mile of identical vast high-rise housing blocks. There were no shops anywhere, only kiosks lining the streets selling vodka, cigarettes and chocolate,” she says now. “Everywhere people were standing with random stuff in their hands to sell — shoes, clothes, handfuls of herbs.”

After they had checked in at the hotel — converted from a concrete former Soviet conference centre, and home to many-a-cockroach — Peacock later noticed “a steady stream of immaculately made-up women we assumed to be sex workers, arriving and leaving. One floor of the hotel was out-of-bounds and guarded by army officers.”

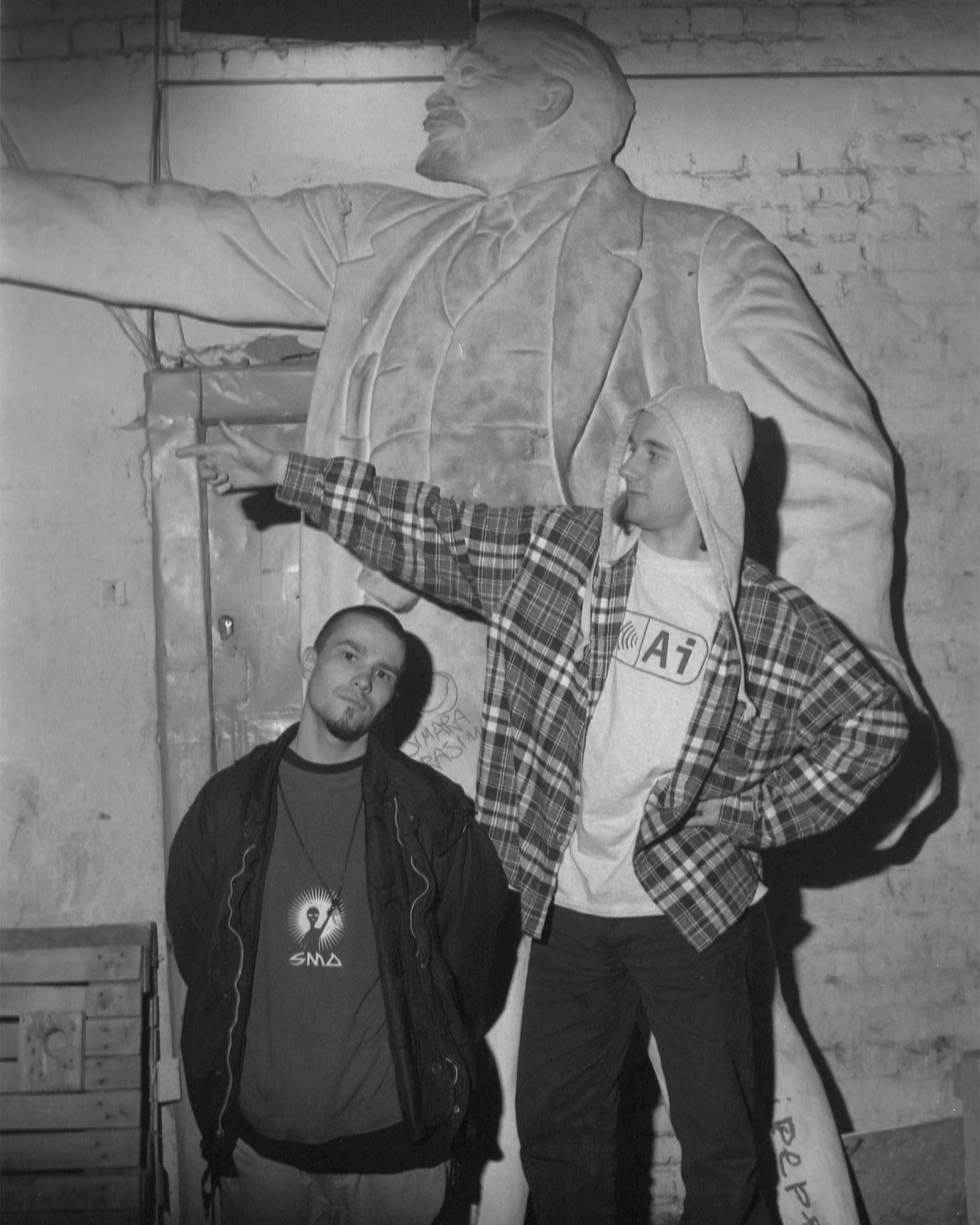

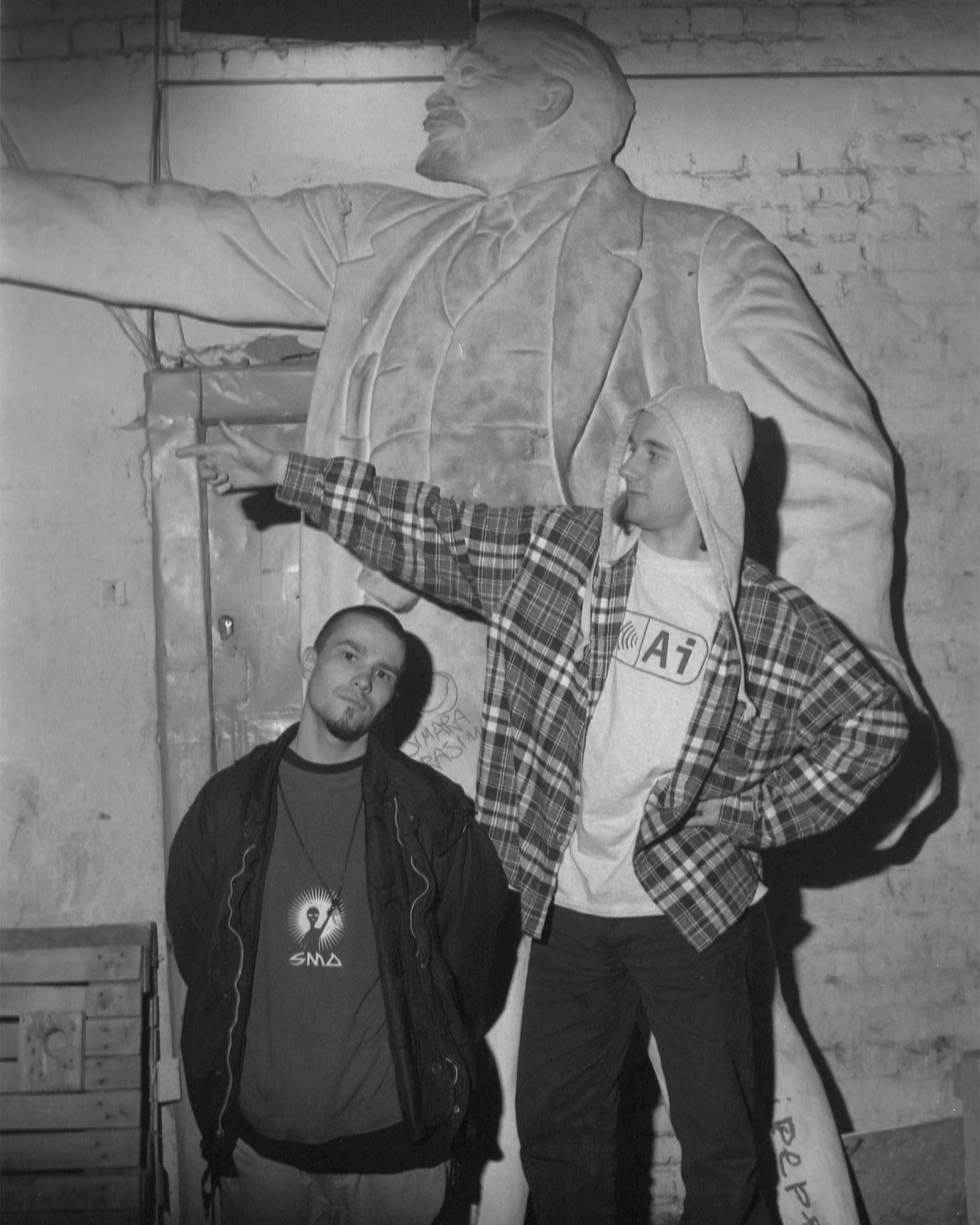

Following a welcome buffet comprising of miscellaneous sliced meats, cabbages, and assorted cartons of juice, the sixty-odd members of the Britronica gang were whisked to a Red Square-based hotel named Manhattan Express for a reception event. It was soon apparent, however, that there was little feeling of joy there. Devoid of young clubbers due to the prohibitive $40 entrance fee, it was instead full of suited middle-aged mafia guys, accompanied by designer frock-wearing sex workers, none of them remotely interested in listening to the ambient dub sounds of Banco De Gaia, who performed later that evening. “Clubs seemed to be mafia-controlled — not a totally unusual situation, but maybe the extent was unusual — and the people in the clubs were ultra-rich,” recalls Mark Pritchard of Reload. “Really, what stuck in my mind was the disparity between the people who had money and the people who didn’t.” This incongruous context would set the tone for much of the ensuing Britronica events.

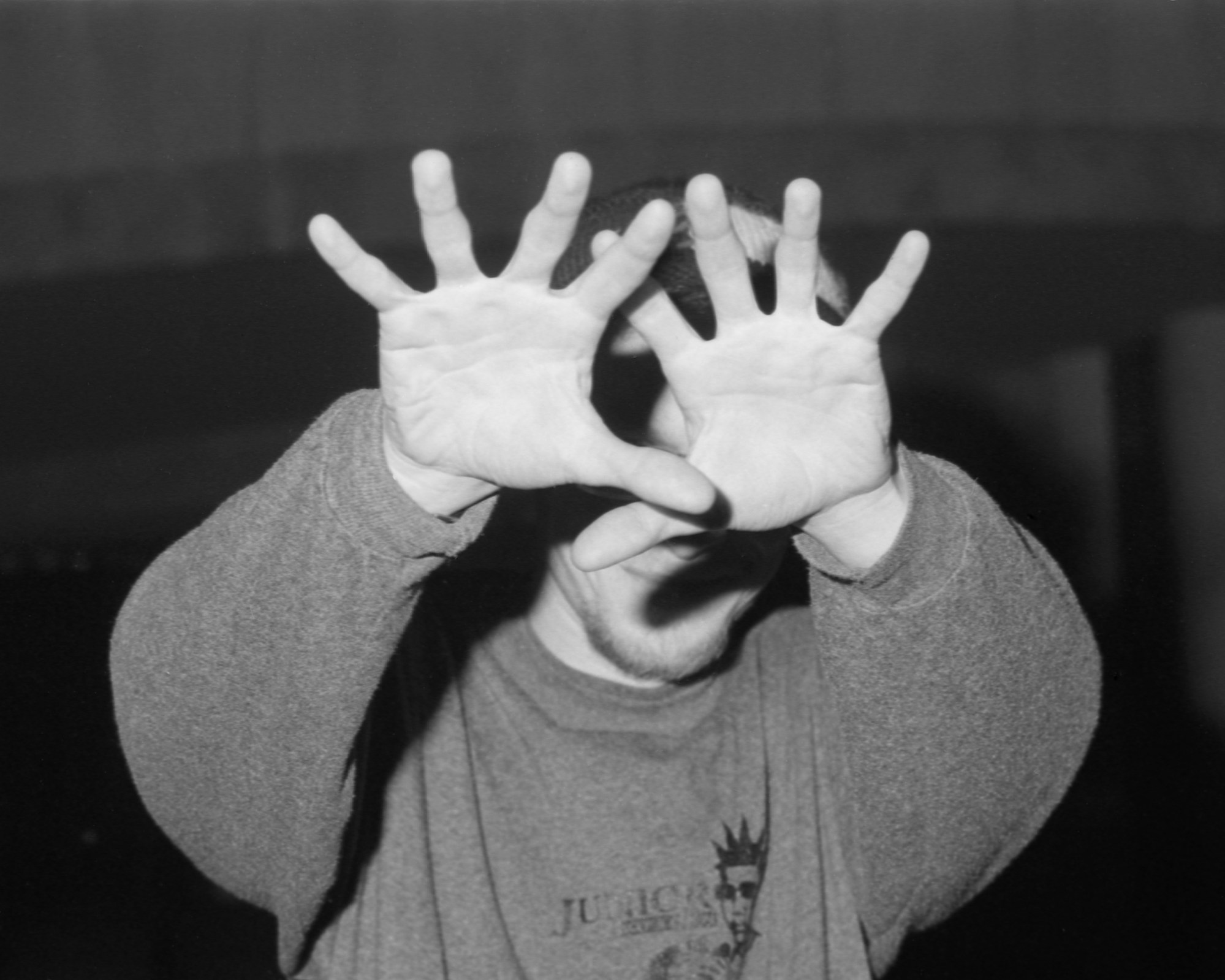

Within 24 hours, Richard D. James, aka Aphex Twin, was hospitalised with severe food poisoning. He spent the next few days recovering in a pokey, bleak room with a barred window; doctors did their best to help, administering mysterious injections that left him feeling even more befuddled. He was discharged, but still looked sick and was seemingly lost for words while interviewed by inquisitive Russian music journalists.

James’ puke-fest paled in comparison to that of Mark Pritchard, who subsequently became critically ill and was rushed to hospital after his intestines were attacked by a rare Giardia parasite. The long-term effects of this included serious damage to his stomach, as well as two years of related panic attacks and depression, before he gradually recovered. Pritchard continues to make music to this day, but was so traumatised by this experience he didn’t return to perform in Russia for another eighteen years.

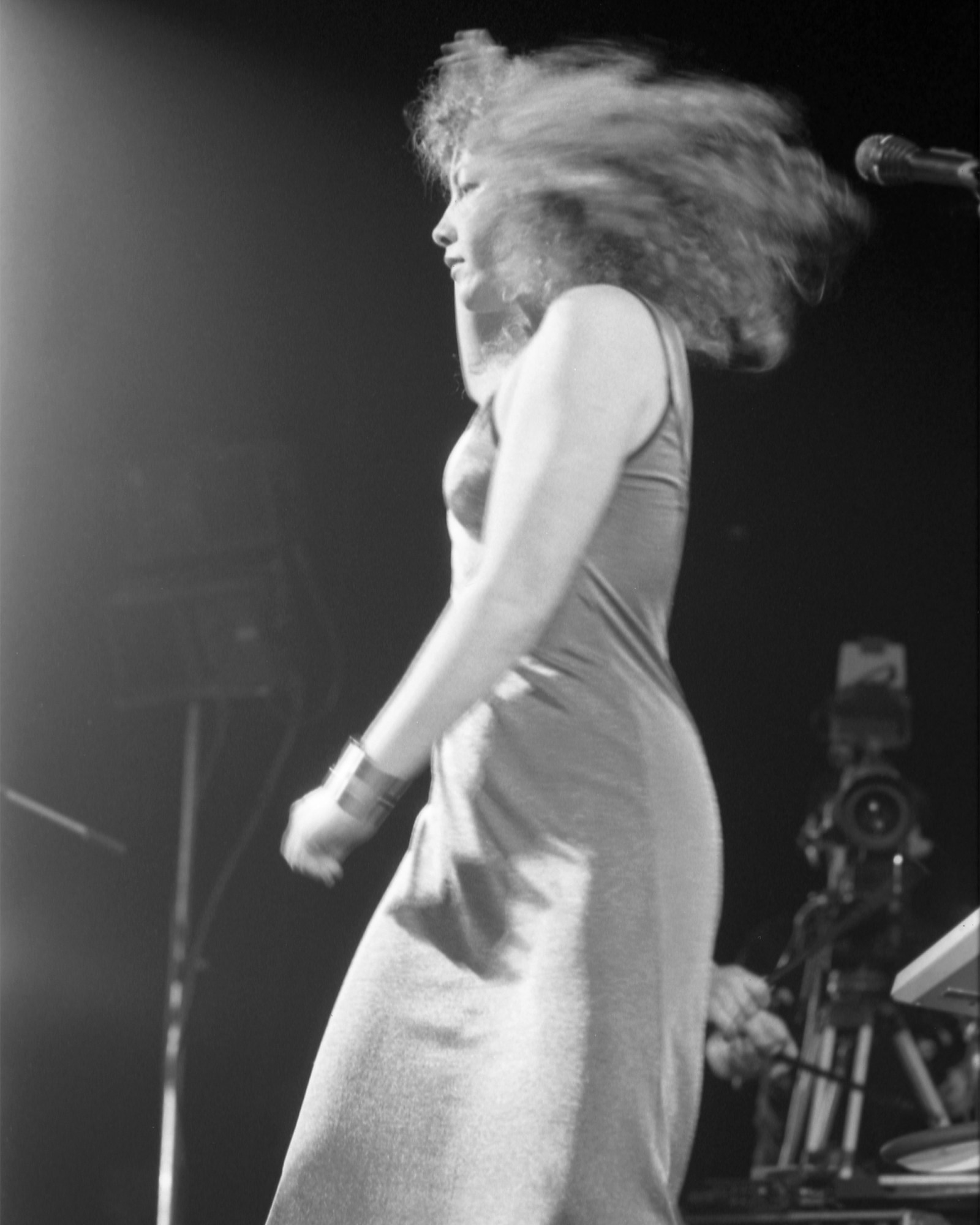

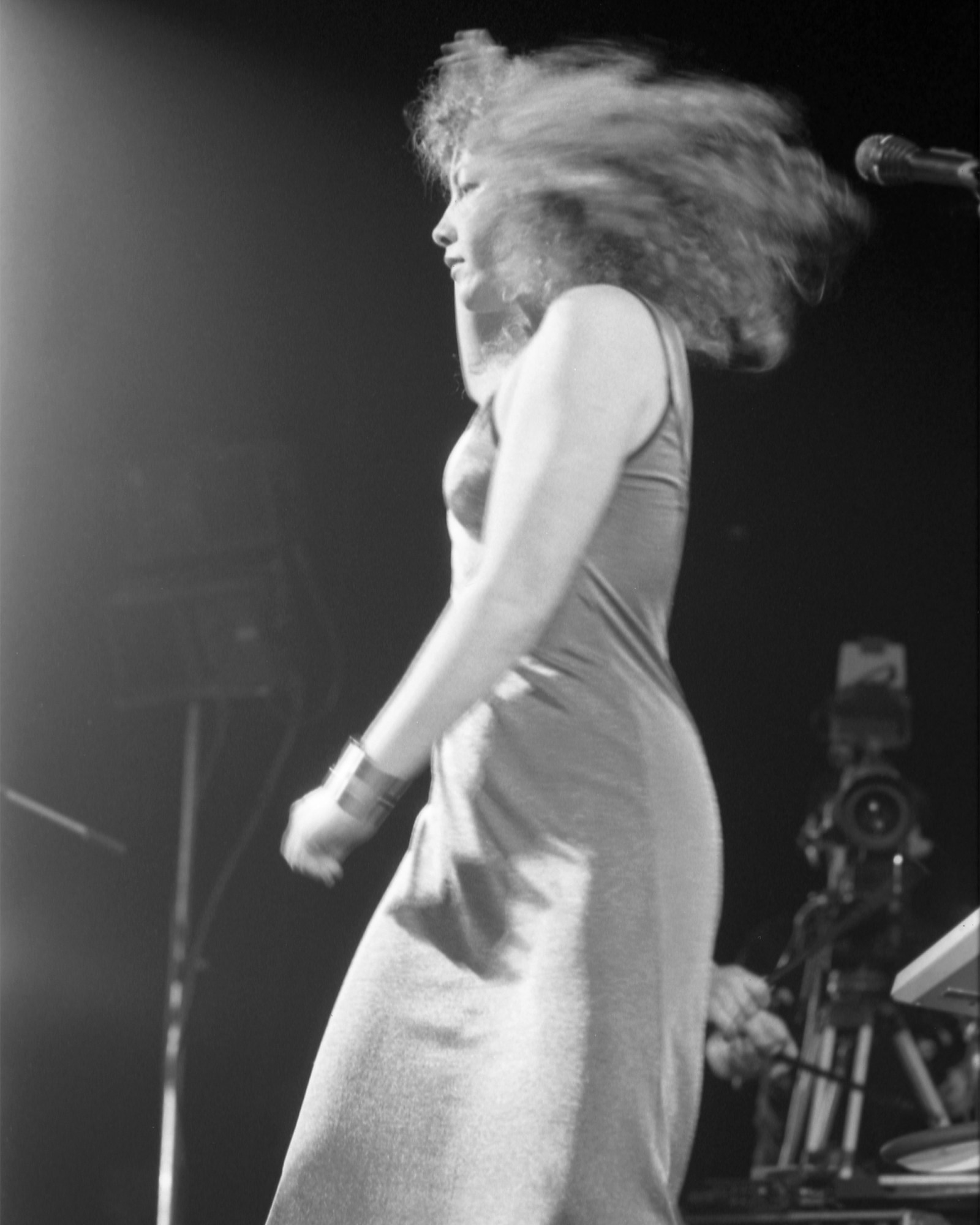

A variety of Britronica’s ensuing events were beset by other problems. Costly tickets plus an apparent lack of effective advertising meant that only a small crowd of revellers attended Dreadzone’s gig (featuring a young Alison Goldfrapp on vocals) at the Youth Palace, a vast 1,800-capacity venue. Ultramarine’s performance at a club named Pilot was similarly problematic: no PA equipment arrived until hours after the party had started. A startled Paul Oakenfold was elbowed off the decks by a local DJ who instead played chart fodder for another unwanted gangster clientele. At a different club named Jump, Alex Patterson waited around for two hours in the empty venue — which could hold over 1,000 people — before just a few dozen ravers suddenly turned up.

The chaos continued throughout the weekend. Semi-recovered from his hospital visit, Aphex Twin’s bleep-y DJ set failed to impress the venue’s manager, who had him dragged off stage at gunpoint by off-duty Russian soldiers temporarily hired as bouncers. Bark Psychosis’ gig at Pilot was suddenly cancelled by the management as their music was felt to be “too strange.” To top it off, a keyboard was even taken hostage at one point by disgruntled stage electricians who claimed they hadn’t been paid.

Despite these cock-ups, all the UK acts noticed the commitment and kindness of the clusters of music-loving youth whom — against the odds — travelled from far and wide to the events. Tickets for the Britronica events were selling for the equivalent of £10 each — more cash than most of the eager teens would have had per month. Despite this, some of them generously lent their decks and speakers to the Britronica artists to help them out when needed, or even brought them ready-rolled joints and shrooms.

Whenever they weren’t being dragged off stage or threatened by squaddies, the Brits snuck the youngsters into the gigs for free, showered them with merch, and treated these teensy but appreciative audiences to their finest sonic sojourns. They now remember these interactions fondly: “The people we met had it very tough but were also very warm, strong people,” remembers Pritchard.

“Most of them were young men with an existing interest in the electronic and rave scene,” says the music writer Rupert Howe, who at the time penned a gonzo, suitably vodka-soaked report of the Britronica experience for the NME. “One kid tried to get us to go to a rave in an old nuclear bunker near St Petersburg,” he recalls. Peacock, of Seafeel, remembers her interactions with the youth exposing how dire the situation in Russia was at the time: “We spoke at length with a guy called Igor who enlightened us about how hard life was there. The poverty and deprivation of ordinary people were a sobering shock.”

There were certainly some triumphant Britronica moments, and Seefeel also fared well with their atmospheric gig captured here. Howe’s NME report singled-out a great performance from Autechre, writing: ‘They come on in near-total darkness and let the machines do the talking, the hard-edged electronic rattles and squeaks smoothed out by rolling electro-style beats. At just the right moment, madness has arrived.’

Thirty years ago, during the rather hungover plane journey back to the UK, Britronica’s co-organiser Nick Hobbs accurately declared that “No-one out there will try anything like this again for a very long time.” A decade later, his co-promoter from the Russian side, Artemy Troitsky, poignantly revealed: “I’m often asked whether I had failures and mishaps in my life, whether I ever made serious professional mistakes. Then I usually tell a sad story… the festival Britronica with Aphex Twin, Autechre, The Orb and others that I organized in 1994 in Moscow. That festival was attended by one hundred people because nobody knew the participants at the time.”

In an article from 2017, the writer Katherine Rakitskaya, described Britronica, “a legendary failure” and “an unbelievable fiasco.” Pritchard is more measured: “The organisers, Artemy Troitsky and Nick Hobbs, were trying to do a good thing,” he says. “But it was just an impossible situation at the time.”

Britronica was an impressively ambitious adventure staged in the analogue age, without the promotional benefits of the internet and social media, in a country then-racked with poverty and strife. Not to mention that most of the participating artists were back then pretty obscure in Russia; radio airwaves were still largely dominated by mainstream rock, as opposed to white label vinyl imports from these early-90s’ talents. Indeed, the combined efforts of these brazen trailblazers encouraged an appreciation throughout Russia for future-facing music, that grew and endures nowadays at homegrown raves, festivals and clubs such as Signal, Popoff Kitchen, Arma and БАУНС. It just wasn’t the right time. Howe elaborates: “I think the intentions were absolutely sincere. But in terms of organisation, it was all over the place.”

Credits

Text: James Anderson

Photography: Steve Double / Camera Press