When Bruce Weber walked out the doors of a Richmond, Virginia jail this spring, he felt free. There to photograph a daddy/daughter dance organized for incarcerated fathers, it was one of those shoots where the emotional stakes were higher than high. A tiny universe removed from the celebrity portraits and fashion advertising that fill much of his life’s work in Miami, Montauk, and New York City. “It’s commonplace to us the idea that we can walk out of the office at the end of the day and have another life; they can’t have another life at that moment,” he says of the experience.

So how did one of our most glamorous photographers end up chronicling this little-known, formerly Confederate corner of the South? The story is one of many singular tales in this year’s edition of All-American, the arts journal that Weber somehow publishes annually in addition to shooting pretty much every campaign in the biz from Land’s End to Louis Vuitton, and celebrity magazine covers from Lady Gaga to Bill Murray. But Bruce’s humanity and curiosity extend far beyond fashion and glossies. So when his editors showed him a powerful TED talk with Angela Patton of Camp Diva, the organization for young women that organizes the prison dance, they began plotting a trip to Richmond.

The first Camp Diva community dance in Richmond was in 2012, with the goal of helping girls in Richmond get closer to their dads, on their own terms. However, the first dance revealed a devastating truth: many of these girls had dads who could not attend the dance, because they were in prison. So a second dance was born, in the Richmond jail. Bruce and his team traveled to Richmond in March of this year to capture both dances, the entire “Dance with Dad” weekend.

To participate in the prison dance, the fathers must be nonviolent offenders, and take part in a 14-week course in “New Beginnings of Fatherhood.” Many of the men profiled in Bruce’s story are locked up for drug-related offenses, in keeping with the devastating outcome of the ongoing American war on drugs.

The narrative quality inherent in the relationship was appealing to Bruce. “Fathers and daughters have always had a very close relationship in the history of families and writing for families,” he says. “And it’s wonderful to see these dads really try to connect with their daughters. I was just stunned by it and it was really great.”

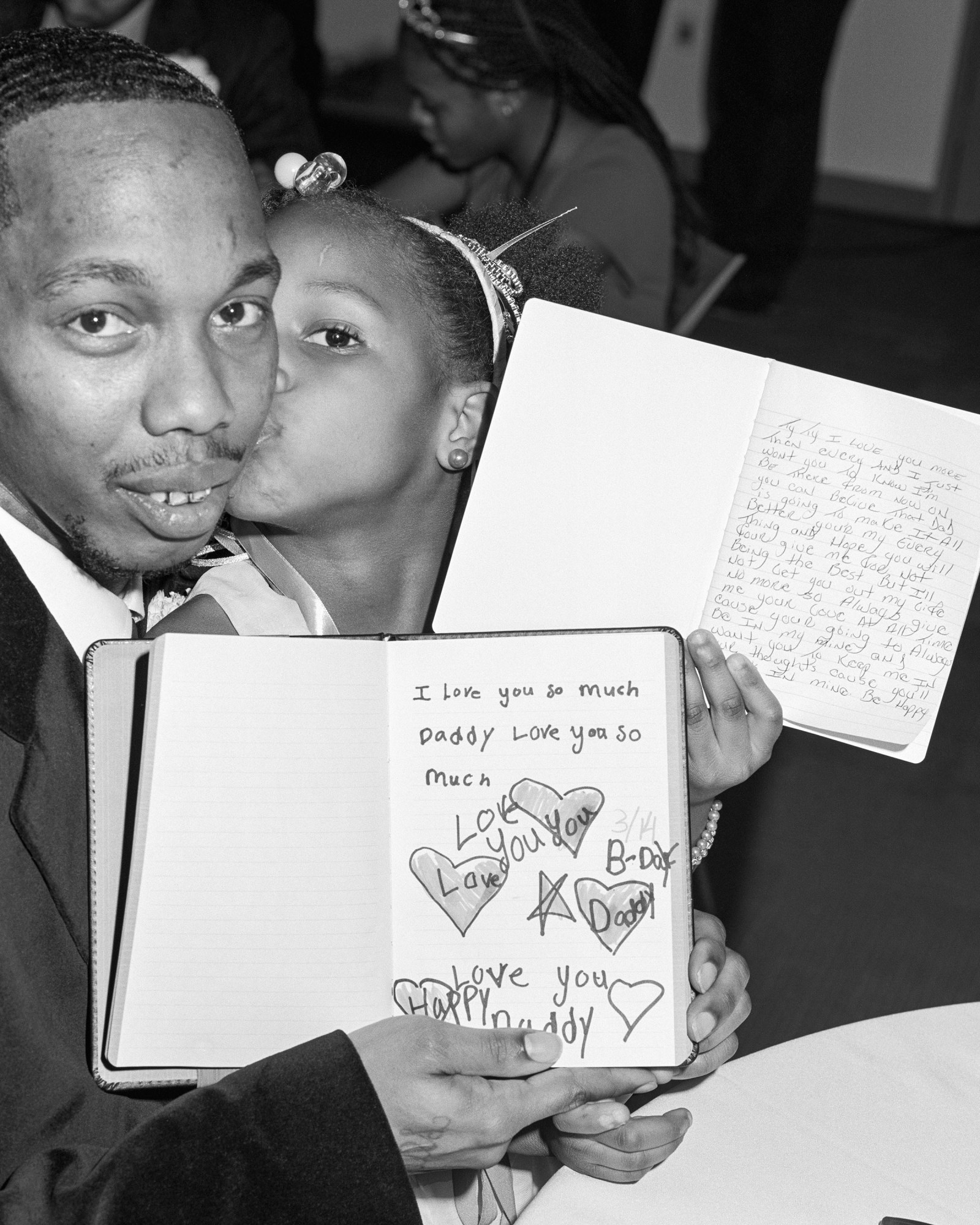

Characters emerge in the photos. We meet Tyshawn (above), the gold-toothed, tattooed charmer who grew up with an incarcerated mother and wants to create a more promising future for his daughter Ty Ty. We see smiling Ty Ty get ready for the dance, her grandmother tying bright pink ribbons in her hair.

As to what his time at the Richmond jail reveals about incarceration in general, Bruce hints at the hope hidden in cycles of despair. “I really feel that so many of these extraordinary men that I got to photograph really wanted to change, really wanted to be there for their kid and start a new life,” he says. “And it’s going to be hard. It’s really hard because of the neighborhood they have to live in. You know, truthfully, i think the thing that can be the biggest support for them is their church.” Or work. “I think that a job sometime saves you, and that’s something that I learned from this.”

Bruce could almost be talking about himself. Photography can be a means of experiencing unimaginable situations. But how does an artist use these images for good, without letting the emotion take over? Diane Arbus would talk to Bruce about how difficult it was to extricate herself from her suffering subjects; the Jewish Giant was always calling on the phone. “When I’m in a situation like that then it stays with me forever, and it’s hard not to really get involved after,” he says. “I hope that they get to see the photographs and the stories that we did so that in their lifetime they have a record of that moment. Maybe just seeing the beauty of their daughters and seeing the affection they had will keep them out of trouble.”

This wasn’t the first time Bruce had taken pictures in a prison. For a while he photographed a policeman in the Raleigh Prison. He also shot the Death Row in a Huntsville, Texas prison, the same one where Danny Lyons did his 1971 opus Conversations with the Dead. In Huntsville, he found himself distracted by the prisoner’s shiny shoes and perfectly fitting pants, then wondered if that was superficial. But that’s just the way Weber sees the world: its beauty continually folded unexpectedly into its pathos. As he says, “If you’re going to photograph, ever, it’s just going to be part of your life. The good, the bad and the ugly.”

All three were in full effect over the “Date with Dad” weekend. Bruce’s photographs show the transformation that took place when the jailed men changed from their jumpsuits into donated suits for the dance. Their posture changed; they stood a bit taller. “When they put their suits on one of the prisoners said to me, ‘Now I feel like a man.'”

The pageantry of dress-up is a focus of the film Bruce made at the dance for the larger Richmond community, premiering exclusively on i-D (below). Not to be confused with the prison dance, this event is open to everyone, and it has become a much-loved town fixture. Bruce filmed the arrivals to the dance, girls in frilly Easter dresses, white tights, and mary jane shoes, smiling widely next to their dapper, beaming dads.

There’s something valorizing about being seen, whether it’s a convict being seen by one of the world’s preeminent photographers, or a daughter being seen by her father. Of his subjects (all of them), Bruce says, “I believe in who they are as a person, because they shine for me.” These Richmond images fit into the larger theme of this year’s All-American book: ‘Leap of Faith,’ which includes many other stories of ordinary people doing extraordinary things. The family-run Noah’s Ark animal sanctuary; the war photographer Lynsey Addario; the Iowan painter Jane Wilson.

At the prison, part of the dance involves the fathers writing on hand mirrors, You are so beautiful, and holding them up to their daughters’ faces. Which is not so far from Bruce’s intention with this project, and with all the pictures he takes. As he says, “If we had to put a little insert in the book I would say it was a picture of holding up a mirror and saying, ‘You are so beautiful.'”

Credits

Text Rory Satran

All images (c) Bruce Weber

Thanks to Little Bear Studios