Bucharest is hard to get into. On a Friday afternoon, like the one I arrived, traffic snarls and the trip from the airport to the city center can take more than an hour. Your cab moves only a bit faster than you could walk, offering a slow tour of the city’s motley architecture: grand Beaux-Arts apartment buildings beside Art Deco and postwar prefab modernism. The most distinctive buildings are Romanian Revival, the eclectic nationalist style of the city’s fin-de-siècle glory days, featuring vegetal ornament, rectangular massing, and kokoshnik arches—a hodgepodge within a hodgepodge, chaotically combining neoclassical, early modernist, Ottoman, and vernacular elements. The contrasts make for a romantic streetscape of dilapidated grandeur, united primarily by facades of peeling plaster, Paris-style street signs (Bucharest used to be known as the “Paris of the East”), and riots of iron twisted to form grand gates, fences, and balustrades. It all feels very Nosferatu.

I was there for Bucharest Fashion Week, the latest in the Mercedes-Benz calendar that also includes Berlin, Madrid, New York, Miami, Istanbul, and Mexico City. Now in its second year, the event signals the arrival of the Romanian capital within the roster of sartorial destinations, bringing both capital and attention to the city. But for someone more familiar with Paris and Milan’s semiannual orgies of expensive clothing scattered around cities whose taxi drivers are ill-equipped to get you to the catwalk on time, Bucharest’s Fashion Week felt almost sustainable: the majority of shows shared a single location.

Specifically, Bucharest Fashion Week unfolded primarily in the central wing of the former Royal Palace of Bucharest, a monumental building in the center of the city that witnessed the arrest of pro-Nazi Marshal Ion Antonescu in 1944 during the coup by the Allied-aligned King Michael. The Luftwaffe bombed the building in retaliation; it was hastily repaired by the Soviets and then, following the Communist revolution, became the Hall of the State Council, where subsequent leaders, notably Nicolae Ceaușescu, turned it into a backdrop for various political events.

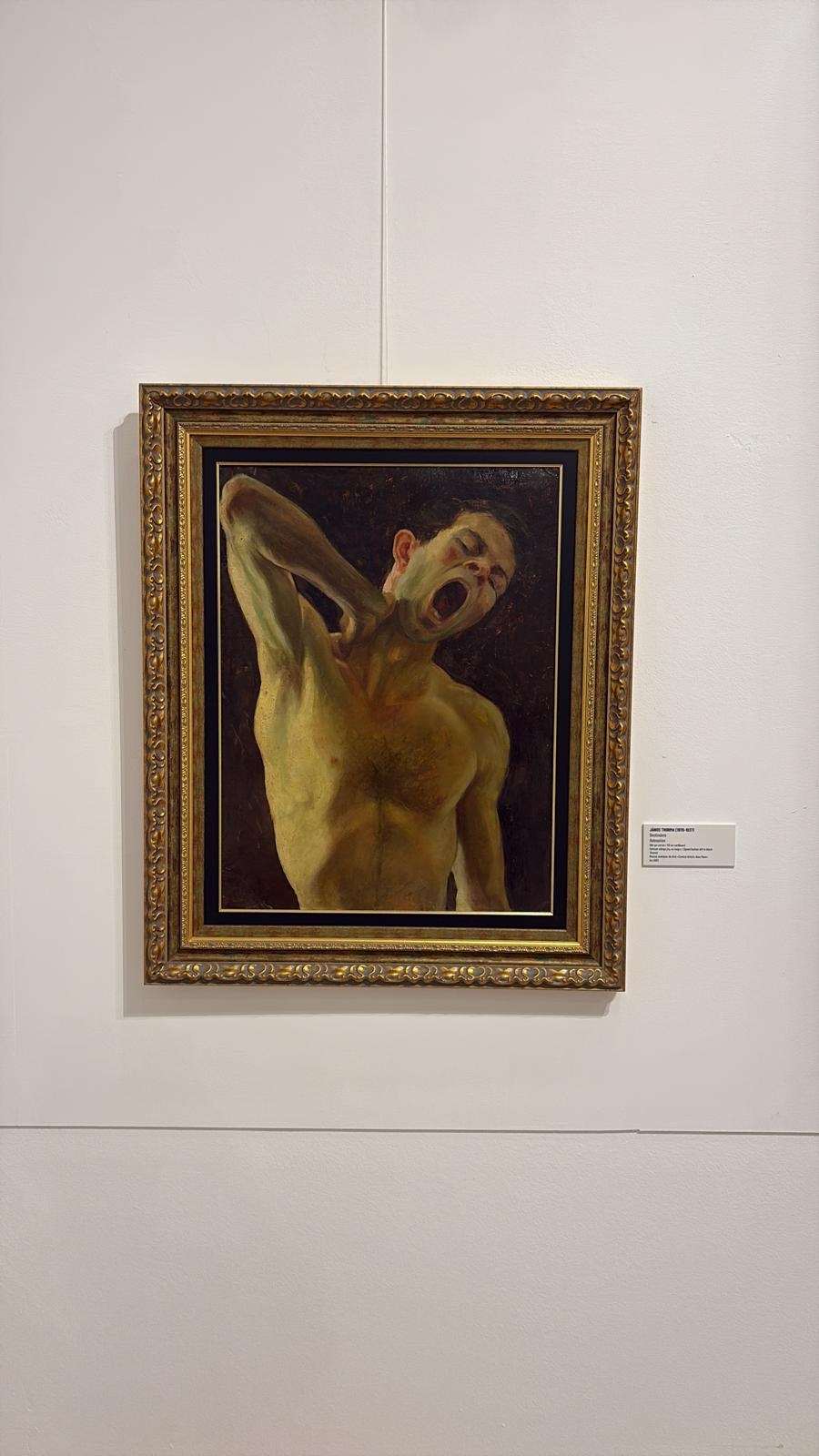

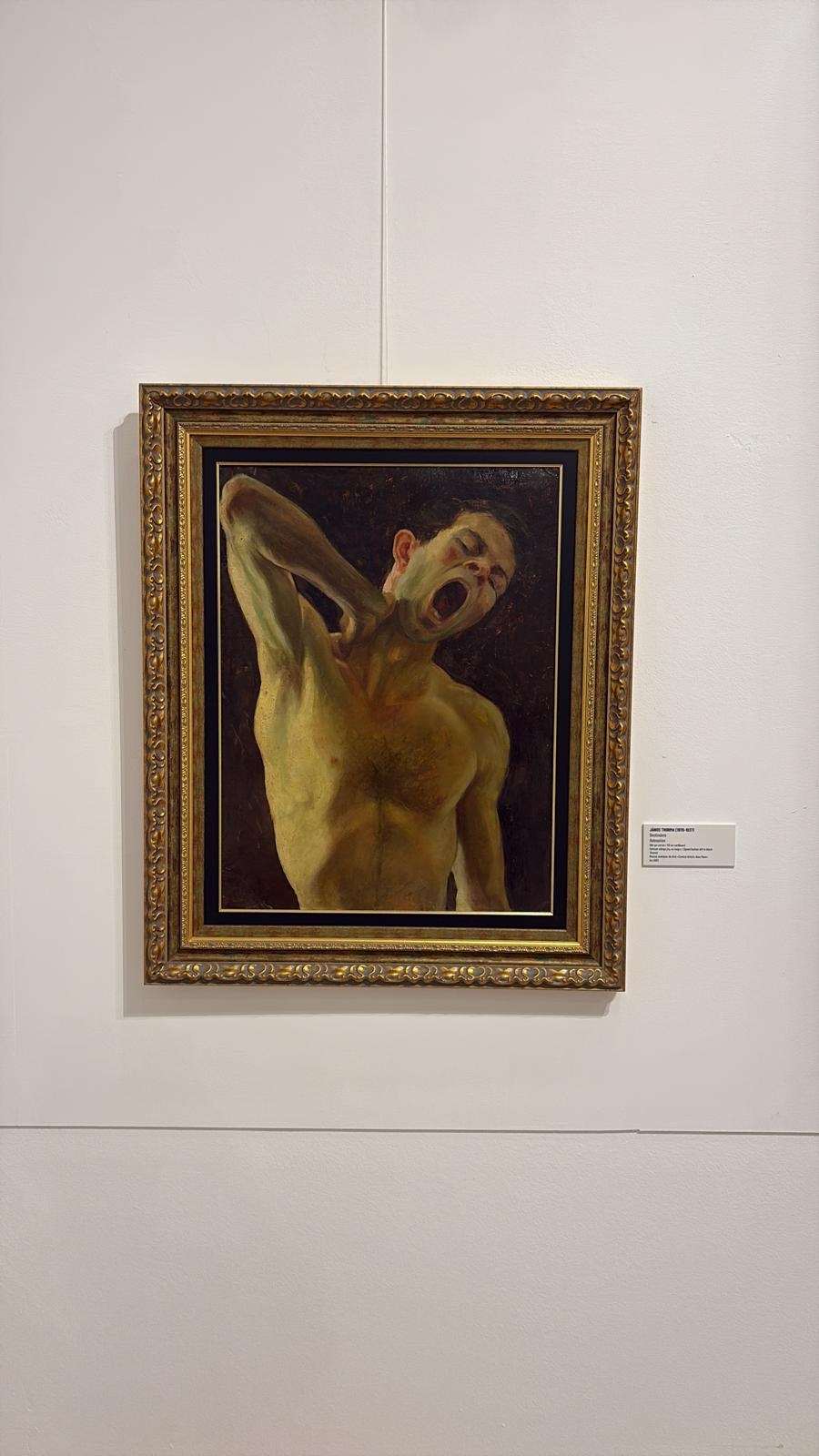

Today, its marble interiors are illuminated brightly by an excess of fluorescent bulbs. On the weekend I visited, the basement of the left wing housed a temporary exhibition featuring facsimiles of costumes designed by Constantin Brâncuși for the Ballets Russes, while the right wing contained, undisturbed, the National Museum of Art—a magnificent collection of works spanning medieval Orthodox icons to modernist masterworks, strewn across six floors that the stray visitor has almost entirely to themselves. Sandwiched between the two, the Fashion Week headquarters made for odd luncheon meat, relished with an eccentric collection of attendees. At other fashion weeks, the norm is to wear clothes by the designer whose new collection you’ll be seeing—or at least something fairly subdued. In Bucharest, black leather and fur stood incongruously next to voluptuous peasant dresses festooned with bows and pearls. It was as if every edgy trend of today had been typecast and assigned a position smoking in front of the venue entrance.

Inside, the chaos intensified. Various branded booths offered spritzes, coffees, and step-and-repeats. In the next room, a giant LED screen broadcast interviews that were being filmed live in the same space, including one in which this author found himself unwittingly participating. Pushing forward, through the crowd and up a grand marble staircase, you entered the main—or rather singular—catwalk of Bucharest Fashion Week: a carpeted space with non-hierarchical seating (everyone was front row). Shared among all designers, whose primary means of atmospheric differentiation was sound design, the effect was democratizing—refreshing, even. You found yourself looking at the clothes, not the sets.

The collections themselves were all over the place, both aesthetically and qualitatively. A standout was Carmen Secareanu, a legend within the Romanian fashion scene. A soundscape of buzzing flies lent a macabre twist to a collection that featured dress shirts reconfigured into skirts and sheer fabrics with delicate embroidery. At one point, a woman seated diagonally across from me took off her shoes and danced elegantly down the runway. Another attendee confirmed after the fact that this was not a guerrilla intervention.

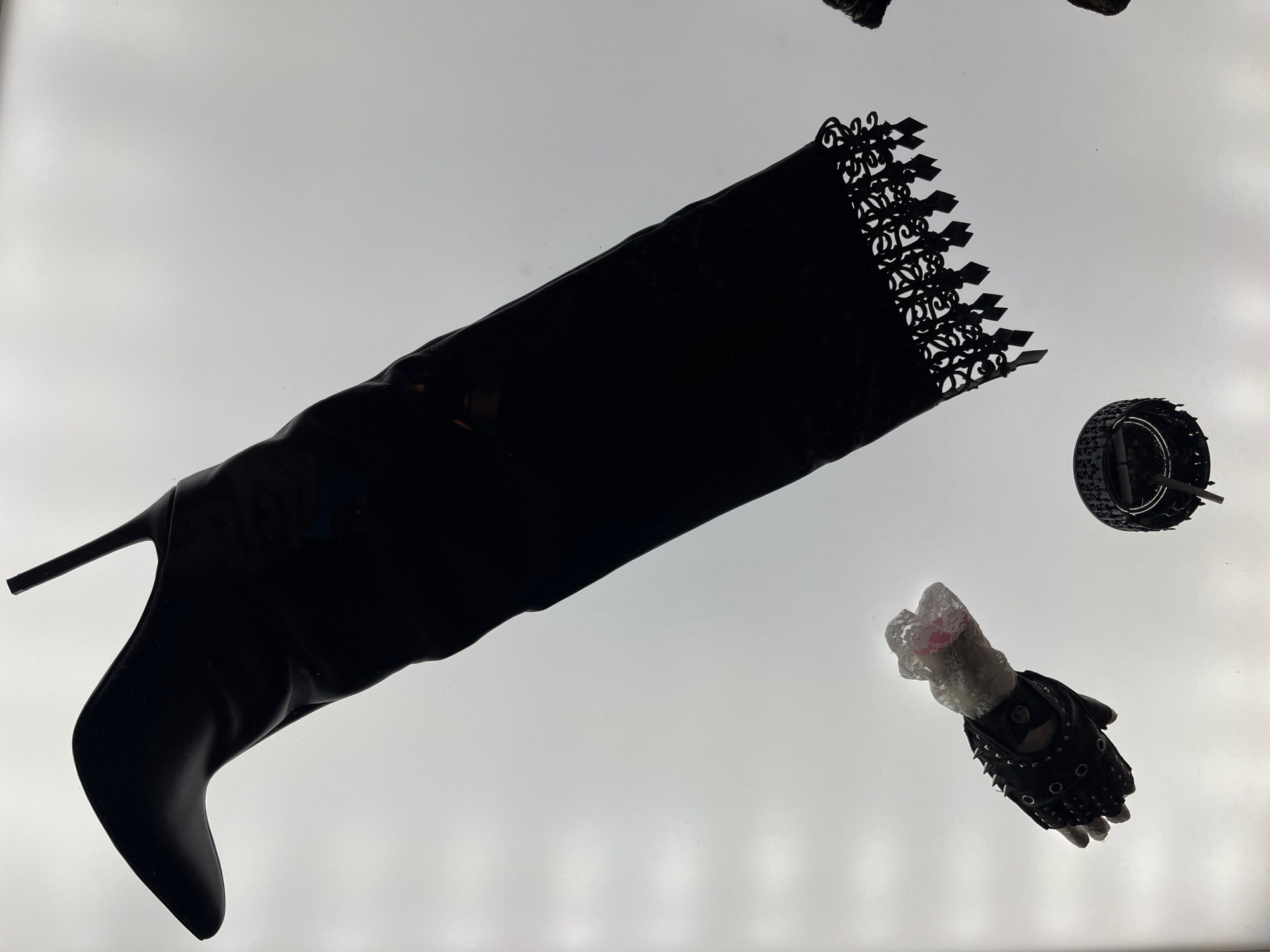

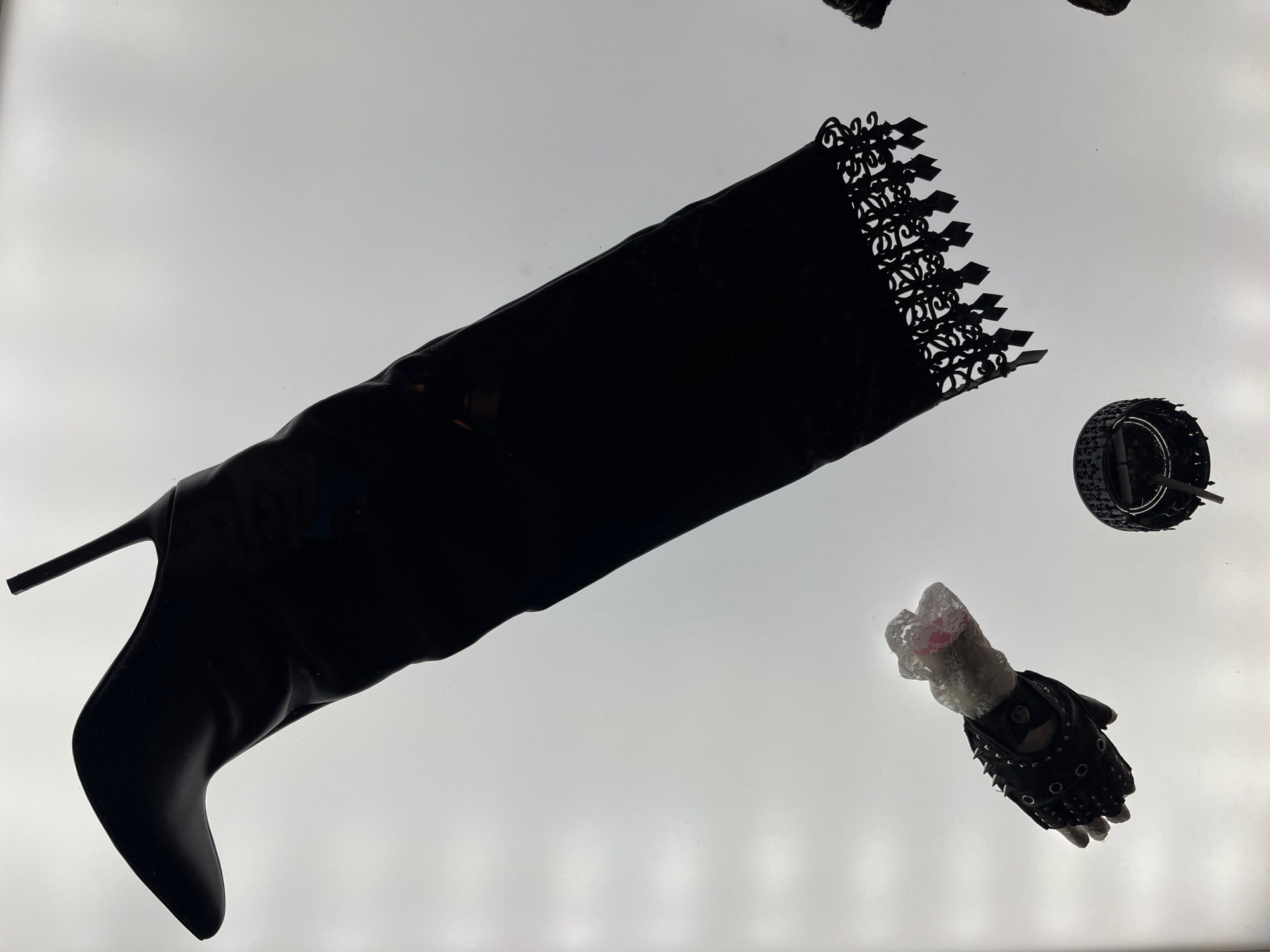

While concentrated, Bucharest Fashion Week still had its share of side events. A 10-minute walk from the National Museum was the exhibition MRACONIA. Held in the Filipescu-Cesianu House, an aristocratic mansion that had been converted into a Chinese restaurant in the later years of the Ceaușescu regime, the building is now primarily a ruin. On the night of the opening, its grand facade was illuminated red. Inside, the debut collection of the brand BALKAN, founded by the young creative duo Stefan Dragic and Vasilis Marlantis, was on display. The collection featured leather bags encased in delicate metal cages—miniatures of the grand iron gates found throughout the Romanian capital. These were 3D printed rather than cast—otherwise the weight would be too much to carry. Beside them were previews of a ready-to-wear collection featuring similar motifs: leather gloves with the tops cut to resemble ironwork spears and silk scarves made in collaboration with the Greek graphic designer Korina Gallika. On the walls were still-life paintings by the young Romanian painter Lucian Pruna, rendered in soft classical strokes but depicting tobacco pouches and plastic takeout bags. Ceramics and a large-scale actual wrought-iron gate converted into a speaker system—also by BALKAN—completed the scene.

The debut was something of a graduation ceremony for Dragic and Marlantis, who act as nodes within the Bucharest scene. The former founded Bullseye and the latter Project Symposium, both well-known streetwear brands in the city. With BALKAN, whose bags are proudly marked “MADE IN ROMANIA” but clearly oriented toward a pan-European market, the claim-turned-tagline of Marlantis’s former label—“East is the new West”—feels closer to realization. Streetwear has a tendency to flatten regional differences, but here the young designers were flaunting them. Rather than eschew the vampire fantasies that their city and region are associated with, they dramatized them.

The philosopher Slavoj Žižek has described the Balkans as a sort of non-place—not so much a designation of the geographic peninsula as an always-exonymic description of elsewhere, an accusation thrown by Western and Central Europeans at whoever appears to them as their Other. Marked by communism and then a decade of sectarian war, the Balkans is seen as a “vortex of ethnic passion” and “a multiculturalist dream turned into a nightmare.” But as Bucharest Fashion Week seemed to make clear, difference is generative. Rather than assimilating into the norms that tend to render one fashion week all but indistinguishable from the next, the Bucharest fashion scene has met its own canonization by Mercedes-Benz with a refreshing confidence—a pride in place. Romanian hybridity, with more than a dash of spooky, slightly campy Transylvanian goth, proves fertile ground for a maturing scene that shows itself capable of being both European and still beautifully, inscrutably Balkan.