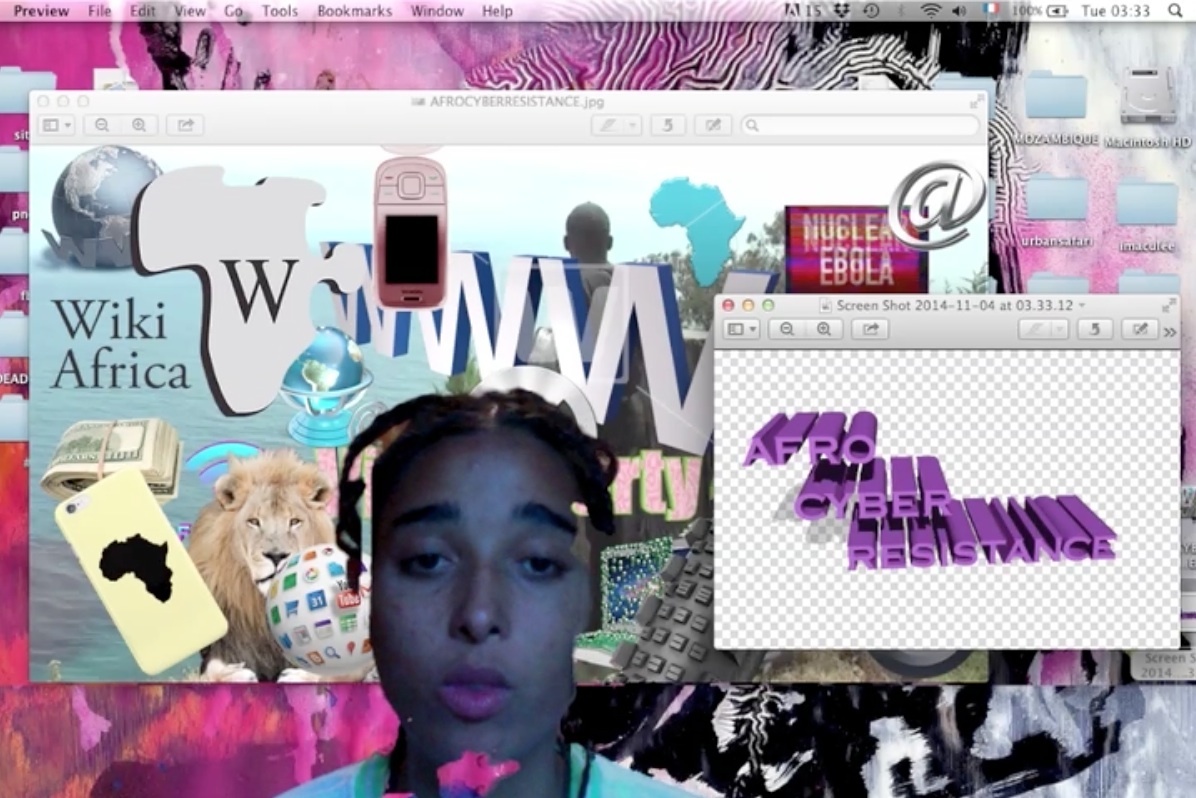

Is the internet a colonized space? This is the question artist Tabita Rezaire confronts her audience with at the beginning of her video Afro Cyber Resistance. As a white person, it’s a question I’d never considered before. We usually think of the internet as a politically neutral space, a digital democracy in which anyone with a Twitter account can participate.

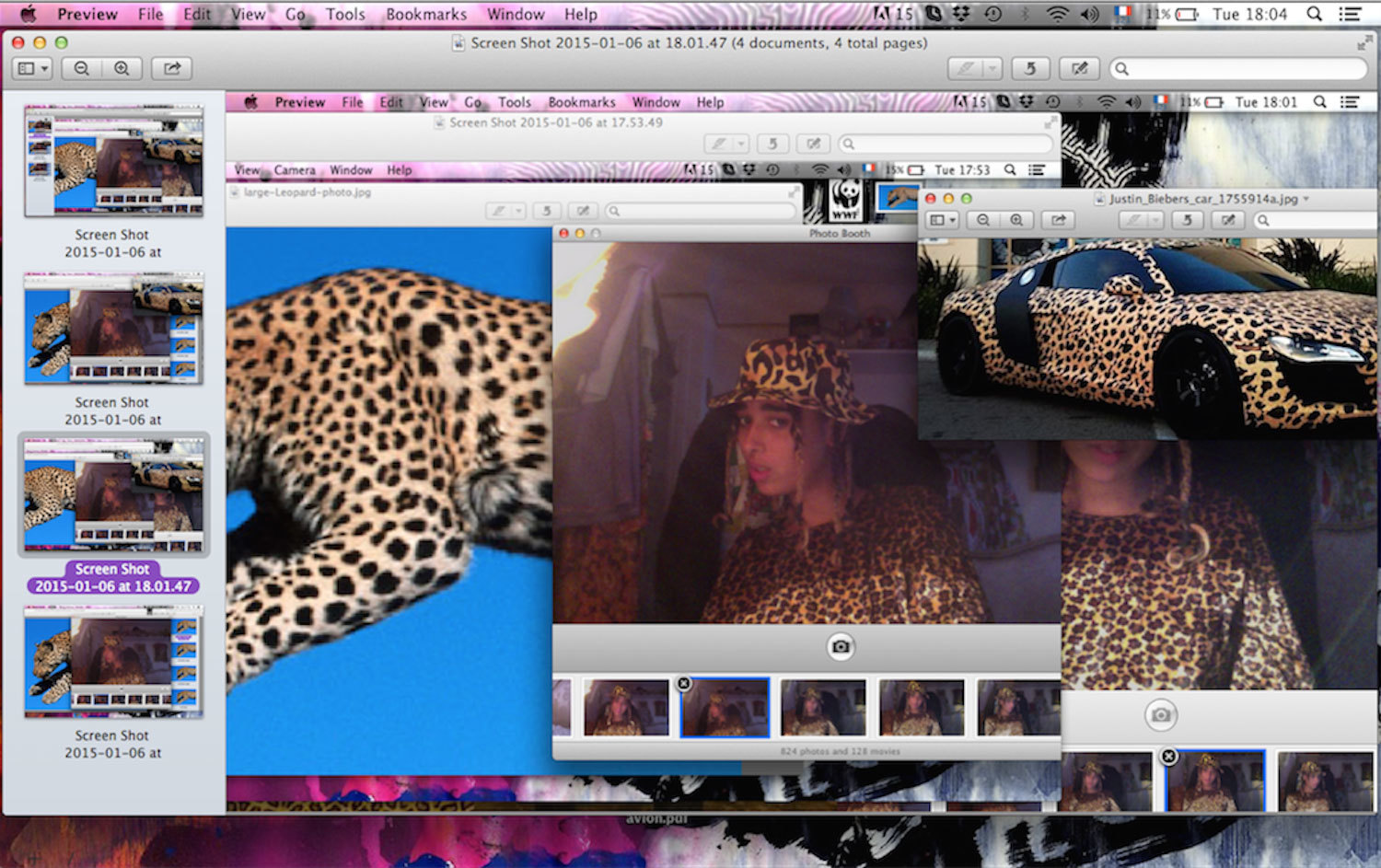

It is this preconception of the internet as non-hierarchical and open which is what Tabita challenges in her work. Whether it’s a video about the politics of twerking or a screenshot-collage about Photoshop skin-bleaching, the ugly truth which emerges is that the internet is a pretty racist place. Tabita isn’t talking about the odd 4chan troll, but about broader digital structures: representation of marginal identities on legitimised spaces like search engines and Wikipedia reveal that cyberspace itself is often governed by neo-colonial attitudes. Oppressions exist both online and IRL- and so, according to Tabita, it’s crucial that they are challenged on both fronts.

As someone who makes internet art with a clear political agenda, could you explain how the internet is a site of resistance?

Well, the internet is a space for sharing and disseminating information. And whoever controls this flow of information has power. So in that sense, the internet may be a space for resistance because we can participate in this exchange of information; the internet allows people to share alternative histories and narratives that are not represented in the mainstream. It’s easy to express yourself and upload your shit.

At the same time, I don’t buy the whole story about the internet being this democratic space. Only 40% of the whole world is connected to the internet, you know. The internet is a place of privilege, it has its class divides, it doesn’t embrace diversity. We think of it as this supposedly democratic utopian space where people can challenge oppressive systems, and at the moment it’s not. But we’re trying to change that.

And these internet power structures is the subject of your video Afro Cyber Resistance. How is the internet a colonized space?

I’m very interested in the colonial nature of power. Colonialism enforces a hierarchy between people, and between races, and the internet mirrors these structures, because it’s controlled by Western multinational corporations like Google and Facebook. If you want to see how it’s a colonized space, just look at Google. Search for images of black men and the black male body and you have these half naked muscular black guys, sexualizing the black male body, reproducing traditional, racist representations. And if you do the same for the white male body you have all these guys with their shirt on.

You often find that black bodies and black narratives are totally erased on the internet. An example is the representation of dreadlocks, which is primarily a black hairstyle. But if you type in ‘dreadlocks’ on Google images, its only white people wearing dreadlocks! It’s crazy.

You say the web’s not this global, abstract space and that our experience of the web differs depending on our physical location. How does Johannesburg influence you, online and IRL?

Sometimes being in Johannesburg makes me fucking angry. But at the same time it’s an exciting space to be in because there’s stuff to be done politically. What I mean is that everything is very racialized, and in-your-face. You can’t escape from your race here. So it made me more of a radical, in terms of questioning these power structures. My interest has always been in body politics, but I became more interested particularly in race and body politics.

In terms of internet usage, I’m now much more aware how the internet is a really privileged platform. I grew up in the West, so I’ve had high-speed internet since the 90s, and I came here and it’s so slow. But it makes you put internet use into context. Now, only around 40% of South Africans have access to the internet, and of these just 10% have internet at home. The digital divide between North and South is very real, and moving to Johannesburg definitely made me more aware of it. And this inequality in access explains the inequality of content. It’s almost like a unilateral flow of information from up there at the top, which we just consume. And you know, we have to put content up there ourselves. Which is what I’m trying to do.

Your work is made of internet debris: you sort of take apart the internet and put it back together again. Do you consider your work as hacking?

I think of hacking more as coding and infiltrating formal systems. I’d say that my activism is more about visual resistance. I don’t hack websites and governmental agencies – not yet anyway! My work is more about claiming spaces and trying to be visible and loud on the internet. They’re kind of different strategies.

Do you see other people making work with a similar political agenda to yours? Do you feel as though you’re part of a movement?

Sure. I wouldn’t say it’s exactly a “movement”; we don’t have a manifesto or anything. But definitely, there are a lot of projects happening at the moment that focus on brown people and black artists on the internet. And these are often intended for a black audience or a black readership. The internet has created loads of great communities and safe spaces for people to share their work.

Credits

Text Niamh McIntyre

Photography Tabita Rezaire