The early pages of Campbell Addy’s new monograph reflect a rare level of critical acclaim. Feeling Seen, which will be released this April, features a broad selection of commissioned fashion photographs mixed with his signature portraiture; alongside words and reflections from friends, family, and figures like Tyler the Creator, Edward Enninful — one of Campbell’s mentors, who contributed a foreword — and Naomi Campbell, whom he’s photographed multiple times.

Naomi’s quote expands on a tweet she posted in 2019, after sitting for portraits with him that would cover The Guardian’s Weekend magazine. “It’s my first time in thirty-three and a half years shooting with a black photographer in mainstream fashion,” she wrote. She layers additional context into the book, recalling that the British Fashion Council award she won a few weeks later was also the first time she felt seen by her industry in the UK. For her, “that night was a double honour,” because Campbell also received a British Fashion Award — his second in as many years — naming him one of the BFC’s ‘New Wave: Creatives’.

Campbell’s ascension, since his start launching Nii Journal — an independent fashion magazine that ultimately evolved into an agency — has transformed him into one of the fashion industry’s most influential photographers. An insatiable work ethic locked him in full-tilt, consistently booking jobs with the world’s top models and celebrities for publications including WSJ, Vogue Italia and of course, i-D.

Speaking on his feeling about awards and the complicated notion of success, Campbell admits over Zoom that while, “I can understand it and I can comprehend it”, he can’t “touch and smell it”. The intangible satisfaction of external validation isn’t what he’s really chasing; he’s fundamentally driven by a visceral need to express himself. “I didn’t want to get caught up in the rat race, in the wheel of success; especially in an industry like ours,” he explains. “I’d just be chasing manmade objects, instead of ideas. If I start assessing everything as something that can be calculated, I’ll end up turning it into an algorithm, as opposed to feeling it.”

It’s no surprise, then, that he’s disinterested in the media packaging that often surrounds his work and that of his contemporaries; fellow Black photographers like Quill Lemons, or his close friend Tyler Mitchell. Finding that the focus on a “New Black Vanguard” movement can sometimes feel disingenuous when placed in the wrong hands, he emphasises that his bonds with individuals in his close community, no matter how well-known they may be, are based on genuine connection and the creative “exchange of information”, as he calls it, not corporate or commercial interest in Black artists. “When we hang out, we talk about K-pop, or boys, or about this new movie or this new song,” Campbell says. Their conversations, as with any real friendship, are about survival by way of belonging.

“There’s always a flux and a friction to be the first of anything — it’s bittersweet,” Campbell observes, reflecting on representation in fashion and the crucial role of technology in creating space for inclusivity. He laments the fact that these resources weren’t as readily available to the figures who paved the way for him. “I’m very blessed to have been born in the age of such information. I can’t imagine if I was Andre [Leon Talley] or Edward [Enninful], or people that you can count on your hands, you know. There was no Instagram. To be connected, and exchange information must have been so much more difficult.”

Further into the monograph, in a transcribed conversation, esteemed curator and journalist Ekow Eshun asks Campbell what led to his choice of title. “I thought back to when I was 16, when I’d left home and had chosen to do photography,” Campbell responds. “It was because I couldn’t see myself anywhere. So, I knew that if I wanted to see myself, I had to have gumption. But what is the essence of feeling seen? In theory, my work is about showcasing. It’s about putting things within my world under the microscope. My book is about feeling seen because every person, every object, needs to be handled with care.”

It took, Campbell tells us, revisiting his entire archive to really begin to understand his own message and journey up to this point. Both arise out of what he calls “the exploration phase” and a desire to be “a vessel for change”. Moving forward, he’s thinking about the next step, and developing a new mission statement.

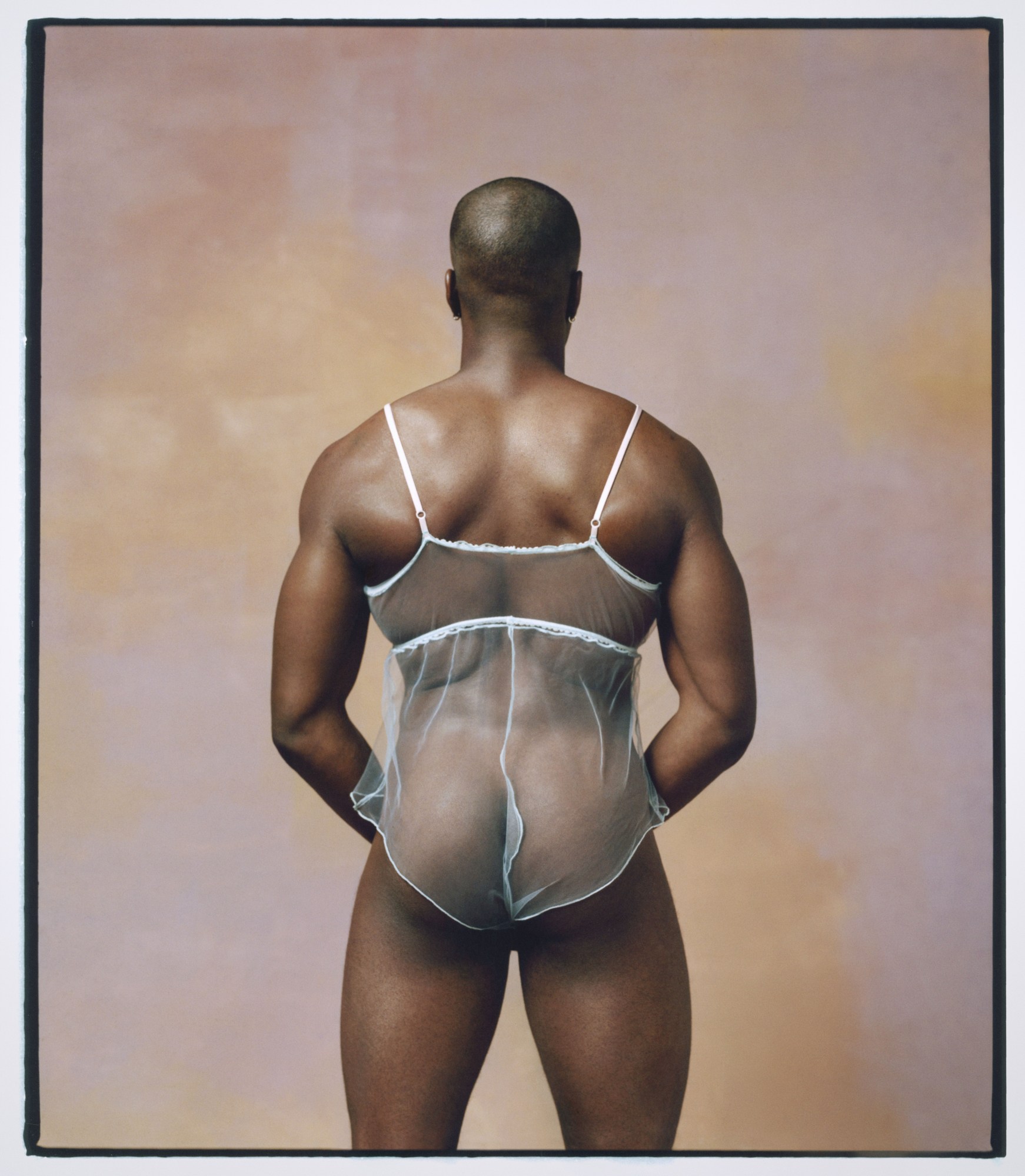

“We’ve done exploration now. It’s like, okay, this is what we’re going to do to start building,” he continues. “I’ve explored so much, but I’ve subdued a lot as well. I kind of want to go glam rock. I just want to go full camp. In terms of like, more is more is more. I feel like, as a Black man who is queer and was raised Jehovah’s Witness, there were so many boxes of restriction. Let’s just go one hundred percent this year.”

To Campbell, one hundred percent means world-building (both creatively and physically), and taking full control in a new chapter focused on “more self-directed work, at a slower pace”. He dreams out loud about a scenario in which every Black person working in fashion takes two months off to go to Nigeria, or Ghana — his ancestral homeland — to rest and recuperate in preparation for a creative uprising. “As Black people, we’re so spiritually inclined to do things, and yet we don’t own all the things we’re doing them for. And that’s where I think we’re getting into focusing more on self.”

A defining juncture in Campbell’s own exploration phase involved returning to Ghana this time last year, where he took a number of photographs featured in the book. “I wanted something new, you know, something to springboard me to the next section of my life,” he says. And so he went on a very long walk, snapping photos along the way. “I turned 28 there, and I went missing for a couple of hours. Honestly, I feel like I went on a spiritual journey because I don’t know where I went. No one else knows where I went, and I woke up at home. It’s not like the West — getting home is not easy,” he explains, laughing.

Recognising that time period marked the beginning of his first Saturn return, an astrological period some regard as a cosmic end of adolescence and entry into adulthood, Campbell describes the walk as an existential experience. He explains experiencing a sense of alignment with his ancestors, a strange but familiar feeling of connection with all Black people at once. “These pictures, for me, are almost like a reset, or a closing. I started my photography career going to Ghana, doing Nii Journal.” Some of those images from that first trip have also made it into the book. “Six years later, I went back. It’s nice to have that timeline. I’ve gone back to places I went before and it’s just, changed. Some places were anthills — now, it’s a metropolis.”

“Feeling Seen” is now available for pre-order until its official release on April 15.