About two years ago, the Los Angeles-based photographer Luke Austin started culling together imagery from his portfolio for a new project. In response to images in mass media depicting police brutality, mugshots, and a variety of other stigmatizing visuals, and a disparity he noticed on his Instagram feed which features his own work, he began on his second full length book of photography. This month, that book, titled LÉWÀ, a 148-page work composed of almost 100 shots of black men including the likes of actor Ashton Sanders, model Shaun Ross, model Yves Mathieu, and more, made its debut. But as a white Australian man, publishing a book of his own images of black men as a bid for their representation, the release, and Austin’s promotion of it, has kicked up a complex conversation about representation, ownership and the correct way to be an ally.

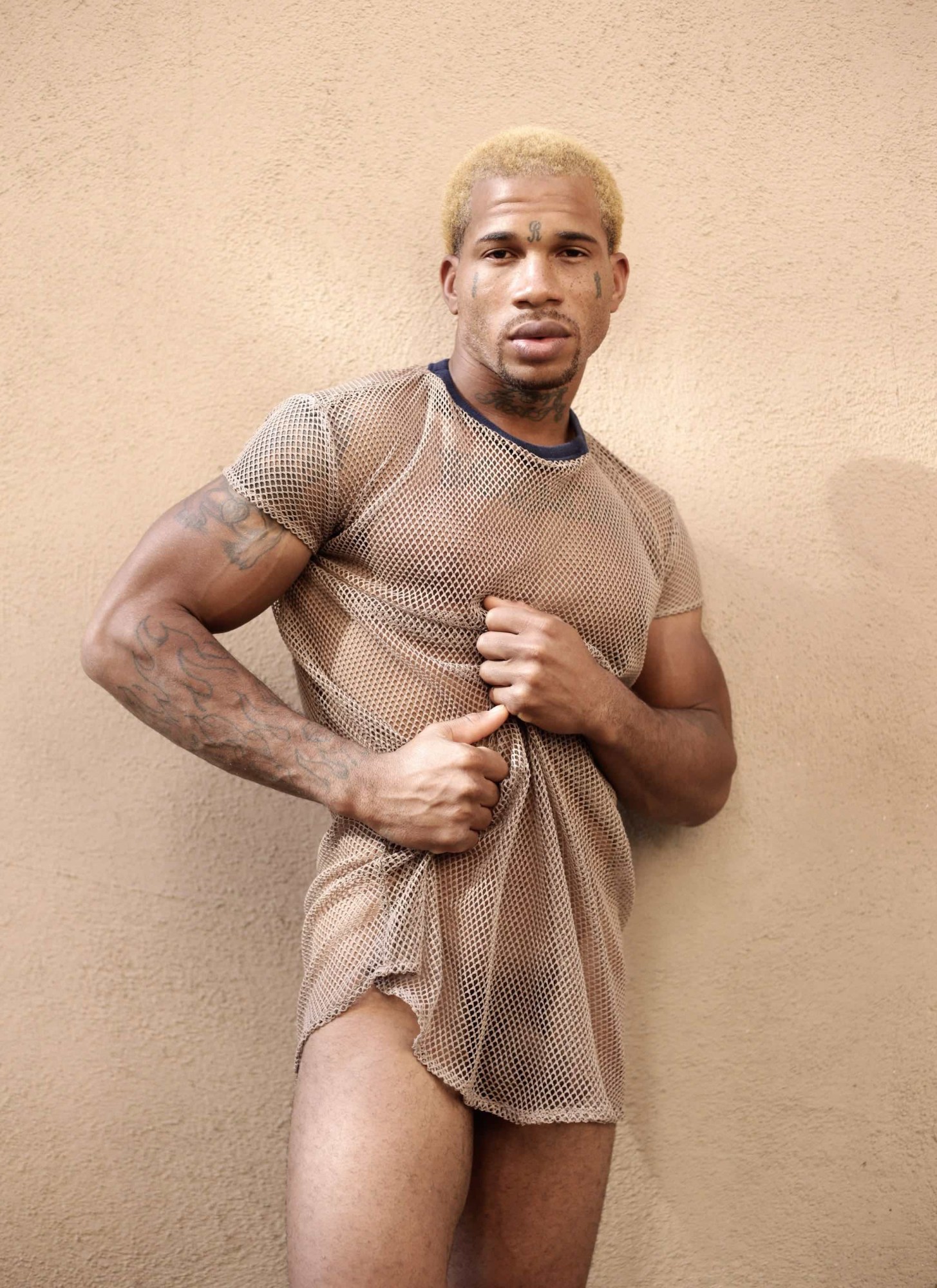

“I decided to put my favorite portraits of black men together about two years ago because it was a time where I was really noticing on Instagram, the different reactions that portraits of white men would get when compared to people of color,” Austin told i-D in a phone interview last week. In particular, his photos of black men were getting much fewer likes. “It was also at a time where a lot of young black men were being killed by police and it felt like that was in the media every day. So it was just a time where I thought this should all be put in one collection.” To do so, he culled together images he had already taken and shot a selection of new imagery. The full book spans five years, done in Austin’s trademark style: generally nude, boyish subject shot minimally and sensually against soft colored backdrops.

“The book isn’t necessarily for black men or for the people in the book,” Austin clarifies. “Sure a lot of people of color are loving it but it’s more for my white audience as sort of me shaking them or punching them in the face, kind of going ‘look at this,’ ‘do you not see the beauty here because you seem to be skimming past it on my Instagram.’” It’s a weird onus to start a project from and the Sydney, Australia native acknowledges as such in his introduction.

“The aim of the whole thing was to change those people that will flick through my page and double tap on every pair of white abs that they see but flick past any person of color,” Austin said.

“This felt like an opportunity to really have a conversation about image and aesthetics and race within the gay community,” Khary Septh, one of the creators of The Tenth magazine, a publication for queer people of color, said. Septh wrote the foreword to LÉWÀ. “I wanted to talk about how Luke could make this book but not one black boy on the planet could make this book and make it as successful as he was going to make it even though it might have the same artistic integrity perhaps.”

“I have to tell you,” Septh continued. “It has raised some eyebrows.”

On social media (mostly Instagram in comments of Austin’s posts but also spilling into Twitter) a few have questioned the photographer’s motives, the project’s central ideas, and Austin’s allyship. And while conversations on social media have gotten heated, it’s an important project to unpack.

While Austin’s intentions may be pure, this book exists within context. “At a very basic level you have a white photographer taking sexualized imagery of black men,” writer and art critic Antwaun Sargent said of the project. “That totally falls in a complete history that begins photographically with Robert Mapplethorpe.” Mapplethorpe’s imagery, particularly his Black Book, has been criticized for fetishizing the black body, dissassembling it and exocitisizing it for the benefit of the white gaze. There is a throughline from that work to LÉWÀ.

Of the 100 odd photos, about a fourth are of muscled bodies. In a sentiment almost identical to the most criticized Mapplethorpe imagery, some of those photos feature the models, faces obscured, their musculature and bodies exposed. They are sexualized images and at Austin’s own admission, are for his white audience. But the project as a whole also prizes a narrow understanding of blackness and beauty.

“The politics of the time is very different,” Septh said when Mapplethorpe comparisons were brought up, ”Luke is a democratically appointed Instagram photographer, Mapplethorpe was a patron-ed photographer a part of a downtown art institution. Culturally, Luke is not an art kid, he’s a social media star and that makes all the difference. Mapplethorpe is playing with eroticism in a stark way and I think we all understand that. Luke is taking the equivalent of cute boys in a bathtub.”

While it may be true that the source of Austin’s impact is derived from a different group, it doesn’t change the danger it poses. Times have changed indeed: social media can now crown its own standard bearers. But there is no less power in the standards they set, and arguably more with how Luke’s work can be instantly integrated into the life of anyone that has a cellphone. With this book, what is presented is still the case of a white man crafting the representations of black men.

That power that Austin holds is played out in his Instagram messages, of which he said he has had over 1,000 in the past week but stretch back to the first image of a black man he shot back in 2012. “I get messages from black men all the time saying ‘I see myself on this Instagram page and that made me feel good,’” Austin said. “I think that’s part of the reason I’m glad that this book came about is because when I get this many messages, then it’s clear that they don’t feel seen.”

And there’s weight to those feelings. These black men are finding joy in seeing representations of themselves in a space that they have seen to exalt only white bodies. There is meaning there. But this project divorces the photos from that context and doesn’t do the work to combat or challenge views.

“This doesn’t complicate anything,” Sargent said. “This is a coffee table book of black men that he shot, that doesn’t challenge the gaze at all. Perhaps hindsight is 20/20 and backlash has clarified a few things for him but [critiquing the gaze] is not what’s happening in these images.”

As Sargent later noted, there are a legion of black artists who are and have been working in this space. He name-checked Glenn Ligon and Isaac Julien from the 1990s as well as John Edmonds, Shikeith Cathey and Awol Erizku as present day examples. Those artists are deconstructing not only the gaze but the perceptions around it, recontextualizing cultural signifiers and their proximities to blackness. Austin’s work strips his models down to simply black bodies which is a trope that falls in line with the work of the most problematic white artists.

In his work Edmonds similarly shoots his subjects, sometimes faces obscured, wearing durags or hoodies. These items are symbols and in American pop culture, when put in proximity to black bodies, have a negative connotation. With his work Edmonds questions this process of assumption. Why can a durag not be regal? What is it about a black body in a hoodie that’s intimidating?

Parsons student and photographer, Myles Loftin also has done work, investigating the latter point. His project HOODED subverts existing imagery that exists showcasing black boys in hoodies by presenting them as joyous and carefree. “I wanted to know why I couldn’t find many images of positive portrayals of black teens,” Loftin told Vice. The work is personal because he was a black teen himself.

Cathey also speaks to this, distancing his work with the nude black male body from Mapplethorpe’s saying that his versions reclaim those bodies. That reclaiming can only happen through the lens of someone who has lived that experience. But the benefit of this book lies in the discussion that it has sparked. As more and more people attempt to be allies, it’s important to investigate what is true allyship, and what is simply a continuation, although possibly a well intentioned, but ultimately dangerous pivot of the same ideas that have existed for generations.