This past weekend, photographer Chris Saunders opened Pantsula 4 LYF — an exhibition exploring a distinctive dance style that’s emerged in South Africa — at UCLA’s Fowler Museum in Los Angeles. Pantsula crews use the Johannesburg townships’ bustling streets as the stage for their energetic, technical footwork, which has roots in American forms like swing, tap, and breakdancing, but also a combination of South Africa’s traditional dances including Zulu and many others. The movement is typically soundtracked by electronic music that recalls house and dance rhythms. Vibrantly colored workwear and sneakers are the crew’s uniform of choice — specifically, Dickies and Converse, accessible, durable, and adaptable garments to move in.

While some pantsula crews have traveled to showcase their steps on international stages, Saunders’s Fowler Museum exhibition is the first show on the subject to be mounted in America. There isn’t a comprehensive record of pantsula’s evolution over the decades — no official archive of the dance crews, their codes of dress, or of pantsula’s significance within South African culture. Since 2011, Saunders has been trying to change this. After profiling a pantsula crew for Colors magazine’s dance issue, Saunders met Dr. Daniela Goeller in 2012. Goeller, an independent researcher, had received a fellowship to study isipantsula culture at the University of Johannesburg. She’s since co-founded Impilo Mapantsula — an organization that unites crews across Johannesburg to support professional dancers — with four pantsula dancers and directors. For the past five years, Goeller and Saunders have worked to thoroughly document and analyze this unique culture’s history and impact, and are presently in the process of publishing the first book of its kind, Pantsula: Dance for Life.

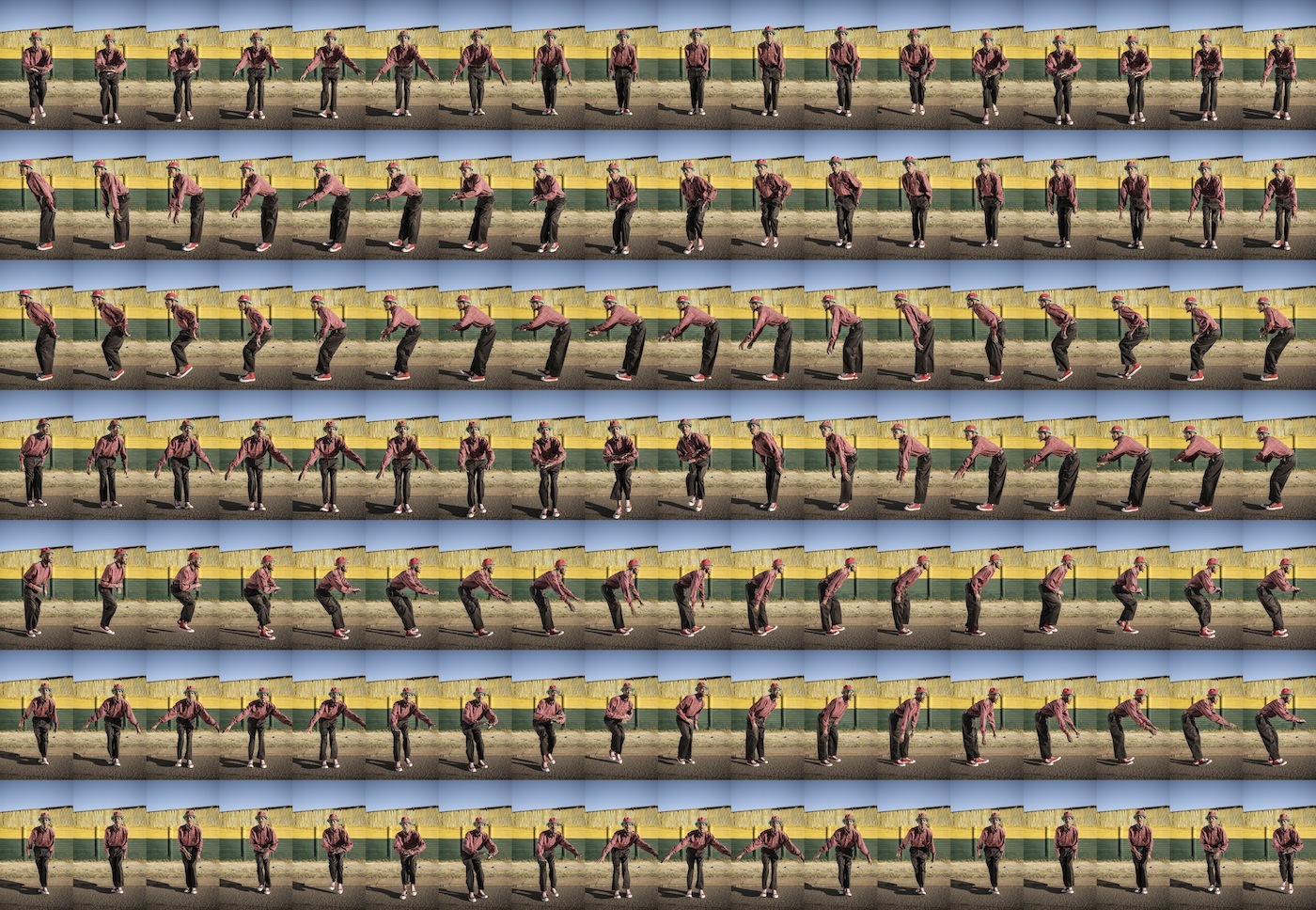

The book and the Fowler Museum show feature Saunders’s photographic contact sheets; adapted from videos, these image grids break down pantsula steps frame-by-frame, demonstrating just how nuanced the movement is and how skilled the dancers themselves have become. The projects also incorporate Saunders’s euphoric portraits — which blend elements of documentary and fashion photography to capture the crew members’ unique style on the street. We spoke with Saunders to find out how pantsula relates to social politics and how American workwear became its uniform.

When and how did pantsula emerge?

Pantsula is a dance form and a culture from South Africa. I use the word “culture” because it’s often perceived as a subculture, a small group of people. But growing up in Johannesburg, you realize this culture is actually incredibly big; it’s a big piece of the modern cultural structure of Johannesburg. It’s a modern dance, modern fashion culture, that mainly revolves around the dance side, the performance. But the fashion comes from 50 years of this culture developing into what it is today, and that’s sort of where the project goes. It follows the history of the culture itself and its development — it’s a documentation of many of the different dance crews throughout Johannesburg. It’s kind of like fashion portraits, but also portraits recognizing the performance within the culture. It’s documenting a culture which has never had a proper, full documentation of its existence. How often does that happen today?

How has the dance and its culture evolved over time?

I’d say in the 50s, it was almost a gangster culture. It revolved around the music — tap, swing, and American black music — that was coming into South Africa, and the dances that emerged from [these musical forms]. But as time went by and Apartheid took effect, people were being forcefully removed and relocated into townships. A lot of people from different backgrounds were forced to live together, and that impacted cultural development, and dance. Pantsula is sort of a combination of all these different cultures into one singular dance form. It has connections to mining and working culture, a culmination of multiple traditional dance forms, references to American swing, and real-life situations. The rhythm of the dance comes from the rhythm of the passing trains, for example. It’s really a modern culture — a modern dance and fashion culture that’s been influenced by the history of Johannesburg, the history of Apartheid, the history of freedom, like what’s happened within the last 10 years. It’s a mechanism of storytelling. It’s a long history, and that’s why I worked with an art historian on the book.

Can you tell me a bit more about pantsula’s connection to cultural politics?

The development of electronic music is a strong part of South Africa’s freedom. Kwaito is its own genre of music and difficult to explain without reference, but it’s almost like a lyrical form of house music, though much slower. The emergence of deep house in South Africa, and all the DJs associated with it, also influenced pantsula and the way the guys dance. So it’s a very flexible art form, and it’s constantly evolving with the times. That’s what’s great about it: it’s quite reflective of society at different stages. Yeah there’s a style in the dance and a style in the fashion, but you see it progress. Much like hip-hop.

Let’s talk about the clothing. Do different troupes have distinctive colors, styles, or even garments associated with them? And how did Dickies and Converse become the pantsula look?

American workwear is really interesting and accessible. Many guys work in mines or do other labor-related jobs, and that’s sort of how it emerged, but it’s since become more of a fashion statement. You can create a dance crew by buying fashionable workwear from a local shop, like City Outfitters in Johannesburg. It’s an easy way to develop a colorful uniform for your crew. Some also cut one side of the Dickies pant and join them to another pant to make the uniform cooler — it’s reengineering the pant. Crews wear two different color shoes, often Converse, a pair of Dickies, a smart shirt, and a bowtie. Another big thing is sporty, I think they’re called fisherman’s hats in the States?

Bucket hats.

Yes, bucket hats. It’s been a huge fashion trend since the 80s, through the 90s, and has resurfaced again in the city. And how you style your bucket hat is really important — how you fold the hat up, which direction you face it in. Each crew has a different attitude and different style to communicate it. How you lace your Converse [is important], too. In the UCLA show, there’s a section on the diamond lace style.

How did you first come to capture this culture?

I’m a white photographer, so I didn’t grow up in the townships, or experience that aspect of Apartheid in South Africa. But I started documenting a lot of street cultures in the mid 2000s, and did a residency in 2010 in Italy. I worked on a magazine called Colors, a cultural documentary magazine started by Oliviero Toscani, Tibor Kalman, and Karrie Jacobs in the 90s. The issue they wanted to do was called “Dance.” It’s funny I had to go to Italy to come back to South Africa! I documented one pantsula crew called Royal Action, and spent 10 days following them around.

What have been some of the more surprising, rewarding, and challenging aspects of this project over the past five years?

It’s been really difficult, because the culture itself is quite fragmented. There’s a lot of competition between crews, specifically when it comes to the commercial side of the pantsula dance. Crews are competing for work, competing for contracts when it comes to entertaining people at events. The guys are paid performers. So some guys didn’t want to give other guys their secrets, and it was challenging to get them to communicate with each other to tell their own stories. Like, how did this begin? Where did your crews come from? But we started gaining trust over time. It’s a modern way of documenting South African culture through partnerships and establishing long-term relationships with people.

‘Pantsulas 4 Lyf’ is on view at the Fowler Museum at UCLA through May 7, 2017. ‘Pantsula: Dance for Life’ is available for pre-order here.

Credits

Text Emily Manning

Photography Chris Saunders