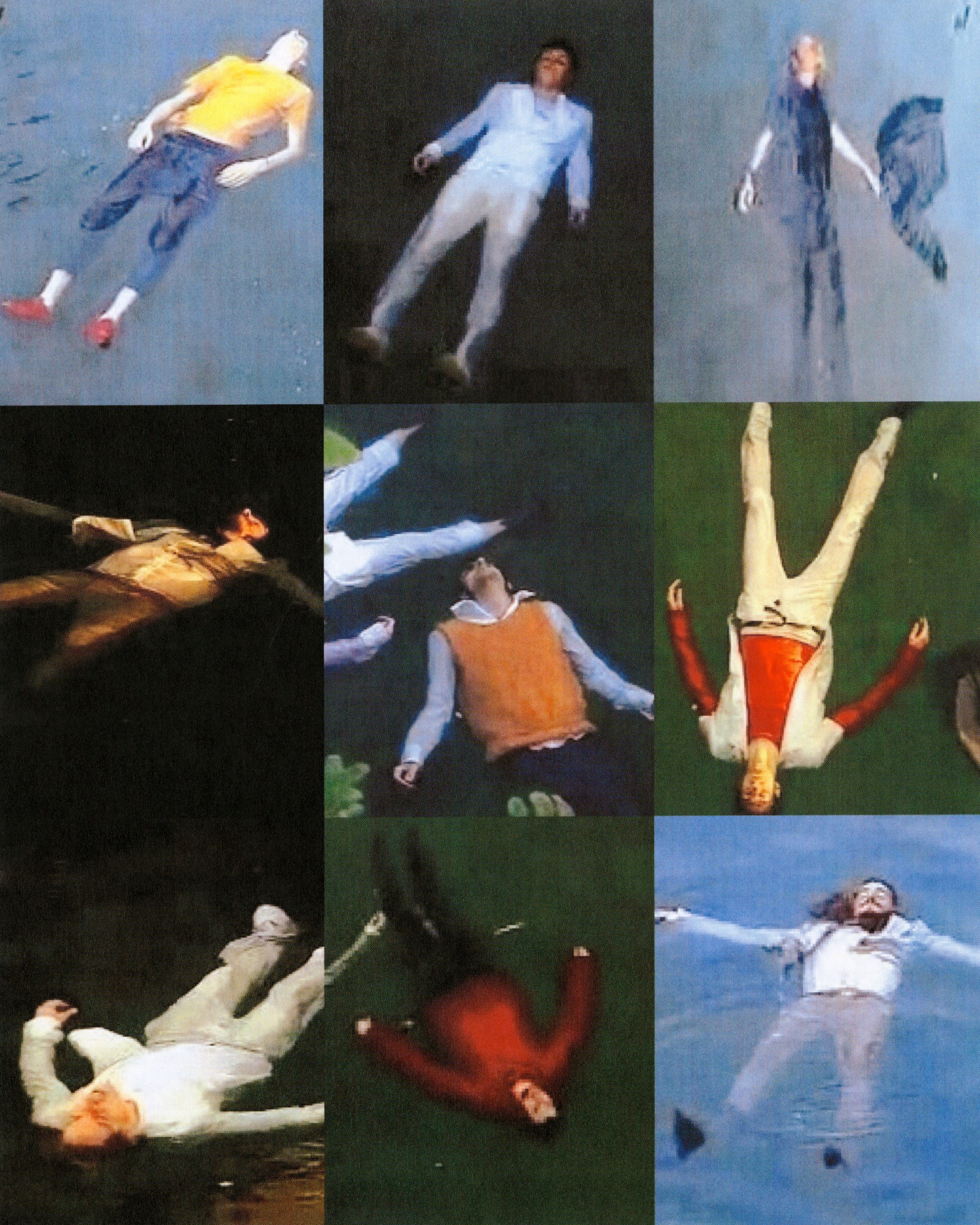

“We’re all standing around at this place that we’ve been told to meet for the show…” It’s June 2003 and photographer Frances Melhop has been invited to the bank of the Naviglio Grande, a canal that cuts through the south-west of Milan, for Carol Christian Poell’s SS04 menswear presentation. “We were looking around at the different alleyways or roads that the models might come down,” Melhop remembers, “and all of a sudden we just see this body floating down the canal, far in the distance, completely immobile.” Karlo Steel, founder of New York’s Atelier store, remembers his heart sinking. “We could see something floating down and I thought, ‘Oh no, this is dreadful.’ It looked like someone’s corpse.” Then the penny dropped – this was Carol Christian Poell’s SS04 show.

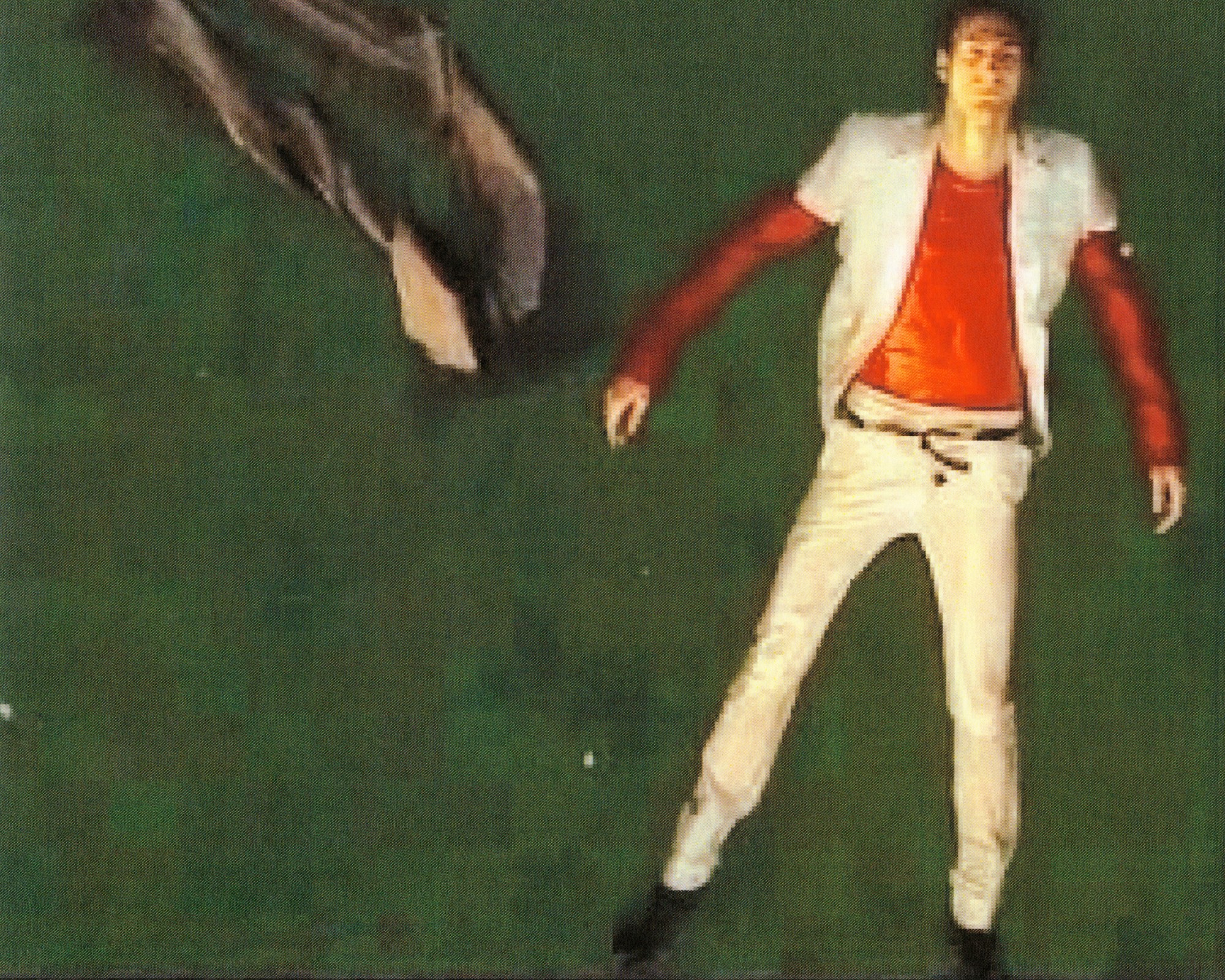

As yet more male bodies floated past, arms outstretched in a crucifix position, something became clear: this was not the Margiela-esque affair that the small crowd had been expecting. The collection, dominated by rich, lush leathers soaked in red dye and pristine white tailoring, was literally being shown in a dirty, polluted body of water. The stench was rancid. “It felt medieval,” Melhop recalls, “and we didn’t know whether they were alive or dead. But we were transfixed. We had to keep watching.”

Titled Mainstream Downstream, this fashion show is probably Carol Christian Poell’s best known work, and really, it’s one of only a handful of presentations that the designer put on at the turn of the millennium. Born in Linz, Austria in 1966 to a family of leather tanners, Poell trained as a master tailor there before moving to Milan to study fashion design at Domus Academy; there, he met his business partner, Sergio Simone. Together launching his first collection in 1994, the brand – which is still available today, in select stores like The Library in South Kensington or Darklands in Berlin – soon became known for launching its collections in distinctly strange and uncomfortable settings. For SS01’s Best Before, the brand presented models on stretchers wearing trousers whose waist was extended so far up the body that they took on the look of body bags. The chemical smell of the morgue permeated the room. For AW01, models were locked up in a dog kennel, the show space filled with the sound of barking and the stench of animals. “He was toying with all of our sensations,” Melhop recalls, “hitting every single one of them with every show that he did.”

For SS04, it was no different. Supported by inflatable floats, the stretched-out bodies of the models took the eerie form of Leonardo Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man. That was no coincidence. The Renaissance polymath had been responsible for key developments in this specific canal. Besides, as anyone with knowledge of Carol Christian Poell’s work will tell you, he’s a stickler for making work about the human body. “For other designers fashion is something on the body, it’s exterior to the body,” Ulrich Lehmann, fashion theorist and friend of Poell explains. “But with Carol, it’s not removed from the body – it’s part of it, and that is the fundamental difference between what CCP is trying to do and what other designers are trying to do.”

By this point, Poell had registered his company as CCP srl in an attempt to hide behind a company name, decentring the designer within the garments. The show is regarded by his followers as a landmark in the development of his design lexicon, as well as his overarching attitude towards the industry. The very name of the collection, Mainstream Downstream, reads as an indictment of the industry at large: he is ‘downstream’ – as in, ahead – looking back at the ‘mainstream’. Although not the only designer to create work about the fashion industry, as Lehmann points out, his approach is different to other avant-garde designers – at the end of the day, “Helmut Lang, Margiela: they sold their companies for a lot of money and then they became artists.” Lehmann describes Poell’s practice as similar to someone like Massimo Osti. “There is an approach to studio and research work that is closer to what artists and scientists do; they create an environment where time is not so much of the essence as [it is] in the fashion world.”

Poell’s garment construction is embodied, literally; perhaps even making you uncomfortably aware of your own. The designer takes his cues from human anatomy. Skin is frequently evoked: veins are often visible through heavily-treated opaque leather (achieved by injecting paint into the animal skin with flesh still attached); garments possess edges that don’t quite meet, conjoined by threads that take on the look of scarring or medical stitching. Accessories, meanwhile, might be made entirely from human hair – as legend has it, he may have even intended at one point to use human skin for a piece. A handbag made from a taxidermied piglet, which was formed from the whole animal with just a handle attached, was shot by Melhop for an exhibition curated by Walter van Beirendonck in 2001. “It’s Carol Christian Poell making this comment about how ridiculous fashion is, getting to the point where you would carry a bag that didn’t work, didn’t function,” the photographer explains.

”He was toying with all of our sensations, hitting every single one of them with every show that he did.“

Frances Melhop

“I want to make my trends personal. This collection and this presentation are my take on the state of fashion now,” the designer said after his SS04 show. Evidently, he didn’t find what he saw very healthy. “It’s someone who was absolutely making a stand against mainstream fashion, against the corporate erosion of creativity that has since permeated the industry,” Eugene Rabkin, fashion journalist and long-time follower of Poell’s work, explains. It was around the time of this show that Rabkin first took a pointed interest in the designer through the Fashion Spot, the Blogspot-era bible, before later founding his own site, StyleZeitgeist, where experimental, avant-garde menswear was the focus. Carol Christian Poell’s work became a main object of fascination. At the time of writing, the ‘definitive’ thread on the designer has a total of 707 pages. Rabkin is still active there, helping newcomers with their queries on how to source replacement zippers or where to get their pieces tailored. Poell’s work still has a strong grip on menswear aficionados: new Carol Christian Poell leather jackets retail for upwards of £5000 and to purchase one second-hand will set you back just under £3000.

For Rabkin, Mainstream Downtown marks “the end of a golden age of fashion.” He cites the early 00s as the moment where a boom in the commercial success of more experimental, conceptually-driven designers – names like Martin Margiela, Helmut Lang, Alexander McQueen and Viktor & Rolf – was coming to an end. By the early 2000s, large conglomerates began purchasing independents, bringing with their capital a requirement to meet commercial quotas. The political moment in the West – after 9/11, and as the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan were in their early days – was also reflected in the show, if only through the abject terror of those who witnessed it. “There was also a sense of instability and a loss of faith in mainstream political institutions,” Rabkin reflects of the morbid contemporary mood. “And Carol [is thinking about how] the body is subject to decay and death.”

”The smell, heat and the models not necessarily throwing up but feeling a bit unwell… it suggests [fashion] isn’t a dramatic narrative, but a laborious production.”

Ulrich Lehmann

“As soon as he shows the collection, he puts them in the water and he destroys them,” reflects fashion historian Caroline Evans. “It’s like a bonfire of the vanities.” Evans has written extensively on avant-garde fashion’s preoccupation with ecological and geopolitical anxieties around the turn of the millennium. “What really strikes me about Carol is, why would you show at all if you’re taking yourself out of the fashion system?” she asks. The fashion show is traditionally a spectacle of commerce, used to sell the clothes and bags within it. For Lehmann, it’s this emphasis on the object, rather than the image, that is the purpose of a show like Mainstream Downstream. “You’re talking about a period when CCP as a team was still experimenting with the idea: can we do a catwalk show?” he explains. “How do you communicate how long it takes to construct [something]? Through the smell, the humid heat coming off the dirty canal and the models not necessarily throwing up but feeling a bit unwell… it isn’t a dramatic narrative, but [instead] suggests that this is all part of a laborious production.”

A day or so after the show, the garments that had been worn in the canal (and consequently soaked in the rancid water) were put on display at his showroom in Milan, a time and place typically put aside for buyers to come and see the collection before putting in an order. Heavy, warped leathers were still drying out and cotton had been wrinkled. The garments were effectively ruined. Yet they possessed a certain appeal. ”They didn’t have that strict linear thing that he was known for, and I was really drawn to that. I liked how the water had actually changed the structure of clothing,” Karlo Steel remembers. He tried to order a selection of the garments as they were presented – crumpled and damp. He was told no: the garments would not be pre-soaked before delivery. It was, in typical Carol Christian Poell fashion, another artful slight against the fashion system.

Text: Eilidh Duffy