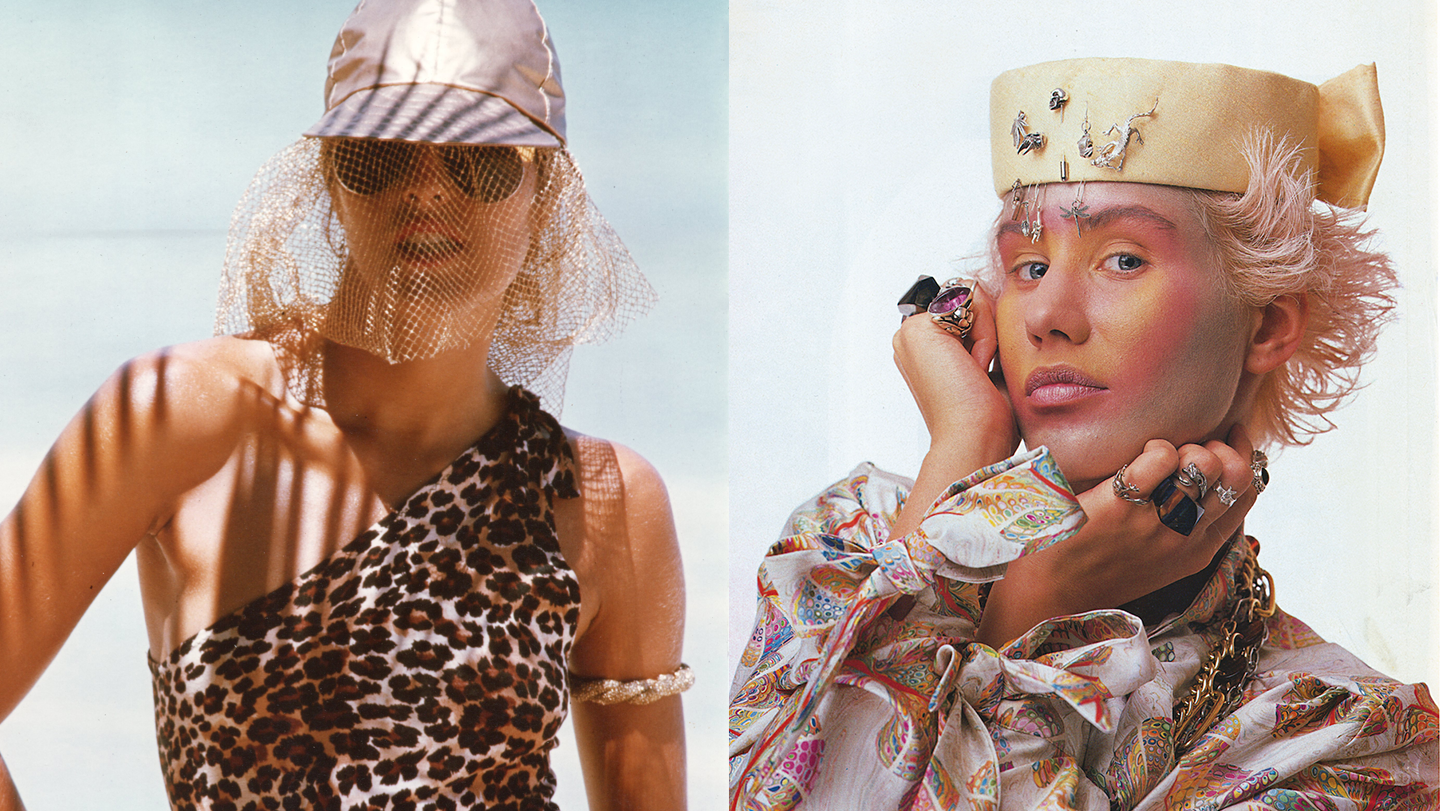

Starting off her career at the ground-breaking Nova magazine in the 60s, Caroline Baker went on to define the role of the fashion stylist over the next 30 years. Now, a new book, Rebel Stylist: Caroline Baker, The Woman Who Invented Street Fashion, charts her career across 272 lovingly-curated pages. Throughout her reign, she pushed against the catwalk-dominated trends, instead creating looks through the ensuing decades that empowered women by showing that personal style mattered more than exorbitant budgets, and that fashion’s rules were made to be broken. Her editorial work at not only Nova, but notably also the early issues of i-D, as well as Vogue, The Face and The Sunday Times, set a standard which ultimately earned her the accolade of being the godmother of all stylists.

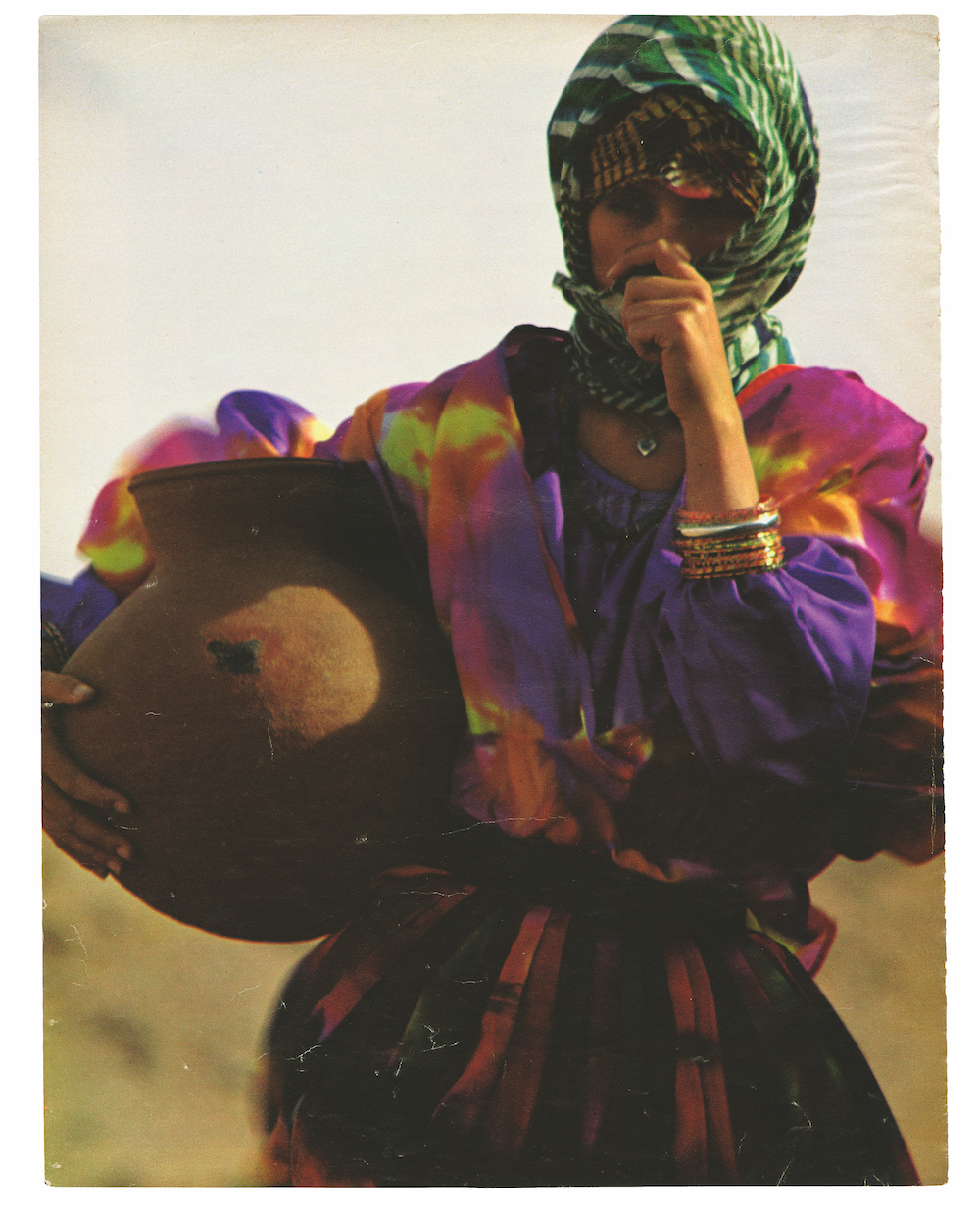

Designers including Vivienne Westwood and Katharine Hamnett loved to work with her, as did high street brands such as Benetton, all of whom appreciated her instinctive ability to infuse the mood on the streets and political activism into collections or advertising campaigns which were both diverse and properly modern.

The book includes never-previously-published work by legendary photographers such as Guy Bourdin, Helmut Newton and Sarah Moon, written contributions from Baker’s former collaborators, like Westwood and Hamnett, and, of course, commentary from the super-stylist herself. Authored by the writer-curator-academic Iain R. Webb, formerly a fashion editor at titles including Blitz, The Times, Elle and Vogue Russia, the book unpacks Baker’s trajectory and influence, underlining not only how original her approach to fashion was from the outset, but how much it resonates with today’s landscape.

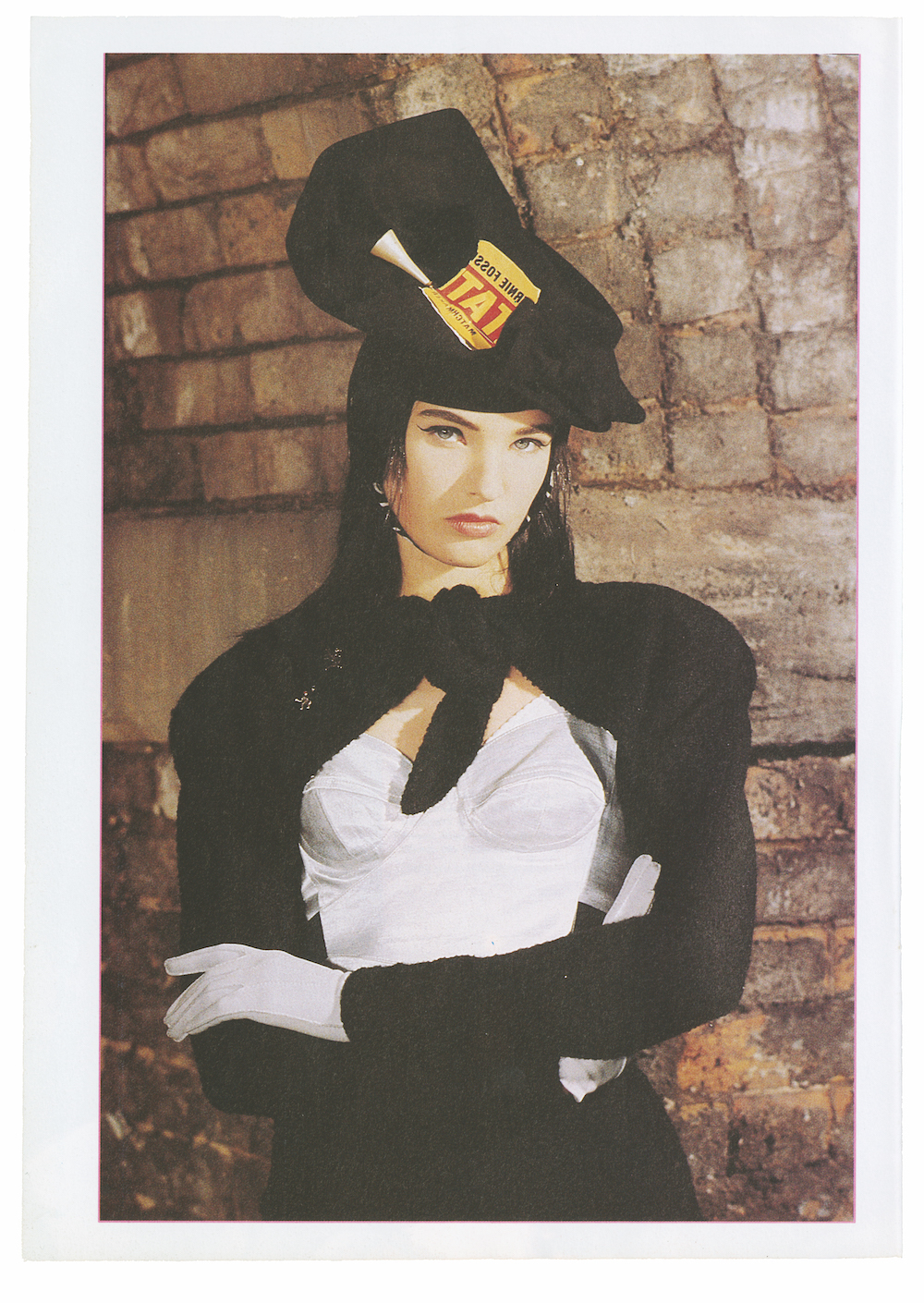

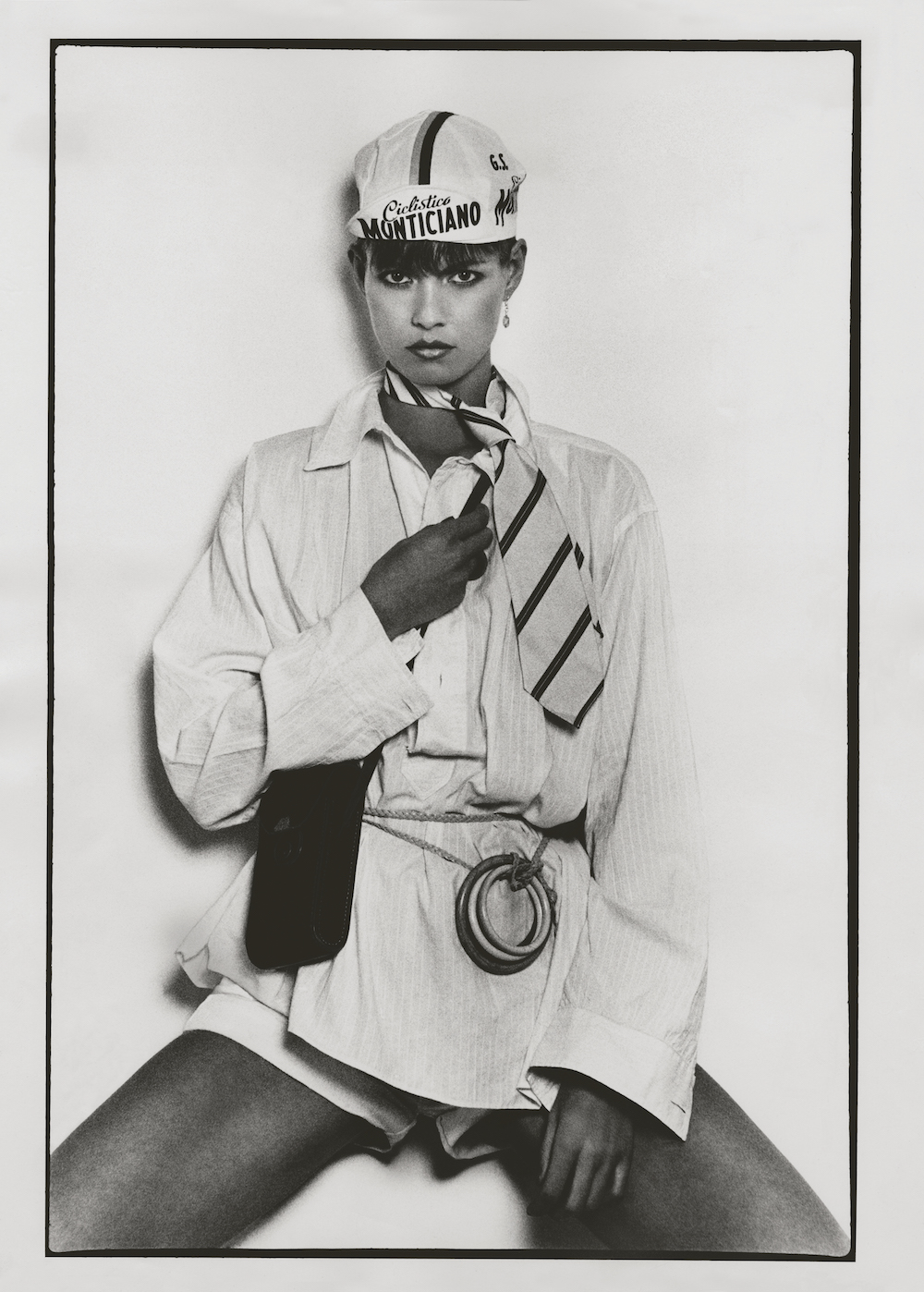

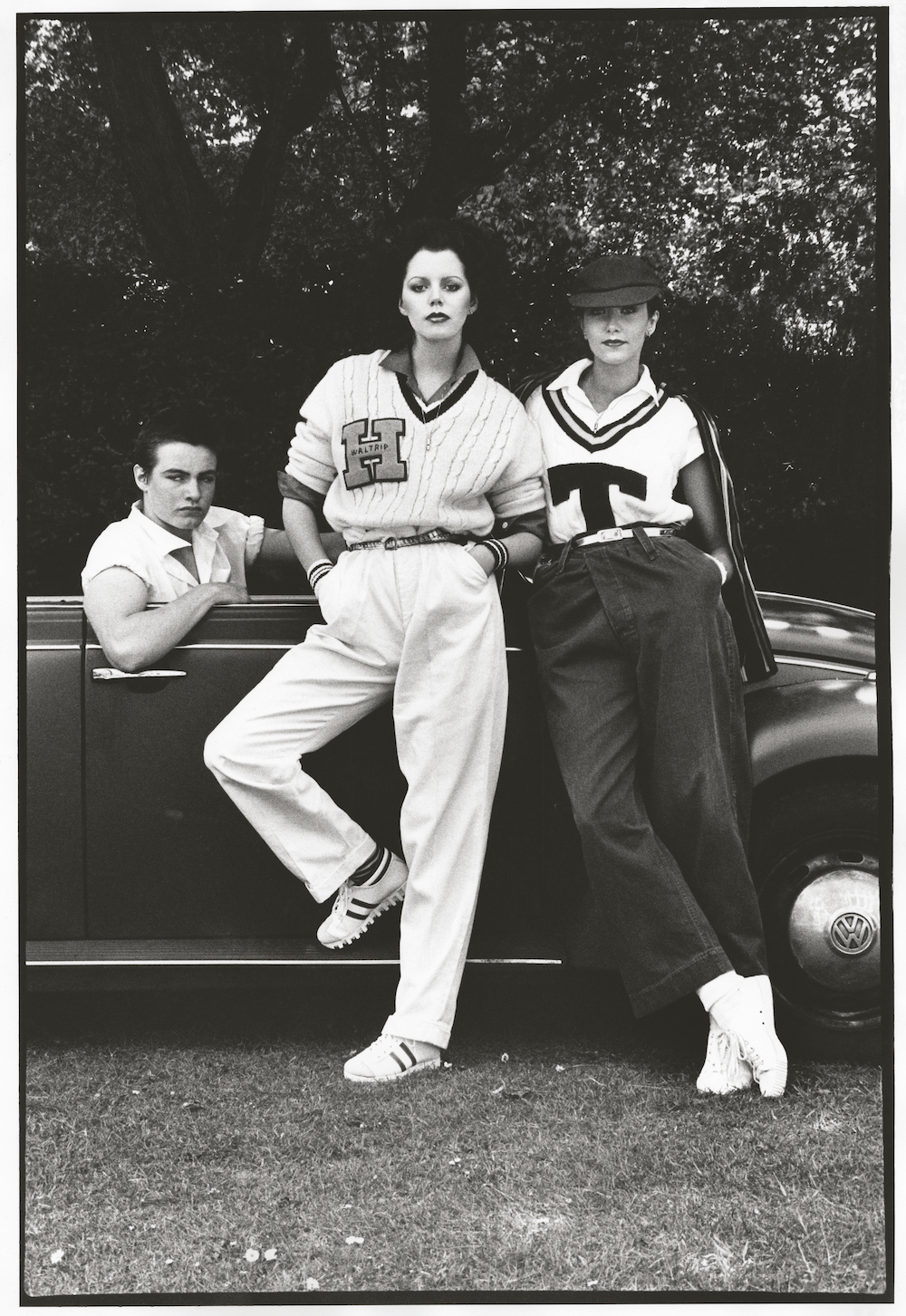

Baker was, after all, a sustainability pioneer who utilised second-hand clothing and discarded military uniforms within fashion editorial when no one else did. She broke down gender barriers, dressing women in clothes which were traditionally reserved for men. She was the first to adapt sportswear into a high fashion context, and she collaborated with specific designers, long before the significance of a stylist’s input was even recognised within the fashion industry. She also promoted diverse street casting, often using non-models in her work. All of these have since become fashion industry norms.

Here, we meet Iain R. Webb to find out more about the stylist who brought a whole lot of substance, fun and rebelliousness to fashion.

Was Caroline the first stylist in the sense of how we now recognise it: as a creative profession in its own right?

Although it might sound trite to today’s media savvy generation, Caroline offered a ground-breaking perspective: it was not what you wore that mattered but how you wore it. This approach precipitated a paradigm change in how fashion was communicated and, more importantly, how women dressed. She was a trailblazer in finding inspiration beyond the catwalk.

When did you first become aware of her work?

As a teenager in the mid-70s, I first encountered Caroline’s work in 19 magazine and RITZ newspaper and possibly an odd copy of Nova, which my older sister used to buy. Around the same time, I tore pictures of her out of The Sunday Times and one of those cuttings — a story about girls who dressed like boys — features on page 100 of the book. Her maverick approach to what fashion could be and her seemingly haphazard way of combining pieces of second-hand clothing with designer items echoed the punk aesthetic, which was immensely appealing to me.

In 1981, after studying Fashion Design at Saint Martins. I wrote to Caroline for a job. Her rejection letter also features in the book. During the 1980s we both contributed to the new troika of style magazines: i-D, The Face and Blitz. I remember each month scanning her pages and wishing that I could have thought of that particular, peculiar idea; that way of using clothes to dress the model. We shared the same irreverent viewpoint. In the 80s, we both represented a new version of fashion practitioner, the stylist, and we both featured in an article titled ‘The Stylistics’, which attempted to explain the importance of the stylist ‘in forming the images that flood our style-obsessed media’. Maybe one day we will get to collaborate and make fashion pictures together.

What was radical about Caroline’s approach to creating fashion and style stories when she was the fashion editor at Nova, compared to other fashion editors at the time?

Caroline didn’t follow fashion, she created looks fuelled by her mood and personal perspective. She was totally aware of what was happening around her in society and referenced politics, prejudice, sexual and social injustice in her work. She promoted the concept of a strong, powerful woman who was an equal to men. Her radical approach certainly provided a blueprint for future generations. The role of the fashion editor, for the most part and certainly at that time, was to present their readers with the looks dictated by the designers. Fashion pages were a shopping list. Caroline offered a new version of fashion, a DIY style that promoted an individual approach.

Instead of looking at the designer catwalks she was inspired by how people dressed around her on the street. This was a totally innovative viewpoint that turned fashion on its head and introduced the notion of personal style to the mass market, something that became the focus for fashion in the 80s.

Her work is recognised for its underlying political and feminist narratives – where do you feel this is most powerfully seen, within her archive?

Throughout her career Caroline championed equality for women, and at its most obvious this can be seen in her embracing of menswear. She dressed herself and her models in second-hand suits that she made fit with belts, ties and bits of string. She preferred men’s clothing because of the practicality of pockets. She rejected the ‘dress-up doll’ looks and, through her editorials, told women that they need not dress for men. From the get-go she also told her readers that they need not buy new clothes. This anti-fashion stance was totally inspirational.

Did Caroline have a similarly innovative approach to casting?

Caroline railed against the prescribed concept of the perfect painted doll-like beauty, preferring models who had character. She was extremely keen to present a more multicultural version of fashion that reflected society and particularly her surroundings. She endeavoured to include Black models in her fashion stories, although, at the time, this was not the norm. For several of her fashion stories she would feature non-models, choosing instead someone with the right look for it. This could be a designer’s assistant that she encountered, or a dancer. Her approach was more like casting a film than a fashion story.

What links her work, across the decades, to the work made by some of today’s major stylists? Where do we see ‘Baker-isms’ occurring now?

Caroline’s rule-breaking and make-it-up-as-you-go-along modus operandi is now part of the established teaching on fashion courses in universities around the world, which I am sure would amuse her. Humour and the way in which Caroline had fun with clothes, she didn’t treat fashion reverentially, has been central in her work and is one of the things that can be seen in the work of today’s super-stylists such as Ibrahim Kamara and Lotta Volkova. Caroline didn’t care that the clothes didn’t fit the model – she would merrily chop into and safety pin things back together; this ‘too big, too small’ silhouette is now firmly part of a modern aesthetic.

Which of Caroline’s collaborations with designers or brands do you feel were her strongest?

It is extremely telling how Caroline collaborated with Katharine Hamnett and Vivienne Westwood — two of fashion’s most politically driven fashion designers. All three women used fashion to make statements about issues they cared about, be it women’s rights, human rights, anti-war or climate change. They represented a new generation of creatives. Caroline’s collaboration on the Benetton campaigns with photographer Oliviero Toscani were ground-breaking too, especially the way in which they proposed advertising campaigns as a platform for messaging, which was decades before current conversations.

How important were Caroline’s contributions to the early issues and direction of i-D?

Caroline was one of the original contributors to i-D, having worked previously with the magazine’s founder Terry Jones in his previous role as Art Director of British Vogue. Caroline’s advocacy of fashion as a means of personal expression and individual style was like a template for i-D and the other style magazines that emerged at this time. In the debut issue of i-D Caroline rallied the readers to “Originate don’t imitate. Find your own i-D”.

‘Rebel Stylist: Caroline Baker, The Woman Who Invented Street Fashion’ is out now, published by ACC Art Books.

Credits

All images provided by ACC Art Books