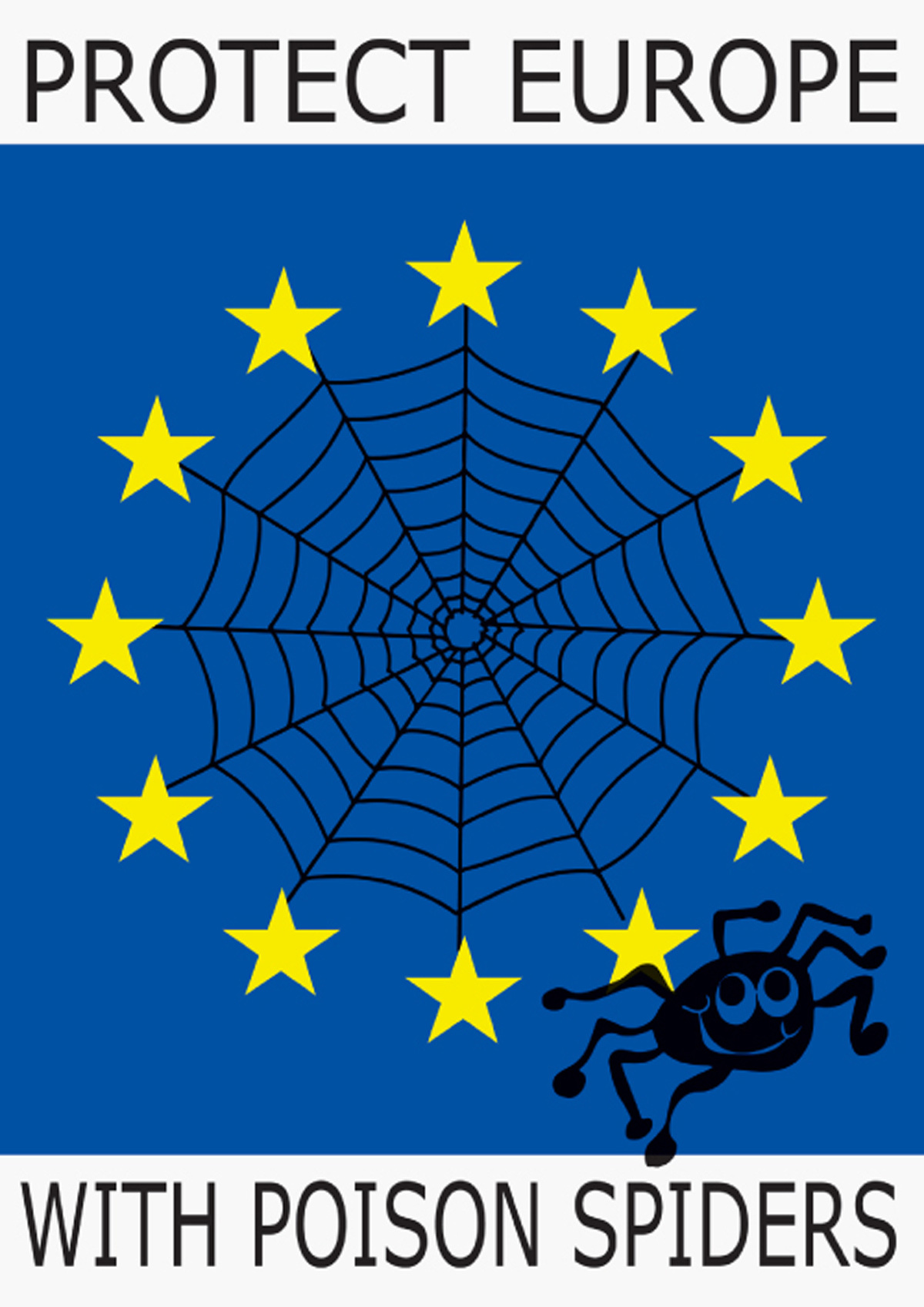

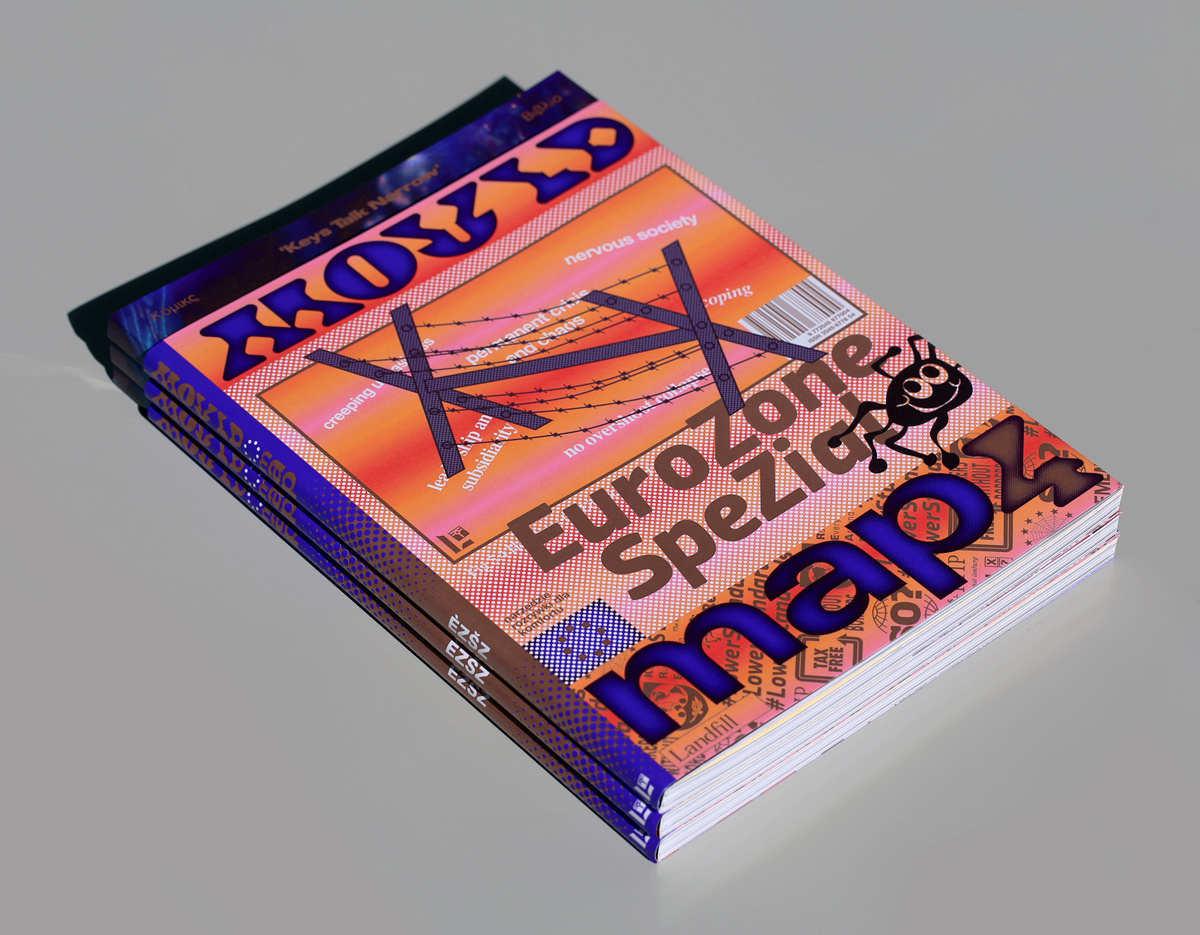

Although it was founded in 2010, issue 4 has only just come out and this time around it’s a collection of comics, artworks and investigations into historical counterculture commissioned around the theme of “Europe and its possible futures” – one that’s taken on a heightened political relevance in light of the refugee crisis, the Greek debt crisis, and the rise of Jeremy Corbyn. So amongst its many pages you’ll find a parody newspaper from conceptual artist Amalia Ulman about Carla Bruni, Nicolas Sarkozy and breakfast croissants; a bittersweet story from comic artist Roope Eronen about a punk cyborg from future Helsinki; posters exhorting us to “sterilise the one %” and “protect Europe with poison spiders”; an essay remembering 70s radical inflatable-art community Action Space; even a selection of colliery commemorative plates celebrating mineworkers’ unions.

Hugh Frost and Leon Sadler make Mould Map, and following is what they’ve learnt about cartoons and European politics along the way.

What is Mould Map exactly?

Hugh: The latest book is pretty explicitly about European social and political ideas, but that’s a first. It was what we wanted to focus on this time, using European artists to mix a type of reportage and narrative art in a more specific way. The first book was inspired by 60s UFO-slash-Roswell zine culture, the second was an attempt to make a book positioned out of time by blending ancient and futuristic aesthetics, book 3 was about network technologies and post-humanism. Even the latest Euro political collection is heavily sci-fi and design fiction [the use of narrative to explore possible futures for society and technology] based. I think they always will be somehow.

Leon: I think that when they started those sci-fi mags in the 70s, things like Métal Hurlant [French comics anthology] or 2000 AD, they were really finding new and proggy ideas and visuals that reflected the time they were made, and we are trying to make our idea of a weird science-fiction collection in the present day. It’s a book of comics and art for people who are interested in that old stuff as well as new things.

Why did you decide to start?

Hugh: As a way to bring together the work we were interested in from a really interesting scene in print and online (predominantly coming from the US), also to package and frame it in a clean way for another audience who maybe weren’t interested in traditional comics or had a misconception of what comics were or could be.

Leon: We want to make books where we carefully and slowly think about what happens by putting certain artists’ work next to each other, how the works balance or disrupt each other you know… I think initially we wanted to just make a really tight collection of sci-fi comics and art, it’s expanded since then, but that’s the core of each book.

A lot of the artists come from a DIY background so we are also quite fanboy about it, dreaming about how their work will look printed in a fancy way. And I think we are also quite contrary obnoxious people and are driven to make books in opposition to the ones we hate.

Issue 4 is something of a departure because of its explicitly political content. What exactly was its theme?

Hugh: The first rough outline was that the book would look at forms of cultural activism with a focus on speculative fiction – literary, graphic, and cinematic. Stories as tools for opening up new possibilities. Potential near-now worlds beyond manifesto-pledge rhetoric. More specifically, thinking about automation and citizens’ income. Basically wondering if our social systems are going to evolve at pace with production and financial technology, or if tech developments will only entrench existing inequality or even make it worse. And picking up on recent health-goth moods as an ambient background question about the place of the majority in a potential coming split of the species into regular meat-bags and tech-augmented ubermensch and so on. Also drawing links between classic sci-fi dystopias and current possible legislation such as TTIP [the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, a series of trade negotiations that has been described by War on Want as ‘an assault on European and US societies by transnational corporations’] – basically if we want to end up in some Elysium [the Neill Blomkamp film] or Mega-City One [from the Judge Dredd comics] situation the quickest way to get there would be by giving foreign financial interests the ability to sue governments for damaging profits by protecting citizens. Where is the bleed between sci-fi nightmare and the political economics of today?

But this proved to be too defined and limiting a brief and in the end the simple text artists were asked to respond to was: ‘KEYS TALK NARROW / Mould Map 4 / Eurozone Spezial. Uncertainty. Money. Technology. Ecology. Tragi-Comedy. A book about Europe and its possible futures.’

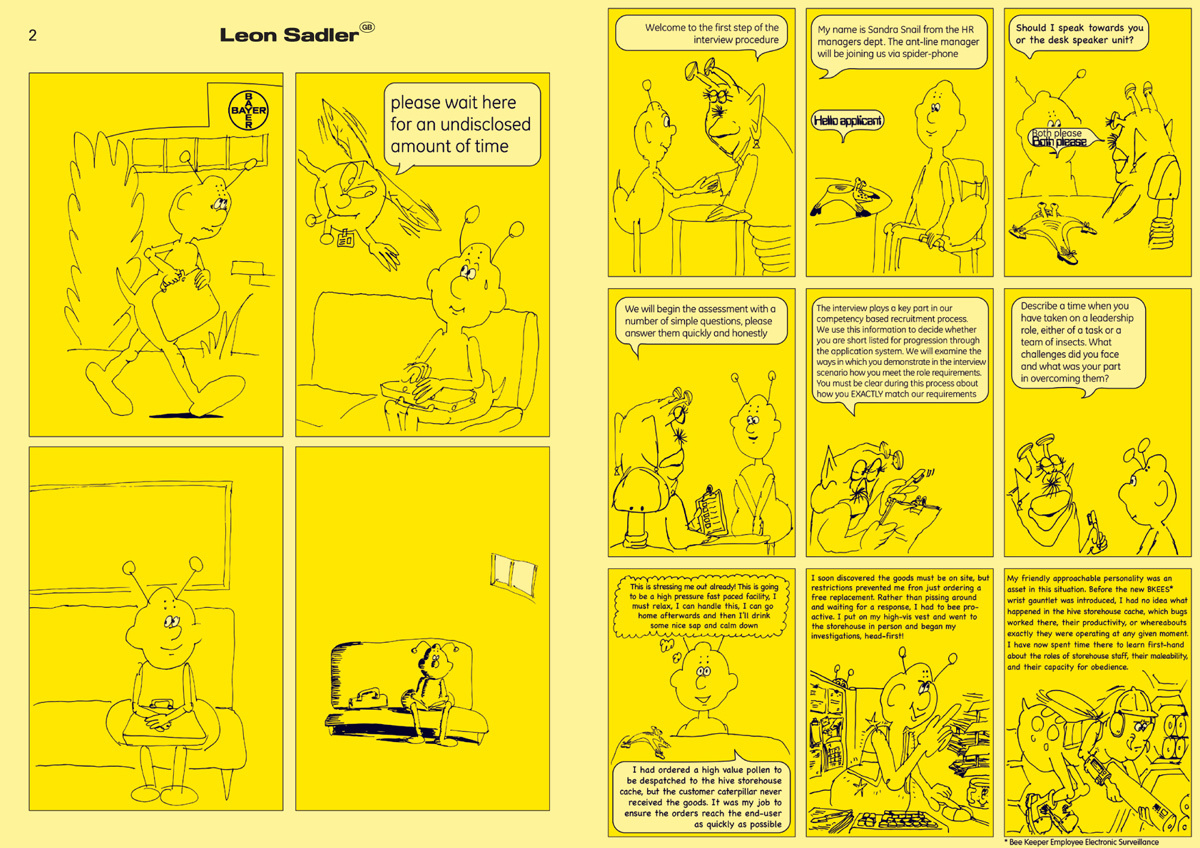

Leon: The packaging of the book is the most overtly political bit. Inside, the artists engage with things at all kinds of levels. Patrick Crotty has made a comic about his perpetual intern character and his daily struggles. The script for my comic is just a job application that I wrote, and then tweaked it to make it more horrible.

There’s always a fear of being preachy, but I can say we aren’t afraid to say simple obvious things. When you’ve got an important thing to say I think it’s better to have it visible straight away, and have some more subtle ideas inside it that can present themselves when you read it the second time. I think we are both very influenced by Neill Blomkamp and the way he makes such direct chunky statements, it’s such a free and expressive spirit.

Think of Mould Map as a bit of propaganda too, entertainment and brainwashing go hand-in-hand so we also have to consider that!

Most of my artist friends are against taking a clear political stance in their art, but this appears to be less of a worry in your book.

Leon: It’s okay, the people in Mould Map are cartoonists and anarchists (even if they don’t wear the badges) who also happen to make art too so it makes sense for them to do this stuff. Traditionally, cartooning has always been the art form closest to political discourse, the form is such a natural fit. If you look at it from that angle, Mould Map is quite a traditional book, it’s just that it also has some non-comics crammed in there too as a way of building an atmosphere and a wider conversation.

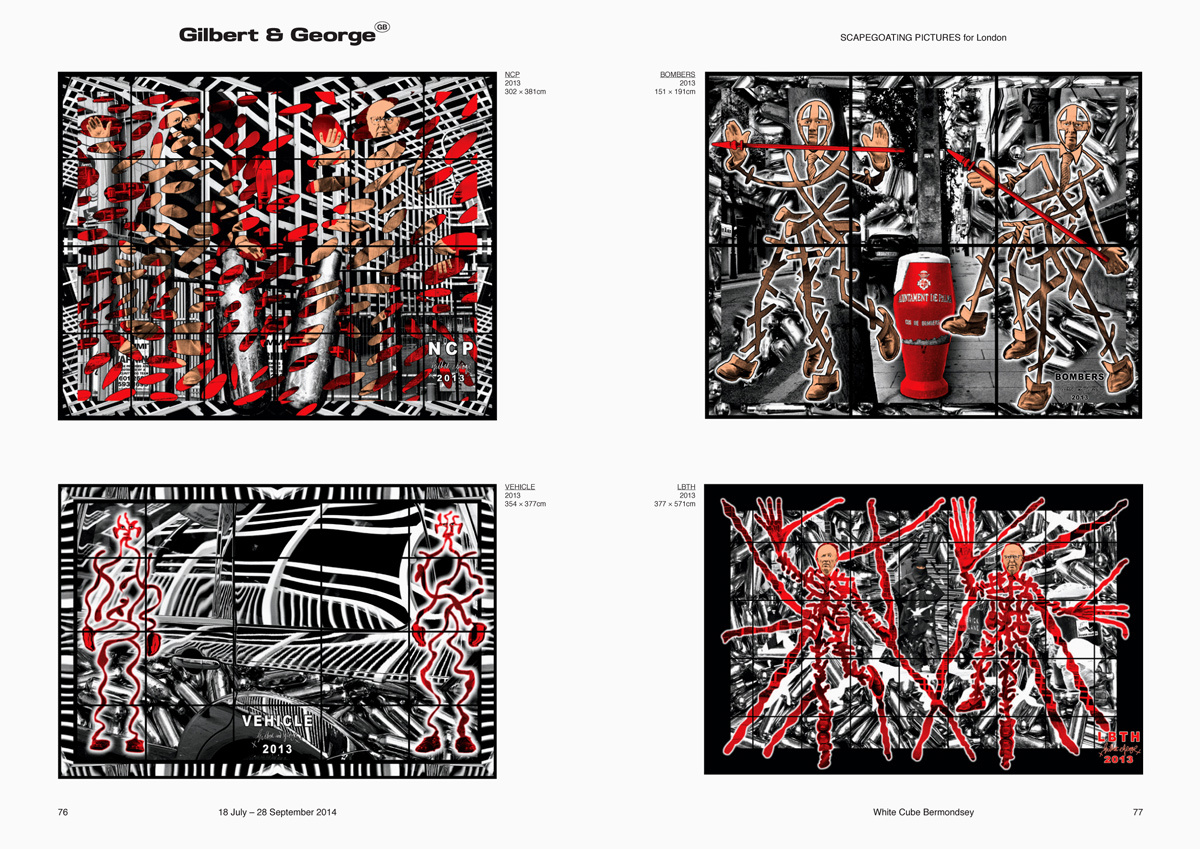

Hugh: I think the most important thing is to ‘stay with the problem’ – to be specific. So these stories reflect the real world of covert trade deals and corporate lobbying, anti-street-sleeping spikes, stress-induced colouring-in book sales, Trident renewal, management language, Golden Dawn, surveillance and so on. So to varying extents the work acts as visual journalism. Sometimes as straight reportage diary comics like Grace Wilson, but also in the trippy, balloon tweaked streetscapes of Gilbert & George.

About art – Herbert Read described art history as a series of changing symbols for reality. All this stuff is our reality and this is how we are processing it.

How important is humour to this process?

Leon: Humour diffuses the annoying preachy tone, it humanises your message, it’s satisfying, it’s perfect! If you think of British comedy like Little Britain, The League of Gentleman, The Day Today, Da Ali G Show, it’s incredibly entertaining but the political subtext is also right there at the surface, and that kind of propaganda is undeniable, it’s powerful stuff. I only recently realised that my political outlook is shaped by the British comedy I watched growing up. For me I always seek out art that is funny but also has that cheeky, angry kind of feeling about the world that I share.

Having now finished the issue, what changes would you most like to see in Europe to ensure a brighter future?

Hugh: A reassessment of European priorities, putting health, housing, education, sustainability, humanitarian responsibility, equality and culture over abstractions of growth.

Leon: Hmm, god I don’t know, how do you make people more kindhearted? It seems like the most important thing!

Credits

Text Dean Kissick

Images courtesy