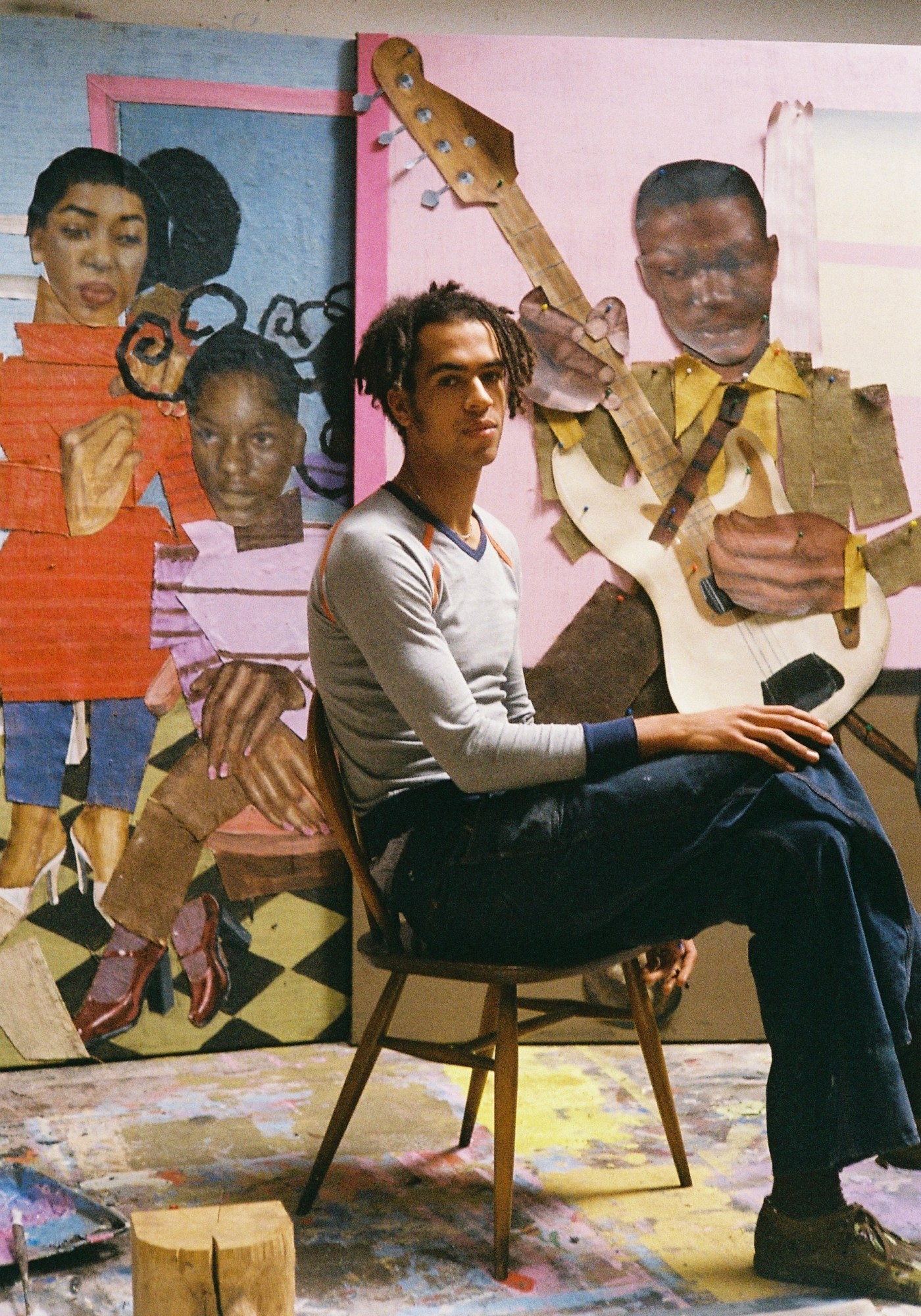

portrait by GLORIA PESCARU

Cato appears on my laptop screen mid-tea sip. We’re talking over Zoom, but he’s fully here: animated, thoughtful, and already halfway into a story about dragons he drew as a kid that his mum promptly framed. “That’s probably the moment when I realized I could draw,” he says, “and that I was good at it.”

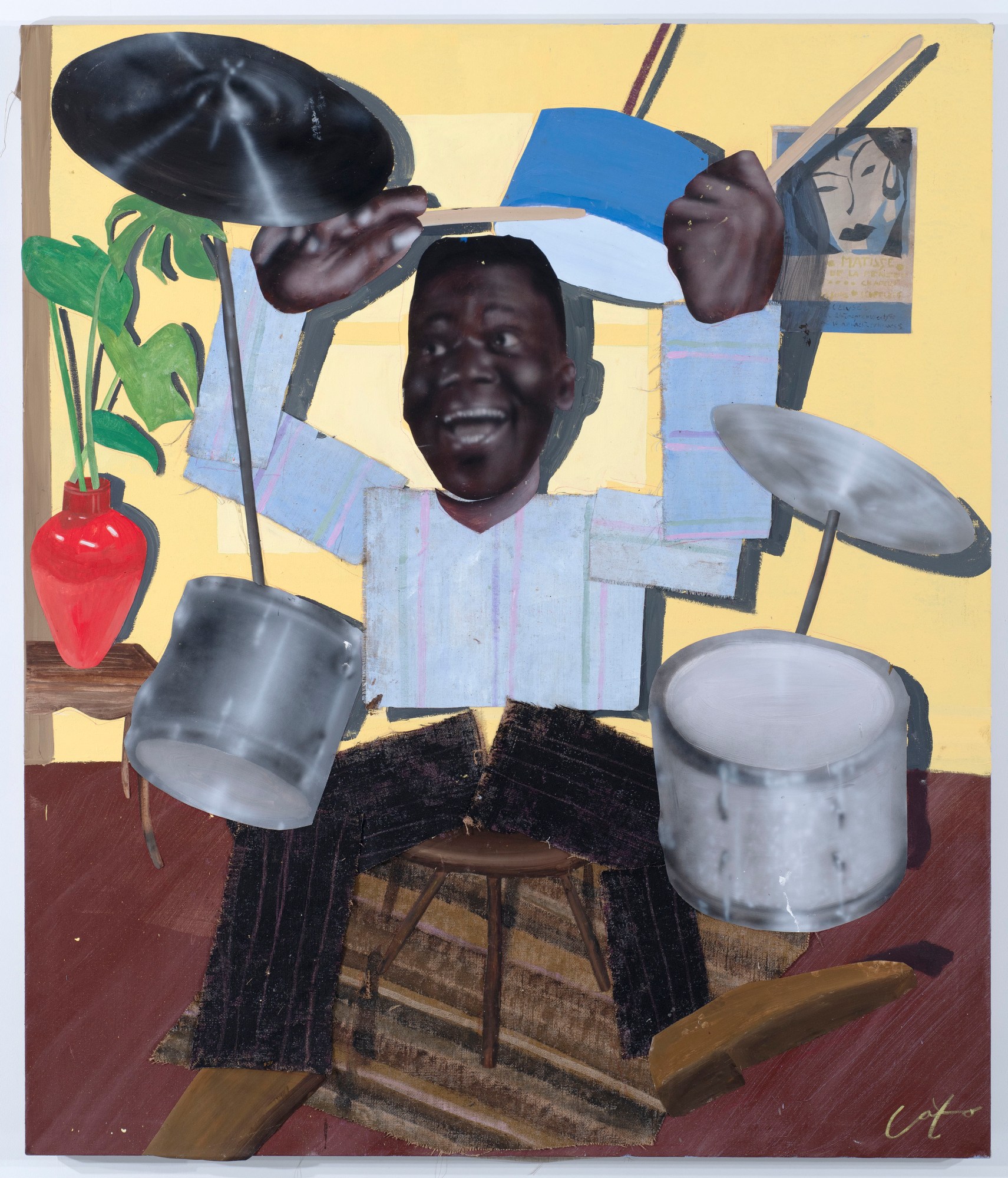

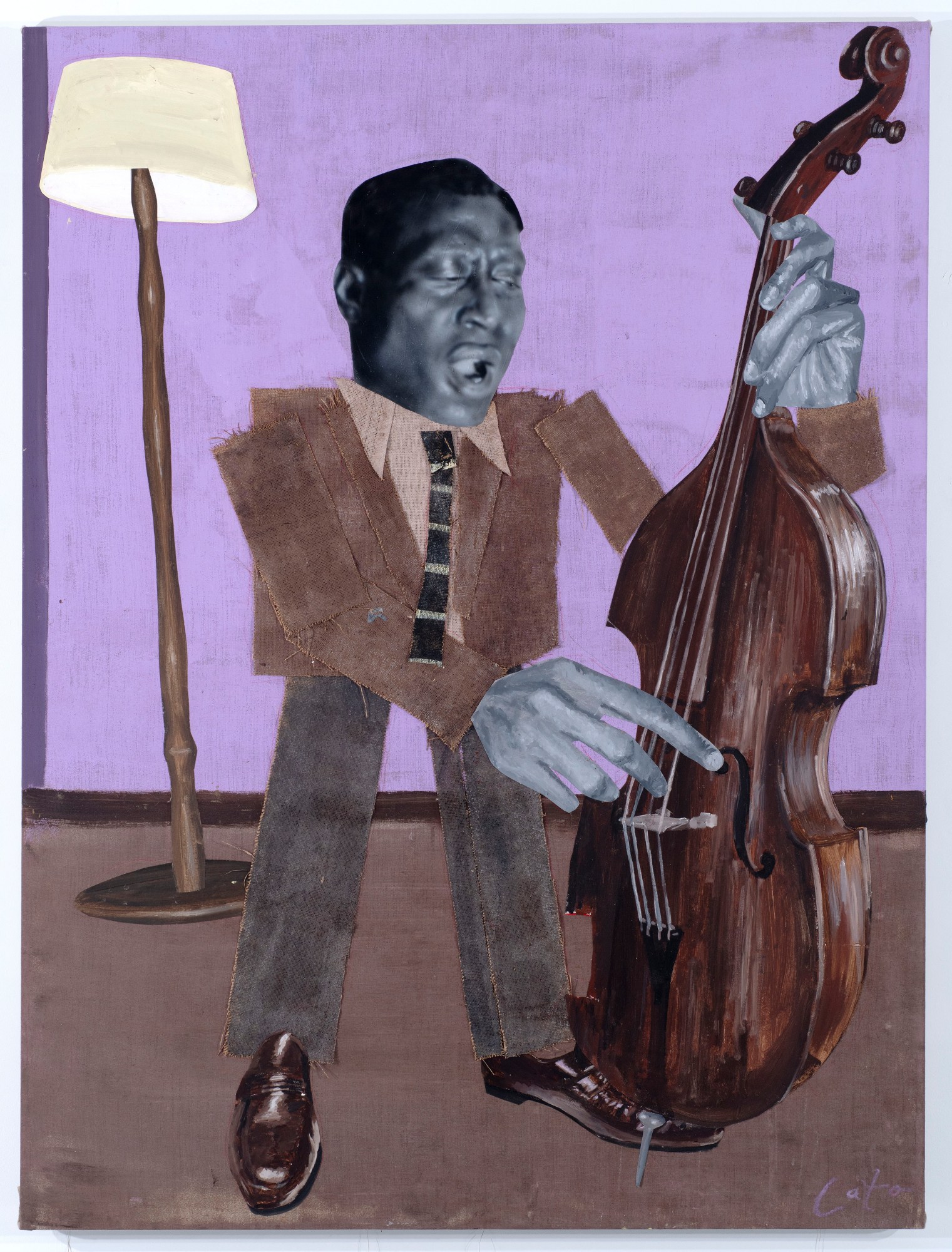

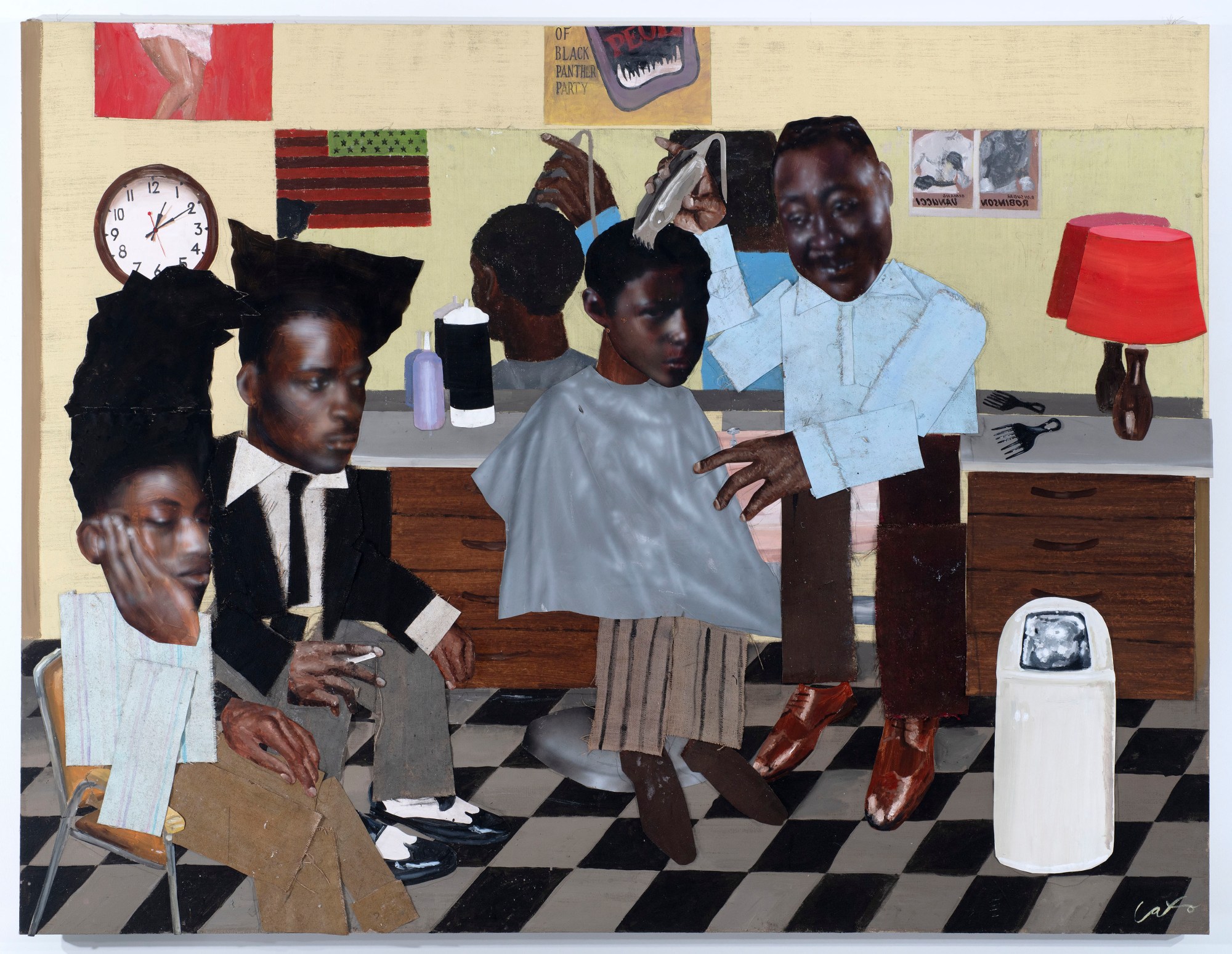

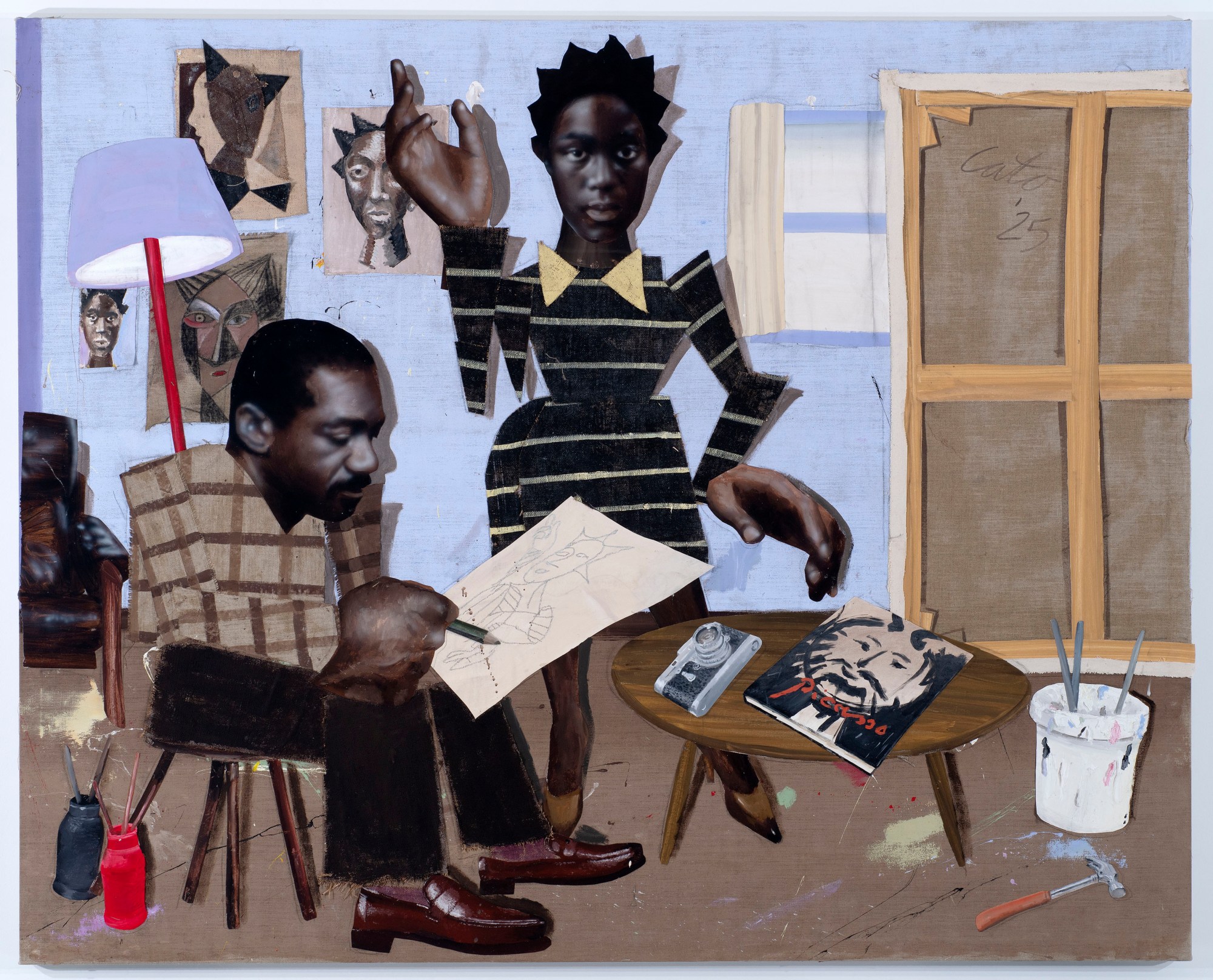

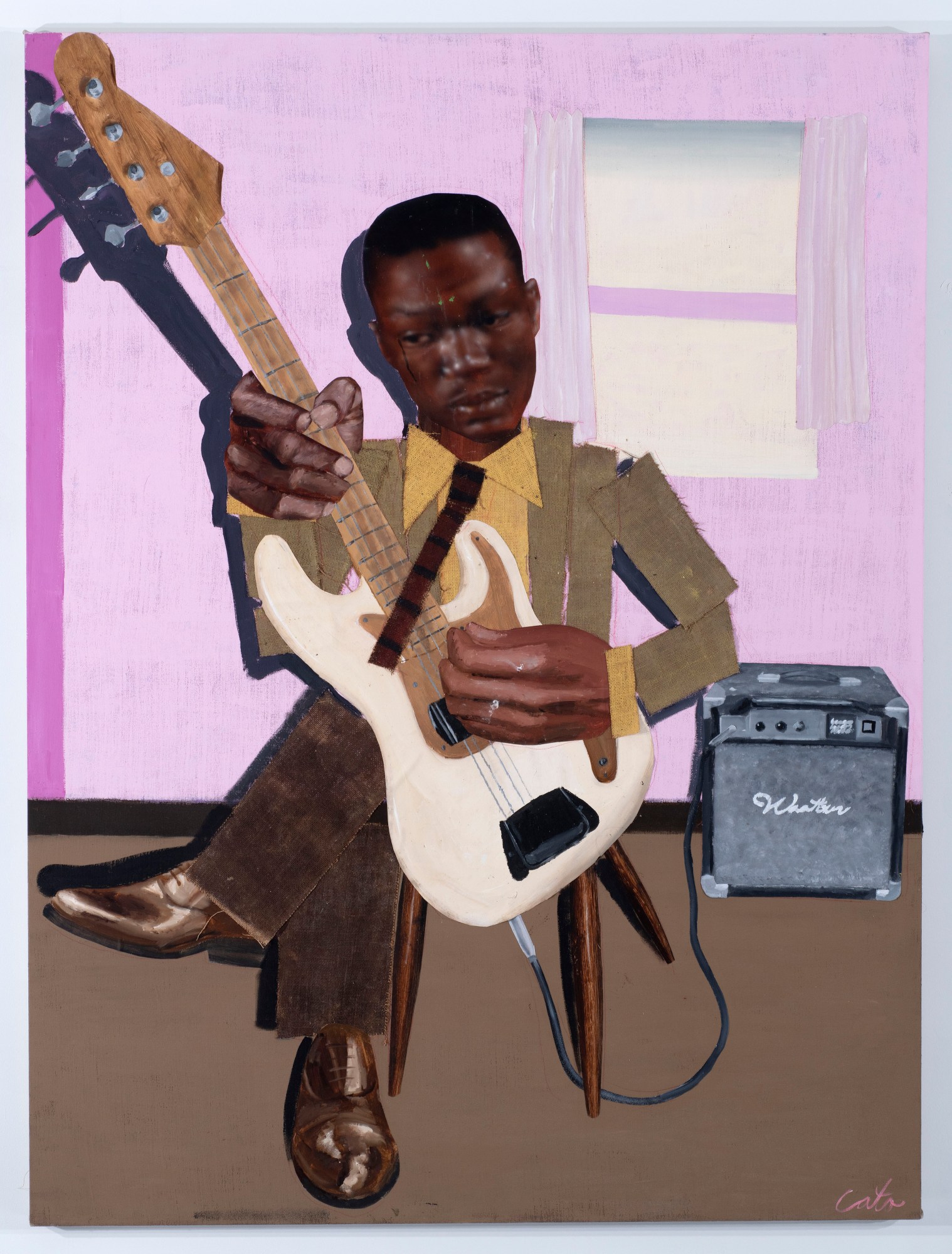

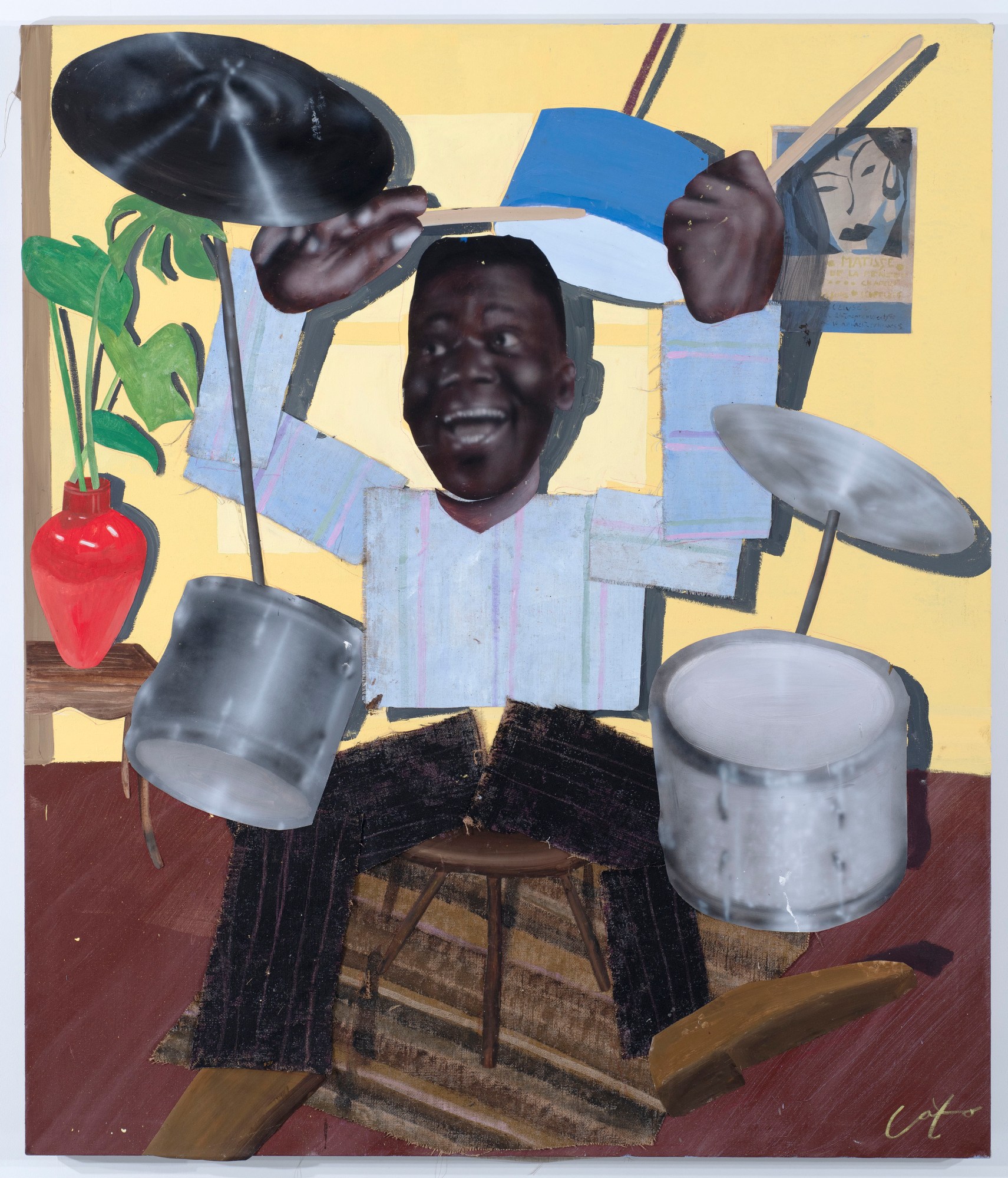

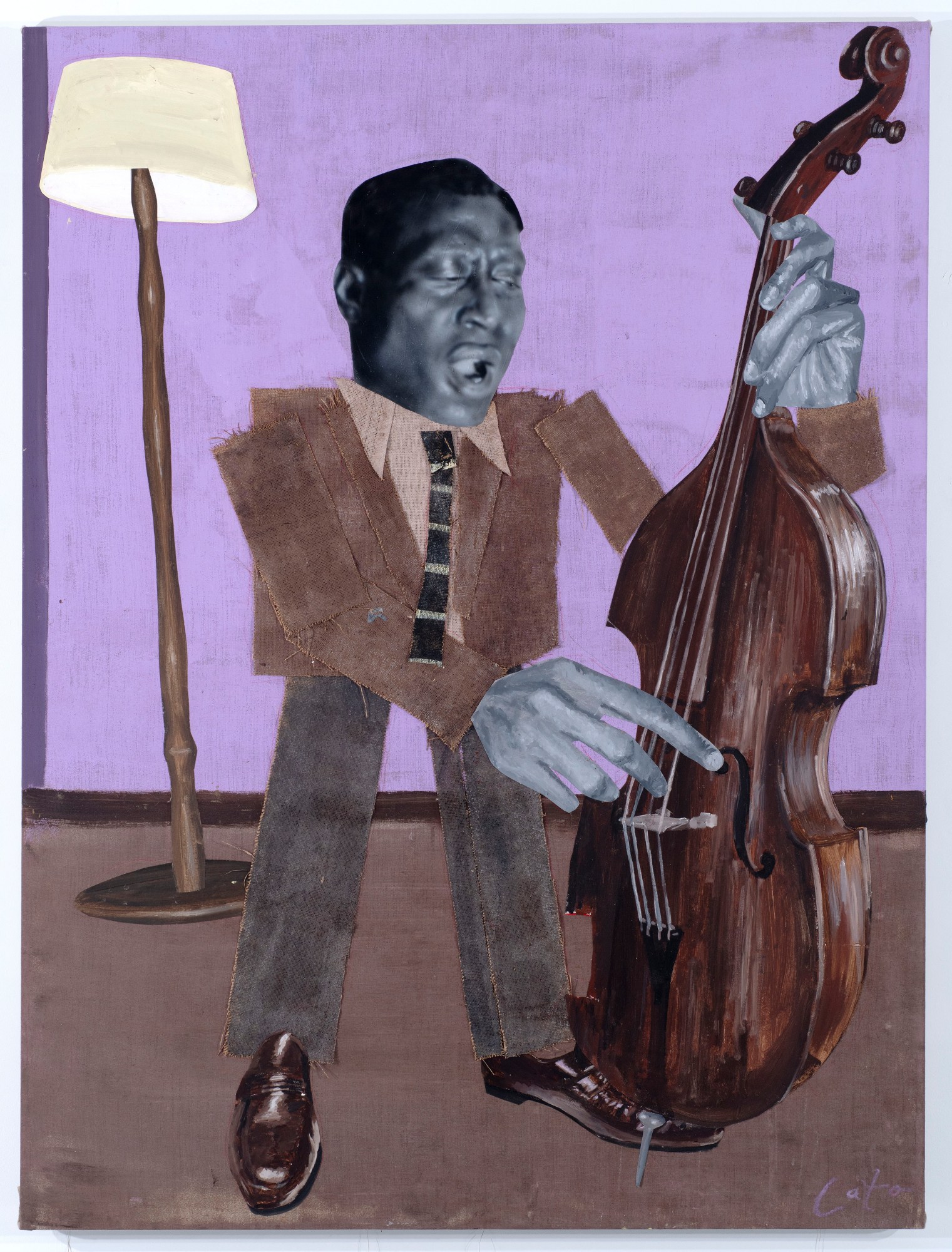

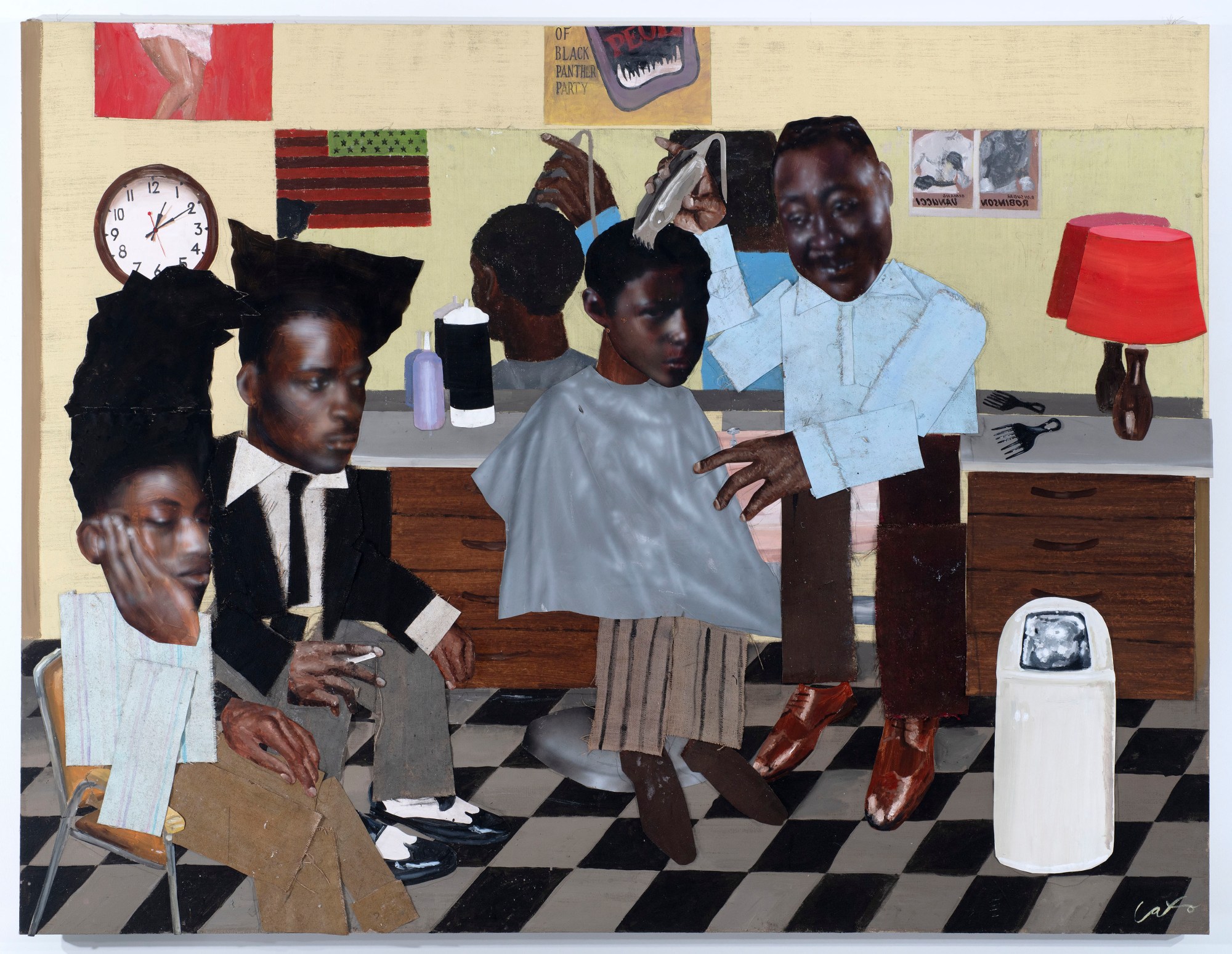

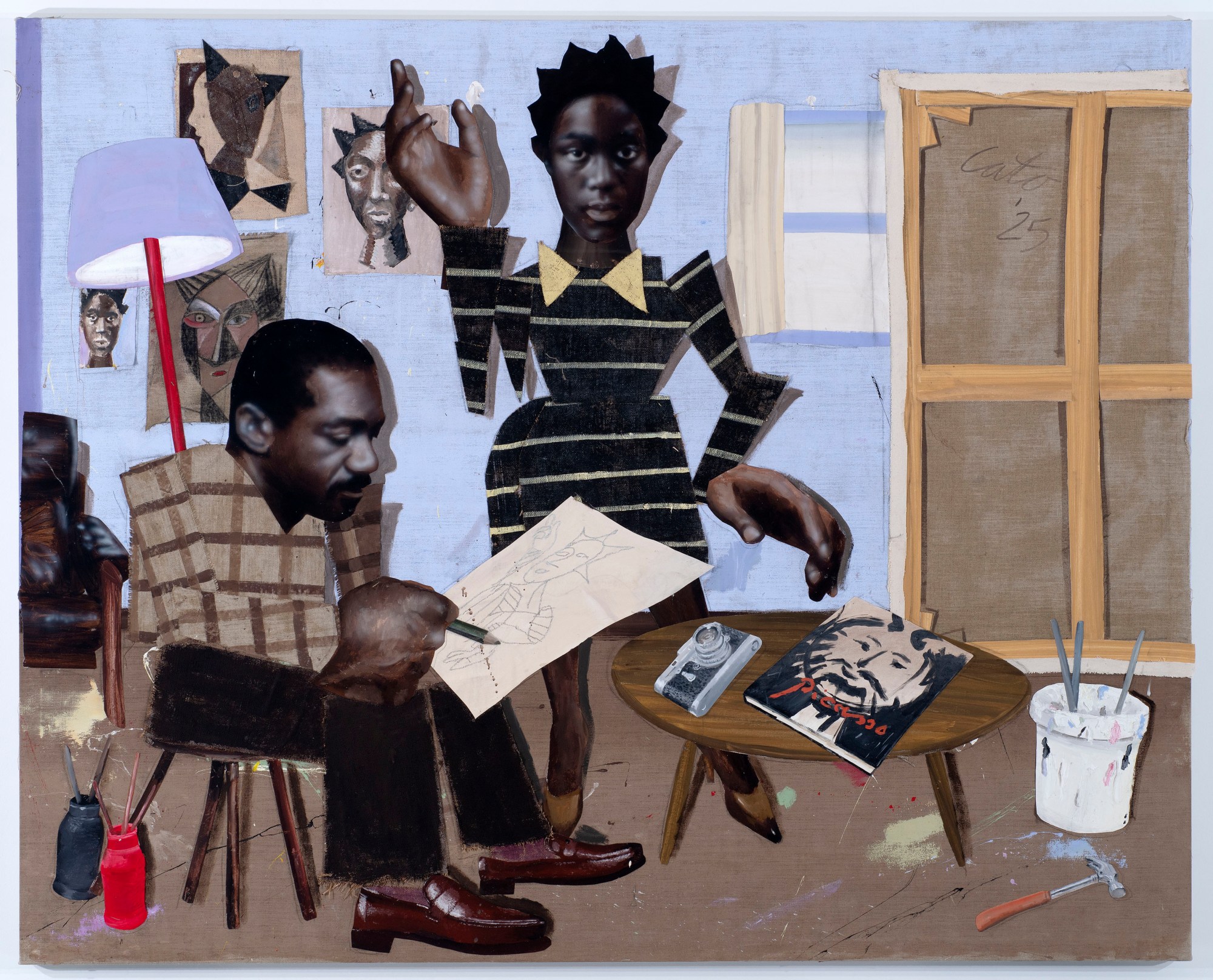

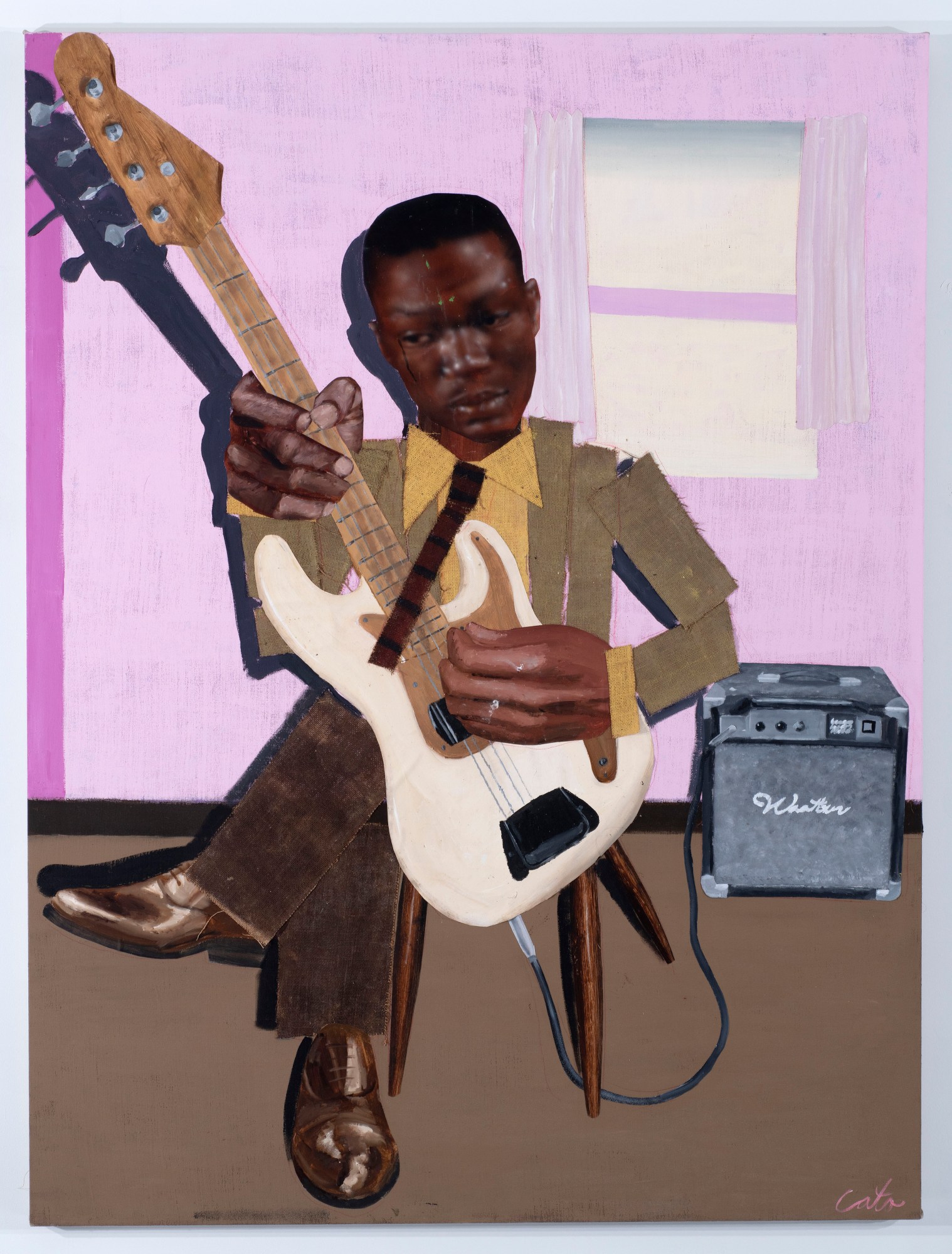

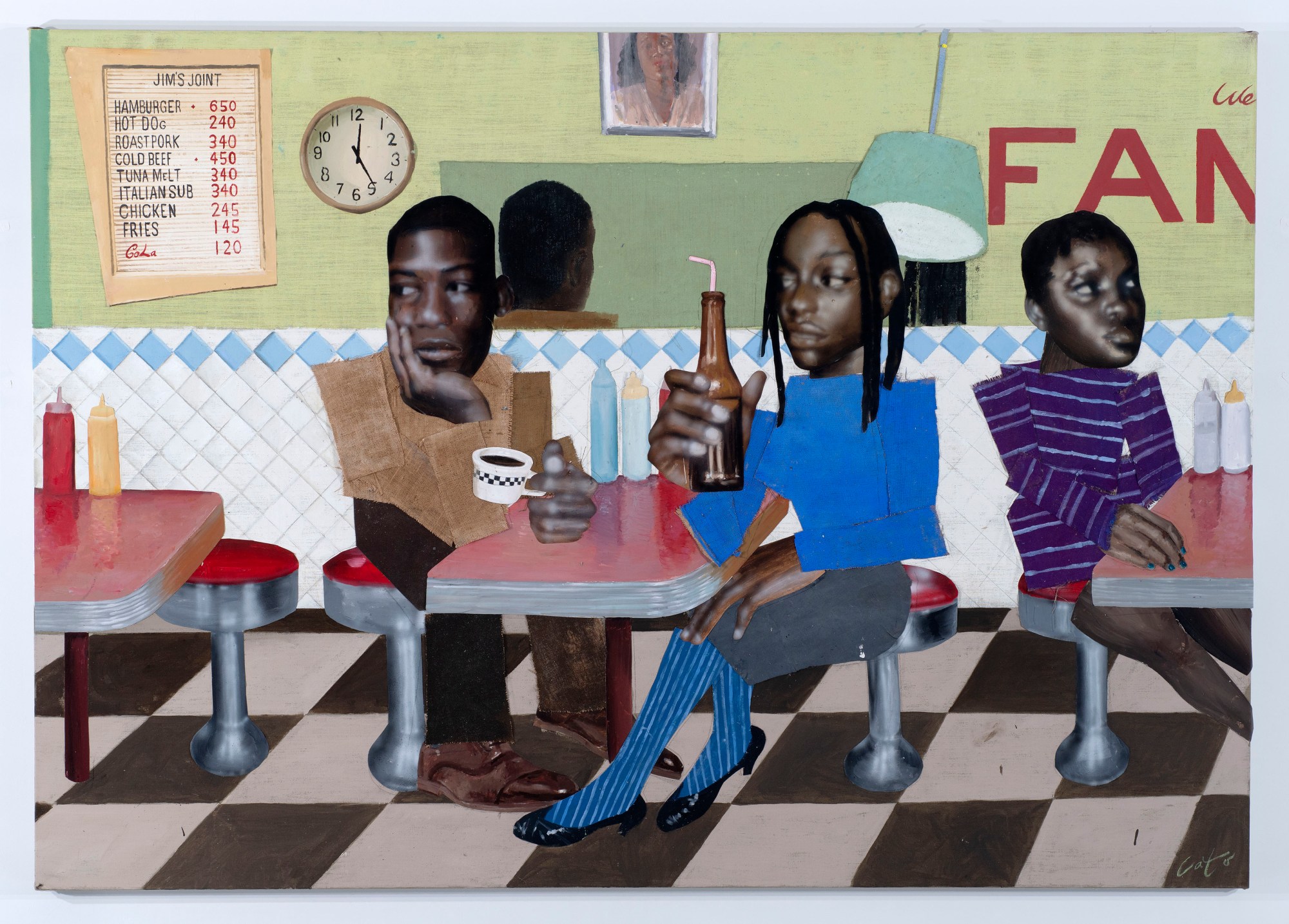

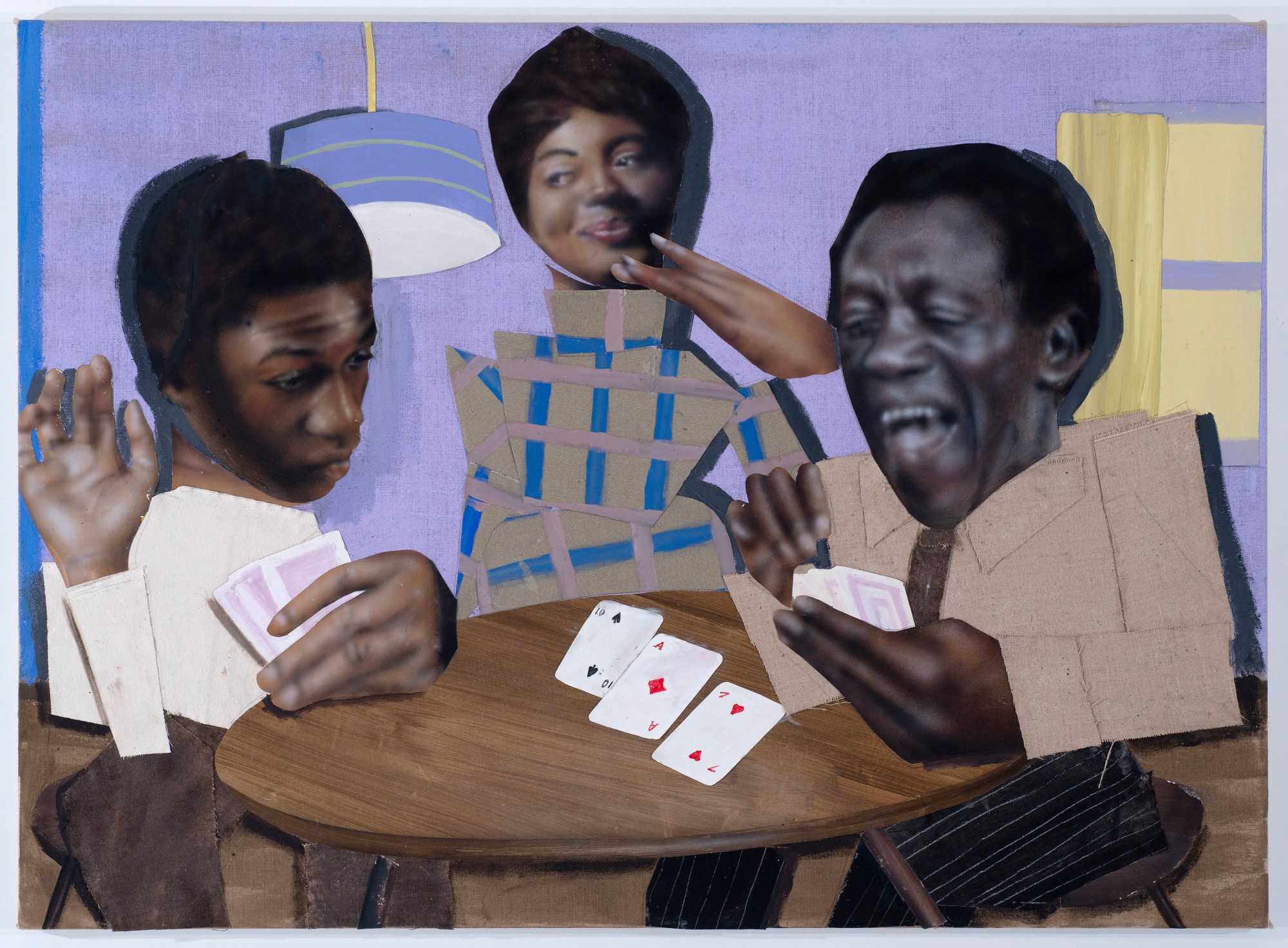

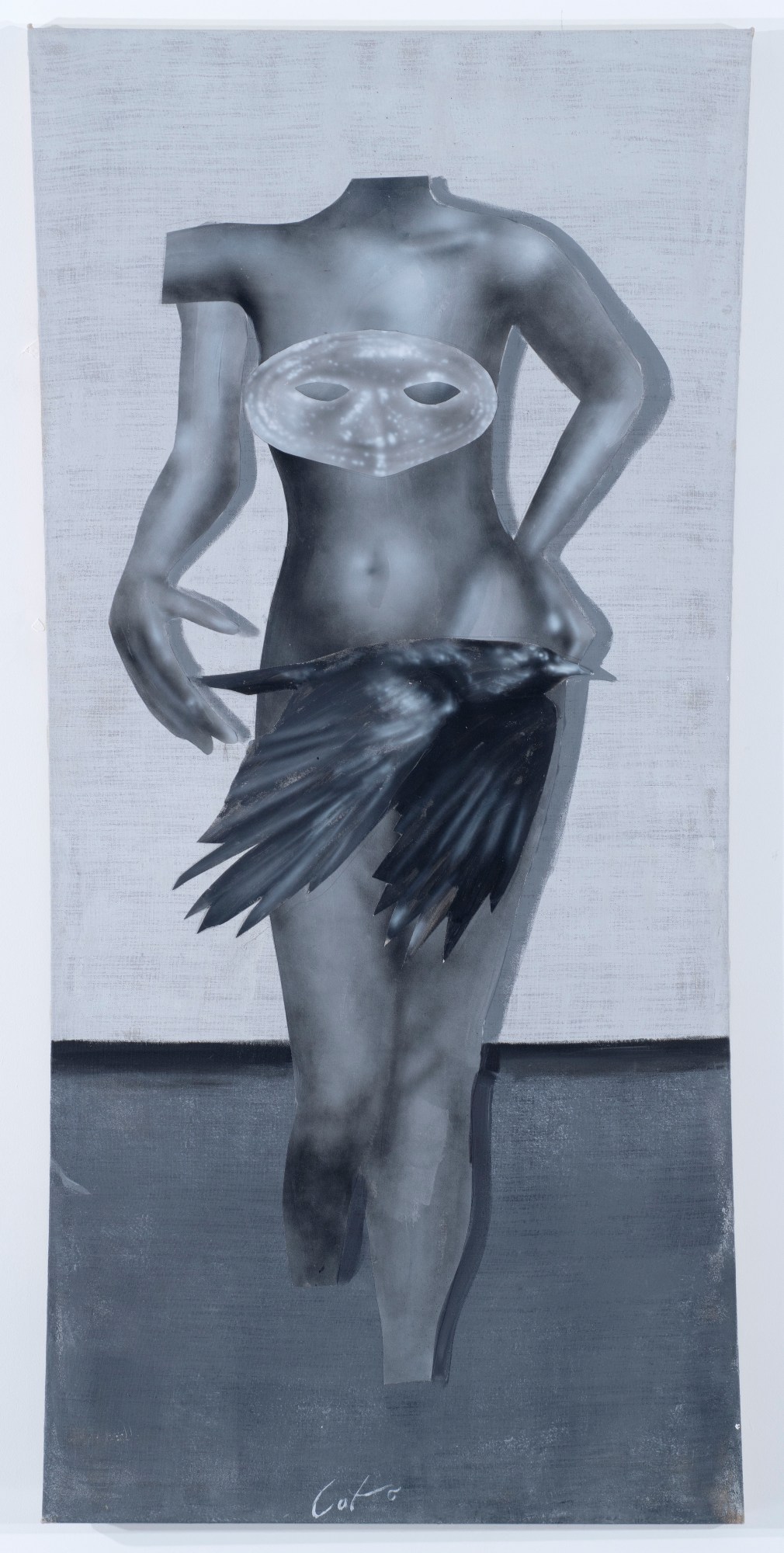

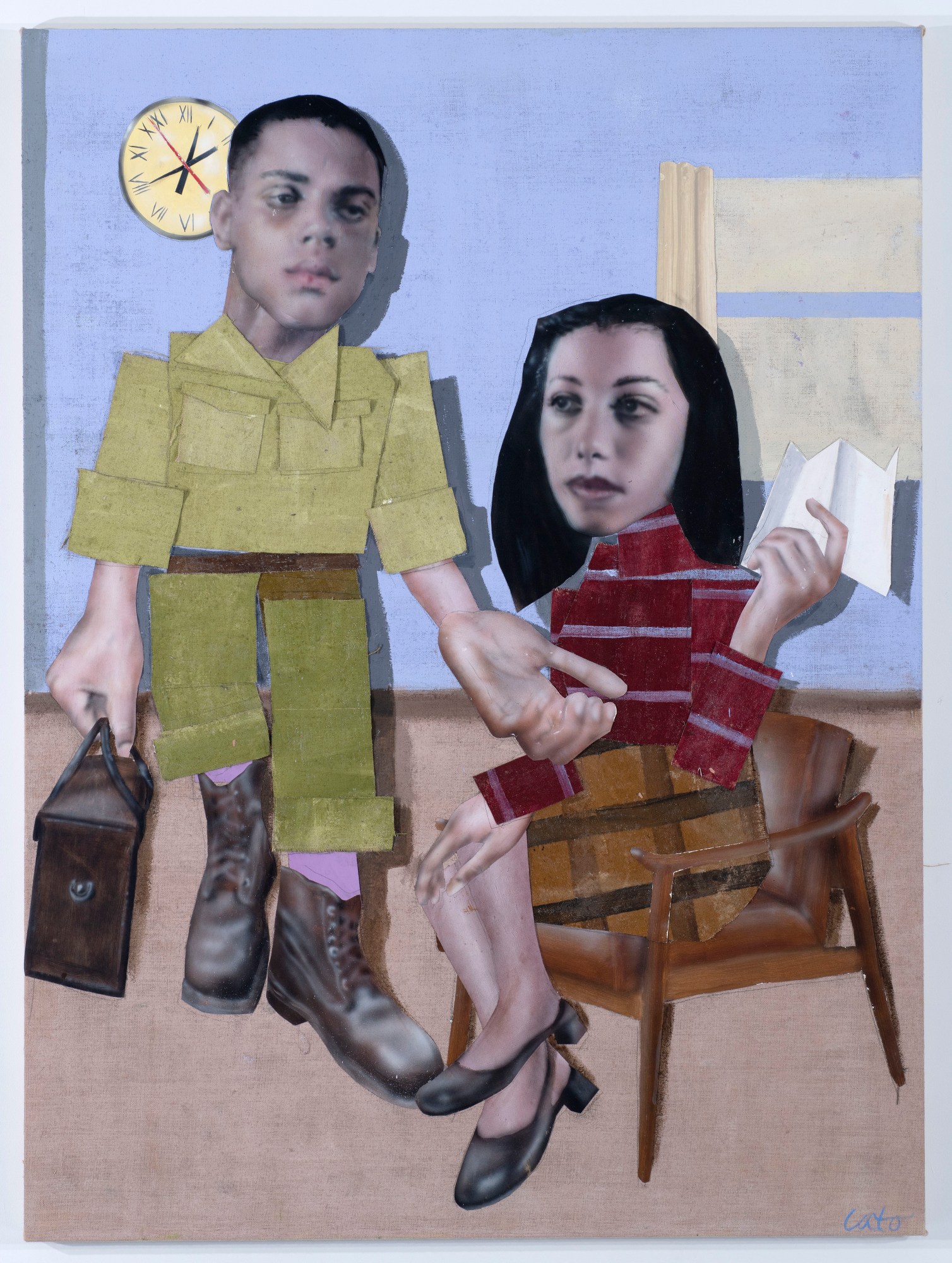

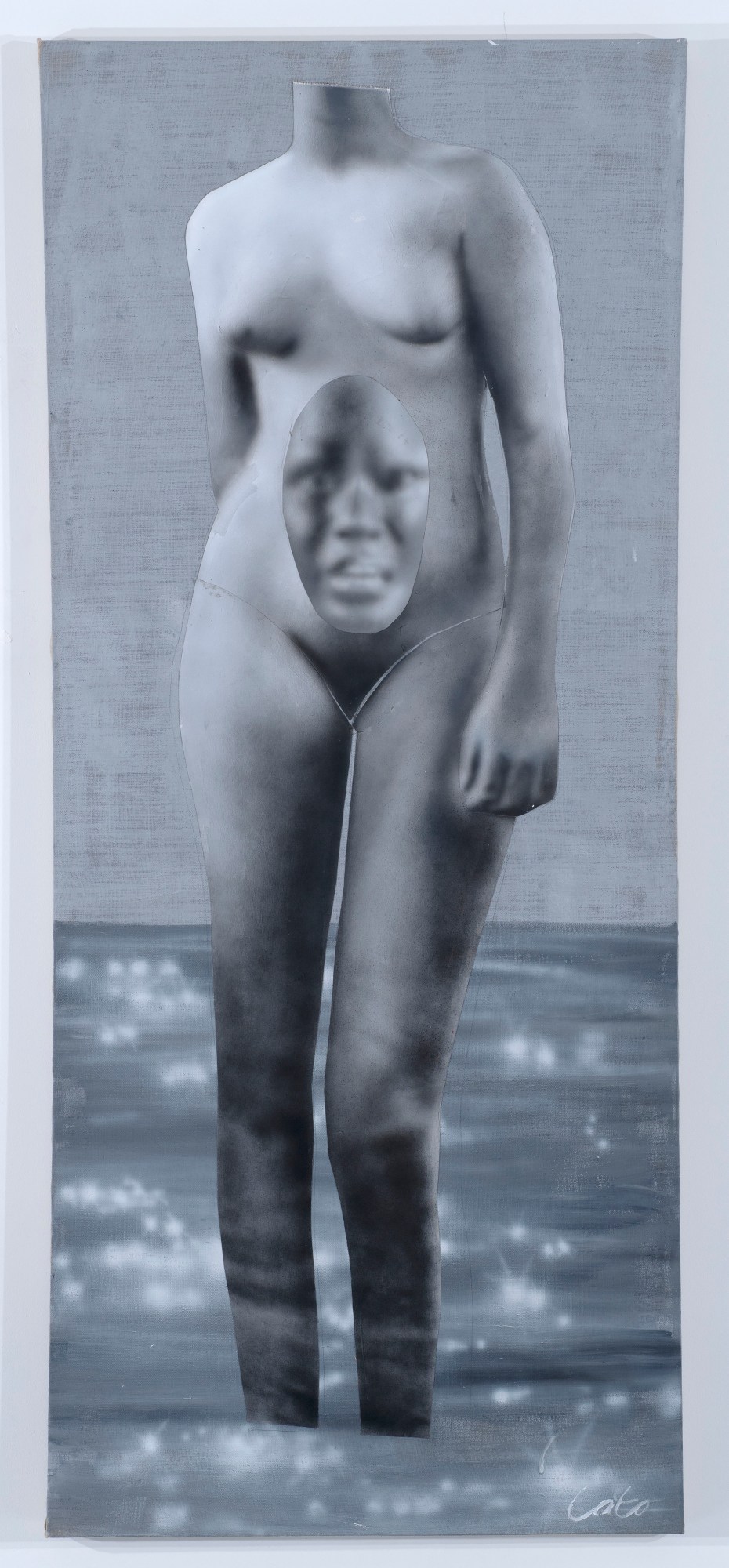

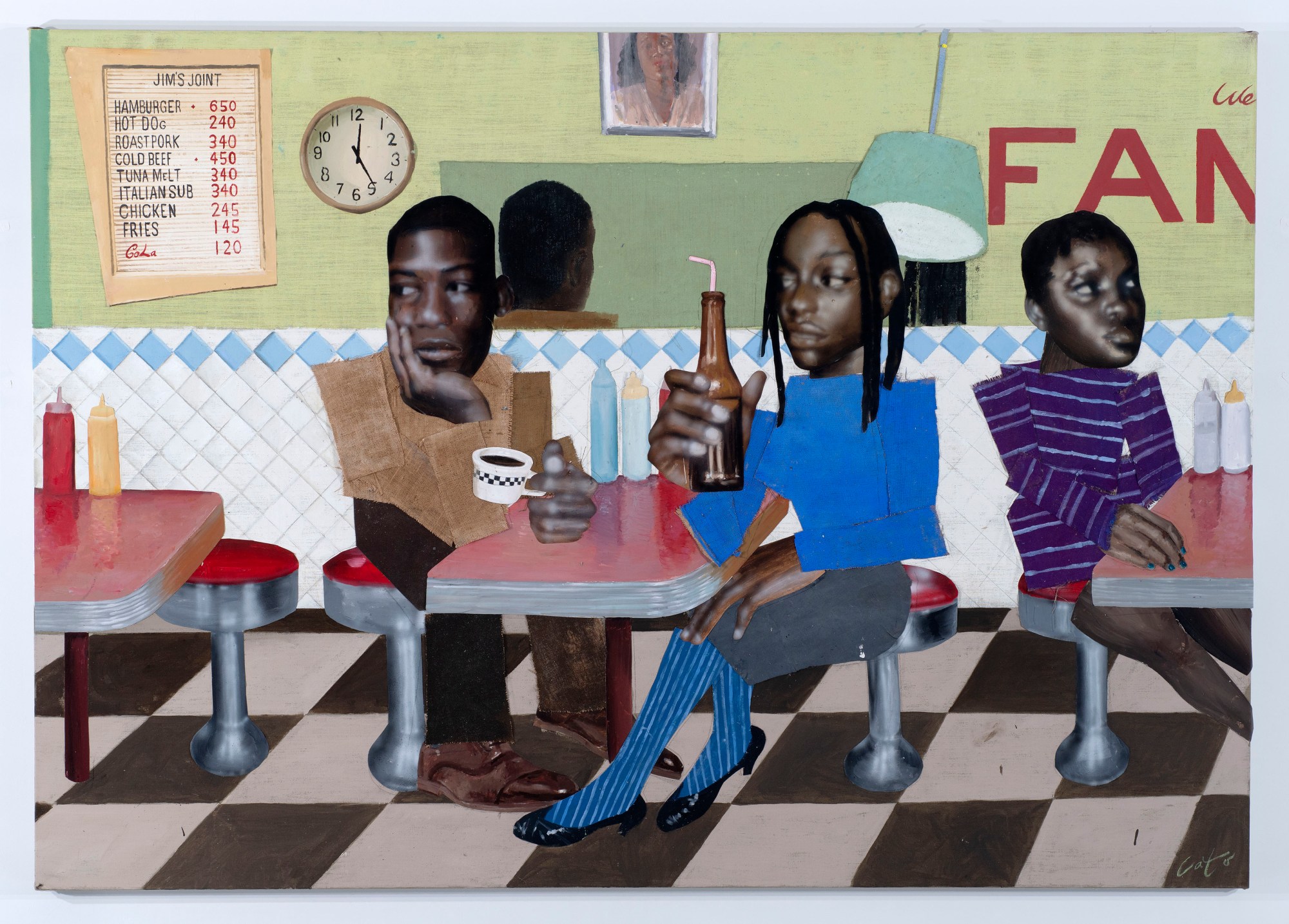

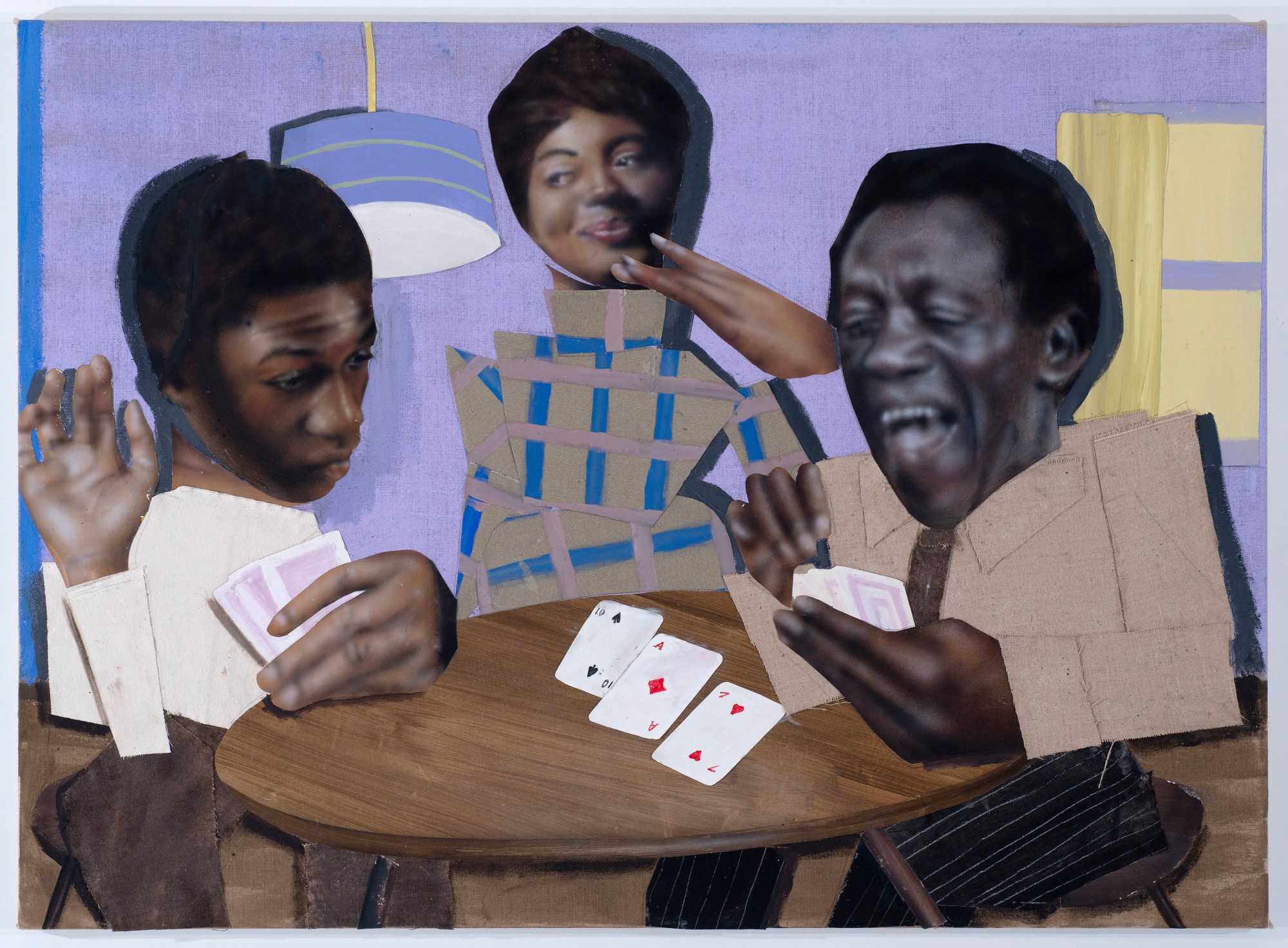

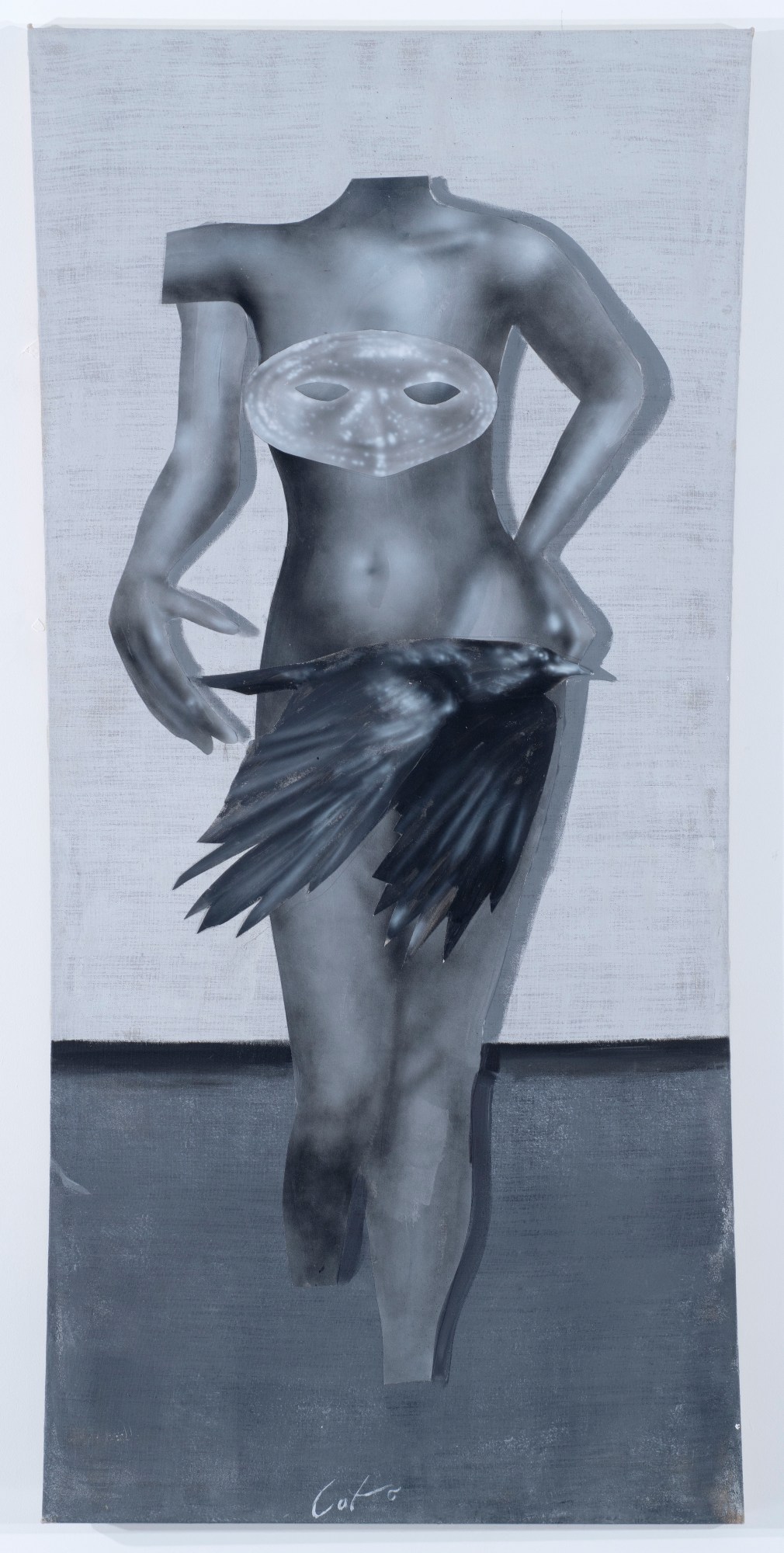

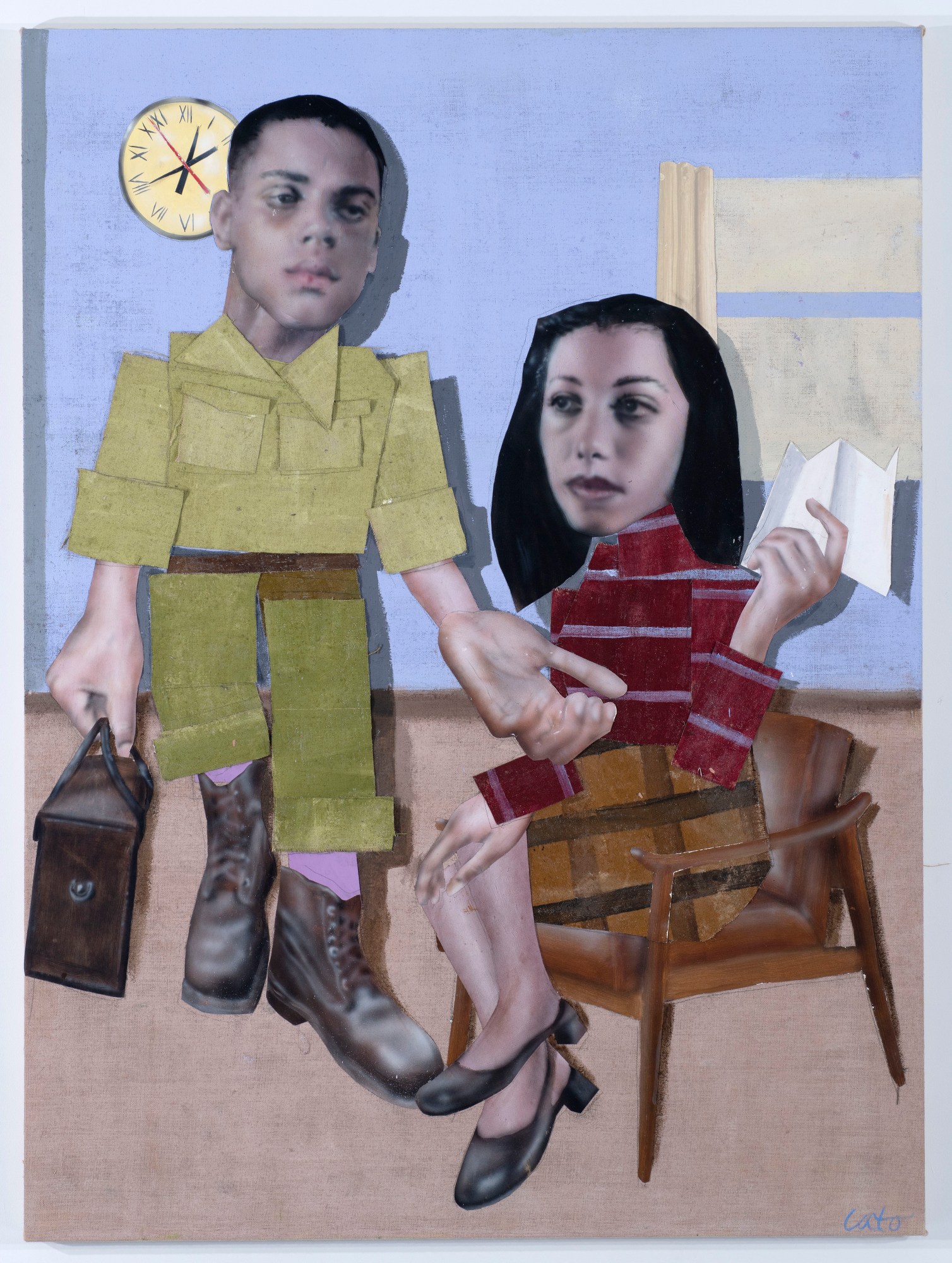

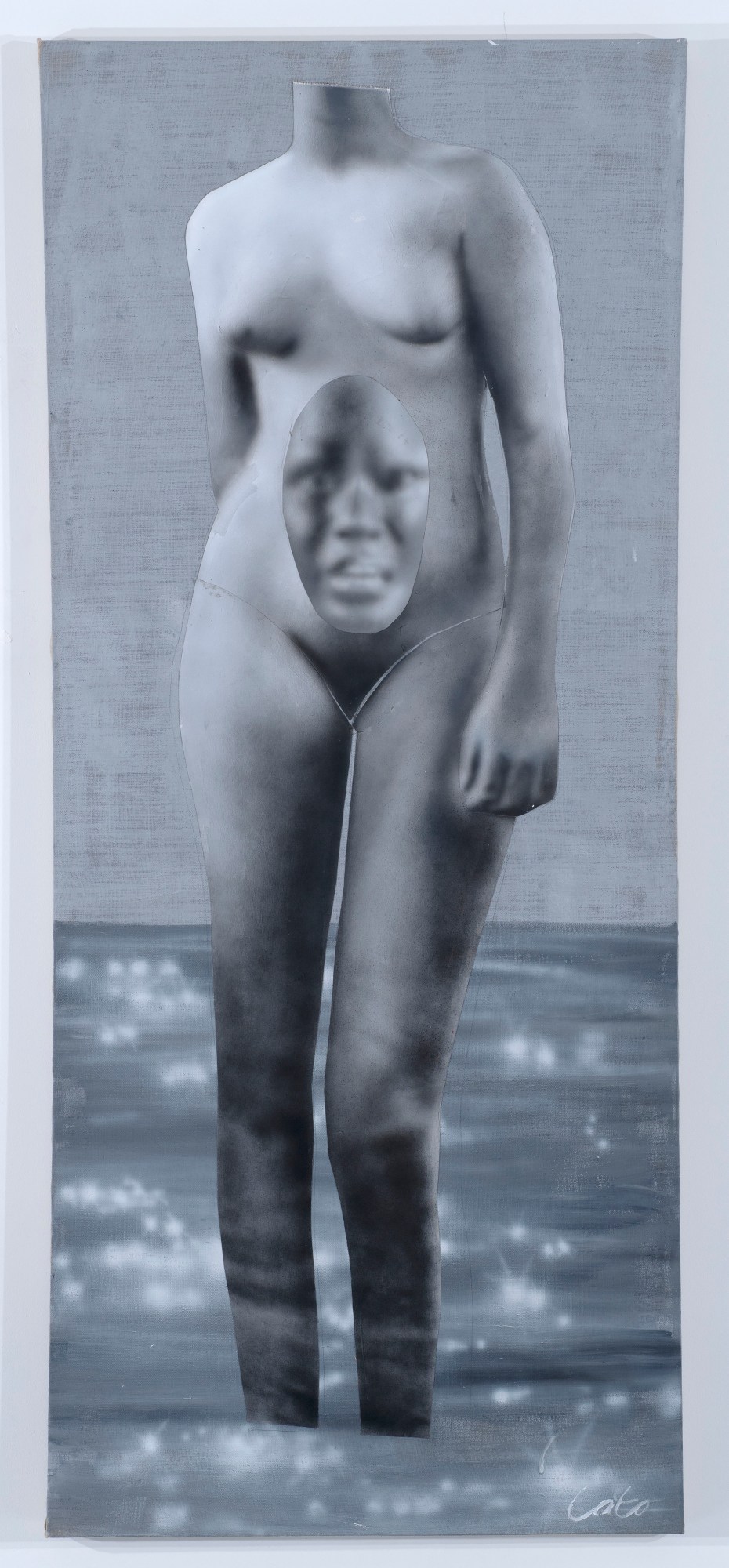

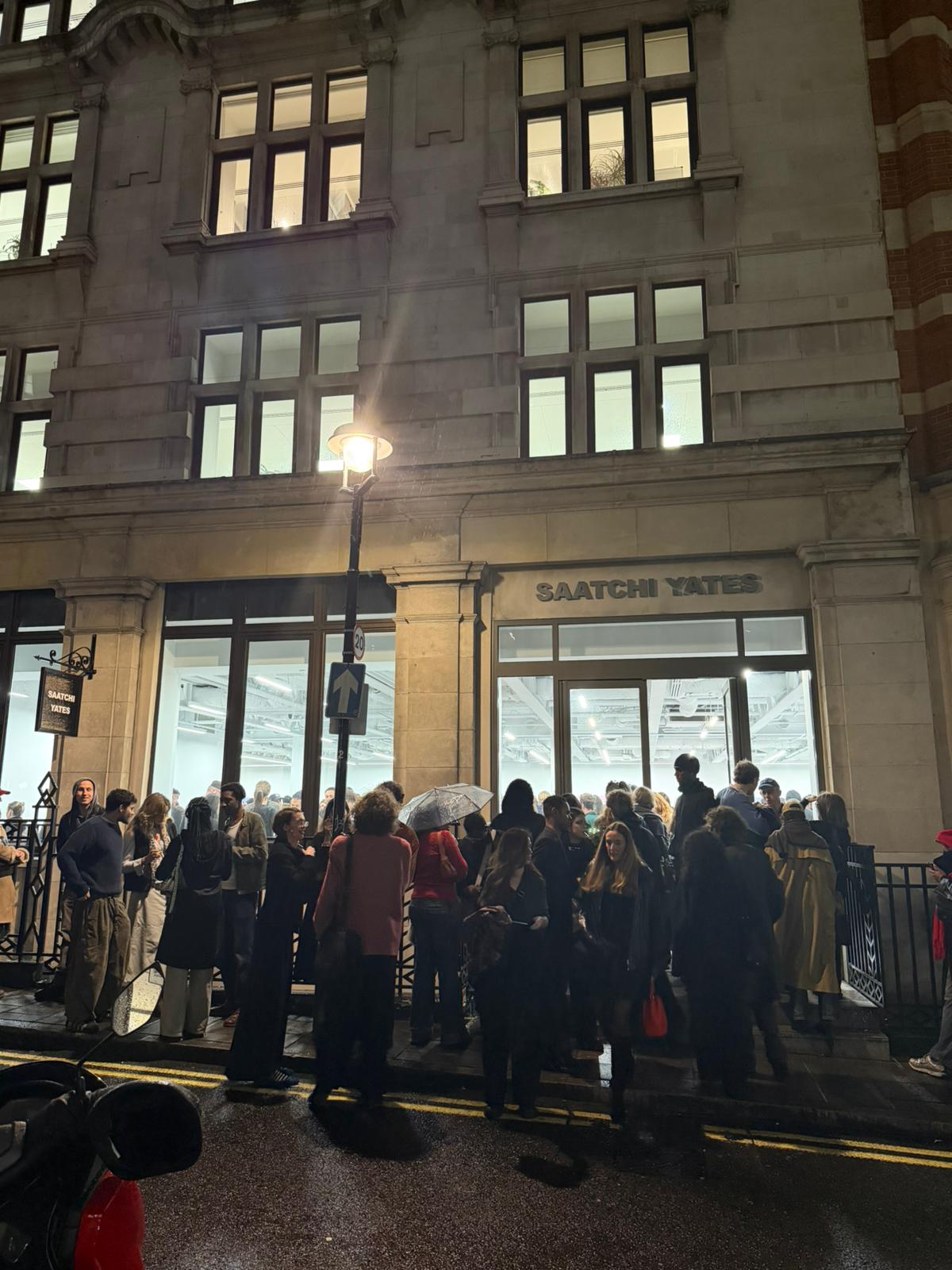

Cato’s new show at Saatchi Yates—his largest, most ambitious body of work to date—is a warm, vibrant portrait of imagined Black intimacy. Though many assume his scenes are rooted in South London’s real interiors, he waves that off. “They’re imaginary,” he insists. “It’s not me roaming around looking for subject matter. The people come first, and the world builds itself around them.” His canvases mix airbrushed softness with punchy, meticulous brushwork: elongated hands, expressive faces, dense interiors full of paintings-within-paintings, all rendered in the kind of saturated, cinematic color that makes each scene feel half-memory, half-dream.

He casts his characters in Peckham. There are strangers with expressive faces, people whose heritage echoes his own, sitters who seem to carry stories in their posture. One woman, Charlie, a friend of his partner Gloria, inspired the entire women’s hair salon painting. “She came once with braids, once with these crazy ringlets,” he says. “I realized, that’s the girl waiting to get her hair done.”

Two young Caribbean guys became the heart of the barbershop scene. “They reminded me of family,” he says. “And it felt good to bring them into my space—people who don’t always get told they can work for themselves, make art, be their own boss.”

For this show, he pushed himself technically. There are fewer airbrushed shortcuts and more traditional brushwork with richer, more complex interiors. “I’d fallen into a formula,” he admits. “Ambiguous backgrounds, simple worlds. Then I saw the Kerry James Marshall show and thought, if I go bigger, these worlds can get bigger too.”

The first of these large works, the barbershop, unlocked everything. “Once that one existed, I could breathe,” he says. “It gave me confidence for the rest. I made almost all of them within a month.”

Born Toby Grant in Brighton, but better known in the art world as Cato, the 25-year-old artist—known for distorted-yet-familiar portraits that stretch real life just enough to feel imagined—got his start when a young gallerist, Ronan McKenzie, spotted his early paintings and encouraged him to send works back to London. “That’s when I started thinking seriously about galleries,” he says. “It made sense. I could actually make a living making images.”

Before then, his life sounded mostly like a coming-of-age novel. Two older sisters. A radio-producer father who moved between BBC arts and science programming, wrote on the side, and grew up in a Jamaican immigrant family in Luton—complete with a grandfather resourceful enough to hustle together the money for a single term of private school. A mother who studied art but became a therapist, the type who hand-sewed dinosaur costumes and baked elaborate homemade cakes, turning creativity into something domestic and tactile.

“I was more into science at first,” he tells me. “Dinosaurs, biology, ancient history… That was my whole world. But my mum would draw things for me to color, and eventually I just started drawing on my own. I was always doing it, even in school when I was supposed to be taking notes.”

Art didn’t arrive as a lightning bolt. It folded slowly into his life, carried by family, made inevitable by repetition. By 14 he knew he’d end up doing something creative—maybe film, maybe drawing—and by 18 he’d realized the call center jobs he tried were not for him. “I’d end up drawing all over the call sheets,” he laughs. “So I promised myself to at least draw one thing a day just to keep the fear away. The fear of doing nothing interesting.”

He soon landed in Peckham at a graphics school and found a growing fluency in the programs he’d taught himself. Then, just before lockdown, a leap. Mexico City, to be exact. This was where an airbrush he picked up on a whim became the beginnings of the painterly language that defines his work today. “At that point I was making songs, animating, painting,” he says. “Three different mediums, one kind of output.”

Music was the other thread. In Brighton, he fell in with a group of friends who rapped and animated bizarre shorts together in the home of his friend Jago, whose dad was an eccentric animator. That house became a “creative hub,” a place where weed smoke, hand-drawn frames, and early songs blurred into each other. Cato learned animation there, too. Which became useful later, but ultimately too time-intensive. “Painting was always the dream,” he says. “Animation is beautiful, but it’s way more work.”

Before we log off, I ask what he’s been consuming lately. His answers feel exactly right. John Cassavetes films; Raymond Carver short stories; Bowie, Velvet Underground, that strange ’70s New York-London creative pipeline. “There’s always a duality,” he says, reflecting on heritage and identity, as well as the push and pull across generations and continents. Duality, maybe. But the worlds Cato paints feel whole.

Cato’s exhibition is open at Saatchi Yates, London, from November 2025 through 11 January 2026.