Anaïs Makouke’s essay “Karukera” is a love letter, plunging deep into memories from her childhood on the island of Guadeloupe. Originally named Karukera — or “the island of beautiful waters”— by the native Arawaks, the land now known as Guadeloupe was colonised in 1493 by Christopher Columbus before being claimed by the French two centuries later. Since then, the French government has failed to intervene in an island-wide health crisis caused by a pesticide used from the early 70s to the early 90s on banana crops. Now with one of the highest incidences of prostate cancer in the world, and with 90 percent of its adult population showing traces of the pesticide in their blood, Guadeloupe is home to a non-biodegradable poison that will continue growing in its soil for lifetimes.

While celebrating its majestic mountainscapes, bountiful fruit trees and magical nights teeming with the sounds of frogs, crickets and what many believed to be mystical creature, Anaïs’s essay is also a condemnation of the French government and a powerful call to action. Accompanied by photographs taken by Cécile S. Baudier, “Karukera” serves to shine a light on this violent injustice. Read it below.

You can’t see the poison, but you know it’s here. In our rivers, our soil and in the milk of breastfeeding women. We live with it but didn’t ask for it. Our government has benefited from our land and in doing so they have created an inescapable consequence that our bodies are paying for.

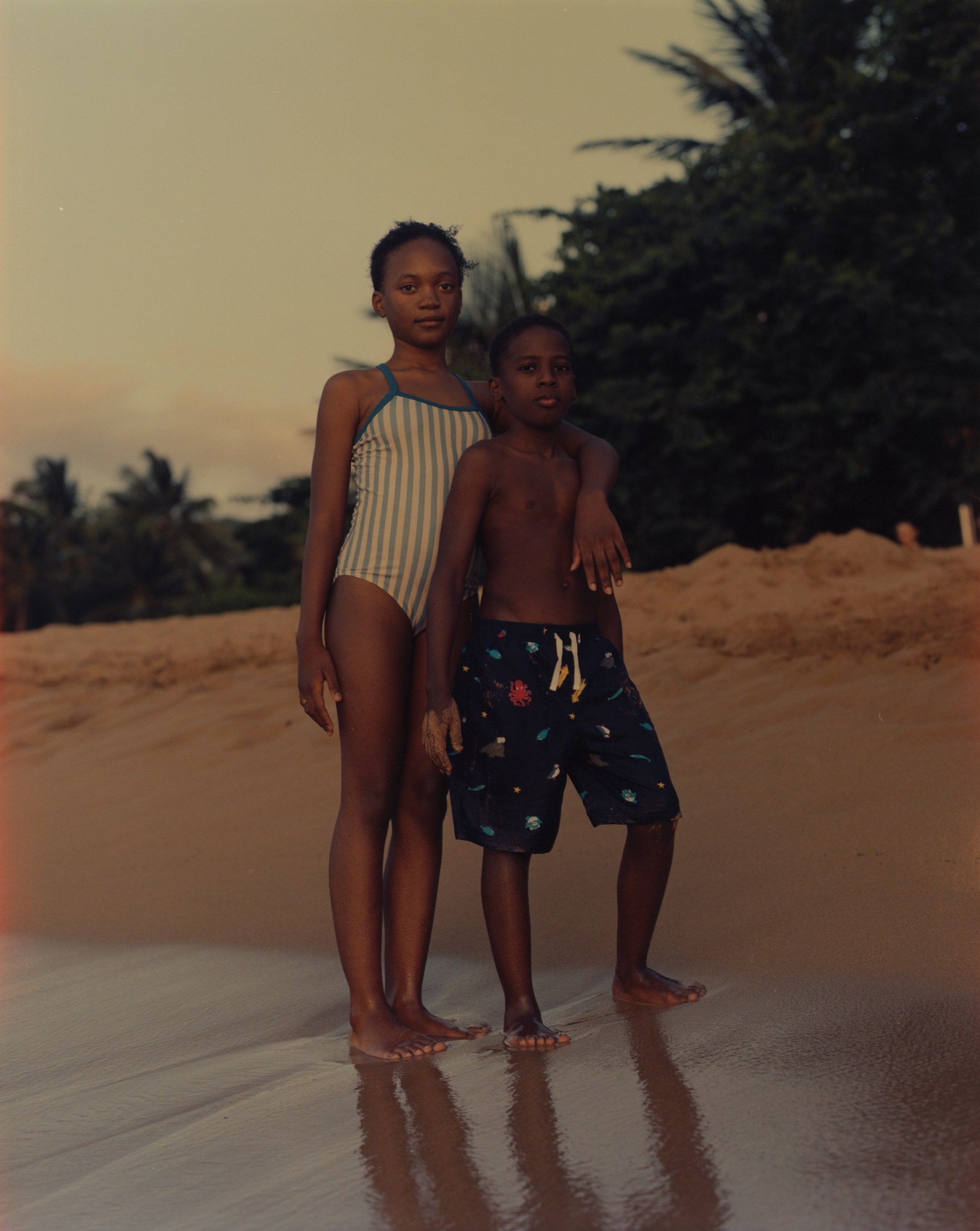

We don’t avoid infected mountain rivers or coasts by the sea. This is our home and we cannot move. To me this is what it means to be Caribbean. We know how to endure, because there is in fact nowhere to run. The ground we walk on and the waters we swim in is what nourishes our bodies and our souls. Perhaps this is why our relationship with nature is so deep and perhaps this is why the pollution of our island is so hard to accept.

For two decades from 1972 to 1993, Chlordecone, a pesticide directly linked to cancer, was sprayed on banana crops on the island, and now more than 90 percent of the adult population have traces of it in their blood. Guadeloupe has one of the highest incidences of prostate cancer in the world and because Chlordecone is non-biodegradable, it is likely to persist in the soil for hundreds of years. Looking around at the island you would never know.

Long, sandy beaches glow in the dark and the light at sundown paints everything blue. Here, in the middle of the southern Caribbean, sea clouds hover dramatically over the ground, making the distance between earth and sky appear closer here than elsewhere.

There is this notion that islands are small, but in fact all Caribbeans know that the discovery of an island is an infinite process. Forever subjected to natural events such as storms, cyclones, earthquakes and volcanic eruptions that transform and reshape our landscape. We are constantly at the mercy of nature.

From space, you see the island shaped like a butterfly. I grew up on the right wing, in a small beach town by the name of Sainte Anne, known on one hand for its mountainous region and on the other hand for its beautiful clear blue waters. The beach was more than a beautiful postcard, to me it was the cradle of my childhood.

I remember spending my days after school picking low-hanging gooseberry fruits and juicy, sticky mangoes from the trees on the savannah, as we called by the field where my father tied his animals. We were left unwatched and the only rule was to never wear red as it could upset the grazing bulls.

Each summer my grandparents would round up their six grandchildren into the open-top trunk of her beige Peugeot pickup truck, sticking us close together and telling us to hold on as our awkward tiny bodies bumped up and down as we drove down to the beach on rocky roads in the sunny afternoon light. We would spend the afternoon on the beach, laughing, fighting, screaming and jumping until sundown.

The nights are never silent here. They are loud, filled with sounds of cricket, frogs and spirits. If you’re not from here, the noises will keep you awake, scaring the life right out of you. We would lay outside on the terrace, telling each other stories, each one more frightening than the last, about Caribbean flying spirits and creatures, who exist only in the dark, half-human, half-animal.

Each year, at the end of our holidays, my grandmother would wake us up in the middle of the night with a cup of special herbal tea, bitter and dry. She said it would clean our bodies and our minds and that it would prepare us for a new year.

She would then place a huge basin at the back of the house, fill it with water and huge piles of green leaves. We waited with excitement as the leaves turned heavy and wet and I remember entering the basin in pairs of two, laying down beside my cousin, laughing as our bodies scrubbed against each other in the bathtub.

Reality and magic have always been entwined in our reality on the island. I learned the history of my family through the myths and traditions practised by my grandparents, but I learned the importance of nature from my father.

It’s five in the morning and I am meeting my dad, Cesaire, in the outskirts of the city, in a field where he is putting his cows out to graze. When I arrive, it’s already hot and I feel the sweat on my forehead as we are walking through the meadow. My dad seems to move without effort, running after the cows, dragging them each to their selected spots.

With his machete, he cuts off coconuts from one of the palm trees and we sit down on the wet grass to drink. “Working in nature is part of our family’s history, of our identity,” my dad explains. “I believe that work doesn’t kill you, on the contrary, it keeps you alive. Your grandfather lived off the land, planting pineapples and sugar canes. It gave him a job, but more importantly it gave him purpose and he taught me the meaning of work.”

I ask my father if he is worried about the pesticide pollution and he laughs nervously. “It makes me angry. I don’t know anything about products and I refused to have my land analysed. It’s been suggested, but I’m not interested. And if my land is polluted, what do I do? I’m not worried because I also know that I’ve used only a few products. I couldn’t afford to buy any”.

I understand my dad’s point of view. The truth is knowing serves little purpose, because we can’t do anything about it and and for most people in Guadeloupe, leaving is not an option.

I am part of a long and complicated European history, but it is the government’s acceptance of our bodies being poisoned for years and years that has awoken my sense of patriotism and my identity as a Caribbean woman. I am French. A mix of Asian, African and European DNA. One identity does not rule out the other. I can be all of the above and the history of my island confirms this notion. That is the complexity of the Caribbean identity.

Credits

Photography Cécile S. Baudier