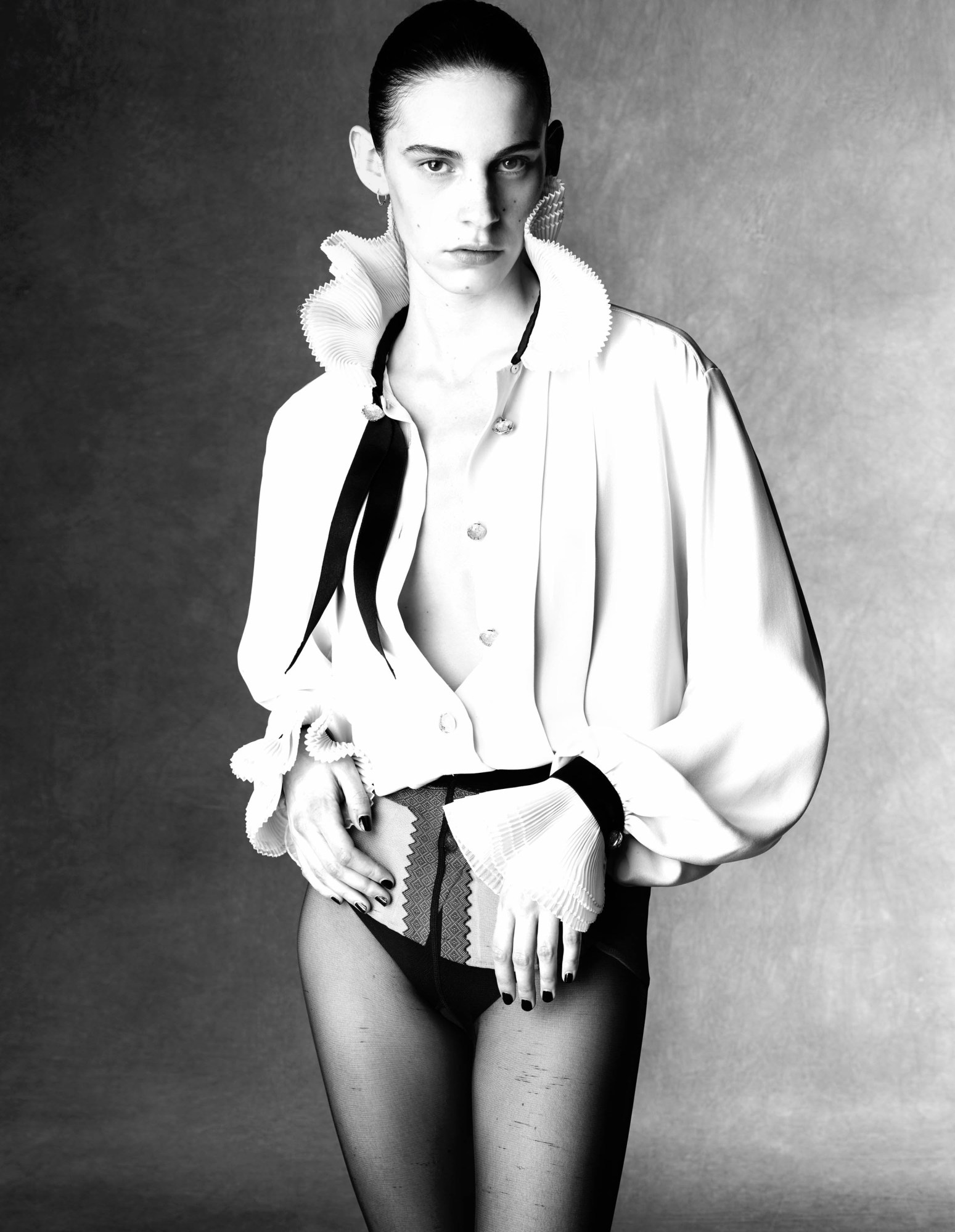

This story originally appeared in i-D’s The Icons and Idols Issue, no. 359, Spring 2020. Order your copy here.

Lesage, Massaro, Lemarié, Michel, Lognon, Goossens. Ever heard of them? They’re not French footballers and, no, they aren’t faceless European Union bureaucrats. In fact, these are some of fashion’s oldest and most fabled names, on a par with the legendary couture houses of the 20th century. They are just a few of the one-of-a-kind fournisseurs – or luxury suppliers – to the world of haute couture, each one a specialist artisanal workshop meticulously devoted to the sartorial minutiae of every button, brooch and shoelace you see on the haute couture catwalks in Paris. They are the feather twisters, silk pleaters, master embroiderers and glove crafters. They are the teams of people who bring the visions of fashion’s great architects to life. And if you are unfamiliar with them, you will have definitely have heard of their almighty owner: Chanel, for whom these ateliers are the jewels in its crown.

The French house, arguably the most robust torch-bearer of haute couture in the modern age, is the custodian of the last traditional ateliers in Paris. That is no coincidence. Chanel actively came to their rescue as they teetered closer and closer towards extinction. It recognised the importance of safeguarding the future of these workshops in order to protect itself, because without all those ateliers, there would be no haute couture – and without haute couture, there would be no Chanel. The dream of fashion would die, and with it the pride of a nation and its world-renowned savoir-faire.

So, under a subsidiary called Paraffection (which translates to ‘for love’), Chanel ensured the survival of 13 of its artisanal suppliers and 21 manufacturers, starting with button-maker Desrues in 1985 and, as recently as 2013, investing in Barrie, a cashmere mill in the Scottish Borders, preserving more than 200 local jobs in the process. The idea is that although Chanel owns them, they are available for hire to any other fashion house or designer that chooses to use their services, even if that’s a competitor. But Chanel is by far their biggest patron – and always has been, right back to when Coco was around – and in 2002, the late Karl Lagerfeld devised a genius way of showing that talent off: the annual Métiers d’Art collection.

Borne out of desire to showcase the handiwork of these precious houses (and to ensure they are not just ornamental), the Métiers d’Art sits somewhere between haute couture and ready-to-wear, as Chanel’s equivalent to Pre-Fall. Its most recent was the first of its kind designed by Virginie Viard (who Lagerfeld long described as both his right and left hand), shown at the Grand Palais in Paris. And if Virginie’s collection of sinuous pencil skirts and mottled tie-dye-effect denim feels younger than usual, that’s because it is in more ways than one. It isn’t just a new aesthetic. Under the watchful eye of Chanel, a new generation of craftspeople have joined the ranks of the highly skilled artisans who are the essential components of Chanel’s collections. No longer are fashion’s petite mains just little old grey-haired ladies (although there are still plenty of them, and their skill is indispensable). Kids are getting into couture, too. A new generation of craftspeople are preserving the techniques and traditions that have been whispered between generations.

That hasn’t always been the case. Decades of deindustrialisation in France drove a younger generation to aim for formal education and white-collar jobs and, as a result, the pool of available artisans for domestic production diminished. It wasn’t cool to be a craftsperson – why would it be, when you could be a designer or a stylist? But that is less and less of an enticing prospect as more information makes it clear that fashion is one of the world’s worst polluters. Simply making more clothes is not the answer. Making them better, however, is a step in the right direction.

You could say the ‘Made in France’ movement is on the rise once again, and artisanal apprenticeships have never been more in-demand. A counter-movement to mechanised, globalised production has brought many traditional, craft-based businesses back from the brink. Next year, Chanel will open the doors to its 25,000-square-foot building in Aubervilliers, on the outskirts of Paris, which will house all 11 of its ateliers under one roof, creating plenty more jobs in the process. William Morris and John Ruskin would be proud.

“We don’t know mass production here,” asserts Priscilla Royer, the creative director of Maison Michel, which has been making every sort of hat and head-topping confection since 1936. Royer is among a younger generation of leaders in the metiers encouraging young people to take up apprenticeships, of which there are two types: hatters (those who sculpt the silhouettes with the linden wood moulds) and milliners (those who apply the flourishes). “We have more and more young people who want to learn how to use their hands, to learn how to work with materials, which is important as everything becomes so digital,” she adds. Take the 22-year-old Irène, for instance, who joined Maison Michel from college. An avid milliner (she won hat-making competitions at school), she says that most of her friends are interested in becoming photographers or stylists, and fail to see the importance of being able to make something by hand, from start to finish.

“I find it quite impressive to see someone who can do that, to make something from A to Z,” she says. “And it shouldn’t be lost – it can’t be lost.”

Next door is Chez Massaro, the custom shoemakers which opened its doors in 1896. Its white-walled space is dotted with worn-in wooden benches surrounded by heavy-looking tools and stencils of metallic leather. The sound of iron hammers clamouring away fills the air. Two of the star apprentices of the studio are former philosophy and art history students, Abel and Paul, who left their academic studies to pursue work with their hands. It takes them about anywhere between two days to a whole week to craft a single pair of boots from countless hand-cut composites, always starting with a beech-wood last. Although they’re currently constructing pairs of strappy gold Chanel sandals for the catwalk (in the late 50s, Massaro developed those two-tone beige and black pumps with Coco herself) they’re less interested in the glittering world of fashion and more concerned with changing the world one shoe at a time.

“There is a trend in slow food and slow fashion, where consumers are becoming more interested in the conditions of production and want things that can be traced back to the craftsman,” Abel points out. “There are two sides to it, which is that on a technical level, things are being lost because there are fewer people who can afford it, but on an ecological level, there are more people who want it.” It presents a paradox that faces most people when it comes to sustainability. Buy less, buy better – or buy more for less.

“Currently custom shoes are a luxury product and there are very few people who can afford to buy them, but what we have seen is that standardised and industrialised production comes at the cost of standards of living,” Paul adds. He touched on an important question asked by millions as part of the Fashion Revolution’s viral campaign: ‘Who made my clothes?’ Six years after the collapse of the Rana Plaza factory in Bangladesh, which killed at least 1,132 garment workers, fast fashion is still being made by some of the poorest, most overworked and undervalued people in the world. In these ateliers, everyone is respected for their skill, paid fairly and given time to create the perfect product. And ultimately anything that is made in fewer quantities in a more humane way is ultimately of a higher quality for both the consumer and the planet.

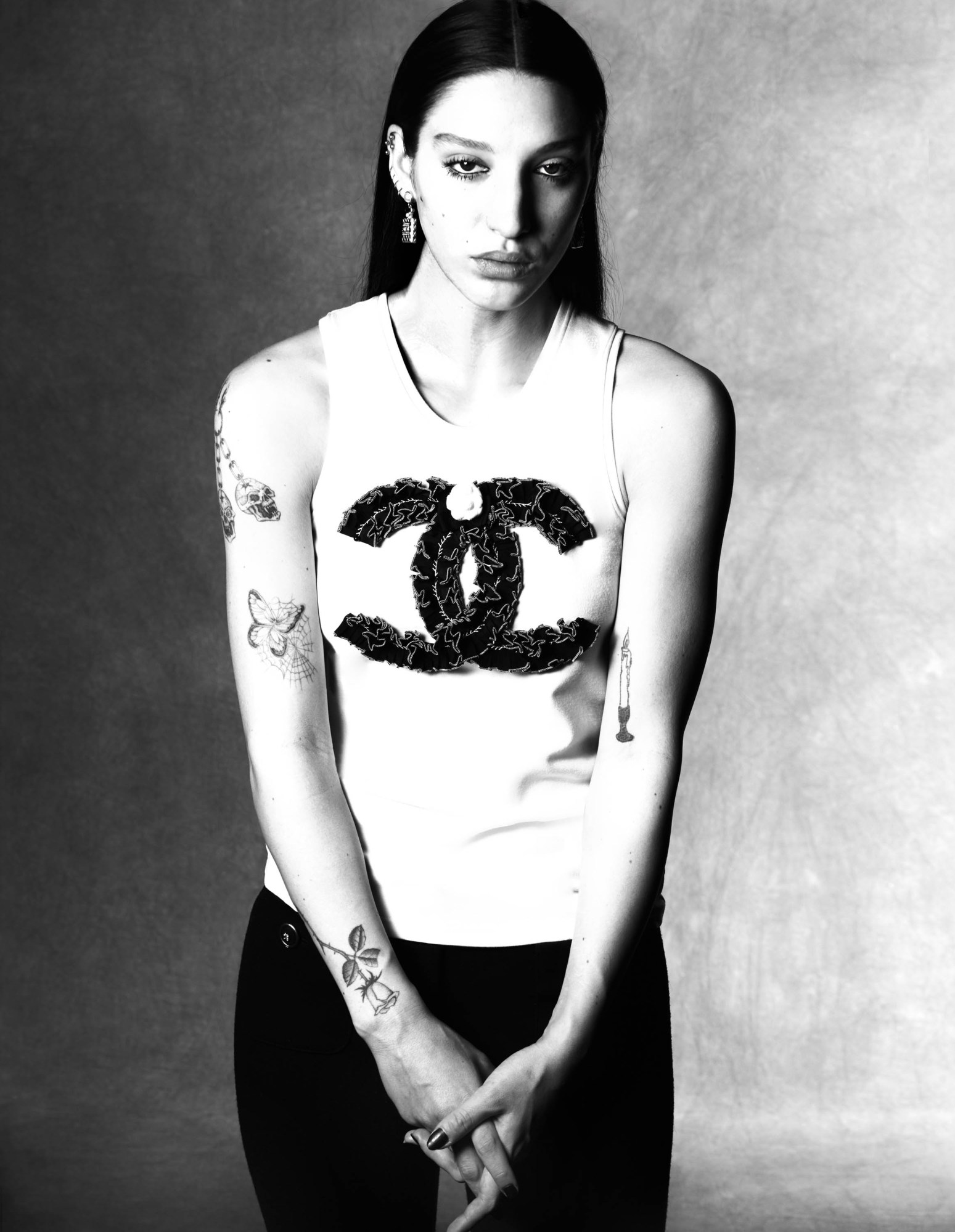

With younger pairs of hands also comes innovation and ideas. The idea of a passive craftsperson, there simply to execute the visions of designers, is very last century. Today, the craftspeople are able to suggest designs and materials, creating a dialogue between fashion and craft. “The profession has evolved and the people who choose to do this job have also changed,” points out Eléonore, a 28-year-old craftsperson at Lemarié whose rose-and-skull tattoos couldn’t be further from the workshop’s delicate artificial flowers and feathery trimmings. Lemarié was once among 300 ateliers that supplied feathers to Parisian milliners and dressmakers at the turn of the 20th century. Today, it is the last of its kind, bolstered by the fact that it now makes every single one of Chanel’s iconic 16-leaf white camellias, including each one pinned to its monochrome carrier bags in boutiques around the world.

“What is so nourishing is that there are people who are in their fifties or sixties and there are young people, and we don’t consider the work in the same way,” Eléonore adds as she precariously hand-curls a silk camellia petal – which will eventually, along with its fellows, cover a bomber jacket – with a heated roller. She considers her work as even more important because it is so rare – an older generation, she points out, may be more blasé about it. “It’s really about the idea of perfection, and how far we can go in the thoroughness of every detail, right up to the last centimetre and millimetre on a flower.”

It’s also about the creativity that comes with an intrinsic understanding of how things are made. At Lesage, the master embroiderers with over 75,000 quilted leather boxes of swatches from its 90 years in business, a creative team of young embroiders are even charged every season with suggesting innovative ideas to fashion houses. “Sometimes we’re crushing things or melting things, using different techniques for Plexiglas or metal or wood,” explains Flett, a British 32-year-old who discovered the house while studying textile design at the Royal College of Art in London. Within a year of graduating, she moved to Paris to work on developing Lesage’s embroideries for the likes of Chanel, Dior and Valentino.

The fashion houses send over creative briefs, which may be a watercolour painting or a mood, and the Lesage ladies (90 percent of the team is female) subsequently rifle through the endless brown paper bags of sequins and beads to come up with ideas for the 100 new samples it produces for each couture collection. “We have all those boxes full of thousands and thousands of beautiful, traditional embroideries, so they don’t always need us to create another one,” she adds. “The challenge is to come up with something that’s novel and different and hasn’t been seen before. The challenge is to create something modern.” An ancien régime this is not.

Of course, all that sewing, hand-rolling, and hole-punching on pieces of tracing paper to intensely map out where every bead, plume and hand-crafted flower will sit, eventually comes to life in the Chanel studios, before waltzing down the catwalk and appearing in the pages of magazines like this one. Everything you see passes through human hands – some old, some young. “Ultimately, they’re going to be the masters,” notes Maison Michel’s Pricilla Royer, reflecting on the young people in the various Chanel workshops. “They will be the ones protecting all this for future generations one day.” In other words, the future of fashion – and indeed Chanel – is quite literally in their hands

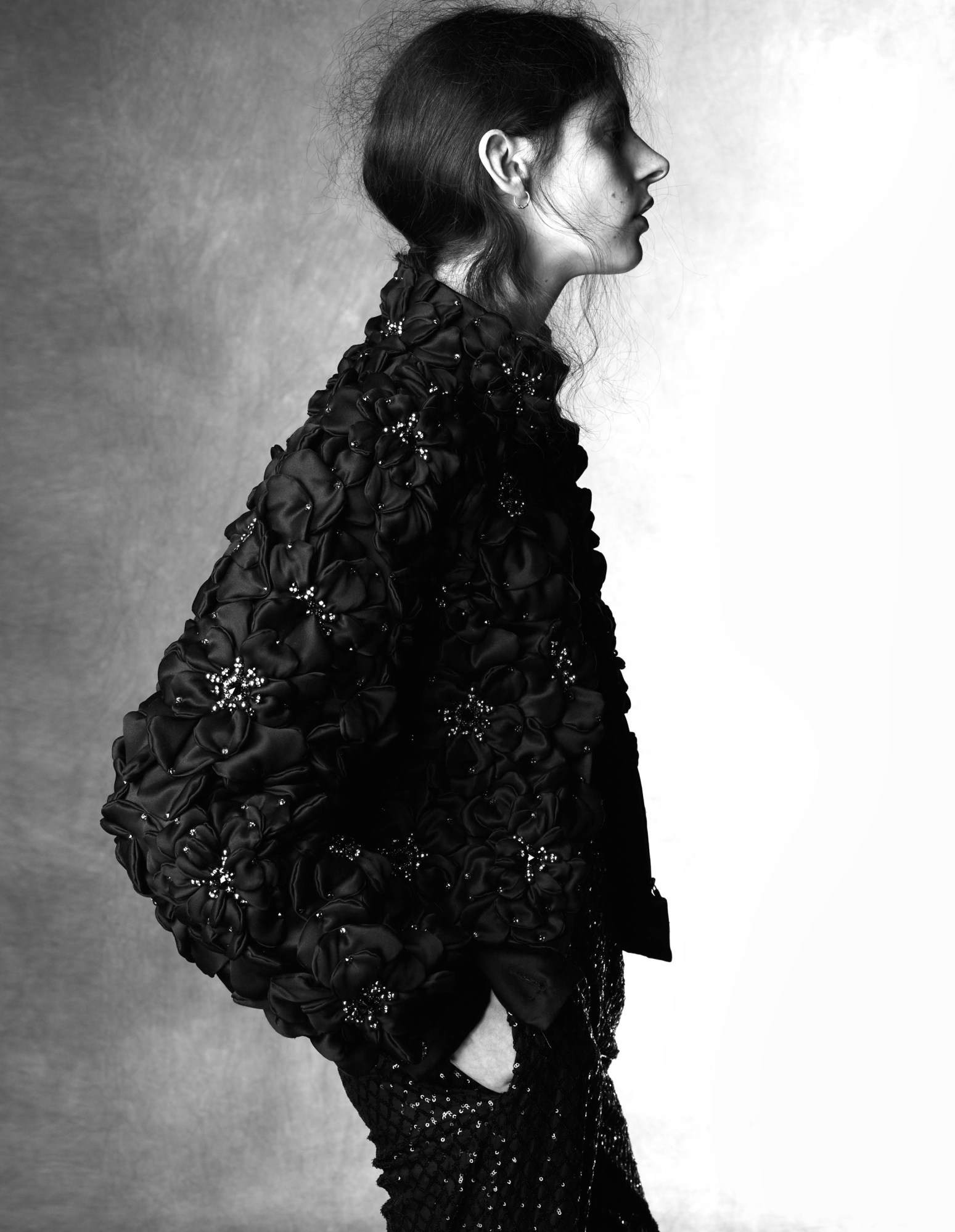

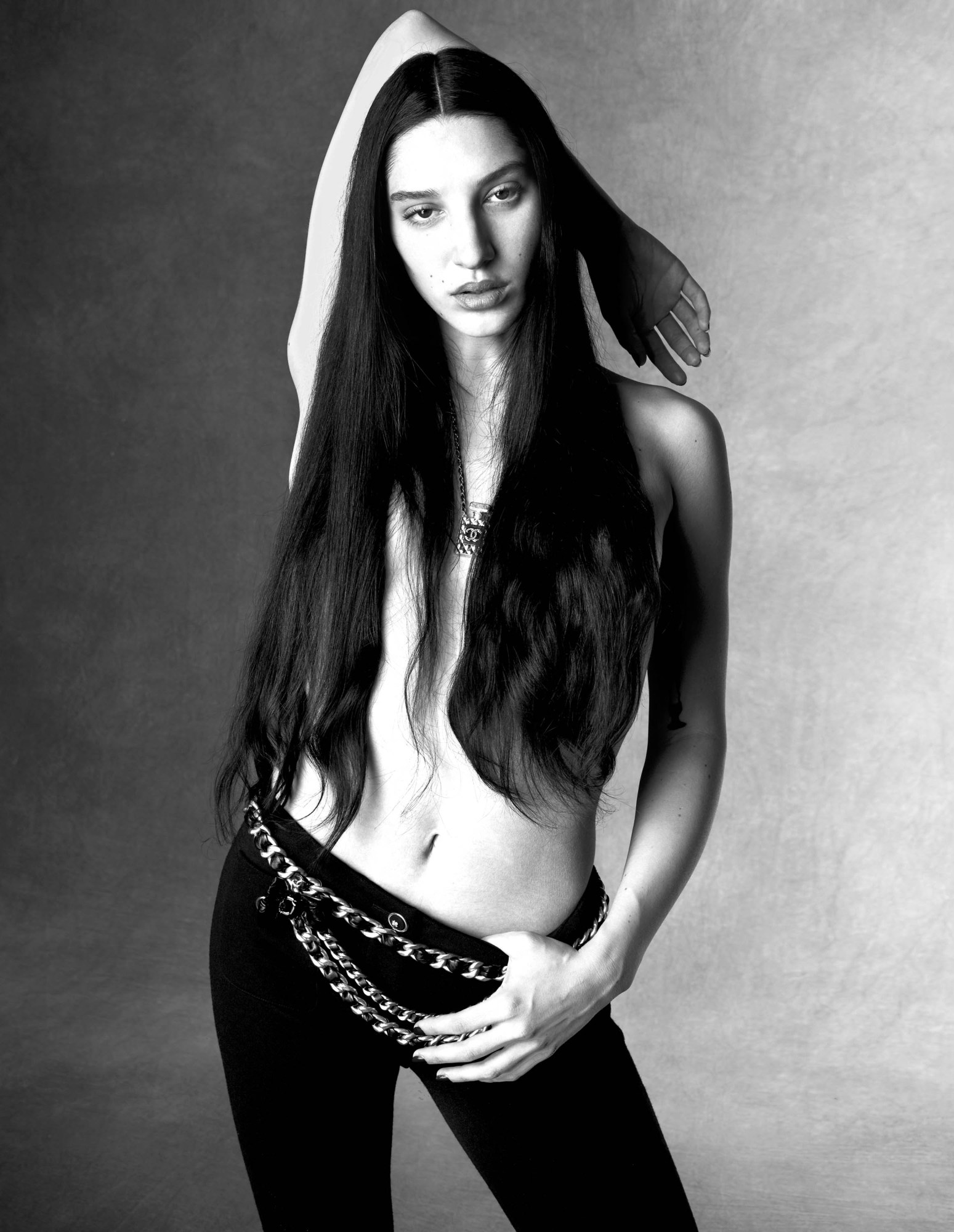

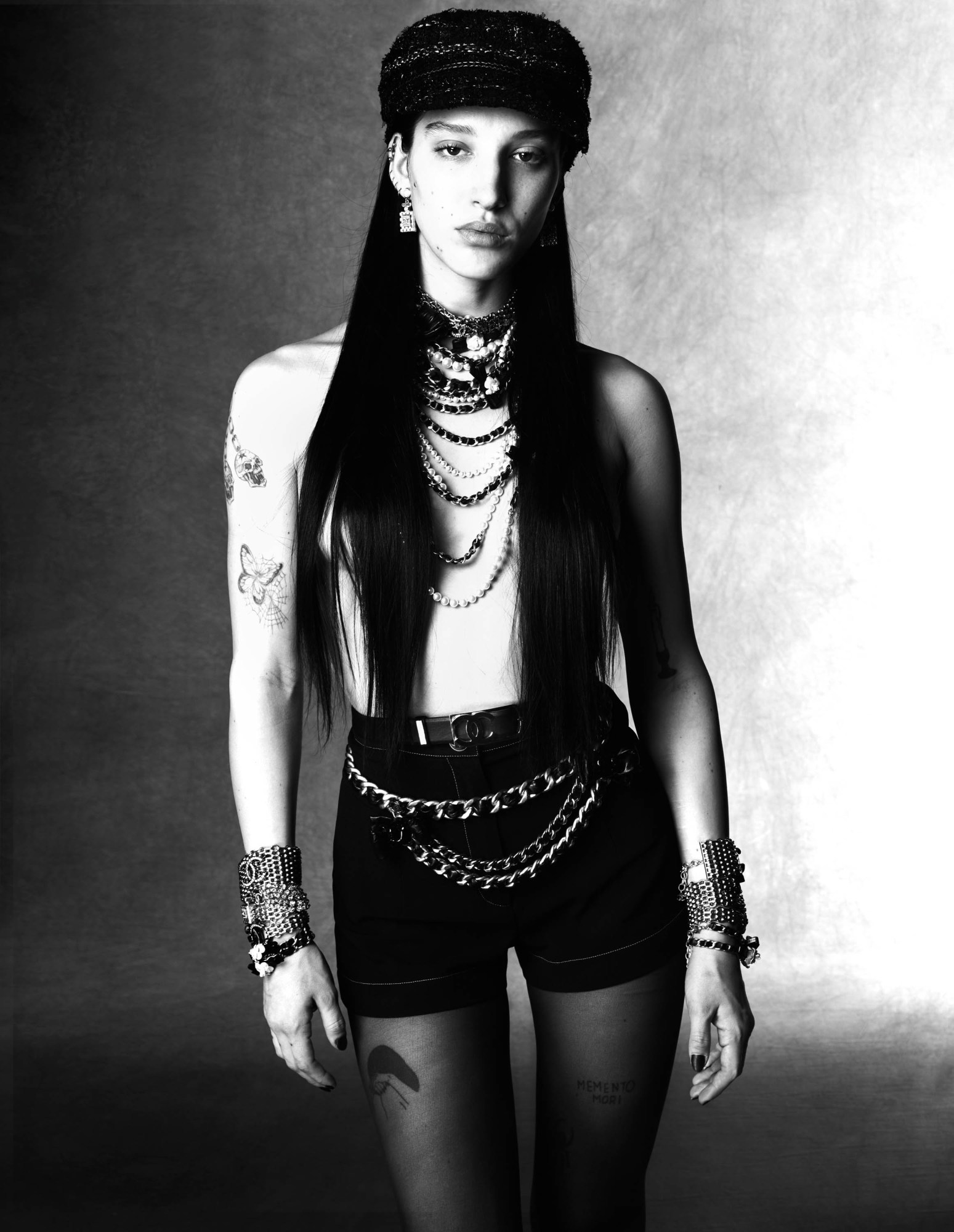

Credits

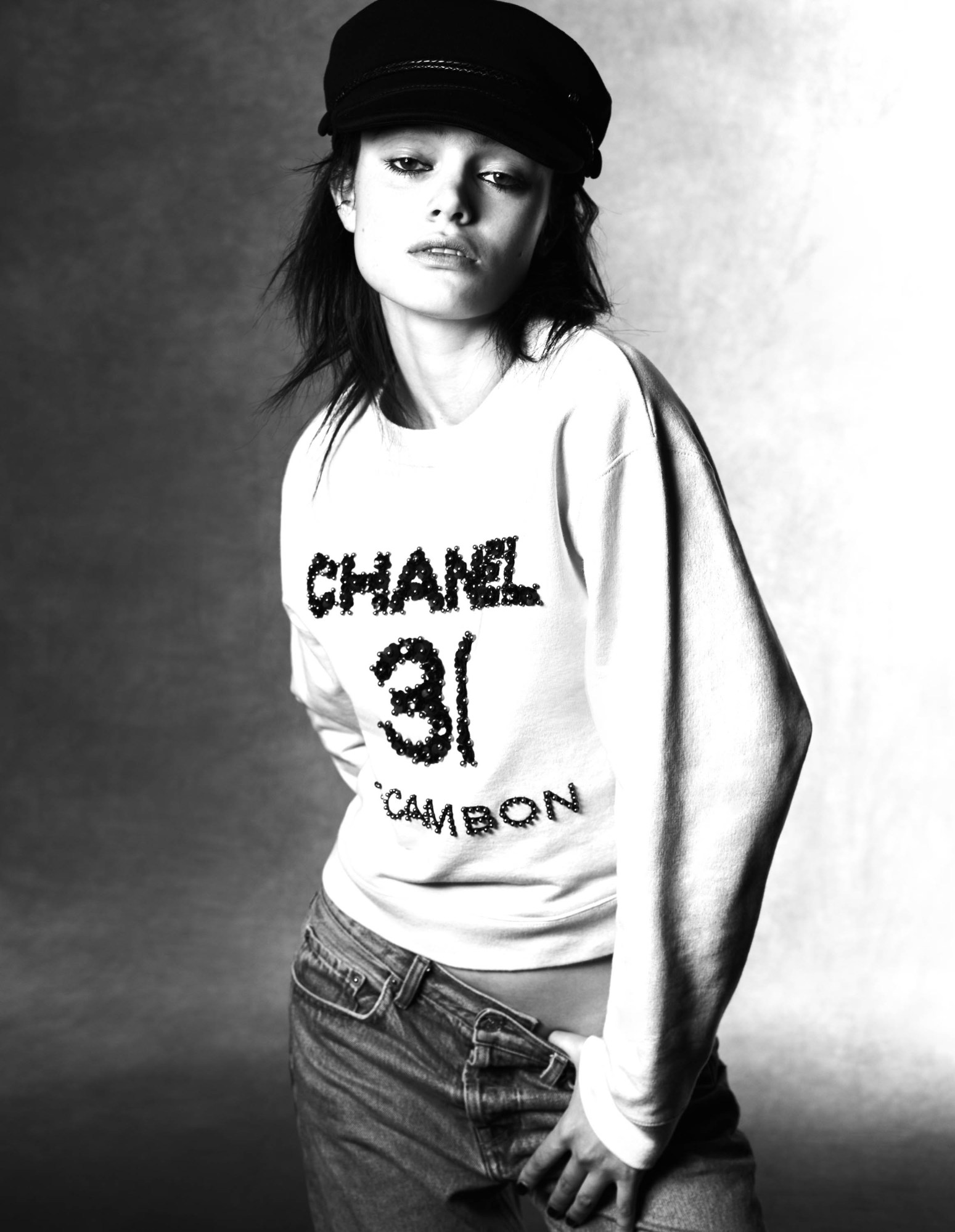

Photography Julien Martinez Leclerc

Styling Alastair McKimm

Hair James Pecis at Bryant Artists using Oribe.

Make-up Mark Carrasquillo at Streeters.

Nail technician Honey at Exposure NY using Chanel Le Vernis.

Set design Julia Wagner at CLM.

Photography assistance Kit Leuzarder and Karie Eng.

Styling assistance Madison Matusich and Zina Gladiadis.

Hair assistance Anton Alexander and Kyia Jones.

Make-up assistance Mikaila Hutchens.

Set design assistance Marcs Goldberg and Dylan Bailey.

Production Lolly Would.

Casting director Samuel Ellis Scheinman for DMCASTING.

Models Cyrielle Lalande and Simona Kust at Ford. Lola Nicon at Rebel. Oceana at Models1.

All clothing and accessories CHANEL Paris – 31 rue Cambon 2019/20 Métiers d’Art collection.

Lede image Briefs and tights stylist’s studio.