Ah, the Chanel suit, fashion’s oldest heirloom, synonymous with Parisian chic, femininity and classiness. From Jackie Kennedy’s licensed replica worn on the day of her husband’s demise to Barbie and Paris Hilton’s finest looks, that boxy, tweed bouclé two-piece has had pop culture in a chokehold from the mid-century onwards. All the while, it’s revolutionised women’s fashion, birthing one of the first sartorially focused conversations around gender and class.

Indeed, we all remember Marge’s Chanel suit from the aptly titled Simpsons episode, ‘Scenes from the Class Struggle in Springfield.’ After landing a baby-pink two-piece – gold buttons, black piping and all – at a life-changing markdown, Marge finds herself climbing the social ladder among country club WASPs. At first, she makes a grand impression thanks to the lucky find, but after recycling the fit a few too many times, Marge is revealed as a lower-middle-class phoney. It’s telling that Coco Chanel’s design, first conceived in 1925, was the garment used to tell this story. Without such a rich history, both as a marker of female emancipation and status, it wouldn’t be the icon it is today.

While it’s loaded with such discourse, it’s also eternally stylish – hence why it’s remained the outfit of choice for ladies that lunch, le nouveau-riche and art school girlies graduating in their grandmother’s hand-me-down alike. In some ways, it’s as democratic as it is elitist. From one perspective, it represents the haughty prissiness expected of high-society ladies, while from another, it’s the antithesis to old-world couture, ditching corseted uppers and heavy bouffants for something boxy and comfortable. To get to the bottom of why Gabrielle Chanel’s design remains relevant all these years on, we unpick its history and more recent iterations, charting its path from an incendiary riposte to Dior and Saint Laurent to an endlessly viable template to comment on taste, social standing or womanhood.

New Money

Believe it or not, Coco was common as muck, at least as a youngster. Hers is a story of rags to riches. “Coming from a very disadvantaged childhood and making her way in early 20th century society, Chanel was acutely aware of the issues of class,” explains Oriole Cullen, a senior curator who worked on the Victoria & Albert’s current exhibition, Gabrielle Chanel: Fashion Manifesto. “She obfuscated her background in order to be accepted into fashionable society and used her own image to represent her brand.” In other words, she adopted the very lifestyle her label purveyed, dressing up to get on, despite the prevailing attitude that designers, seen then as tradespeople, were unwelcome in society.

However, her suit designs didn’t immediately capture the upper class. When first released, not only was the fit the antithesis to fin de siècle couture, but the materials she utilised were anything but opulent. Yep, tweed, then an export of the hardy Scottish mills, was one of her chosen materials. “It was me, in fact, who taught the Scots to make lighter tweeds,” Coco once said. As well as upping the saturation of that old fabric, she also pushed the mills to explore different textures, softening the once rugged classic.

A New Woman

One of the immediate pushbacks Chanel’s suit faced lay in its masculine connotations. Granted, today, it’s the zenith of femininity, but back then, it was proto-blokecore. Offering easy movement thanks to a roomy construction – not to mention an unfussy, collarless design – it smacked of menswear. In those days, men were the workers, and only they would need such loose silhouettes. Aristocratic women weren’t expected to graft, let alone wear clothing inspired by men’s shooting and outdoor garments. However, it was this style, often worn by her then-boyfriend, the Duke of Westminster, that gave rise to her ‘garçonne’ cardigan suits. Plus, as well as tweed, her suiting was also designed using jersey material, formerly the reserve of men’s undies. That’s jockstraps, back then.

“It can be hard to appreciate Chanel’s impact because the construct of ‘femininity’ and evolution of linear fashion trends has become so much more fluid in the 21st century,” says Amy de la Haye, author of Chanel: Couture & Industry (2011). Having first pushed the jersey pieces in the 20s before stopping business during the Second World War, Chanel aired her suit again in 1954, focusing on its tweed iteration. “It was again radical by comparison. Chanel was reacting to the anachronism of Christian Dior’s unashamedly romantic 1947 corseted and extremely full-skirted ‘New Look’.”

Sharing is Caring

While the Chanel suit embodied bourgeois dress for the 20th century’s latter half, it was also a wider symbol of femininity across the class divide. Coco was unphased by the threat of copycats, and instead, during the 50s, embraced licensing, allowing her designs to be produced in US department stores, like Saks Fifth Avenue or even middle-of-the-road UK retailers, such as Marks & Spencer and Wallis.

As well as this, “The simple cut of the suit was relatively easy to replicate at home and so pivoted the design into the hands of dressmakers, giving them access to high-quality fashionable design,” notes Dr. Sian Weston, a fashion researcher at Chelsea College of Arts. “This caused a change in demographic as Chanel was aimed at socially elite women, and this particular design gave women from lower social classes access to the brand.” Quel horreur! At least, for the likes of other couturières working at that time, this would be the standard reaction, but Coco was unphased. As such, her suit became not just a symbol of status among the monied parisiennes, but also a template meted out to a democratic mix of women. Heck, in today’s age, when IP is kept under lock and key and industry watchdogs are ready to jump at the slightest moodboard crossover, such a laissez-faire approach would bring Corporate out in hives.

Ready Made

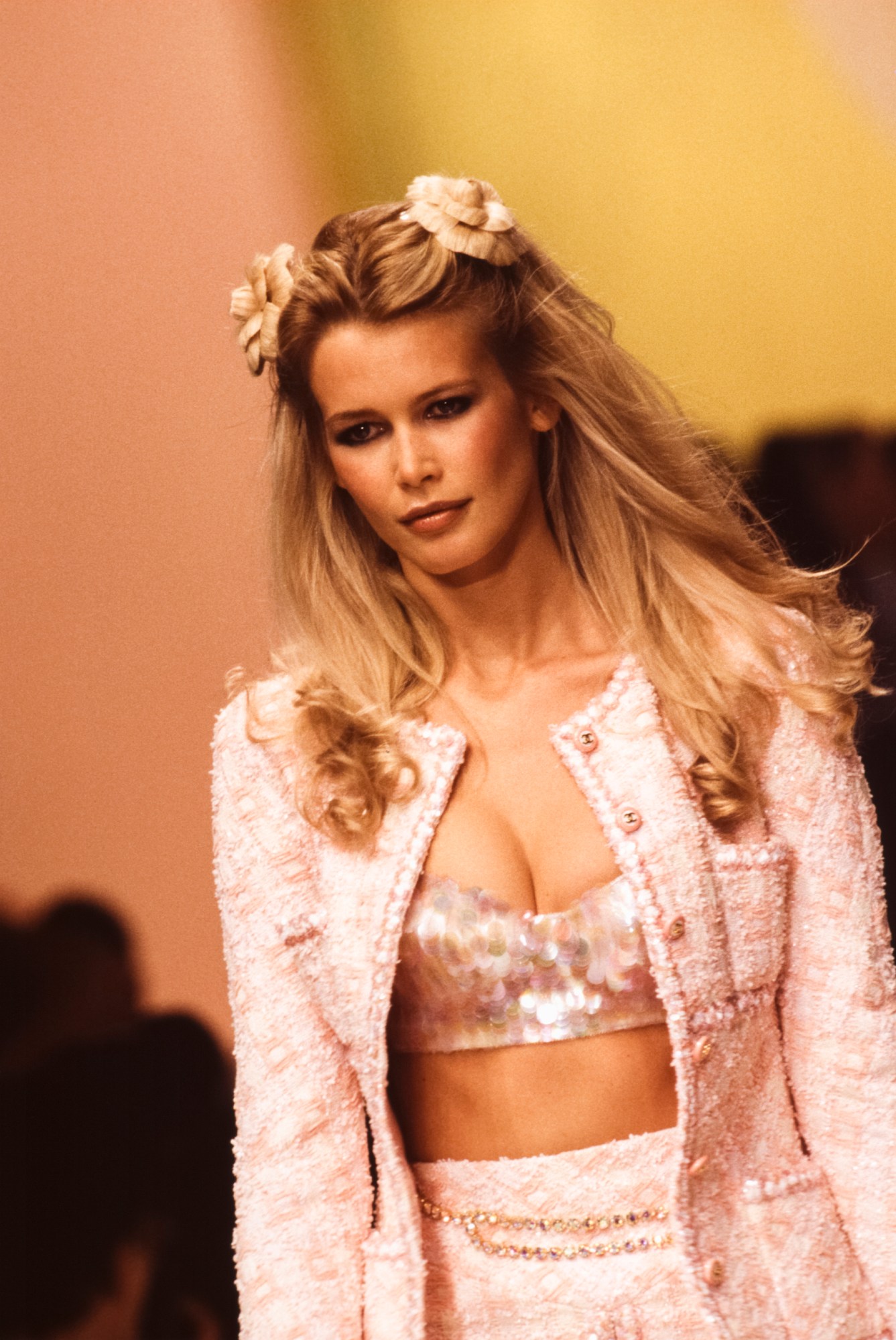

With time, the suit’s template became a source of subversion or reinvention. In this arena, Karl Lagerfeld, Coco’s successor, who helmed the brand from 1983 until his death in 2019, set the pace, reimagining what had been a cemented classic with a playful irreverence. Chanel suits evolved into red-piped leather two-pieces for SS87, denim tuxedos for AW91, and lapelless menswear blazers for AW08 – talk about full circle. In many ways, this gave carte blanche to the tongue-in-cheek labels birthed in the 80s. After all, if Karl was willing to render such a hallowed item into gaudy tartans or even hotpants, then clearly, this was just the tip of the iceberg.

And so it was that Franco Moschino’s AW89 collection would directly jibe on the Chanel suit, keeping the same modest and roomy cut, collarless neck and skirt, but adorning it with golden spoons in lieu of the original golden buttons. From there, came a whole spectrum of weird and wacky apes, spanning the cowbell-decked bouclé tweeds of SS91 to the pom-pommed, polka-dot and plastic-ribboned designs of AW94. “I know the history, which is the reason I can joke,” Franco told the New York Times in 1986. In the end, this exercise in kitsching the ultimate status symbol – one of prissy femininity and the chi-chi lifestyle purveyed by Karl and Coco’s girls – added yet another semiotic layer to the legendary twin-set.

Naturally, the king of camp, Jeremy Scott, found plenty of other ways to riff on the look of untouchable femininity. His runway debut for AW14 was perhaps the brashest assault, colouring Chanel’s suit with a McDonald’s palette, or simply trimming its pockets and piping its hems with a Golden Arches M-print. What better way to give the bourgeois femme a taste of proletariat life than dressing her up in the uniform of zero-hour contracts and service with a smile through gritted teeth? After that, Jeremy ran with it, serving Barbiecore cardi-skirt sets for SS15 and even hi-vis workwear editions for SS16. Of course, it’s easy to see why these jibes work so well. Just watch the latest Barbie film, whose costumes were designed as part of an official Chanel collaboration. The Chanel suit and Barbie’s perfected, propertied femininity go together like Barbie and Ken.