Charles H. Traub is not a beach person: he doesn’t like slugging all the gear, the umbrellas, beach towels and picnics; he thinks the sand gets everywhere. He’s also rather restless and doesn’t enjoy sitting still. The photographer does, however, find beaches fascinating places for the way they attract a diverse cross-section of the population, who gather together in close proximity. Beaches are pretty democratic spaces, he says, where class doesn’t really matter. No one cares who you are, what you do for a living or what your hobbies are: “On the beach, the mask comes off. It is a place where people basically let it all hang out, let their inhibitions go.”

From the late 70s into the early 2000s, Charles documented beachgoers around the world from Rio to Chicago, Naples to New York City. The front of his new book, Remembrance of Summers Past, features a birds eye shot of Blackpool beach, where sun-frazzled Brits sprawl at varying angles between striped windbreakers and blue and white deckchairs. He was drawn, he says, “to this almost sculptural gesture of the entanglement of people”.

In the book there’s a lot of pictures where hands or bodies are touching, Charles says, because “there’s always a lot of love on the beach, and there’s very little violence”. It’s a place to cool off, calm down and forget the stresses of the real world. At New York’s Orchard Beach, lovingly called the Bronx Riviera, a couple embrace: her pink nail varnish compliments his leopard print bottoms. In others, friends share towels with their limbs touching; children scramble to apply pebbles to their parents’ backs and lovers massage suncream into one another’s backs. People are covered in powder white sand and sweat, glistening in the heat: their bodies positioned to face the sun.

Jean-Claude Lemagny, a photography historian and former curator of France’s Bibliothèque Nationale in the 70s, once told Charles: “You know, you’re a Baroque photographer”. He was looking at Charles’ Beach series — a collection of black and white images taken along the concrete boardwalks of Chicago’s coastline, where he lived for nine years — which was published in 1977, and decided the way the bodies were entwined and stretched out drew similarities to the style of art that emerged in Europe in the 17th century, known for its sensuous richness, drama, dynamism, movement, tension and emotion.

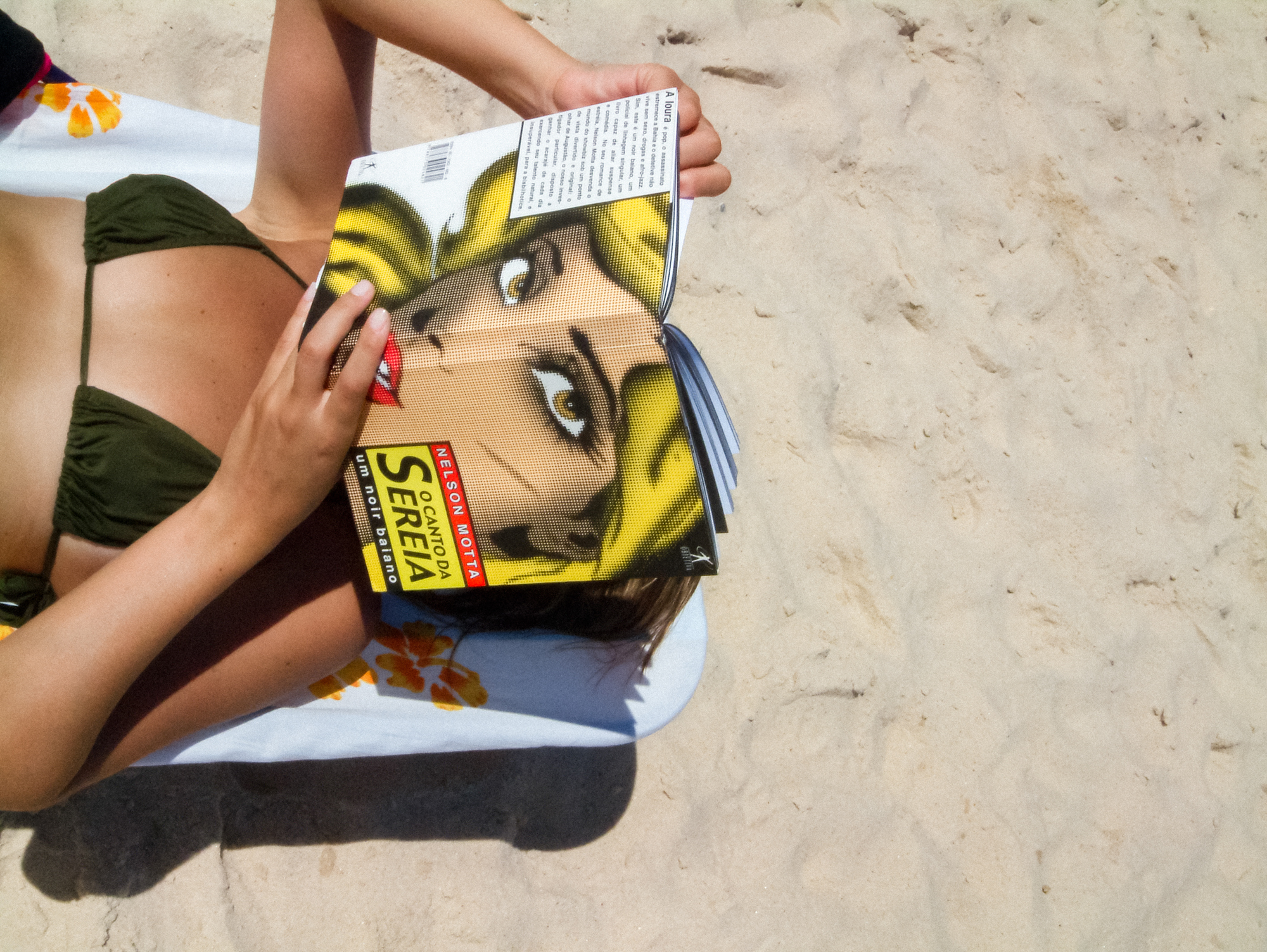

Although faces are shaded from the sun by books, towels or hats, there’s personality in the photographer’s images. Men peacock and elderly women survey the naked bodies in front of them, while oiled up women bake in the heat. Throughout the book, there are moments of humour: a sun-drenched couple lying on concrete wear a tiny pair of tanning goggles, and a burnt nude couple are surrounded by a clothed mass on Jacob Riis Beach.

Charles says that he always wanted there to be a yin and a yang to his images — something happening, in which there’s also some counterpoint that isn’t exactly what it appears to be. He wants the question to be raised: why are they doing that? Or simply, for the viewer to feel comic relief. “I’m trying to make things connect throughout the image with a gesture and a counter gesture or a colour and a counter colour,” he says. “It gives the picture energy.”

Sometimes the shadow of the photographer is present in the image, which Charles was careful to include. It gives “honesty to the picture,” he says. “I’m there. I’m part of the picture. I’m part of the reason that picture is being made, [and] I am part of the reaction that people may have. As I’m looking on to them, they’re looking at me. There’s a shared gaze.” It’s a different position to the one legendary American photographer John Szarkowski takes, Charles explains. In his book The Photographer’s Eye, which has massively informed modern photography studies, John suggested that the photographer should try to be omnipotent, but Charles disagrees. “I don’t think that’s right,” he says. “I think our presence is largely what the picture is about.”

According to Charles, the photographer’s presence changes the scene. He rarely snuck up on his subjects on the beach, instead choosing for them to be active participants in his photographs. He found that, on the whole, “people want to be seen and people want to look,” he says, and “[the beach] is a place where everybody looks”. Charles references the work of the sociologist Erving Goffman and his book, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, which argues that social interactions are like theatrical performances, where people are like actors on a stage before an audience, which ultimately influences how the actor behaves. “The gestures they make are part of their public display and it’s not a totally unconscious issue,” Charles says. “They want to be recognised for that act.”

There is one picture taken in Jamaica that has always felt quite loaded for Charles. In it, a white woman walks along the beach topless surrounded by a mass of Black men. She seems to scream, he says, “I’m white, you can look at me but don’t touch”. For him, there’s always been something quite brazen about that image. Other times, it’s more performative, like a group of young boys who laugh at their friend lying on the beach naked from the waist down.

“I find the beach a place for all the gestures,” he says, “all the physical attributes of our humanism come out without much inhibition. I love working anywhere where people are in groups, and meeting people wherever I am. I’m never without a camera.” He calls himself a “wandering real world witness photographer”, and hates labels like street photographer or documentary photographer. For Charles, there’s something active about his work, it’s conceptual and carefully chosen: the highly saturated images are full of push and pull, drama and creativity, moments of sweltering joy and peace.

‘Remembrance of Summers Past’ is available now

Credits

All photography courtesy Charles H. Traub