On Wednesday 28 July 1993, police and immigration officers forced their way into a flat in North London and dragged a woman out of the bed she shared with her 5-year-old son. They sat on top of her, binding her arms and legs, and strapping 13 feet of surgical tape around her face. Unable to breathe, she collapsed, suffering brain damage and cardiac arrest, dying four days later in the Whittington Hospital. No charges have ever been brought against the officers who killed her while trying to force her deportation.

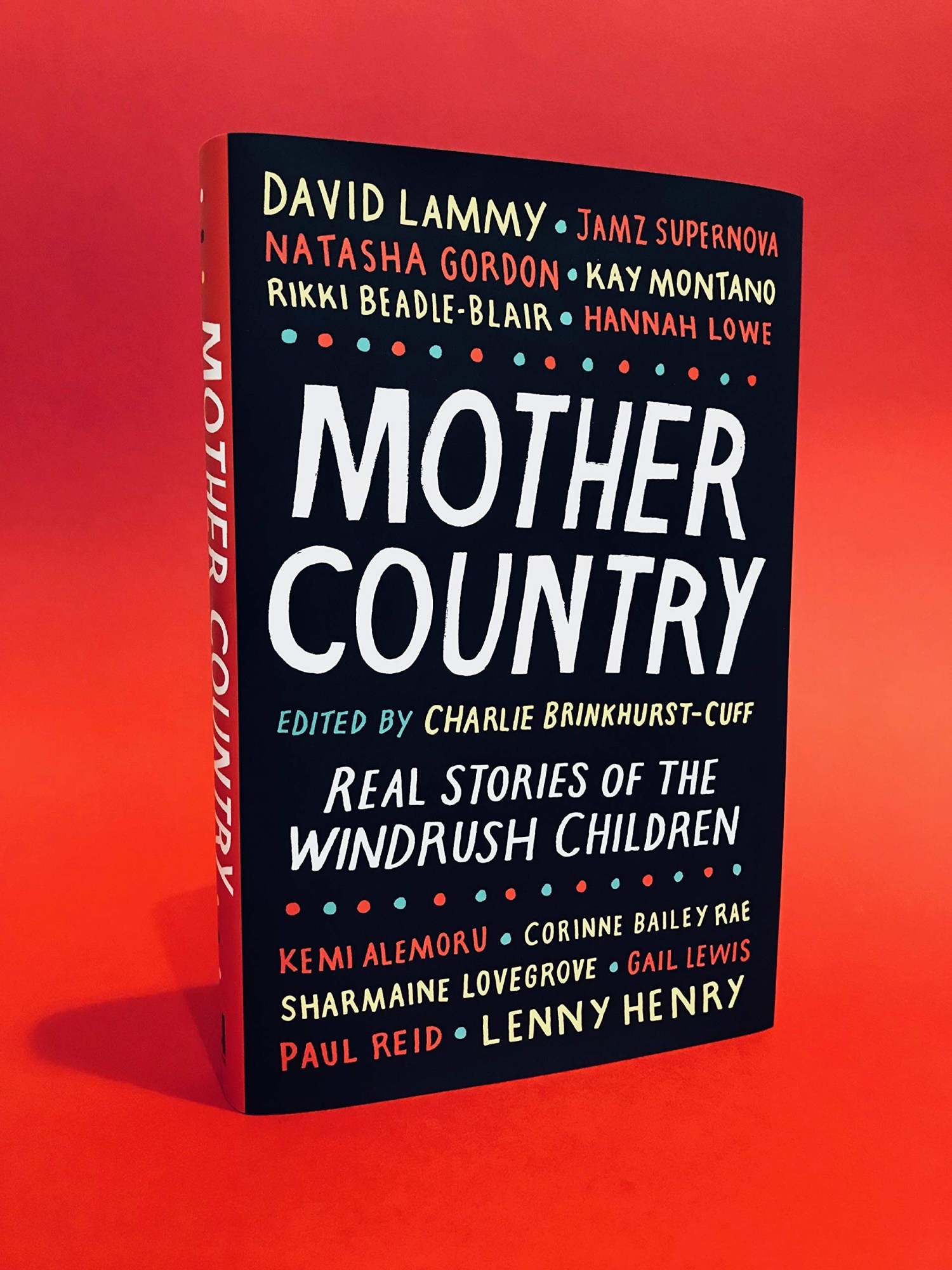

The woman was Joy Gardner, a Jamaican mature student who had been living in England for six years, and her heartbreaking story is retold by her brave mum, Myrna Simpson, in Mother Country, the new book by Charlie Brinkhurst-Cuff.

Mother Country is a selection of real stories from the children of the so-called Windrush generation, stories from Caribbean men women and children who came to their ‘Mother Country’, Britain, on British passports, to build a new life. Broadly speaking the Windrush generation refers to the groups of people who immigrated on the Windrush and other ships, after WWII, legally and after being invited, to Britain, from the Caribbean, which at the time was still a part of Britain (a British colony). This year, the Windrush generation made front page news with stories of British Caribbeans were deported more than 50 years after their initial arrival in England – following a Hostile Environment Policy propagated by the Tories, which, coupled with the confusion over some British Caribbean’s nationalities when their countries were granted independence from Britain, led to forced deportation. With the scandal dominating the headlines though, it’s easy to forget the real people and individual stories which make up the crisis. With Mother Country, Charlie is making sure that never happens.

Not all of the Windrush stories in Mother Country are as heart wrenchingly sad as Myrna Simpson’s and Joy Gardner’s. While for many of the 22 real-life stories included in the book, racism and violence was sadly unavoidable, there’s joy in these pages too. Singer Corinne Bailey Rae talks about finding her place as a British Caribbean woman through her music. Howard Gardner, whose father travelled over on the HMT Empire Windrush, speaks of his idyllic childhood growing up mixed race in Yorkshire. Comedian Lenny Henry explores the spirit of adventure which fuelled the diaspora, and Labour MP David Lammy speaks with pride on celebrating the impact of the Windrush generation on the 70th anniversary of the ship’s arrival in Britain. “When no one else in Britain would, the Windrush generation did the low-grade and poorly paid jobs that kept Britain running,” he writes.

For those familiar with the Windrush scandal, the argument that British Caribbeans propped up public services, like nursing homes, TfL and the NHS, for many years (which, of course they did) is a well known one. But that argument also plays into the problematic discourse of the ‘good immigrant’, a stereotype that Charlie was determined to dismantle with Mother Country. “I hate the narrative of the good immigrant,” she tells i-D. “Of course it was used to the Caribbean community’s advantage in tackling the Windrush scandal because it made people pay attention. We live in a patriotic society, so while I wish it wasn’t important to hear things like ‘oh they came over here and fought in the war’, unfortunately that did matter.”

“I just wanted to disrupt so many of those narratives because so many of them are just so inaccurate, they don’t actually reflect the reality of our lives. A lot of the people I spoke to were just so annoyed about the way in which we are portrayed, like, for example the idea that all Caribbean men are lotharios. Yes, there are and have been issues because of the intergenerational trauma that we’ve been through that reflects itself in our family structures, but there are also so many people, like in my family, who are responsible, loving caring men who wouldn’t dream of having multiple partners.”

It’s family that’s right at the heart of Mother Country. In every story there are reverent descriptions of untouched, typically Carribean front rooms, where the children weren’t allowed to play, of rowdy shebeens and loving matriarchs. But, in a culture where family is so important, it’s impossible to not also explore the familial trauma that comes with generations of racism and separation — many of the stories in the book allude to the pain and complication that comes with uprooting part of your family to another country, and inevitably leaving others behind while you lay the foundations of a new life, thousands of miles away. “When I started writing, I knew I wanted to touch upon themes that are often overlooked in the Windrush and British Caribbean conversation,” Charlie says. “I wanted to explore intergenerational trauma, racism, colourism and make sure there was an LGBT dialogue and space for female voices.

“I learned so much in putting together the book about what it is to be a Caribbean,” she continues. “I don’t go too much into my own background in the book and that’s partially because, even though I’m telling everyone else to speak to their grandparents and get their stories, it isn’t always the easiest thing to do. There’s a lot of hurt in my family and a lot of that is tied to the trauma of Windrush, separation and family deaths. But it’s still something that I need to work on as well, like going to see my nanny more often! This project has definitely given me the confidence to do that in future.”

For a book that’s so tied to the historical, and focused ostensibly on one event (the arrival of the Windrush) Mother Country uses the events of the past to look towards the future. “Windrush isn’t the only part of our story,” Charlie explains. It’s a placeholder to look forwards and look backwards. It represents only one facet of Caribbean British migration, but we have to look at the wider history which is British colonialism. Until we have work from people like David Olusoga [who wrote Black and British: A Forgotten History] being taught in school and until people realise that the Caribbean was a colony full of people who were British, the issue won’t be fully understood. There were British colonies all around the world with awful histories of slavery and indenture, and we’re still scratching the surface of those stories.”

For the Windrush generation, the stories seem to at last be improving, albeit it unbearably slowly, as Theresa May was forced to apologise for deporting British Caribbeans “in error”. But with Brexit looming, and anti-immigration sentiment on the rise, we need to be more vigilant than ever that the naked, institutional racism and violence that Windrush immigrants faced on their arrival in Britain doesn’t repeat itself.

“I didn’t put the book into a Brexit context until recently,” Charlie admits. “I was on a panel and there was a Polish woman speaking on her worries about being ‘sent back’ given that she’d built her life here in the UK. We have to remember that, ultimately, the reason Brexit happened is because the majority of people who voted for it as their main concern was immigration. And that doesn’t necessarily reflect upon European immigrants, who aren’t always the most visible immigrants. In reality, it’s black and brown people who are being seen as most unwelcome. Brexit is an awful thing for immigrant communities as a whole and it’s very telling that it also came from communities which are predominantly white and have low rates of immigration.

“It’s the fear of the unknown, places and communities who are not used to seeing other faces, who are the most worried.” With Mother Country though, Charlie is making sure that these faces continue to be seen.

‘Mother Country’ is available to buy now. You can find out more about the book on Charlie’s website .