In October of last year, we invited a series of young writers to reflect on what Britishness means to them for The Superstar Issue of i-D. From the nostalgia of home, to fears over rising rents, to the sense of displacement from the place we thought we once knew, our identity has never been more complex. So what does being British mean for a country facing its biggest shift in decades? And does it still matter? Read the full series here.

My story of Britishness follows that of so many people whose grandparents died before they were born, but it is complicated by the movement of the oceans and the paths of migration enforced and later encouraged by white Europeans upon black Africans. Can you have a British identity if you don’t really know where half of your family is from, apart from the fact that it was the British who stole them from there?

My grandad, who my mum knew as George Cuff, but – thanks to a rogue discovery of a passport – may have really been called Fernando Benito, a name perhaps more reflective of his Cuban heritage, moved to the UK in the 50s as part of the Windrush generation. He was a short man with a round face, squished button nose and a burnished brown skin tone, with a small, tight smile. He looked harmless and sweet but not particularly handsome. He didn’t look like he could speak Spanish but if his name really was Fernando Benito and he really was born in Cuba then surely he could have?

I’ll never know if he was an English patriot, one of the men who would’ve fought in the war for the British if he had been old enough, caught up in the fervour of the Caribbean Regiment and the enthusiasm to defend “King and Empire”. Closer to my heart, I can paw at the idea that he had a sweet tooth like me because I know that he always kept treats tucked away in his pockets for his children. I imagine sticky-greaseproof wrapped toffees and boiled stained-glass coloured cylinders. I don’t like asking my mum and aunty about him because the tears that still spring to their eyes, decades after his death, are ultimately more painful to me than not knowing his story.

I put a lot more weight on the heritage within me that everyone notices. While I’m interested in the identity of my family on my dad’s side – Kentish farmers and labourers to the last spindly branch of the family tree – it’s my blackness that has always been stamped on my face in the puff of my lips, the round of my nose, the light, but not quite white skin tone. No one really cares to know where my white family is from; but the interest in my black family is always tinged with the exoticism of difference, and when people see that difference in you, I don’t think it can be helped to find it within yourself.

The first time I went to Jamaica, in 2016, it didn’t feel like a homecoming, and I now know that even if I ever do work out the true journey of my grandfather across the seas – whether he is from Jamaica or Cuba or neither – it still won’t make me feel any more Caribbean. My Nanny is firmly Jamaican; born in the parish of St Anns, and like so many others of the Windrush generation is likely to have had quite a quintessentially British upbringing. It’s not a falsehood that they were taught to love the queen, read Enid Blyton and thought that upon coming to the United Kingdom they would be welcomed with open arms.

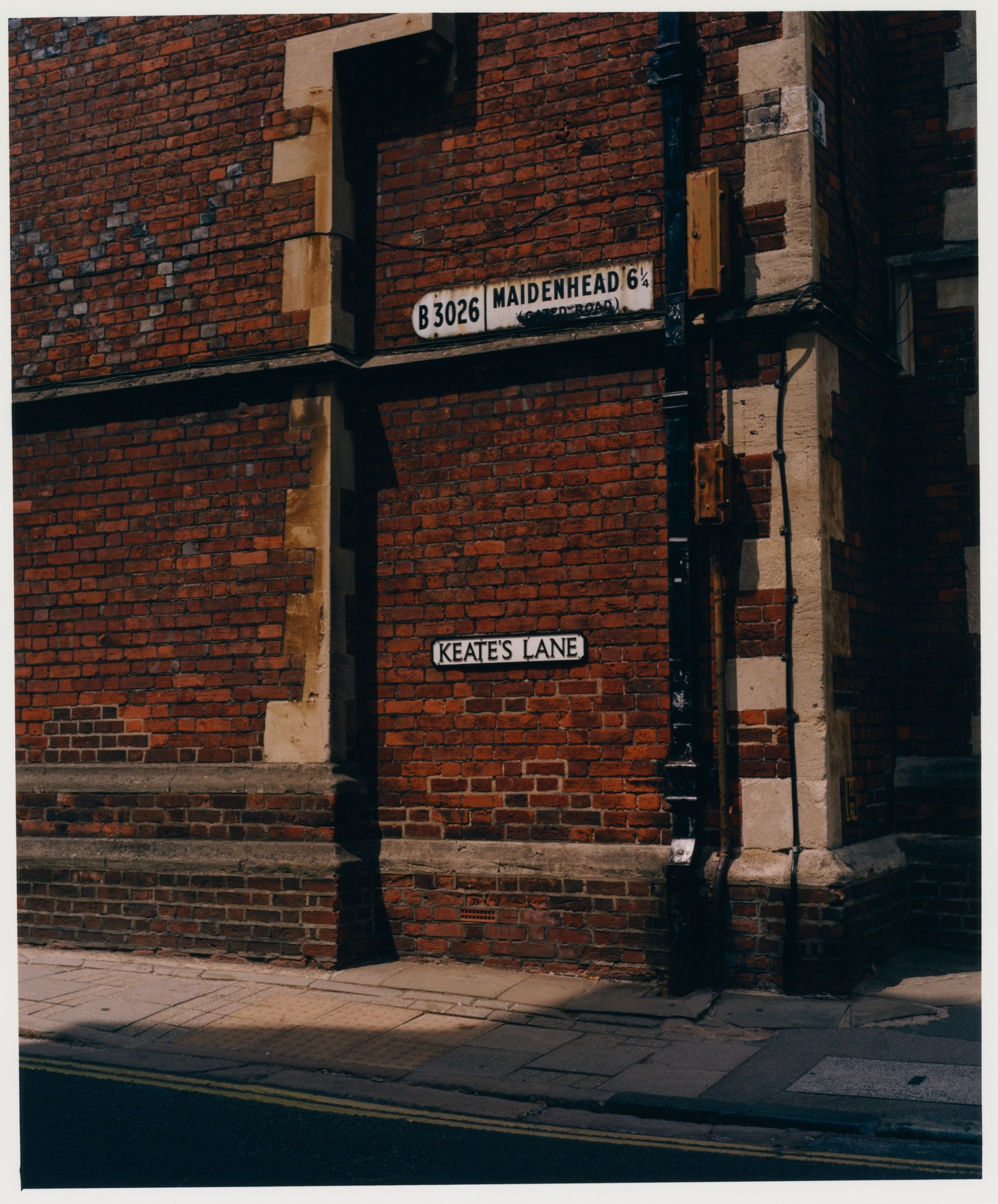

Just as Windrush migrants struggled to find home inna Englan, Jamaica, with its beautiful patois, as foreign as any other new language to me, Otaheite apples which are soft and sweet and not at all crunchy, rolling hills and crocodile eyes in the Black River, and my relatives, who were so soft and kind and welcoming, was not home to me either. I had never felt more British than I did in the place that I had always dreamed would make me feel at peace with my identity, where I might fit in.

So, as I recently wrote in the introduction to my book Mother Country, on the children of the Windrush generation, “having visited the country twice now, I know who and what I am, which, it turns out, is a mess of contradictions.

Credits

Photography Sam Rock