I grew up with the presumption of early death. I was eight years old in 1981, the year of the first reported AIDS deaths. It was around the same age I first knew I was gay. To be a queer kid then was to not just survive entrenched societal homophobia but to face the prospect of dying young.

In 1996, anti-retroviral treatments were introduced that made it possible to live a full life with an HIV+ diagnosis. I was 23. By then, the basis of my entire worldview had been formed, set against years of death and death and death. The AIDS crisis affected everything: I kept myself hidden to keep myself alive. I knew I didn’t have the emotional intelligence to ask a guy to wear a condom. I know this because, when I did start sleeping with men in 1999, I often put myself in danger. In the moment, just as a guy was about to fuck me, I couldn’t say what I needed to say.

I was already a journalist. But I have often found it hard to express what I wanted to say about the AIDS crisis. Journalism—for newspapers especially—needs facts. And yet, there are no facts in a vacuum. So many died, and with them died what they could have done, how they could have lived.

It was in fashion that it first struck me. In 2005, I took a job that focused on menswear. At the time, people would say things like, “Menswear in London is dead.” If a student studied menswear, it was assumed they’d just go and get a job in Milan or Paris. Setting up their own label was such a remote possibility—there was no support, no infrastructure, no encouragement. London Fashion Week was only for womenswear.

Then, Lulu Kennedy of Fashion East got to work. She started an off-schedule menswear showcase, and suddenly, things started to happen: Kim Jones, Martine Rose, JW Anderson, Craig Green, Nasir Mazhar. People spoke of it like this was a new menswear movement, but to me, it felt like bringing back what always should have been.

As a kid, I self-educated through i-D and The Face. The radical fashion of the early-to-mid ’80s was a mingling of men’s and women’s design. The pinnacle of this was BodyMap, an ’80s label which championed diversity, body-positivity, and gender enlightenment. After soaring for seasons, BodyMap collapsed from financial mismanagement, at a time of severe stock market crash. By then, the AIDS crisis was devastatingly established. No one from the next generation came to follow their lead.

Here is where we leave facts. We can never know the work that would have been done by those who died. It’s not just known names; it’s also those who died so young that they never even got the chance to make their name. Fashion is an ecosystem—as well as designers, we must consider stylists, and those who never got the chance to be a stylist. The same goes for hair and make-up artists, shop owners, buyers, customers.

It is as if there is a parallel universe where men’s fashion was able to evolve as it should have done—if the AIDS crisis had never happened, if no-one had died. But it’s so hard to express this parallel universe. And so, it gets ignored. I believe men’s fashion, and fashion in general, has still not accounted for those who died between 1981 and 1996. We are still living with the effects of the AIDS crisis. We have still not learned from what happened four decades ago. We have still not allowed radical creativity to regrow. Instead, fashion has become “luxury.” Fashion is not necessarily luxury. Luxury is banality. Wake up.

The loss is particularly stark in fashion. But I believe it also exists in other cultural spaces. Take art, for instance—it’s always struck me how the YBAs of the late ’80s (Damien Hirst, Tracey Emin, Sarah Lucas, etc.) were so predominantly straight. It’s so disrupting and destabilising to think about what could have—should have—been, rather than what we are left with. It’s also energising: What can we do now to make a change?

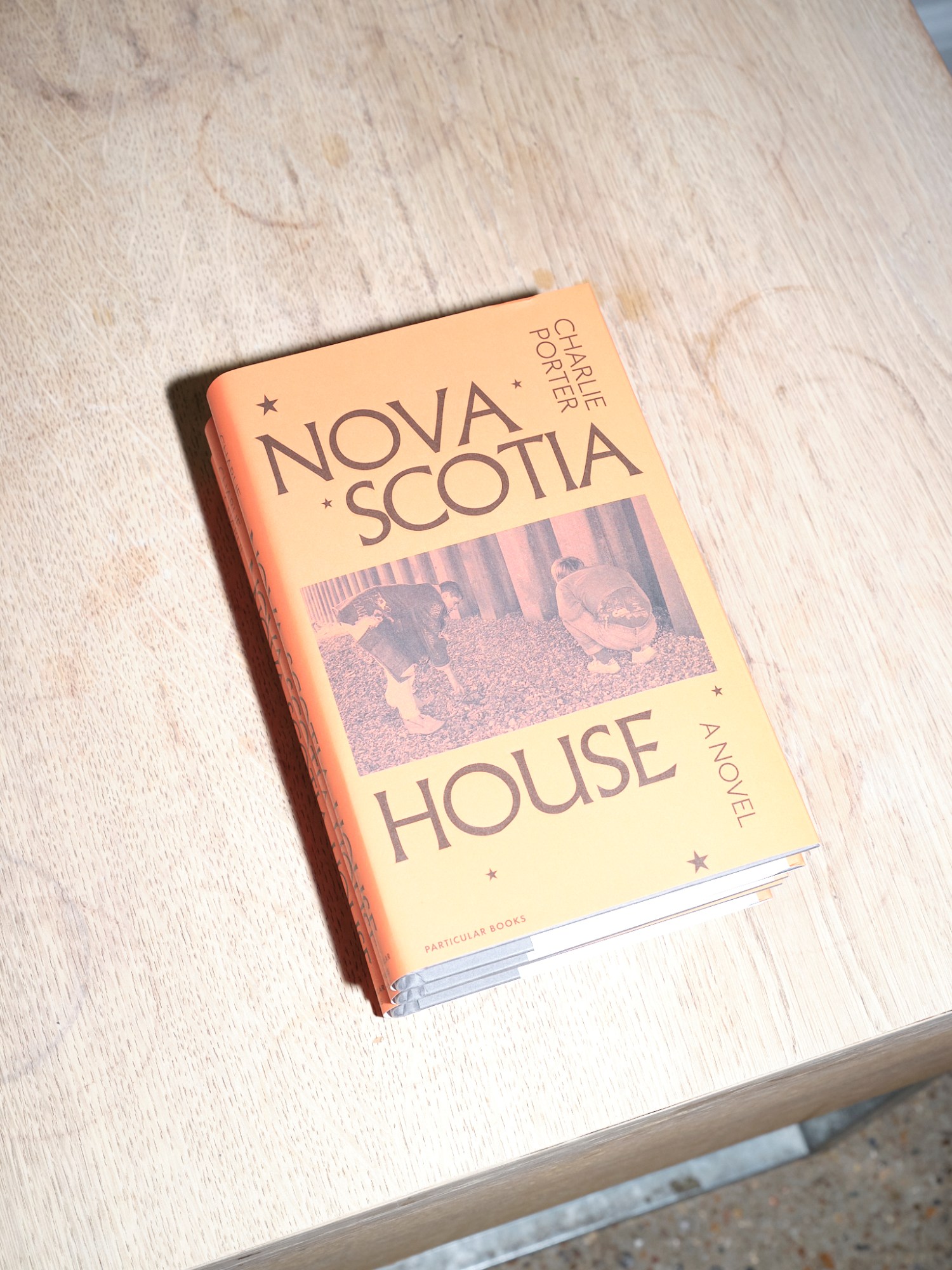

I’ve written two non-fiction books that rely on primary sources, What Artists Wear and Bring No Clothes. But to tell this story about the AIDS crisis and its enduring effects, there are no primary sources—only the parallel universe. And so to tell the story, I wrote fiction.

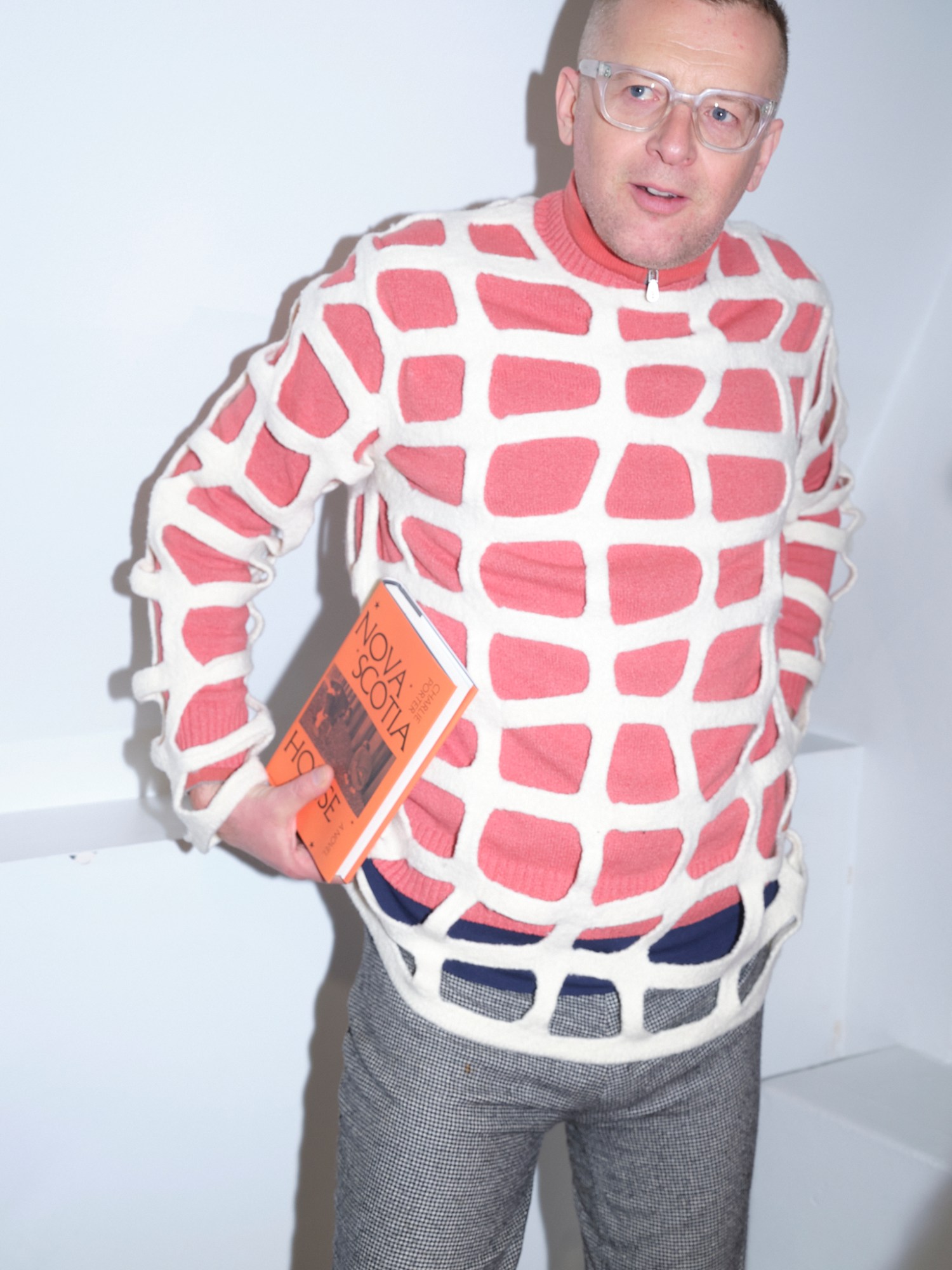

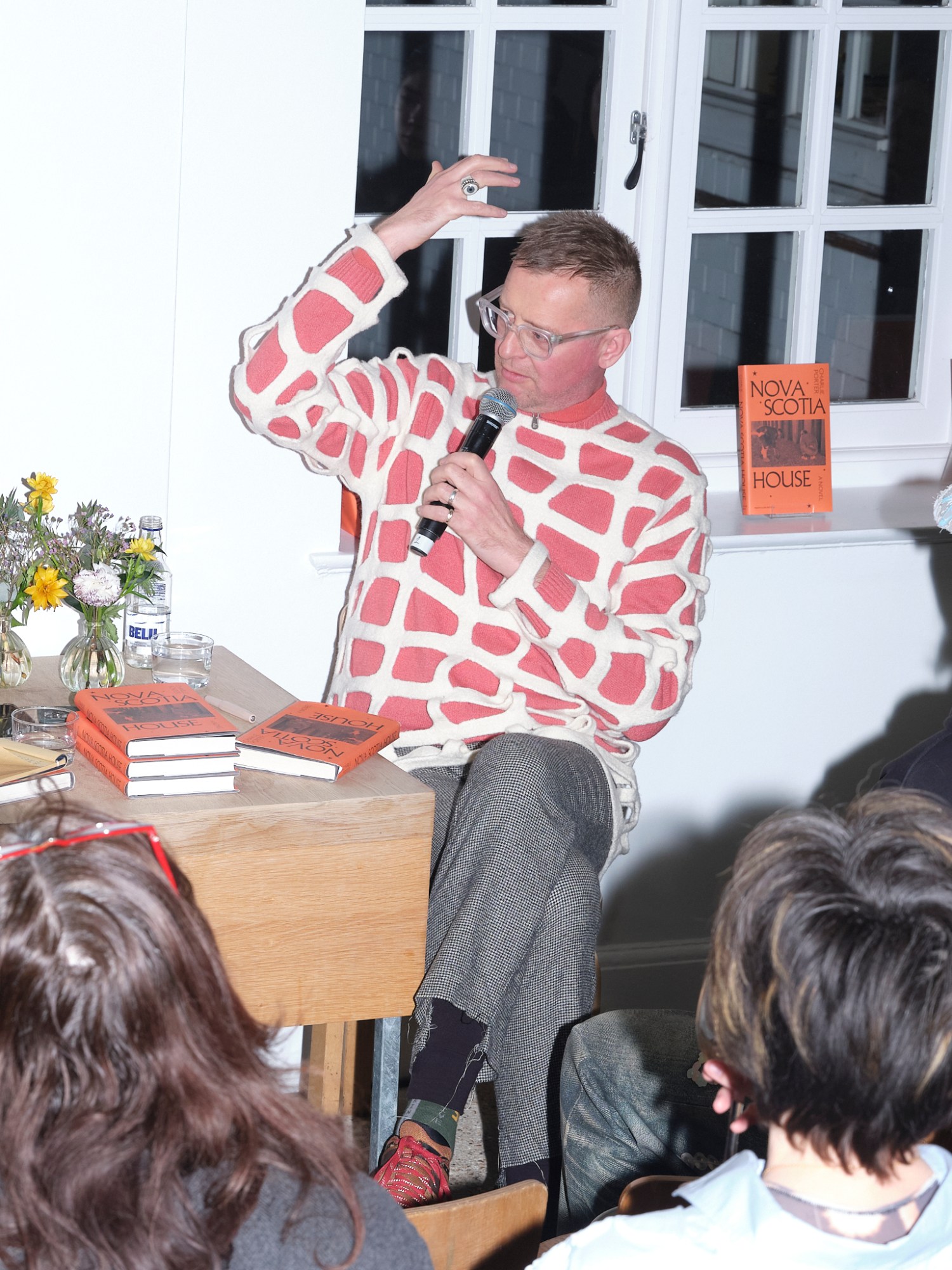

My new novel, Nova Scotia House, is an attempt to reconnect with queer experiments in living and with radical creativity, both of which have been jeopardised by the AIDS crisis. The point is to shine light on all who were lost, to allow space to grieve, and then to activate today. I like my books to be an open invitation to the reader to think about their own life and situation: What else can you do?

I’m saying this to myself as much as I am to the reader. I’m 51. I did not die young. What can I do now? How can I push back the parameters of life so that I can live my queerness as fully as possible? What are the societal structures that have previously confined me—structures which also confine those born in the decades after me? Is it possible to live in different ways, open-heartedly, breaking from heteronormative assumptions?

It sounds so big, so impossible, so unachievable. And yet, it also sounds so close, so possible, so alive. I wrote Nova Scotia House to test and challenge myself—because what else are you going to do? Keep carrying on like everything is normal? As if “normal” is even a goal?

There is such urgency. We have no time. If we reconnect with ways of being, which should always have been able to thrive, maybe we have a chance.

photographer Jordan Core for Dover Street Market London

Nova Scotia House is available now from Dover Street Market and all good bookshops.