Just over 30 years ago, in 1985, Tipper Gore bought her daughter Karenna a copy of Prince’s multi-platinum opus Purple Rain. But when Gore heard her 11-year-old listening to “Darling Nikki”— the scintillating sex-positive cut that closes out the record’s A side — the future Second Lady tried to return the CD, an unsuccessful effort since it had been opened and played. This lead Gore to co-found the Parents Music Resource Center, the organization that successfully lobbied record companies to slap “Parental Advisory” stickers across albums containing “explicit content,” (a now iconic label that graced Alexander Wang’s spring/summer 14 runway). It marked a crucial moment: the creative inheritors to the sexual liberation of the 70s found themselves squaring off against the institutional guardians of “family values” politics — a cultural clash that defined much of the decade and still profoundly shapes American life today.

Prior to the PMRC’s Senate hearing on “porn rock” — during which Frank Zappa memorably testified in front of a Congressional committee— the organization released the Filthy Fifteen, a list of songs they found most objectionable. The list called out themes of drug and alcohol use (Black Sabbath’s “Trash”), violence (Twisted Sister’s “We’re Not Gonna Take It), and the occult (Venom’s “Possessed”), but mostly, sex. Ten of the list’s 15 songs were condemned for containing lyrics pertaining to sex or masturbation, and the artists ranged from Judas Priest and AC/DC to Madonna and Cyndi Lauper. But “Darling Nikki” topped them all.

Reading Madge and Lauper’s lyrics, it’s not hard to tell what they were getting at on “Dress You Up” and “She-Bop,” respectively. But their depictions of sex — however autonomous or positive — differed crucially from the Purple One’s. Lauper’s proggy, synth-laden “She-Bop,” arrived with a highly stylized and humorous music video set at an atomic 50s burger joint; Madonna’s up-tempo dance-pop “Dress You Up” dressed up the song’s meaning in a (literally) thinly veiled fashion motif. “Darling Nikki,” however, does not insinuate, imply, metaphorize, or even wink. Sonically and lyrically, it’s a stark, direct, and unabashed depiction of dominant female sexuality — belted by a man who often rocked full lace catsuits and high-heel boots.

“Darling Nikki” performance scene from Purple Rain.

In “Darling Nikki,” Prince shares his story of a one-night-stand about a “sex fiend” he met “in a hotel lobby masturbating with a magazine.” She took him home to her “castle” where he discovered “she had so many devices, everything that money could buy.” When he woke up the next morning, she’d left her “phone number on the stairs/ It said thank you for a funky time/ Call me up whenever you want to grind.” Though the song contains lightning quick electric licks and propulsive percussion during its chorus and bridge, its instrumentals are pretty sparse when Prince actually sings its verses. He literally lays bare Nikki’s dominance — the combined result of her sexual prowess and her economic autonomy. In doing so, Prince demonstrates the logic of his own singular style.

Prince was not, as the Daily Beast’s Tim Teeman argued, “a teasing sartorial gender-blender like Bowie, but something tougher and grittier.” He didn’t strive to explode the gender binary (actually, he was a rather conservative Christian who opposed gay marriage), but subvert and reconfigure its conventional truisms through transactions of sexual power. Just like “Darling Nikki,” many of Prince’s tracks — including “Raspberry Beret,” “Do Me Baby,” and “Scandalous” — speak about the pleasure he derives from being sexually submissive to strong, dominant women.

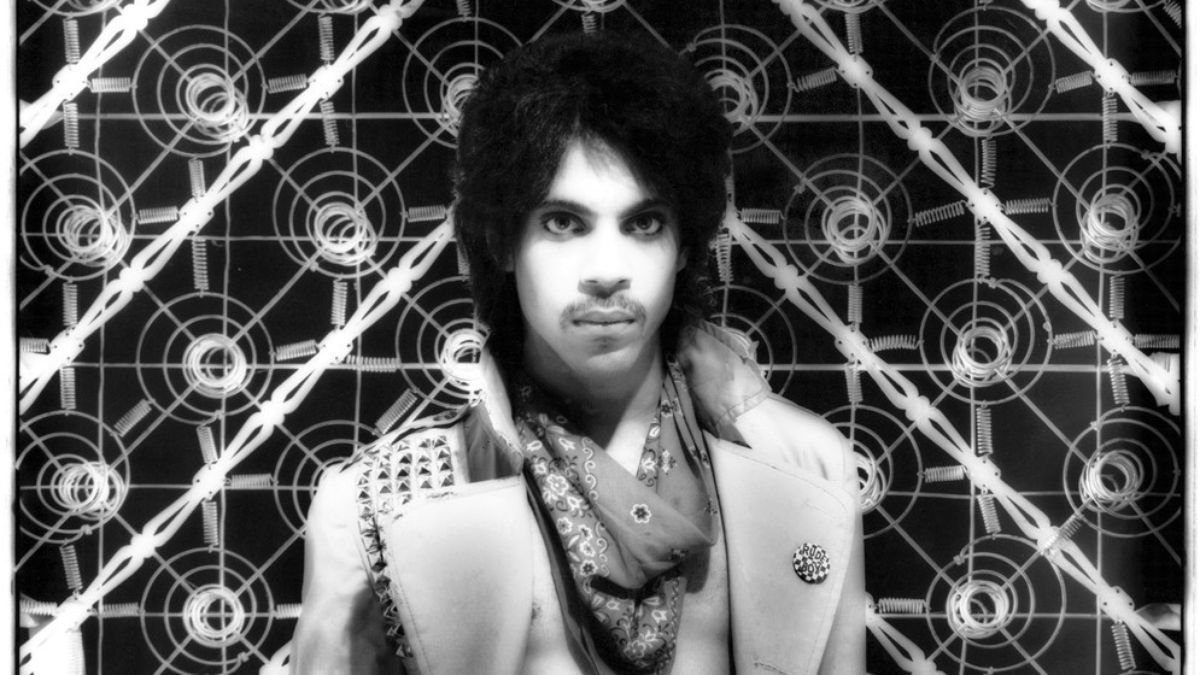

Prince fashioned a similarly bold new notion of masculinity through his wardrobe. The trappings of women’s clothing — silk, lace, ruffles, feathers, lamé, pussy bows, sequins, satin gloves, and polka dots — played a central role in defining and shaping his own masculine self-expression. “In the way he assumed the tropes of kitsch femininity,” Vanessa Friedman noted in the New York Times, “and transformed them into the vehicles of an in-your-face masculine sex appeal, Prince had enormous influence.” Especially during his mid 80s hey-day, Prince’s hypersexual style assumed a resplendent, regal opulence — as much an embodiment of power as his tight pants and plunging necklines. Is it any wonder that “Darling Nikki” and “Material Girl” — rich and enduring meditations on the intersection of sex and economics — both arrived in 1984, a year in which Dynasty was the most watched television show in America? When Balmain’s Olivier Rousteing played with 80s power dressing for fall/winter 2013, his maximalist collection simultaneously recalled images of the soap opera’s Carrington clan, and his Purpleness.

Though Prince didn’t testify with Zappa, John Denver, or Dee Snyder in those Congressional PMRC hearings, his music directly impacted American politics. While his legacy remains largely unmatched, there are men creating music today who directly interface with sex, cash, and power through such an electrically subversive combination of sound and fearlessly feminine style — Young Thug and Mykki Blanco come to mind. Still more lift inspiration from the Purple One in honing their own remarkably distinctive, fluid sounds, like Blood Orange’s Devonte Hynes, Years & Years’ Olly Alexander, and crucially, Frank Ocean, who yesterday penned a moving tribute to the fallen icon on Tumblr. “HE WAS A STRAIGHT BLACK MAN WHO PLAYED HIS FIRST TELEVISED SET IN BIKINI BOTTOMS AND KNEE HIGH HEELED BOOTS, EPIC,” Ocean wrote in an all-caps post. “HE MADE ME FEEL MORE COMFORTABLE WITH HOW I IDENTIFY SEXUALLY SIMPLY BY HIS DISPLAY OF FREEDOM FROM AND IRREVERENCE FOR OBVIOUSLY ARCHAIC IDEAS LIKE GENDER CONFORMITY.”

Credits

Text Emily Manning

Dirty Mind album cover via YouTube