Moises Saman was trying to move to Latin America in late 2010 as the first rumblings of the dissent began in North Africa. The Spanish Magnum photographer had spent much of his career photographing the people and politics of the Arab world and wanted to get away, to shoot and experience something different. But in early 2011 the New York Times sent him back, to Tunisia, initially just for a short assignment to cover the protest that was stirring in the region.

In January of 2011 a Tunisian street vendor, Mohamed Bouazizi, set himself on fire as a protest against the humiliations and harassments he suffered at the hands of the government. This act sparked a wider protest, which quickly became a full blown civil uprising, and within weeks the Tunisian President had been deposed and fled the country.

The Tunisian revolution spread quickly, first across North Africa, to Libya and Egypt, then to the Middle East, Syria, Yemen and Bahrain. By the summer most of the Arab world was convulsing in political violence, protest, disobedience, and civil war. Moises, instead of leaving, stayed, and spent the next four years criss-crossing the region, chasing the Arab Spring as the dream of freedom became grim reality, as utopia collapsed into dystopia. Moises moved to Cairo and was shot at by snipers, he was beaten by police in Tunisia, survived helicopter crashes in Iraq, witnessed the massacres of Tahrir Square, and saw the rebellion in Syria turn to civil war and horror.

“In the course of these years the many revolutions overlapped, and in my mind became one blur, one story in itself.” Moises says. The book he’s just about to release, titled Discordia, is a document of those years, but arranged neither chronologically or geographically, it is testament to that blur. The images tell the story of the Arab Spring emotionally, as an experience, rather than linearly, as something we can understand easily and digest.

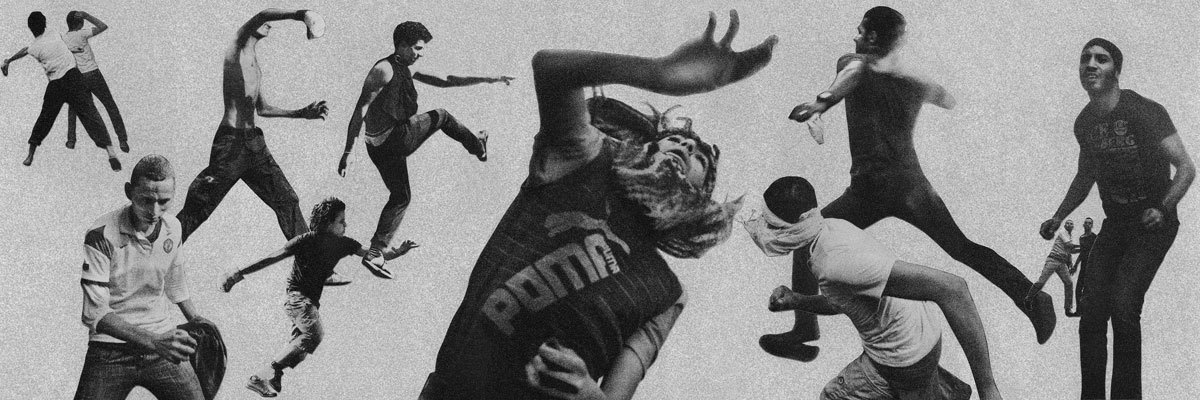

“I felt the need to transcend that journalistic language,” he explains, “and instead create a new narrative that combined the multitude of voices, emotions, and the lasting uncertainty I felt.” To this end, Moises enlisted Daria Birang, a Dutch-Iranian artist, to create a series of collages for the book. The images, culled the human bodies from his work, and replaced them stuck in the same poses, repeating the same gestures in different locations, across different times; throwing rocks, running away, white cut outs of people laid over the impenetrable mass of crowds, their silhouettes standing in for dead or the disappeared.

But Discordia is not simply an all action account of revolutionary freedom fighters overthrowing despots; this is war as a jumble of bodies, ideas, images, scenes, a confusing terrifying mess. Moises captures, not just the death and destruction, but the life that clung on amongst the rubble, the moments of humanity that survived the repression, the moments of peace just before and just after the action, this a document of absence as well as presence, boredom as well as fear, action and paralysis.

What initially drew you as a photojournalist to the Arab Spring? What was your first assignment?

It was fate I suppose. In fact, around the time when the revolution in Tunisia began, I was trying very hard to get away from the Arab world and move to Latin America, following an exhausting seven years covering the war in Iraq. Then my editor at The New York Times asked me to go to Tunisia for a short assignment, to replace a photographer that was already on the ground. No one predicted what came next.

Can you remember what your first emotional reaction to the Arab Spring was?

Anger. Shortly after arriving in Tunisia I witnessed a scene in which a group of plain-clothes policemen were beating a man in a dark alleyway. When the policemen saw me trying to take a picture they turned their attention toward me, and I was also beaten.

The Arab Spring was documented, not just by photojournalists, but by everyone on the streets with a smart phone. Do you feel that has changed the role of the photojournalist?

I think that our role as photojournalists is to challenge and critique any version of reality that is given to us at face value. We have to provide context, doing so with a level of sensitivity that comes from an understanding of the issues and respect for our subjects. In my opinion the smart phone/digital camera phenomenon has allowed for an unprecedented level of access to moments and events that otherwise would have been only experienced by the people present. However, context is still necessary in order to understand, or even question, the meaning of what you are looking at.

What was it like, chasing the uprisings, between Libya, Egypt and Syria? Thrilling? Terrifying? The essay speaks of many moments of danger you encountered, but what draws you to continue to shoot and document?

It was hectic; the pace was too fast for me to have any real perspective while I was immersed in the story. There were moments of chaos, sadness, anger, humour, sometimes all at once or in rapid succession. Moving to Cairo was an expression of my commitment to the story, and this commitment became in itself a source of motivation. I was certainly not braver than anybody else, or impervious to danger.

Many of the images seem to show quiet, moments after or before action, what do you feel this kind of image can show that images of shocking scenes can’t?

I think they are more engaging, because these “un-finished” photographs leave the door open to ambiguity and interpretation, allowing for a dialogue with the viewer. These quiet photographs allowed the narrative to weave in different directions.

The images are not arranged geographically, or chronologically, why did you take this approach?

I wanted the book to transcend a particular event or location, instead creating a visual rhythm that spoke about the larger experience, in the same frenzied manner in which I was working. In the course of these years the many revolutions overlapped and in my mind became one blur, one story in itself.

Do you think the Arab spring is “over” – is this why you are making the book now?

It simply took me this long to understand what I wanted to say, or rather, to understand how to visually communicate the various competing emotions, the ambiguity of some of the situations I encountered, and lasting questions that linger from my time in the region.

Can you say a little about the inspiration for the collages in the book? At what point did you decide on using them as a way to tell the story?

The idea came from Daria Birang, a Dutch-Iranian artist and close collaborator that has also been involved in the editing and sequencing of the photographs in the book. The collages emerged from our dissatisfaction in portraying the protesters simply as the subjects of an action image, instead we became obsessed with their body language, the theatrics, and performance-like rituals that I saw repeated during the countless demonstrations and clashes that I photographed.

It is I suppose a very unusual technique for a photojournalist, to manipulate the truth of the image in such a way. Are you worried about that?

I disagree with your suggestion that the photographs in this book manipulate the truth of the image, whatever ones definition of “truth” is. Each photograph represents an unadultered moment, photographed strictly in the context of real events and encounters. Only in the editing and sequencing process of the book do I create my own “truth”, by building a visual narrative that reflects the story in the manner that I experienced it, with the same intensity, ambiguity, and honesty, and for that I am solely responsible.

How would you describe Discordia?

Discordia is not a first draft of history, nor do the photographs intend to lecture the viewer about the complexities of the Middle East. It is an up-close and honest visual record of the time I spent living and working as a photojournalist in the Middle East.

What reaction are you hoping for from Discordia?

It’s hard to predict a reaction, especially since Discordia puts forward more questions than answers. However, I hope the book makes people feel the intensity of the period, which include moments of horror, sadness, love, defiance, comedy, and dignity.

Which events of the Arab Spring stick out in your memory most vividly?

The tragic loss of my friends and colleagues.

And equally what are the images that stand out for you in the book?

It may be that I am emotionally attached to some particular photographs more than others, but I believe that no single image in the book encapsulates what the book is about, the larger narrative, if detached from the rest.

Credits

Text Felix Petty

Photography © Moises Saman/Magnum Photos

Lead image “A Qaddafi supporter holds a portrait of the Libyan leader as fireworks go up in the background on a soccer field in a suburb of Zawiyah where government minders took a group of foreign journalists to attend a staged celebration.” Libya. March 9, 2011 © Moises Saman/Magnum Photos