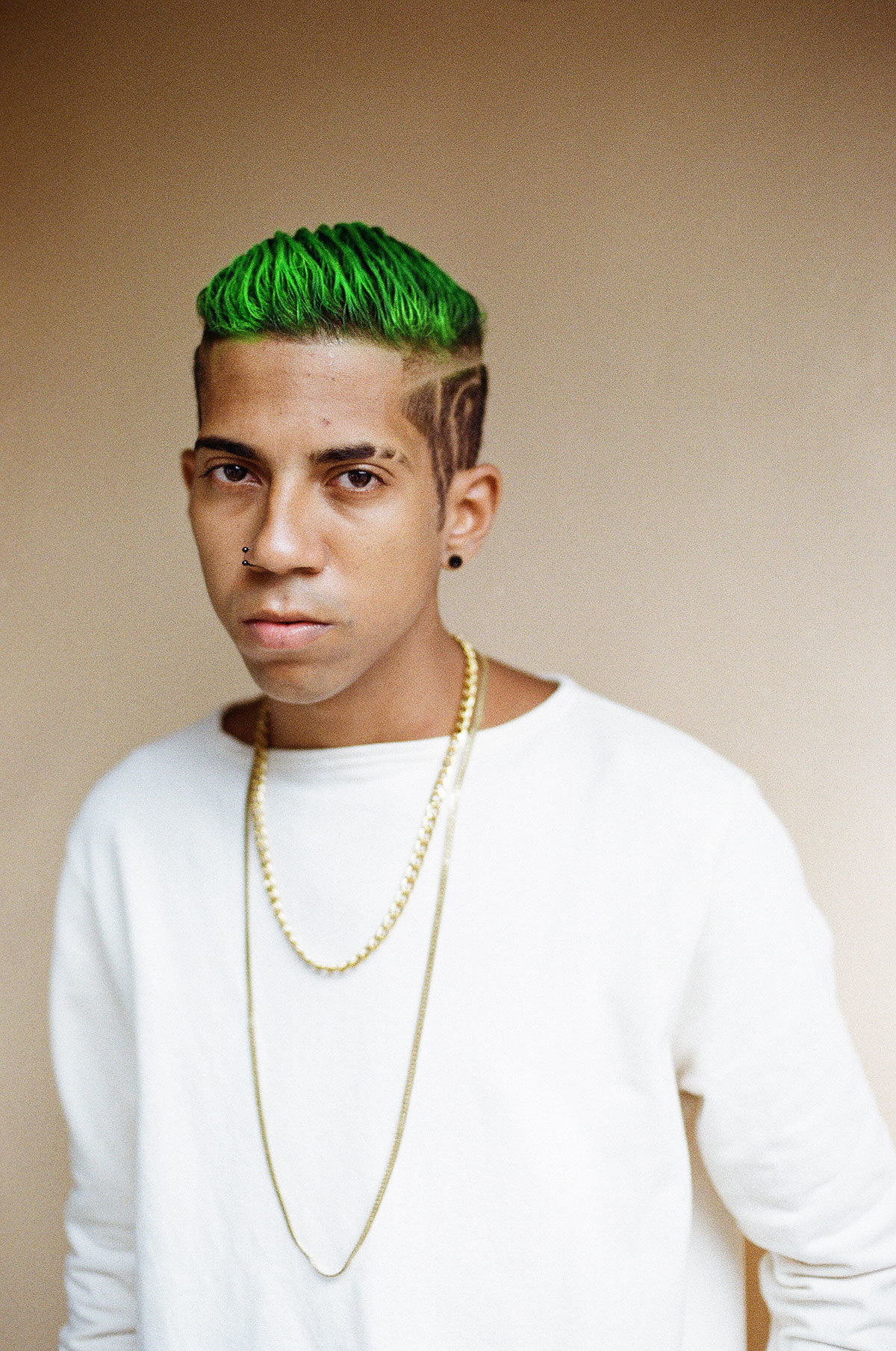

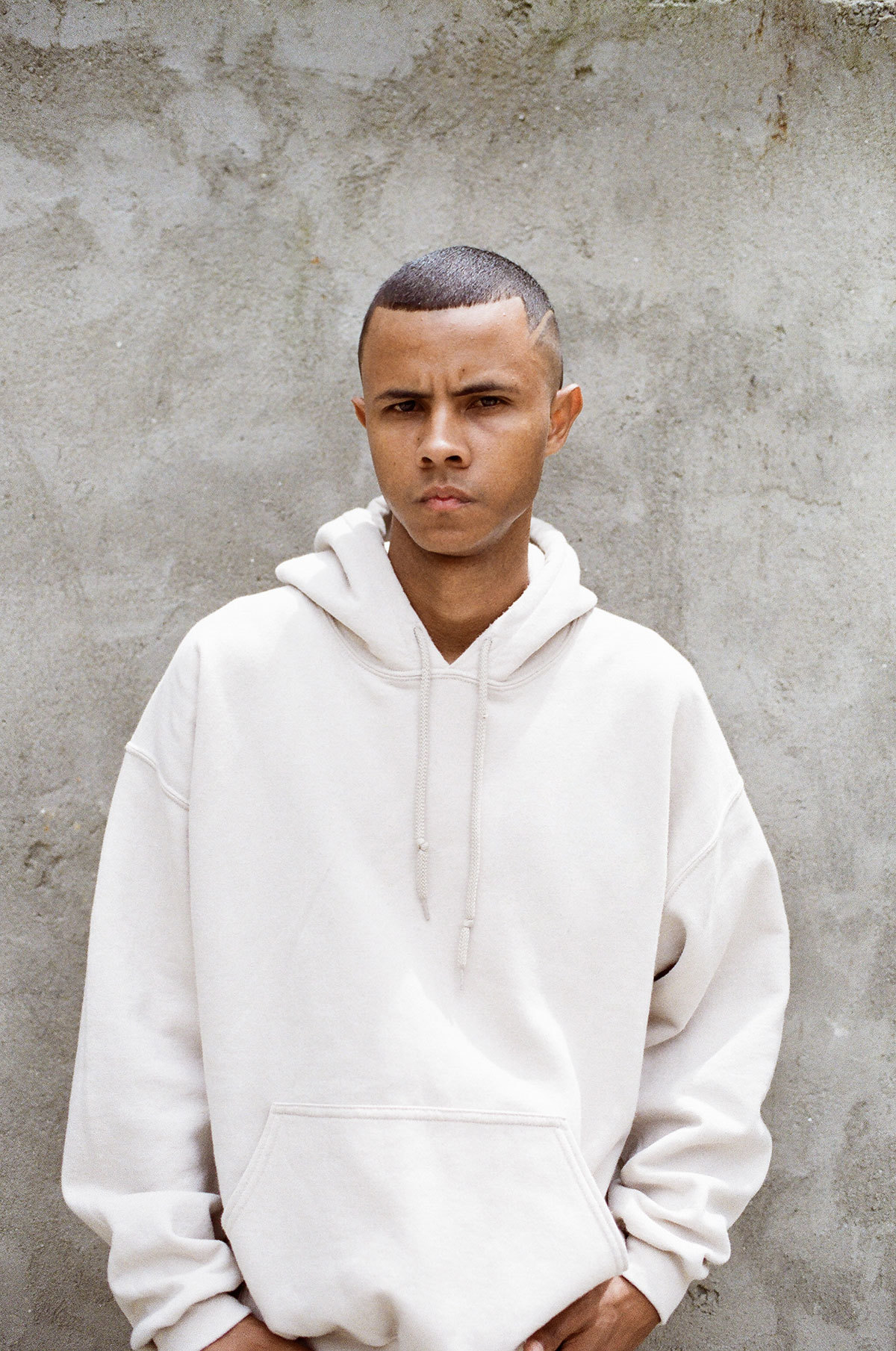

Hick Duarte’s photographs from the favelas are not just a document of a Brazil’s much maligned cities within cities. They are, like the haircuts of the boys pictured, all about the details. A certain fade here, a gently razored contour there, the crumble of a wall serving as a tell-tale sign of the poverty that lurks around every corner. More than anything though, the São Paulo-based photographer’s images are a marker of the transformative power of a haircut. That ability to elevate oneself above one’s surrounding by the fact that you look sharp and feel even sharper: something the Baile funk-listening Chavoso know an awful lot about. It came from the suburbs (didn’t it always?). Check out the pictures, and our interview with Hick, below.

When did you first decide to start shooting barbershops?

Actually, this is my second experience with barbershops. The first one was in September 2014, when I shot a series about the Run-D.M.C. legacy in Hollis, Queens. The most important subject we found was in a barber shop — a very close friend of Jam Master Jay who used to travel with the guys (he followed the whole Raising Hell tour!). It made me think about the importance of barbershops in a community context so, in January of this year, I called my friends Yuri and Carolina to help document the explosion of Chavoso style in Brazil.

Can you describe the favelas for someone who has never been?

Favelas are kind of informal neighborhoods located on the outskirts of the city. They grow offhand and organically, according to the number of families that go there (often compromising the provision of basic services). The streets are very tight. In many, it’s impossible to drive. Some are colorful, full of graffiti, others are more brutal, colored only by the tone of the building materials. But favelas are also creative centers, incubators for a lot of movements that influence other layers of Brazilian society. They’re very independent. They have their own rules and social organizations, as well as their own entertainment universes (for music, fashion, art, etc).

Who are the Chavoso? What does the word mean?

Chavoso is the word that the boys in the suburbs use to point out who has a cool look or a fresh outfit. It’s taken from “moleques chave” (key boys) and the term implies some common visual codes in the Baile funk scene, such as Juliet sunglasses, caps, golden chains, shirts and shorts from Oakley or Quiksilver, socks that extends to the shin, specific haircuts.

“Chave” means “key” in Portuguese and many say that the origin of the word comes from “key chain,” implying the Chavosos were guys who caused more trouble for the police. This is an interpretation that suggests a kind of “marginal look,” but I don’t think people today still make this association. It’s developed more into a word to describe a specific aesthetic coming from the suburbs.

Can you tell us a little more about Baile funk and its position in Brazilian culture? Where exactly does the look come from?

Baile funk is now the most popular musical rhythm of Brazil. It’s consumed by the masses, it’s on the radio, on TV, on the outskirts, but also finds enthusiasts in several other scenes: in hip hop, electronic music, MPB (Brazilian popular music). Funk stopped being seen as just music and become a lifestyle, an aesthetic universe, an attitude. New MCs come up all the time in the outskirts and become giants at an incredible rate.

The Chavoso look is more connected to “ostentation funk,” which talks about the material goods of an MC: what he’s wearing, what he’s drinking, what he’s buying with the money he makes. But it’s Quiksilver or Oakley, not Givenchy or Balmain. Chevrolet, not Mercedes or Ferrari. It’s an ostentation that’s possible, contextualized.

What significance do barbershops carry in the favelas? How important is the relationship between young man and barber?

I can see two different meanings to the barbershop in the suburbs. The first is the sense of community. It is where young people meet to hang out, talk about life, have fun, make fun of each other, listen to funk. When I went to shoot the pictures, they were showing each other new songs, watching videos on their phones all the time (music that the “downtown parties” will only get months later).

Bom de Corte, for example, the barbershop where I took these photos, has a very clear social function. Vinicius is a guy who knows all the boys that go there, he accompanies them and knows everything that’s going on with one another. There’s a strong connection and he organizes monthly events to cut hair for free for those who can not afford.

As well, the barbershop connects children to their own aesthetic desires, even if unconsciously. That’s where their first ideas of style materialize. It’s like a tool to make them feel part of a scene, which is very visual and has its particular codes — the haircut being one of the strongest.

Similarly, how important is a good haircut? Were your subjects keen to show their’s off?

The haircut is as important as the rest of the look, but I see it as one of the strongest because it is natural, it is the head, the body itself, rather than an accessory such as a cap or a chain. It’s interesting how it reveals the personality of these boys — the more introverted make simpler designs, choose the “Chavoso Classic,” while the more daring write words on the head, make whole drawings, change their haircut every week.

What are the most common cuts you see?

The “corte na J” cut is the most famous. Vinicius told me that is the haircut of choice for six to ten year old boys. It’s called “corte na J” because the haircut takes the shape of the letter J, and instead of using the machine to cut, he uses Gillette. Some like to draw logos on the head too. A Nike swoosh, for example (which is linked to “ostentation funk” story).

Could you tell us a little more about some of the characters you met? What is life like for a young man growing up there?

They were very nice and fun, not serious at all. They were always joking with each other, laughing at something. They have a very particular sense of humor, lots of inside jokes, and if you’re ginger and your name is Yuri (as in the case of our film-maker), forget it. You’ll be forever known as Peter Pan and you’ll just have to deal with it.

Their lives still revolve around school, although the older ones also have to work to help at home. They see people they live closely with become successful MCs and I think it becomes a dream for many of them. If before these boys wanted to become a famous soccer player, today they want to be a huge MC.

They’re very brave and determined. There’s a desire to get better living conditions for their families, a better structure than which they grew up in. Those with more talent in communication create channels on YouTube or become celebrities on Vine and Instagram. And, at the same time, a lot of strength and foot on the ground is necessary to not get involved with drugs, a very seductive options in the favelas.

Is there a female equivalent?

Not with as distinct a look as the boys. The girls have their visual references in the scene as well, but they’re much more diverse.

If you could do a similar project in a different part of the world, where would you choose and why?

South Africa and the Congo. I’m very interested in hair as an essential element of style in African culture.

Credits

Photography Hick Duarte

Fashion direction Carolina Domingos

Special thanks Yuri Mira