It’s 6pm in Kabukicho, Tokyo’s red light district, and the giant Godzilla head that sits atop the Toho cinema complex roars on cue like a spectacular cuckoo clock, its jaws flashing white to note the hour. A few yards beyond, through the blazing backstreets of ramen stands and sex shops, Tokyo’s art crowd packs itself into an unassumingly tawdry building, buzzing with anticipation for the evening ahead. Chim↑Pom, the six-piece art collective and the so-called ‘enfants terribles’ of Tokyo’s art scene, have just opened the doors to their first large-scale exhibition in almost three years, and the excitement is palpable.

At the door to the exhibit, guests are required to sign a mysterious consent form absolving Chim↑Pom of any potential accidents that may occur. Once inside, it’s clear why: the exhibition is held across a four-storey death trap, with a 2.5 metre-square hole cut into the centre of the three upper floors, where the collective are exhibiting So See You Again Tomorrow, Too?, a comprehensive project drawing inspiration from Tokyo’s rapidly changing urban landscape. The exhibition is spread across multiple levels of the semi-derelict Kabukicho Promotion Association Building, a drab architectural eyesore compared to much of Tokyo’s glittering skyline. As part of the area’s ‘regeneration’ process in preparation for Tokyo Olympics in 2020, the building is set for demolition next month.

Interestingly, the venue’s destruction will be a defining moment in the project, because Chim↑Pom aren’t planning to remove the artwork before the building gets knocked down; instead, all is being surrendered to the wrecking ball. “After that, we will pick up the materials and fragments, and we will create something new,” Ryuta explains. The reassembled artwork will form another exhibition at Chim↑Pom’s gallery space in Koenji, currently scheduled for early 2017. “In art, it’s not just about keeping the material artwork,” says Ellie. “I’m far more excited about making this situation happen and seeing the demolition as part of the piece.”

The demolition is part of a bigger plan to rebuild Tokyo, and in many ways the city’s history is repeating itself. Kabukicho’s Promotion Association Building was constructed after the end of WWII, and was dedicated to oversee the district’s post-war renaissance: “At that time, Kabukicho completely disappeared [because of] bombing,” explains Ryuta. “Many local people were planning to rebuild the city, so they made this association, and they built it in 1964. That was also the year of the first Tokyo Olympics.” This year, after the building’s destruction, a replacement association will be built in its place in preparation for Tokyo’s 2020 games. This full-circle timing strikes a chord with the artists: “It was like fate or something,” laughs Ryuta.

The walls of the exhibition are covered in what first appears to be a mess of faded blue paint, but on closer inspection reveals physical blueprints of the old Association office. White shadows of desks, bookshelves and a clock are imprinted onto the walls using a UV lamp and light-sensitive paint. Blueprinting is a strong theme in the exhibition because of its association with drawing up the future of an urban space: “About ten years ago, the mayor of Tokyo made a plan to ‘cleanse’ Kabukicho, and so he kicked out a lot of the homeless people on the streets and made it harder to run ‘night businesses’ here,” explains Ryuta. “That’s the statement that they issued,” he says, indicating an official document the artists have blueprinted onto the wall. The district’s proposed gentrification was part of a bigger plan to secure Tokyo as the city to host the 2020 Olympics. As we now know, they succeeded.

Still, Chim↑Pom are keen to honour the district’s seedy history. “The sex industry is very important when thinking about Kabukicho,” says Ryuta. “We spent time researching sex workers here, and we just happened to find many call girls named Mirai, which means future.” To play on the concept of Kabukicho’s history and its future, the artists invited one of those call girls to make a blueprint of themselves. On a huge blue canvas, Mirai’s naked silhouette, glowing like a seraph, is scorched white onto the canvas.

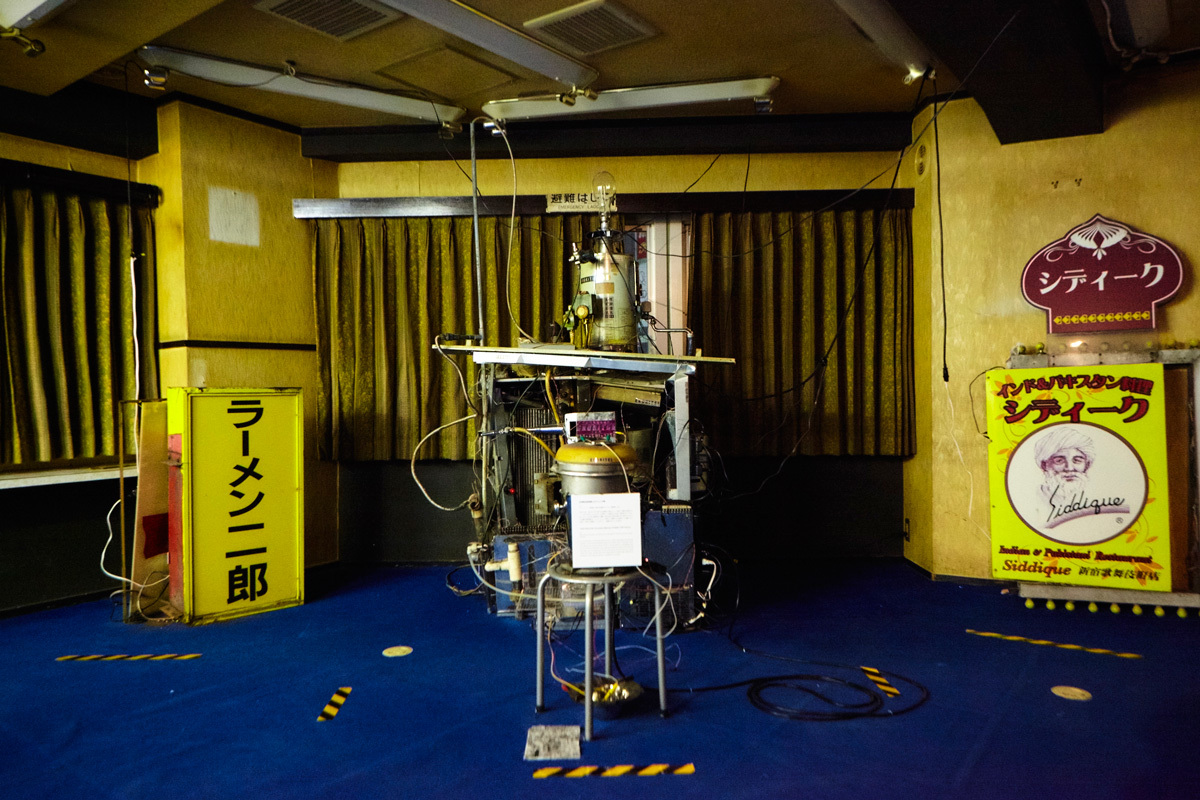

Other works include an interpretation of the Olympic rings created by paint-loaded cleaning robots (simultaneously cleaning and painting in an endless cycle), an ‘erotic-conversion’ machine that lights up whenever someone calls the imposter sex-line ad that Chim Pom placed in a few sports newspapers, and an intricate diorama of Kabukicho dominated by taxidermied rats that the group have painted to resemble Pikachu. The latter is a take on their earlier work Super Rat (2006), but the rats’ reappearance at this exhibit is still appropriate: “To survive in the changing city, the Tokyo rats have evolved to become stronger and smarter,” says Ryuta. Virtually immune to poison and too clever to be caught by modern traps, the artists had to catch them using nets and their hands. “We observed their behaviour for two weeks, and then one night, we captured them.”

At the bottom of the exhibition is the largest work, BuildBurger, a sculpture comprised of furniture and rubble from the building, sandwiched together under the cut-out squares of concrete from the floors above, the fast-food reference a metaphor for the consumerist culture that also permeates urban planning in Tokyo and drives its perpetual reconstruction.

Although the exhibition might easily be misconstrued as a protest against the city’s change and gentrification, Chim↑Pom aren’t quite as predictable as that. “I don’t judge it,” says Ryuta. “This is Tokyo government’s problem and not mine. It cannot be helped.” What is important, he says, is identity – the work they have created conveys the idea of Tokyo’s identity as an inconsistent beast. Despite the problematic ‘cleanups’ behind the building’s planned demolition, it has given the artists a rare opportunity to create an ephemeral space where they can express this sentiment.

This is something they are keen to share with everyone, and the collective have invited a range of underground musicians and artists to give live performances and talk-events. “We chose performers who are people that Chim↑Pom are able to work with and collaborate with, and we have a mutual respect for each other,” said Ellie. “We want the performers to be able to use this space to challenge themselves too.” The acts on so far have been refreshingly uninhibited: KOM_I, a Japanese pop idol, performed a set in the street outside dressed in a Pikachu onesie, and stopped traffic with the gigantic inflatable Pokéball rolling behind her, and the mosher-punks Nature Danger Gang swung on the rafters and crowd-surfed while eating ramen noodles in the building’s grimy basement. Despite the heavy message of cultural change behind the project, this focus on liberation and fun is exactly what makes Chim↑Pom special, and the exhibition and performances were packed with people genuinely thrilled to be there. That’s something you can’t knock down.

Credits

Text Ashley Clarke

Photography Takao Iwasawa