There have been lots of pictures of Christina Ricci recently in magazines and newspapers, pictures of her on the red carpet or front row or in the fog of Donatella V’s fag smoke, in orbit with the other celebrity satellites. “I really like all that,” she enthuses. “I really like clothes. And it’s really fun to go out and be a celebrity for an evening because my real life doesn’t feel that glamorous.” This is not what you might expect.

There are pictures of Ricci self-promoting, smiling, hair all slick, not a scowl or mention of incest, self-harm, firearms, eating disorders, angst, psychic scarring or any other suggestions that America is manifestly gothic to the core which is, of course, what we had come to expect of her. But Ricci is remaking herself and leaving her old self behind. “I realized as I got older that I wasn’t this grumpy misanthrope any more and I wanted my press to reflect that,” she says with a giggle. “I was like that a couple of years ago but I’m not like that now. Nobody wants the image of themselves at 17 to stick with them for life. That isn’t fun.”

The grumpy misanthrope was fun though, wasn’t she? If not always in a nice or entirely comfortable way. Ricci was the child star who stayed the course, though it looked like she might not, and talked us through it. We watched her grow and throw fits and say stupid things and thought it was so great that we demanded she do it again. Wasn’t she a gothic gas, lewd and leering and sneering with her big pale face bruised with the warpaint of teenage rebellion? Wasn’t she a scream?

We wouldn’t let Ricci stop being little Wednesday Addams, so perfect was her gloomy little monster. We wanted her to take Wednesday into the real world and scare people, which is kind of what she did. We willed her to grow up deliciously disjointed and dysfunctional.

And there was something even darker to all this. Ricci’s were more than generic teenage noises right? Maybe they were the sound of a person and personality being bent and beaten out of shape by modern celebrity and wasn’t that terribly fascinating? She was the anti-Ron Howard, the anti-Jodie Foster. She was letting us in on the horror of growing up in those conditions.

Ricci says all of that is wrong. That her teenage angst was standard issue. “All my friends were doing the same things,” she has said. “I just think that there hadn’t been that many teen actresses who had said that stuff in the press.” And the shocking stuff, the stuff about wanting a rifle and seeing incest as somehow cool; well, what do you expect a stroppy teenager to say if you keep giving her attention and magazine real estate and asking her silly or patronizing questions?

“I became outrageous because I would sit in interviews and get really irritated by stupid questions. That’s when I started saying crazy things. Eventually all the questions were like that because they wanted me to go off about something. I was a child being applauded for something so I would do it over and over until people stopped applauding. And it just became boring.”

And so Ricci has put away the potty-mouthed pubescent, which is fair enough given that she is now 22, can you believe, and a bit beyond all that stuff. What’s important to Ricci, and probably just, well, important is that she feels no sense of regret or that anything was really taken from her. She has had no horrible realization that her teenage years were offered up like some sacrifice. Her teenage angst was her own. We did not will it into being; we did not own it. And we did not know the half of it.

“No one knows the real shit I did when I was a teenager. The only things that were public were the things that I allowed to be public. It was never like everyone knows all these secrets about me. No one knows the real experiences that I had, because I haven’t allowed anyone to know them. My teenage years were my own. And whatever decisions I made, they were perfect for me at the time. What I said in the press and what I allowed to be public, that was perfect for me at the time.”

It is important now though that she move on and be seen to move on. And ditching that image, in a very deliberate fashion, is important because Ricci has plans that require burying the teen scream queen and burying her deep.

For all her indie credibility, Christina Ricci has never been the kind of actor who crows about venal suits and corporate automatons ignoring the integrity of her vision. She likes the industry, all of it, all its shady operations, the bullshitting, the wheeling and dealing, the pitching and playing. Pitching a project is her favorite thing.

Ricci has her own production company, Blaspheme (clever!), which is not unusual these days. What is unusual is how active the company is. She has produced or co-produced two movies. There is Pumpkin, a dark high school comedy in which Ricci plays the most-popular-girl-in-school who falls for the fellow student with serious if non-specific mental and physical disabilities, which has already been released in the States and should appear here next spring. And Prozac Nation, the film version of Elizabeth Wurtzel’s notorious downer diary, which should appear in the New Year. She is also producing, directing and starring in Speed Queen, a crime spree saga, and way on the back burner is Adrenalynn, a sci-fi blockbuster she is co-producing with Joel Silver.

Ricci is a proper littler mogulette who asks people to entrust her and her company with if not massive then considerable sums of money. And she does not want to be in a situation where others are asked to vouch for her mental stability, the kind of assurances the producers of Sleepy Hollow were after before they cast her. You see now why it was important to bury the teen Ricci.

It is still early days for Blaspheme. These movies, bar Adrenalynn, are low-budget and so relatively low risk. But Ricci is not playing at this. She doesn’t have much time for playing. “I’m no good at kicking back, it makes me feel like a lazy teenager. I like being crazy tired at the end of the day and having a ton of stuff to do. Acting isn’t really that demanding. The producing is a real job.” With 37 movies already to her credit — from commercial hits such as The Addams Family and Sleepy Hollow to cult favorites like Buffalo 66 and The Opposite of Sex — it is hard to deny Ricci’s work ethic.

There is clearly also a control thing going on. “If you are just acting in a movie then you have no other business with the movie. If you don’t like what’s happening, you just have to bite your lip and try not to see that there might be another way of doing whatever you are trying to do. But if I’m a producer, I have a right to say, ‘why aren’t we trying it this way?'” Ricci has been around film sets since pre-adolescence and has clear ideas about how she likes things done. And producing and directing keep her deep inside the movie machine, 24/7. Which is just how she likes it. This is where she is comfortable and happy.

Ricci was a difficult little thing, causing trouble at school, railing against this and that, until she walked onto a film set and things were suddenly made better. She was nine years old. Her father was, amongst other things, a primal-scream therapist with a particularly gloomy prognosis of the human condition. Her mother was a model. Home life was not all it might have been. Her parents divorced when she was 13 and, though she remains close to her mother and three sisters, it seems she found on the film set an extended family who went out of their way to make her feel warm and happy and ready for the next take. She is still, in part perhaps, the little girl, applauded and fussed over for saying a bunch of words in the right order. “I still think people don’t expect much of me,” She admits.

The film set is where she grew up and where she feels most useful, functional, skilled, part of a bigger scheme and (potentially) benevolent social structure. “When you go on location, you can actually create a really sheltered little world,” she says. “On a film set there is such a sense of comfort and confidence. I know exactly what is expected and how far to push it.” The set will keep her safe from harm and this means that she will do things that scare the hell out of those around her.

Though it is yet to be released, Prozac Nation was finished a couple of years ago. There are various stories about the delay in release. One suggests that Ricci herself pushed back the release date after Elizabeth Wurtzel made some insensitive remarks about the 9/11 attacks. Wurtzel was quoted in the Toronto Globe and Mail claiming she felt no “emotional reaction” to the collapse of the Twin Towers, even though her apartment, which she was in at the time of the attack, was close enough to Ground Zero that her windows were blown in and chunks of aircraft fell on her roof. Wurtzel went on to describe the event as a “really strange art project” and how the towers fell like a “turtleneck going over someone’s head.” She also admitted annoyance that no one had called her to write about the attacks. (It seems more than possible that years of prescription medication and self-involvement might leave you in such a desensitized state.)

Ricci insists that she does not have the power to postpone the film’s release. “Miramax have total control there. And I think we have seen how timing can really affect a movie and Miramax certainly know what they are doing.” She has also leaped to Wurtzel’s defence. “I know she was accused of saying something and she says she didn’t say it. And I can’t imagine her saying that given that she’s a born and bred New Yorker and very sensitive and very emotional.” And Ricci should know.

Before the filming of Prozac Nation, a one-hour meeting was set up between Ricci and Wurtzel — the film’s other producers were clearly keen to limit the input of the author. Inevitably, though, the pair hit it off and spent an evening drinking and playing poker. “We talked about boys and our lives,” said Wurtzel. “A lot of Prozac Nation is really about people thinking you’re having a great life and you’re meeting boys and stuff when you’re just stuck in your room working on your own. Christina had just come out of a long-term relationship so she understood that. And although the book talks about an extreme emotional state, it’s really about depression and a lot of people can relate to that.

“More than anything I was relieved when I met Christina. So many names had been bandied about since the book came out: Sandra Bullock, Drew Barrymore, Alicia Silverstone. And the thing is that any actor can fake mental illness. Angelina Jolie has built a whole career out of it. But you can’t fake being smart. There was never a worry about that with Christina.”

But as much as Ricci and the author formed a mutual admiration society — and noted a spooky physical similarity — nothing in that meeting indicated how far Ricci was prepared to go to recreate the Wurtzel experience. “She wasn’t really intense at all when we met, just a sweet, natural kid. She didn’t ask a whole load of questions about the book or anything.” Wurtzel was surprised when reports came back from the set that Ricci was painting an all-too convincing picture of psychic meltdown.

Indeed, so thorough was Ricci’s investigation of her dark spaces that the film’s crew eventually threatened to walk out unless Prozac Nation‘s producers instructed Ricci to ease off. As Ricci saw it, it was what the film required. And she was always in control, even if those around her doubted it. Brad Weston, one of the film’s producers, says: “It seemed like a really fine line at the time but she’s intelligent. And she always knew there was this box in which she had to work, however big and scary that box seemed.”

Ricci has no regrets. “I’m really happy that I did it because it taught me my limits. Back then, I thought I had to do certain things to get that kind of role right. And the filming taught me what I actually need to go through and what I don’t. But it was a good experience for me. It taught me how to protect myself.”

There has always been that sense that Ricci — and Prozac Nation might be the extreme example — picks her roles in part to throw a klieg light on her inner drama, to jump-start some emotional upheaval and provide an eventual resolution. It might be that on the film set, the place that she feels most comfortable, doing the job, that she has made some mediated personal journey, role-playing her way through adolescence and beyond. Of Prozac Nation, she says: “It was definitely an important part of my growing up. I’m different now and people who knew me before really comment on it.”

Ricci is not sure about the role-as-personal-development theory but admits it sounds like a good idea. “I’m of an age where I like to think of everything I do as a step in the right direction, some chance for personal growth and all that bullshit. So to me something like Prozac is really worth it. And now I’ve done that, I don’t have to go through it again. The problem is that I don’t have any foresight, which is why I get myself into problems and find myself halfway through a movie thinking ‘what am I freaking out?’ I haven’t really sat down and looked for roles that would be personally useful for me but I’m starting to try.”

She accepts now that she needs to give herself a little more protection. Having production or direction duties helps, she says, gives her something else to focus on during filming. She also says she may look for “lighter” roles in the future. This seems like quite a shift for independent cinema’s princess of darkness. And even as a producer she admits it might be time to look for more palatable product. “There’s a lot of great ideas you come across form first-time writers and directors. But a lot of it is too difficult to get made; the subject matter is too extreme. I used to try and get those movies made but now I realize it’s unrealistic, for a small company like ours anyway.”

The problem for Christina Ricci might be that if she takes away too much shadow, she takes away the USP. An older, lighter, less damaged Ricci might find herself just one more “kooky” looking actress fighting for Reese Witherspoon’s scraps. As long as Witherspoon insists on remaking Legally Blonde over and over though, there will always be a place for Ricci. You wonder whether the all-conquering Witherspoon would taken on Pumpkin, for instance. And anyway, Ricci isn’t quite done with the darker side. “I love to do characters who the audience is supposed to hate. The thing that keeps me interested in all of this is the interest in human nature. And I think that people who are the biggest assholes are usually protecting something special.”

Credits

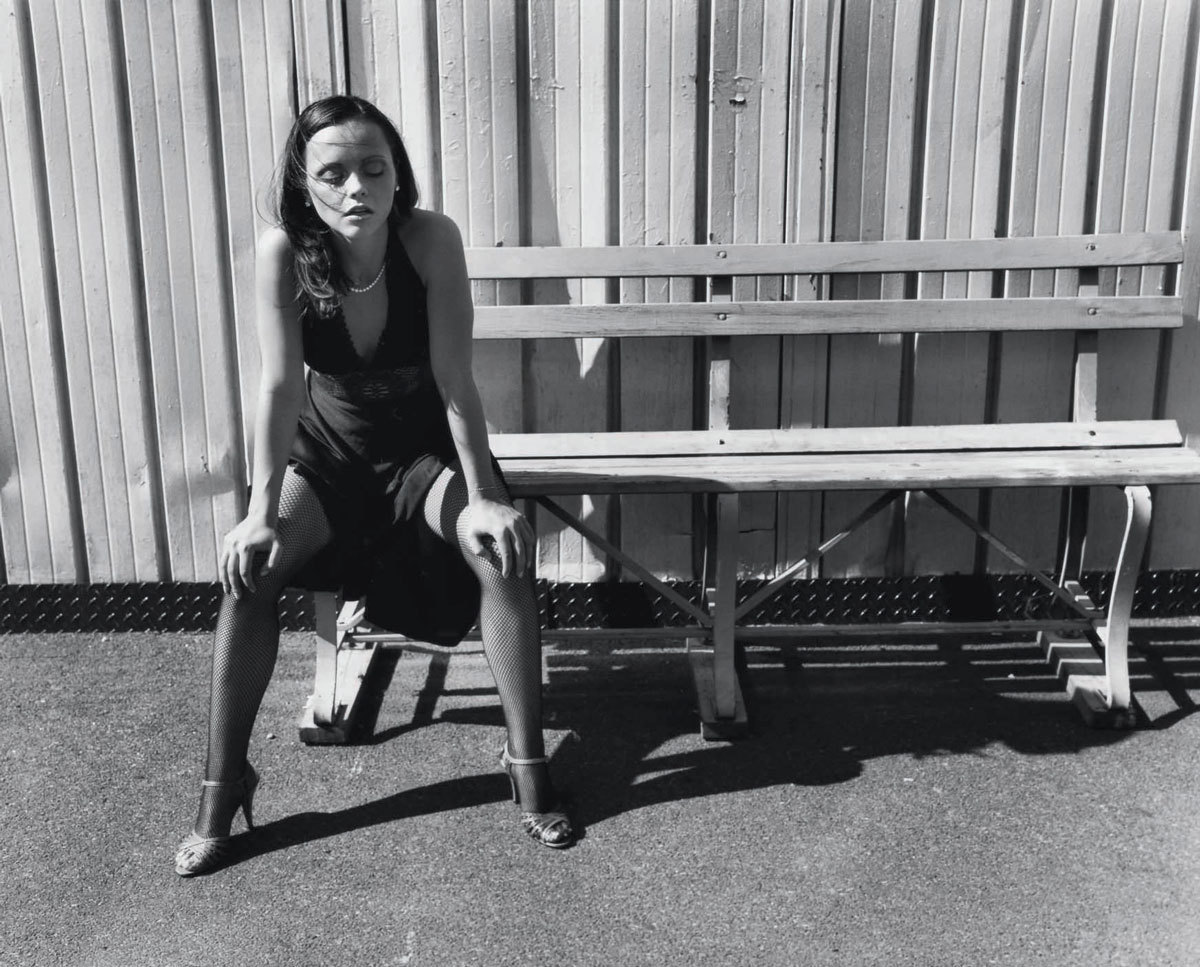

Interview Nick Compton

Photography Carter Smith

[The Cruise Issue, No. 226, December 2002]