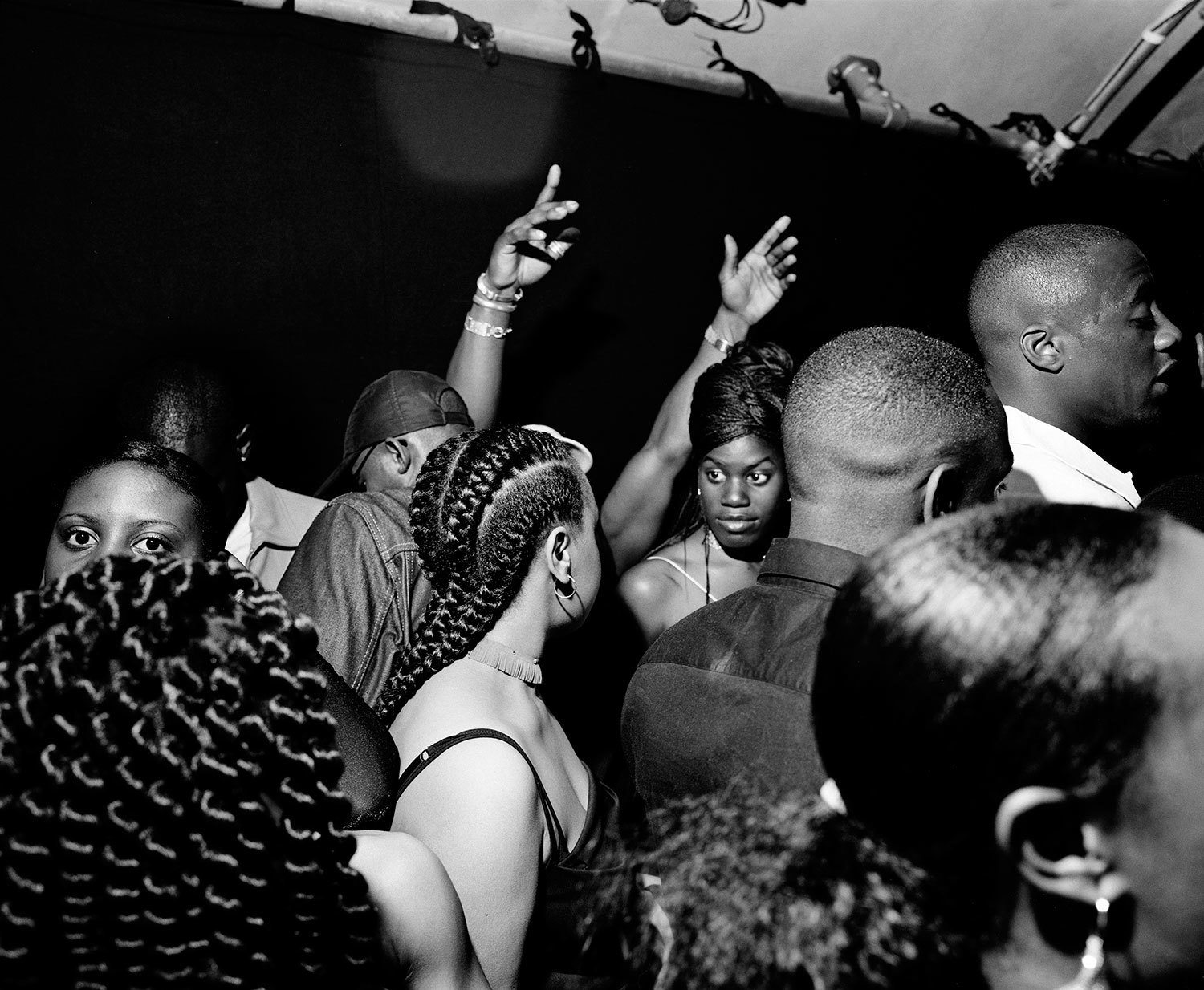

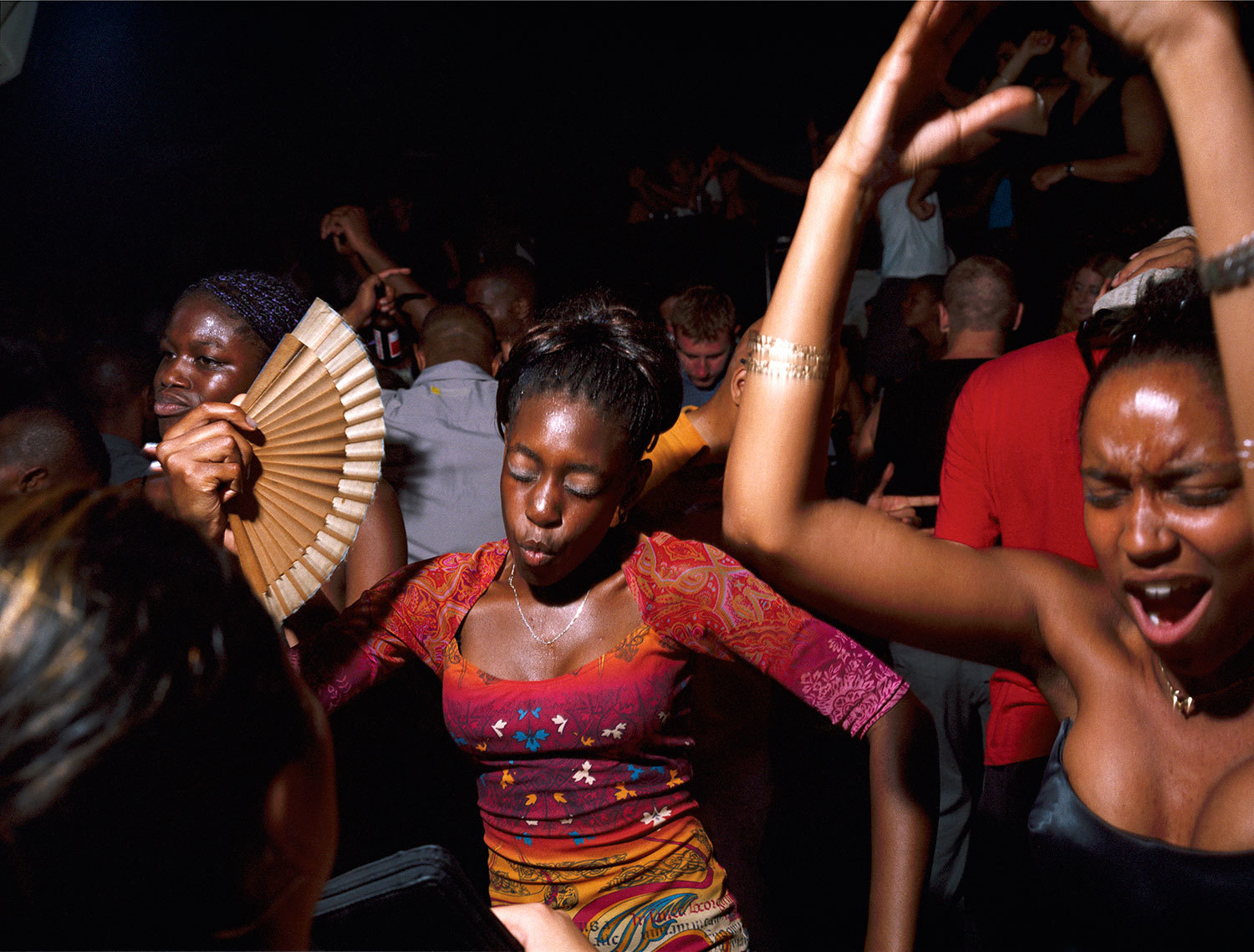

When the offer to work on an ambitious attempt to tell the story of how style and music come to form different style tribes, and how they’re all part of the same narrative called Street, Style & Sound came along, I knew it played into our shared obsession: youth culture. Ewen has been documenting it since the early days of Garage, moving into Grime, Happy Hardcore, Spring Break hoodlums and much more. I spent a weird few years of my life going to clubs on the outermost fringes of our culture. Together we spent a lot of hours on youtube finding strange videos of Rudeboys, Cybergoths and Fantazia car-park ravers. Somehow we made a TV series out of it.

With the series now finished and being serialised on i-D, I sat down with Ewen to talk about what we wanted to achieve with it, what we learnt, and our thoughts on youth culture and the sad people who say it ended in 1989.

Clive Martin: Ewen, so what did you want to achieve in this series?

Ewen Spencer: I wanted to achieve a slightly different take on the subject really, I just wanted to do something a bit personal, which was at first very achievable, until I think, it became a slightly different angle as the series went on, like in the final episode. Basically I hadn’t really experienced anything that was going on in the second half of the final episode, so it almost came full circle for me.

I’ve been a part of the Grime scene, Garage scene, I’ve witnessed Jungle, and everything before that. I’ve either seen, known someone or been a part of it in some way, so when I was first asked to do it, I just wanted to make sure I did it from quite an autobiographical point of view, and that’s how I approached it; that’s how I wrote it. I wanted to make sure it was done that way; there’s no point in me doing something like this unless it’s done in a legitimate way. I didn’t really want to be objective about it, I wanted to make it quite subjective and from my experience.

CM: Do you feel like it’s almost a culmination of something, like a body of work you’ve created over the years?

ES: Yeah, I mean, when it was first proposed, it felt like a lifetime’s work. This is what I’ve been looking at and thinking about since I was very young, so getting the opportunity to do it was very exciting.

I look at films and at documentaries, and I quite enjoy them, but they don’t really speak to me that well, so I felt like I needed to re-address a few things. Maybe those documentaries speak to other people really well, but I just felt like, given the opportunity, I would make it in the way I guess I made it, with the help of everybody else, because of course, there were a lot of people involved.

What did you think the outcome of this project would be?

CM: It basically turned out how I wanted it to, not totally comprehensive, because it’s kind of too subjective for that, but basically I wanted it to explain that with a lot of these things, that there’s a lineage, and there’s a history there, and they do kind of relate to each other and react to each other and it is a history.

I think people have written and made documentaries that touch on that, but we followed that lineage to the current day. It’s an ever-growing story I think.

ES: For the second half of the episode, there was something quite satisfying tacking the idea that youth is exciting, I was quite pleased to confirm the idea that young people are still creating interesting things, in a different way that I guess older people don’t get. Do you get that?

CM: Yeah, totally. I think one of the things we always set out to do is not to make it too BBC 4, too Stuart Maconie, and I think we achieved that.

ES: Haha yeah. I definitely didn’t want to make anything like that. They’re a different generation of people, and it’s all fine, and there’s probably a lot of people who want to see that, but, like I said, it really doesn’t speak to me, it always feels a bit nostalgic.

CM: There is a school of people who seem to believe that these things stopped in 1989, 1995, wherever the end of their interest in these sort of things stopped…

ES: I mean it’s quite common isn’t it, people think nothing exciting happened after their experience.

CM: Can you remember the first moment in your life you wanted to associate with a style tribe?

ES: It would have been an Adam and the Ants moment when I was probably about nine. That was very popular, on Top of the Pops and that came out of punk. My big brother and his friends were punks, so they were interested in Adam and the Ants in a slightly snooty way, but they were interested in the first track, not the second one that’s popular with everybody, so of course the one that was popular with everyobody was the one I quite liked, cause it was more accessible, more pop and more fun. So at that tender age I quickly changed to The Specials – I’d seen The Specials on TV, I’d seen the video by The Specials for Do Nothing, and I just really loved the sound of the song, and Terry Hall and the way he looked.

I guess at that time the kids at my school that were a few years older who were into that sound would have been what was either called a mod or a rude boy. Or a nutty boy, which was a Madness fan who just looked like a mod. They all looked the same really, they all had Fred Perrys, and V-necks and some of them wore parkas. That was the look, Sta-Prest, button downs, and brogues, that was the look, so that was my first entrance into that idea of tribes and being associated with something and trying to find your own autonomy, away from the restrictions of parents and school and youth club cub scout.

What was it for you?

CM: There was a brand of jeans called Bleu Bolts, they were very associated with skateboarding. I was never really a skateboarder but that was the look in the shopping centres of suburban South West London where I grew up.

It seemed to be a slightly rebel style, and there was a kind of impracticality to it. It was pre nu-metal and anything like that – it was more akin to the stuff you see in early Spike Jonze skate videos. It was the rebel statement du jour and I was attracted it cause everyone was wearing Adidas poppers and a lot of stuff that’s now come around to be very fashionable again. Unfortunately the Airwalk and the Bleu Bolts will never be in fashion again, but in context I think it’s very attractive to a 12-year-old to want to cause a bit of trouble with the way you dress.

ES: Yeah, it’s just trying to find your own place isn’t it? Your own identity, that’s what it’s about.

CM: What do you think forms youth cults more, style or music?

ES: I think it wouldn’t travel without music. I think music was totally integral to it. But now we have the internet, the access, and the ability to research so freely, that it’s less about music. What was it for you, do you think the music was the biggest part?

CM: 100% I think fashion is always doing its thing and music has the power to make certain parts of fashion cool. The clothing side of things is always a staple, and music can often be what makes certain brands or styles become relevant.

Look at someone like Yung Lean. Most of the stuff he wears is in pre-existence, it’s more about the context he and his crew will put that sort of thing in, which has attracted legions of kids.

ES: From walking around London and Brighton today, that’s what I’m seeing a lot of: groups of boys aged 15 and 16 with that look. There’s a big sports brand – almost retrogressive look at the moment.

CM: That whole Wavey Garms/Yung Lean thing is the most prominent modern subculture. That obsession with appropriating luxury brands.

ES: Well, luxury and sportswear. Some of the stuff looks quite working class in that way, but that’s always a part of it I guess, it’s the re-appropriation of something that’s unattainable within your financial realm and remit. That’s the idea isn’t it? It’s the aspirational part of it and we really love that in Britain, don’t we?

CM: Seems like we achieve that kind of authenticity by either buying it second hand or stealing it, as things like Wavey Garms and De-Pop have shown us. Nobody wants to look like a rich kid who has a trust fund that affords to spunk £200 on a jumper.

ES: The reality is, if you’re buying Supreme, Patta or all these other brands that are associated with a hip hop stance, they are very expensive and in short supply as well, which maintains their popularity, which is a great metaphor for late capitalism.

CM: Most of your work has dealt with youth culture, what is it that keeps you fascinated by it?

ES: It’s the fact that it’s always changing and moving on. That idea of trying to define yourself at a young age is always deemed quite fearful by older generations. There’s real purity in the creativity of it, that I really really enjoy and it really speaks to me, and it’s also fun to photograph and to capture, visually. Young people are coquettish in those moments of performance and to capture that and photograph that can be very rewarding. That kind of anarchy and self-governance of youth is very compelling.

CM: For me it feels like the cultural frontline. As a journalist it became clear pretty quickly that I was never going to go to Iraq or anything like that, so instead of just sitting around interviewing established DJ’s or designers or rappers or whoever, I enjoy dealing with people working on the front line of it.

Did you learn anything making this series? Were your perceptions changed at all?

ES: Not massively, what I was surprised by most was people’s absolute passion for it. I mean, I wasn’t sure people would be so in love with their clothes and their look, but people really do have massive love for it, and it kind of made me feel I wasn’t such a weirdo. What did you learn from it?

CM: I learned a lot in terms of the smaller details stuff, because I wasn’t alive for a lot of the stuff we covered, so for me it was a really interesting history lesson, but other than that it was just a really heartening reiteration of what I have always believed. I think I learnt how similar it all is, how it all plays into a narrative, despite the differences on the surface.

ES: Yeah it’s cyclical I think, it’s a rite of passage. That’s what I learnt from it. And it really assured me, and I hope it reassured other people that there are youth movements that matter.

CM: A lot of people say youth culture is dead blablabla, what do you think of that?

ES: I think I’ve made myself clear with this series that youth culture and subcultures are not dead, and they will keep happening. Some will take hold stronger than others, and they’ll become really recognised but as soon as they are recognised, that’s it, the game’s up and it’s over. As soon as we heard about UK garage and Twice as Nice, that was the beginning of the end for it. It’s no longer a couple of hundred of people, it’s a couple of thousand, the next month its twenty thousand, in six months it’s two hundred and twenty thousand… that’s how it works, but there are other subcultures out there and little movements that may only be a few thousand and they are still as interesting, still as compelling for me. Sometimes someone is there with a camera, or a note pad and a pen, and they record it or make a picture and then in ten, fifteen years, we look at the pictures and get really excited about it.

So of course it’s not dead and it never will be. It won’t be the same as it was for me or for you, but there will be something out there… you’re just a bundle of hormones trying to work things out. It’s always gonna be a confusing and conflicting, troubled sort of time for young people. As I’ve always said that element of youth is becoming extended, so it’s maybe not as confusing but we still remain younger for longer.

CM: I think it’s a pretty ridiculous thing to say that youth culture is dead, when you see gangs of kids dressing in a certain way. What is it if it’s not youth culture?

ES: In a way people saying it’s dead is a wonderful example of the fact that it’s not. It’s that you are getting older, and you are not a part of the youth culture anymore, which means that youth culture is happening somewhere else and that’s the way it should be.

CM: Thanks Ewen!

Watch Street, Sound and Style: Episode one Grime and Emo.

Credits

Text Clive Martin

Photography Ewen Spencer