When Collier Schorr was living in Schwäbisch Gmünd in the mid-90s, she had a friend who reminded her of skinheads back in New York. He wore Doc Martens, army jackets and suspenders, and rode around the southern German city on a Vespa. For Collier, a Queens native who became embedded in New York’s art scene during the mid-80s (first as a student, then writer, before taking up photography in the early 90s), the outfit held twin associations. It was the uniform of both the skinheads of the East Village, and the gay men in the West Village. She decided to try it for herself and went out and bought red Doc Martens at a shop in Stuttgart.

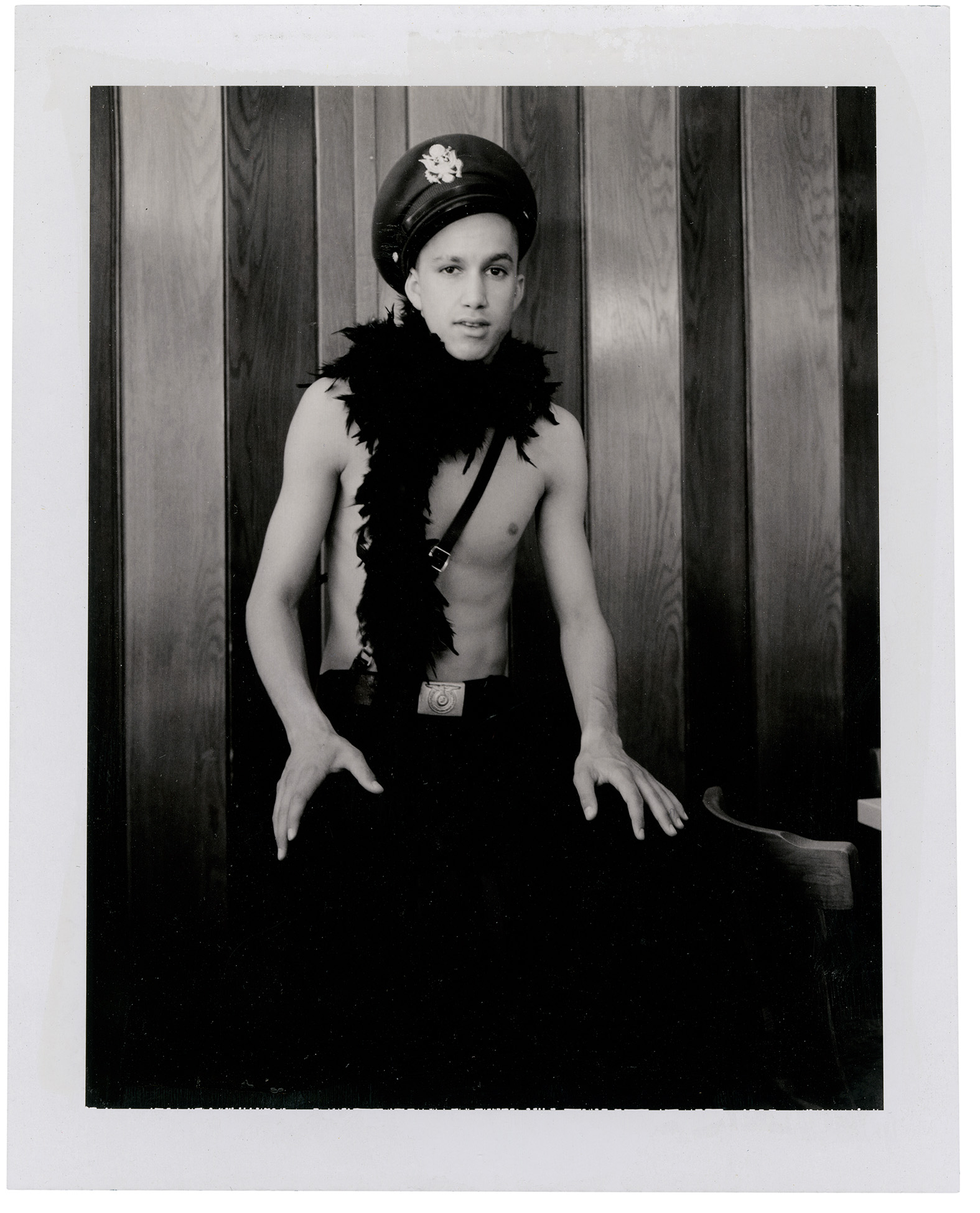

“I literally scared neighbours because I looked threatening,” Collier says. The clothing subcultures of New York — particularly the appropriation of military wear — held dramatically different associations in late-Soviet era West Germany. In her photography, Collier builds “a character through signifiers,” she says, manipulating what garments mean in other contexts (she had used clothes for sculptural works in the early-1990s). Collier’s own queerness provided an ambiguous mannequin on which to hang these ideas. “I’ve always believed that clothing told both a story and a lie,” she says. “I got to walk around with lots of different fantasies in my head, including being a boy, and none of them were true.”

Germany exposed her to a new set of stories, and even more lies. She had first visited Schwäbisch Gmünd with her then-girlfriend, returning each summer to the same community. She was the only Jew in a town of few Americans and even fewer queer people. Having grown up in New York, Collier was accustomed to the discussion of World War II’s atrocities against Jewish and gay people, interspersed with American triumphalism. She found German attitudes confusing in comparison. There was not a blanket burying of the past, but a lingering repression made outward nationalism taboo, silencing conversations around commemoration and ancestral responsibility.

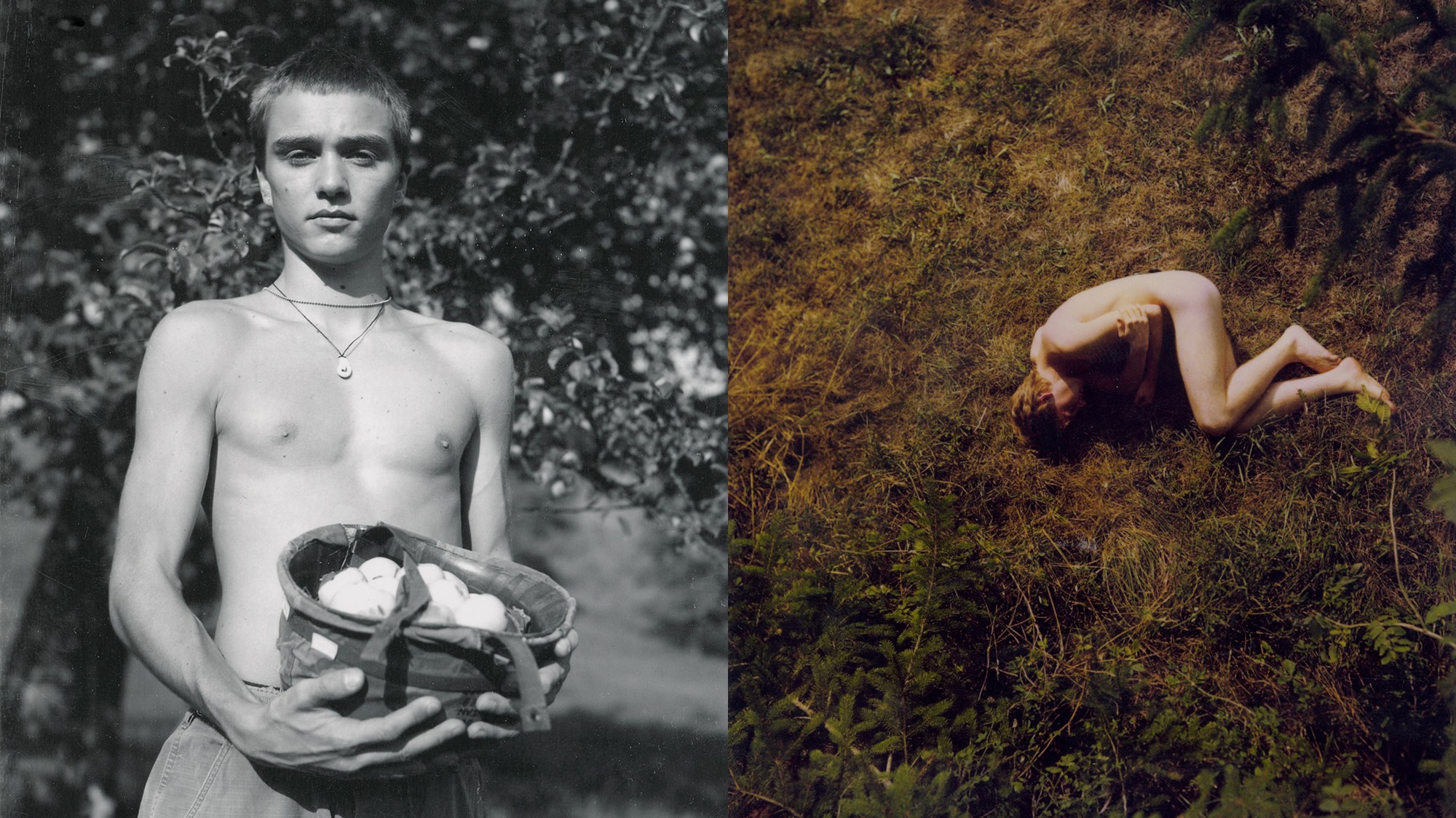

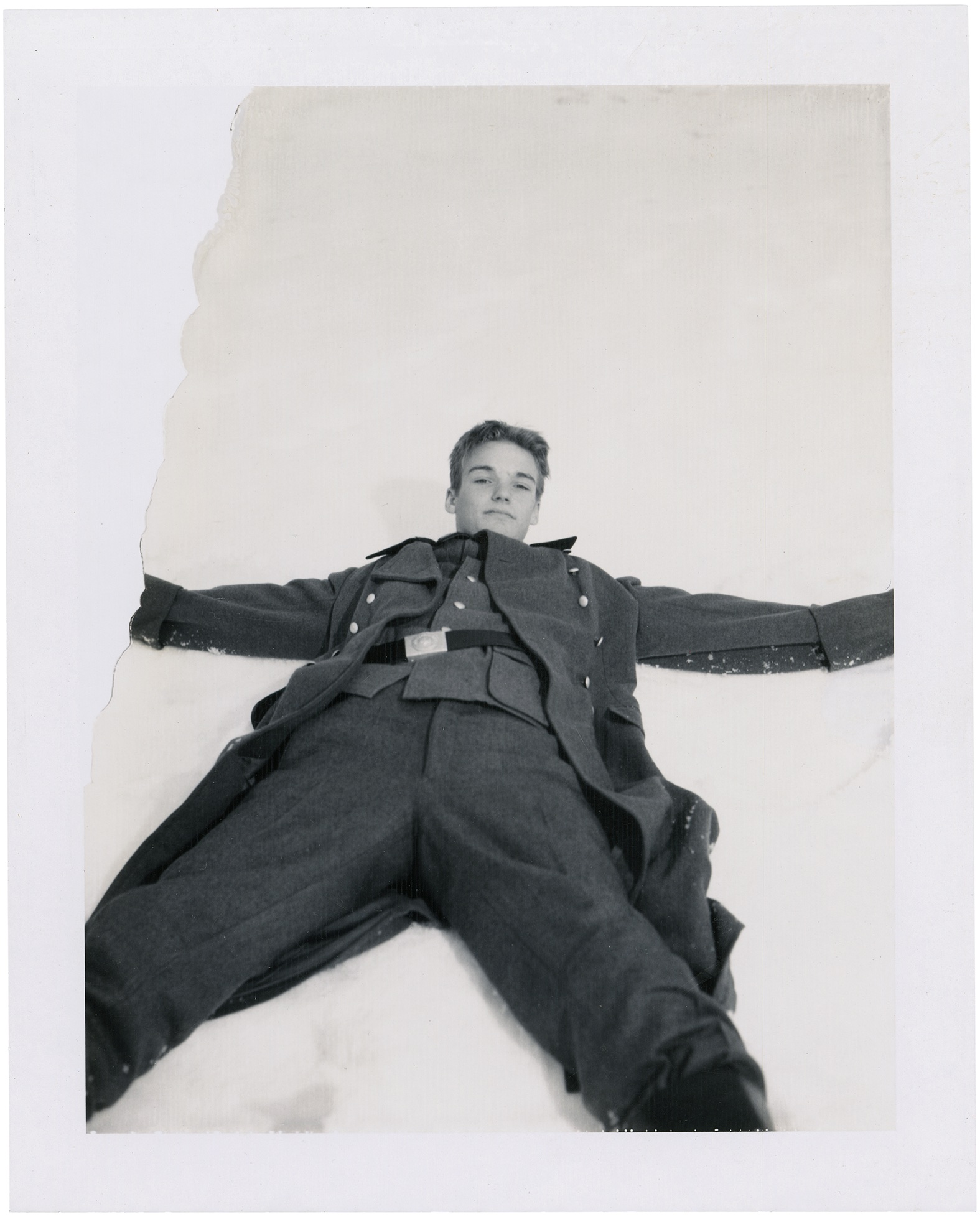

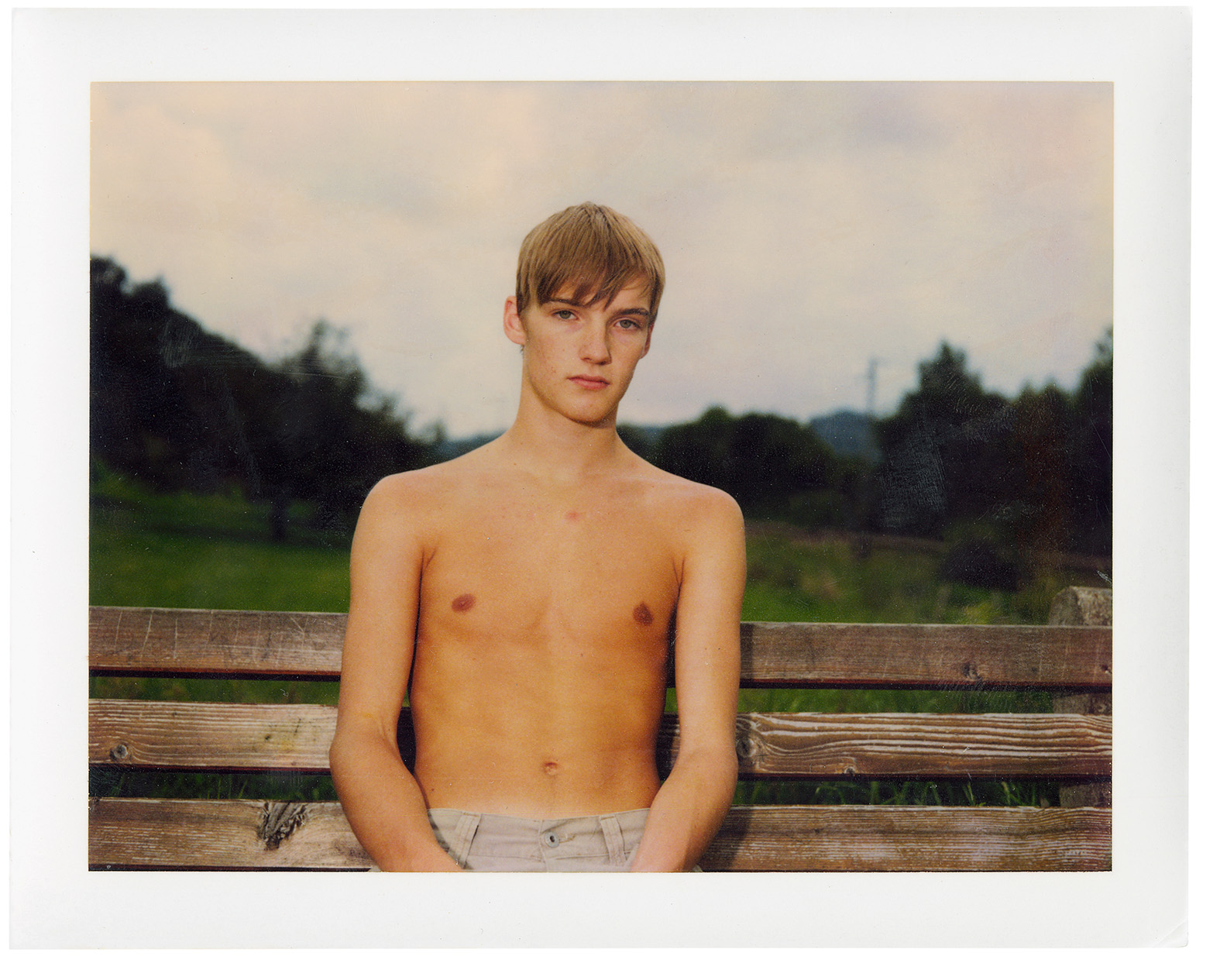

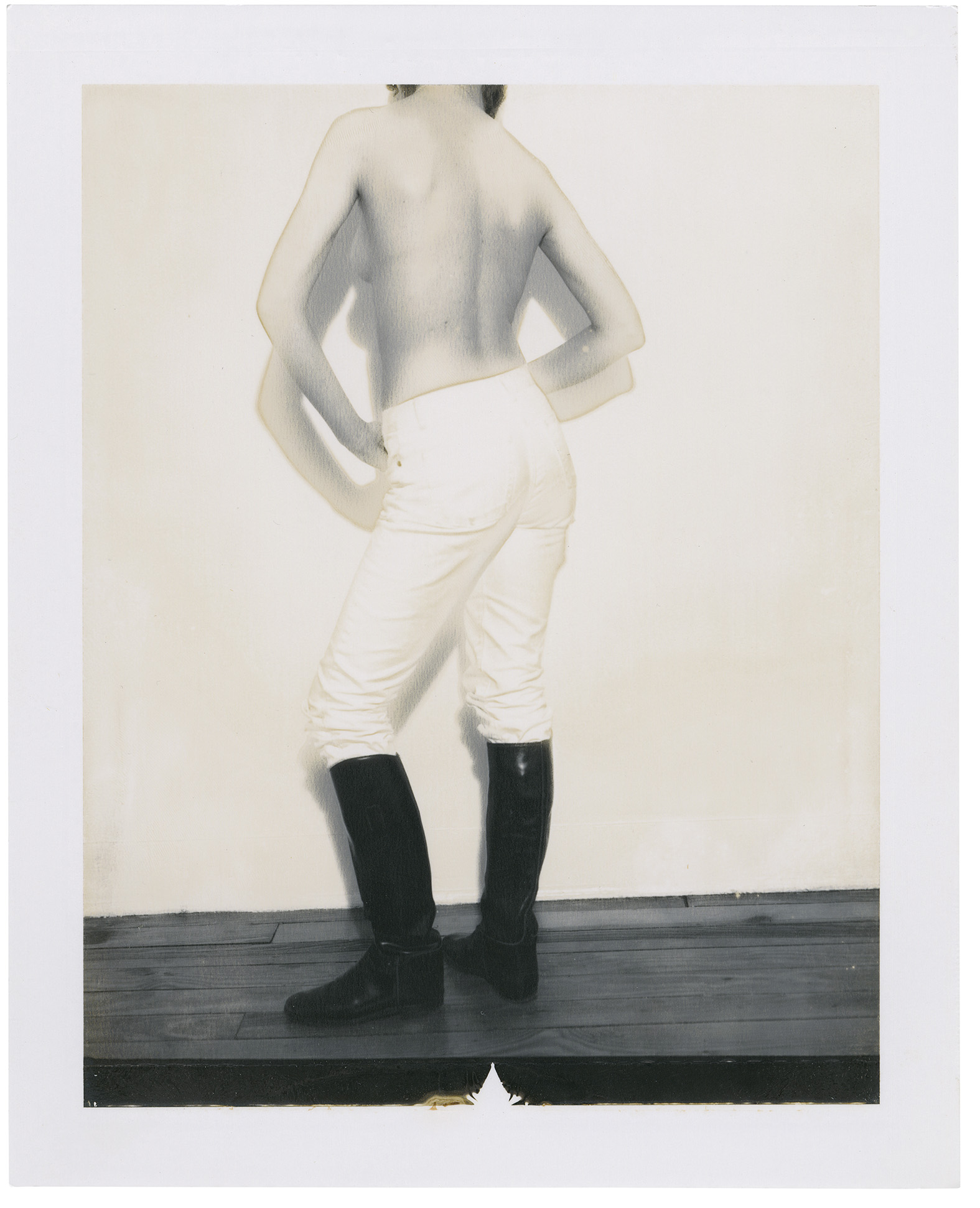

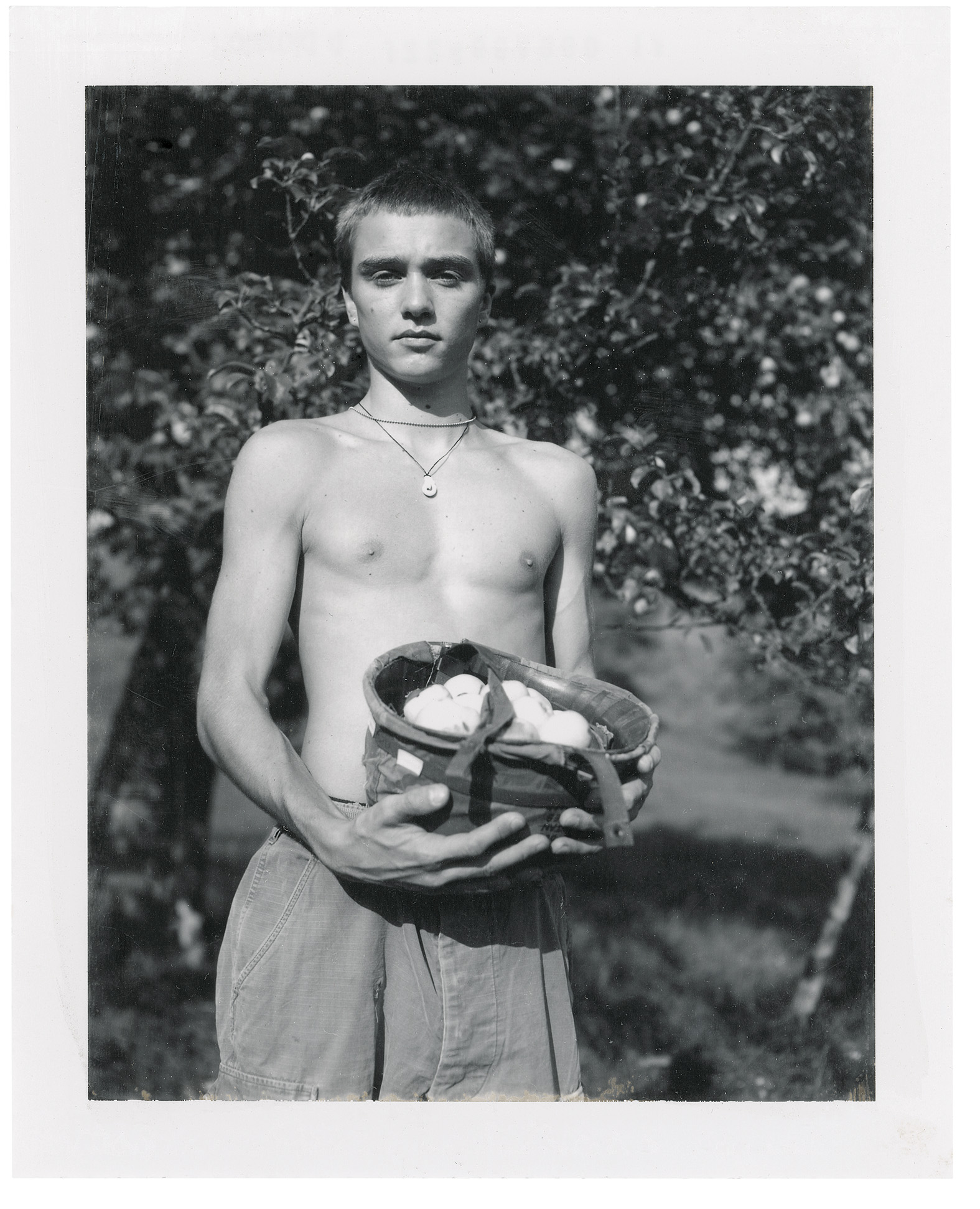

“The way of ensuring it never happens again was to act as though it never happened,” Collier says, the idea that “making it invisible will protect people against this proclivity to be destructive.” She responded by befriending young men and encouraging them to sit for her, using military clothing to resurrect the past. Her photographs show the men either shirtless or in Wehrmacht uniform, seated timidly or standing to awkward attention. Some are in their gardens, others in the woods at night, wearing full army attire under cover of darkness.

“We put on a play,” Collier explains — a historical fiction for a society starved of reflexive culture about the war. She breaches taboos but also attempts to strip them from the garments altogether, either by re-signifying the clothes (as she had observed in Greenwich Village) or creating uncanniness via exact restagings of Nazi-era portraits. “These characters don’t have a history,” Collier says. They also had no nation. Collier had to visit a NATO store to get hold of a German flag. The boys’ faces reflect the nerves of being brought into being for the first time — of embodying that which has been socially and psychologically formless.

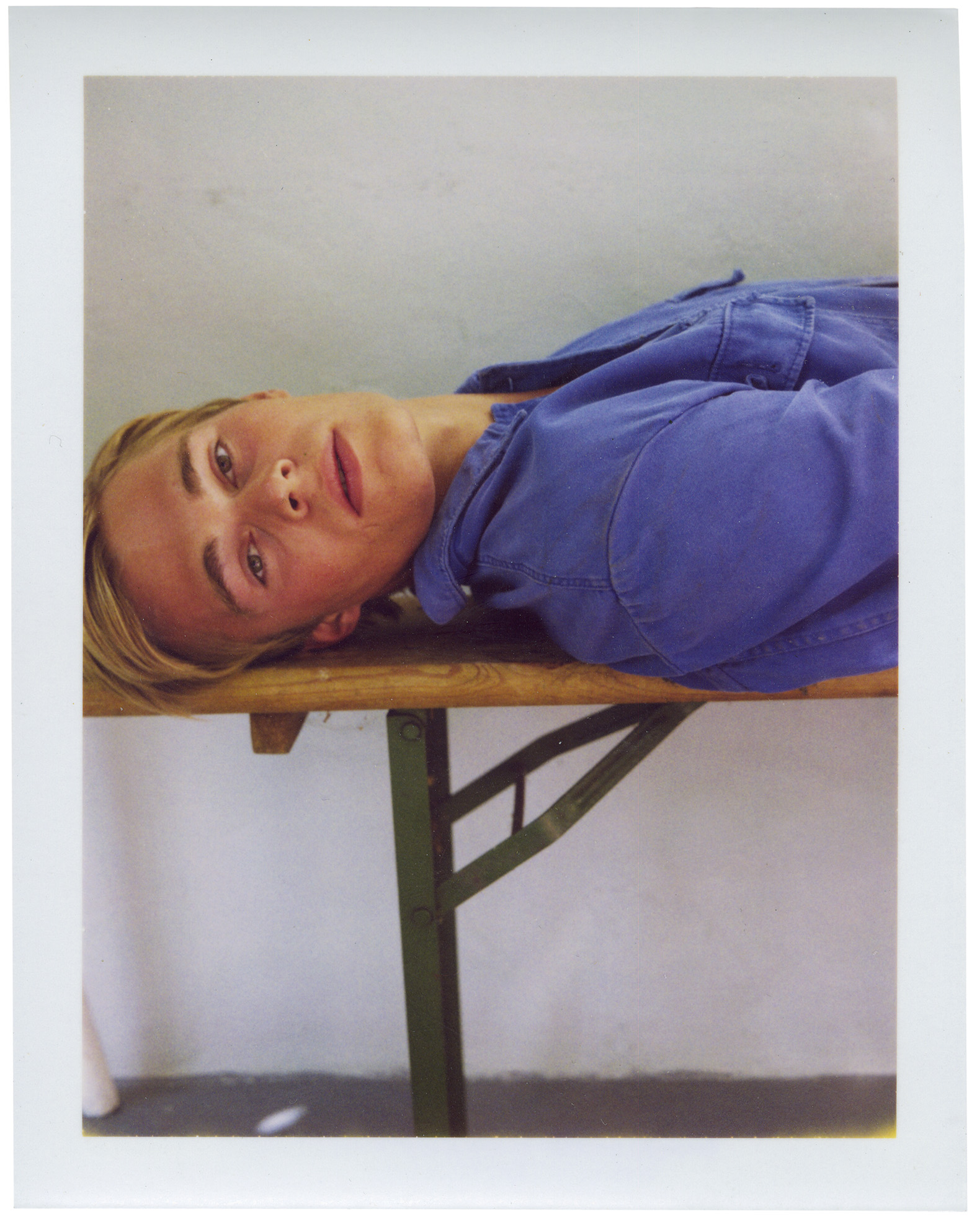

The photographs are collected in August, a new book of Polaroids made between 2001 and 2006. These are test runs captured moments before the main shots, some of which appeared in Blumen (2001) and Neighbours (2006), the first two books in Collier’s Forest and Fields series of Schwäbisch Gmünd photographs.

The Polaroids resemble behind-the-scenes shots from a costume department: dressing through trial and error, naked bodies assessed before being adorned for performance. Collier had travelled to Theaterkunst Berlin, Germany’s largest costume house, for advice on which SS uniform she needed to restage an August Sander portrait of a Hitler guard. Collier’s version features a smear of red on the boy’s lips, a nod, along with the boots and leather straps, to the underground queer and kink culture where military-wear had found a new home.

“I was trying to document the town, but to fictionalise it at the same time,” Collier says. She borrows from contemporary culture to do so, restaging a shot of Maximilian from The Night Porter, the infamous 1974 film in which a concentration camp survivor rekindles a sadomasochistic relationship with her former guard. But as much as August is characterised by subversion, Collier was determined to create a sense of authenticity — the kinds of images that German families stored out of view. In one shot, a swing set is visible in the garden behind a uniformed boy. Collier didn’t make a final photograph because of this anachronism. The Polaroids, therefore, represent an untold draft — both of a newly self-conscious German history, and Collier’s own life.

The boys are interspersed with studies of flowers, previews for what Collier calls the “still life constructions” in Blumen (2001). The second half of August also introduces motifs as Collier discovered them in the town –radios, crucifixes, stacked bookshelves — as well as boys in more relaxed, model-like poses, unburdened by the artist’s difficult questions. It is a softer end to a searching and, at times, unnerving project, giving the sense that the earlier theatrics are fleeting experiments.

There is an eternal closeness between Collier and her subjects, a sense that collective transgression has brought intimacy. She describes one boy, Jochim, refusing when she asked whether he would be photographed in Nazi uniform at a nearby circus. “He was too smart,” Collier says. However far she pushed them, social norms (and German law) were never too far off in the horizon. “There’s irony, and there’s also a lot of love,” Collier says of these relationships. “It was a cathartic dance between someone who’s linked to survival, and someone who’s linked to destruction coming together and exploring the feelings of touching taboo.”

‘August’ (2022) by Collier Schorr and published by MACK, is available to buy now.

Credits

All images courtesy of the artist and Mack