Where do those who identify as queer find cultural belonging in a political landscape that, from Donald Trump to the DUP to concentration camps in Chechnya, is increasingly and violently homophobic, sexist and transphobic. It’s an especially timely question to be asking this year in the UK — as 2017 also marks the 50th anniversary of the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality in the country. But in 2017, we also have the DUP — a rabidly conservative, bigoted and homophobic party — propping up the Tories in government.

The anniversary that’s been marked in books, TV shows, events, art exhibitions, and a renewed collective focus against conservative-homophobic social attitudes. It’s an anniversary that’s also thrown historical struggles into sharp relief, as many of those battles are still being fought. From the BBC to the Tate, this anniversary has become an urgent conversation for cultural institutions to be seen having. Curators are giving institutional space to LGBTQ+ histories and tracing their narratives into the right here and now. It’s an easy moment for these institutions to fill in the gaps in their archives and rewrite their canons to include the queer contribution to art history. They’re archiving homosexuality in order to re-materialise erased histories institutionally and publically.

In light of the anniversary, public institutions are programming their exhibitions to reflect this sensitivity. The Walker Gallery in Liverpool has made this paramount in their current exhibition Coming Out — Sexuality Identity & Gender. The exhibition marks the anniversary by assembling an archive of five decades of artistic queerness. It sources work from the Walker Gallery’s collection, and invites a range contemporary artists to contribute work; from YBAs like Sarah Lucas, to filmmakers like Steve McQueen, Derek Jarman and John Waters, to the young generation operating now (Paul Maheke, Rosie Hastings and Hannah Quinlan), Coming Out traces a more contemporary response to the same ideas put forward by the Tate in their Queer Art survey show, whose timeline ended 1967.

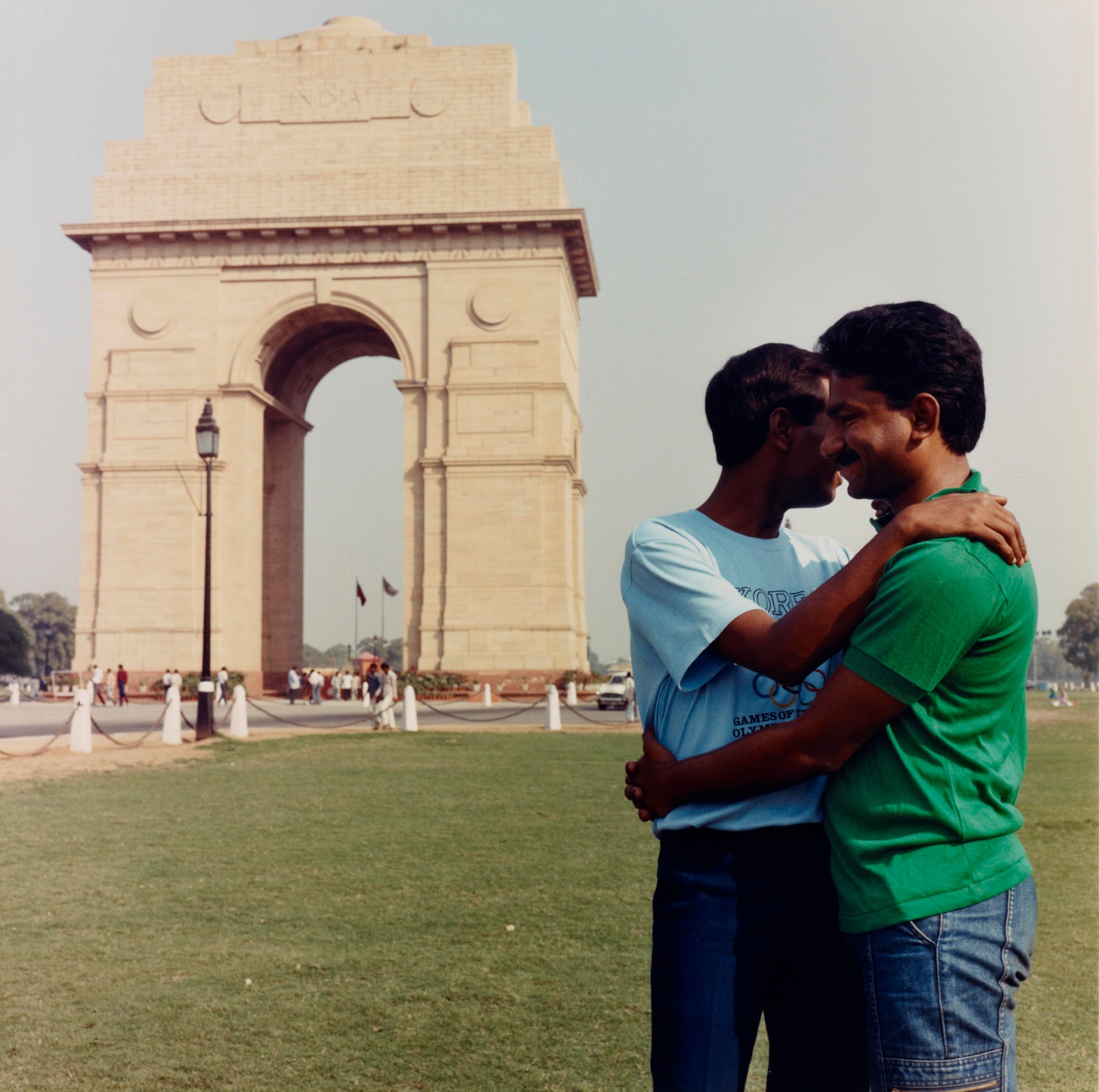

The 2016 shooting in Pulse Club in Orlando led to a number of vigils across London to mourn the victims, but also a renewed focus on the importance of the gay bar in gay culture, as a space for marginalised groups can congregate and find solidarity, and historically is an environment which has functioned as a community outlet for LGBTQ individuals. This is considered in Rosie Hastings and Hannah Quinlan’s 2016 piece, UK Gaybar Directory — the first work in the exhibition at the Walker. The six and a half hour film archives over 100 gay bars across the UK, with the intention of functioning as a public resource, bridging the gap between present and future landscapes of queerness. It’s a piece whose importance can’t be understated; the closure of gay bars has become an epidemic; in London alone, The Joiners Arms, Hoist and the Black Cap all recently closed. That just London. The loss is felt even more bitterly in the north of England, where queer spaces are even more disparate and precarious.

Queerness has often embodied a speculative cultural space: to be queer is to ‘question social norms’ as a placard states in the exhibition. The word was reclaimed in the 70s by LGBTQ+ groups to regain ownership of a term often used as an insult. The relationship to the law in relation to LGBTQ+ issues bears the demand to be consistent and responsive to perpetual social injustice.

The 2016 Public Facilities and Security Act, passed in North Carolina, saw the birth of the ‘bathroom law’, which only permits, for example, trans people to use bathrooms based on their prescribed gender at birth. Such an unprogressive and violent law surely only dehumanises individuals who identify other to their birth gender — and Coming Out is a great space of refuge and a reminder that we still live amongst extreme hostility, making it all the more important to challenge such positions.

It was only in 1999 that it became illegal to discriminate against transgender people in the workplace in the UK. The blending of historical narratives in Coming Out demonstrates how such hostility is still experienced by many in the present. For all the talk of anniversaries, legalities, and liberations, it’s important to keep an eye on the current problems.

A 16 minute installation I Want by Pauline Boudry and Renate Lorenz features a performance by Sharon Hayes, reciting fragments of Kathy Acker’s writing alongside quotes from Chelsea Manning. The military is institutionally violent against those who identify as transgender; the piece contemplates how the assertion of oneself as transgender can function as a form of direct action and resistance against such oppressive structures. Trump’s recent transgender military ban has constructed a space of precarity for those who identify as transgender, making artworks such as I Want particularly timely. Even more so with Manning’s release from prison this year, having had her sentence commuted by Obama.

The film asks: what does it mean to be transgender in constraining situations, such as prison? It dwells in a post-identity space; the blending of two individuals and the fact it was filmed in one take with two cameras, reflects the dual identity of Manning and Acker found in Hayes’ monologue. This intertwining of selves seems to open a new trajectory of being and seeing, where different ideas of storytelling and oral histories can act as a form of direct action.

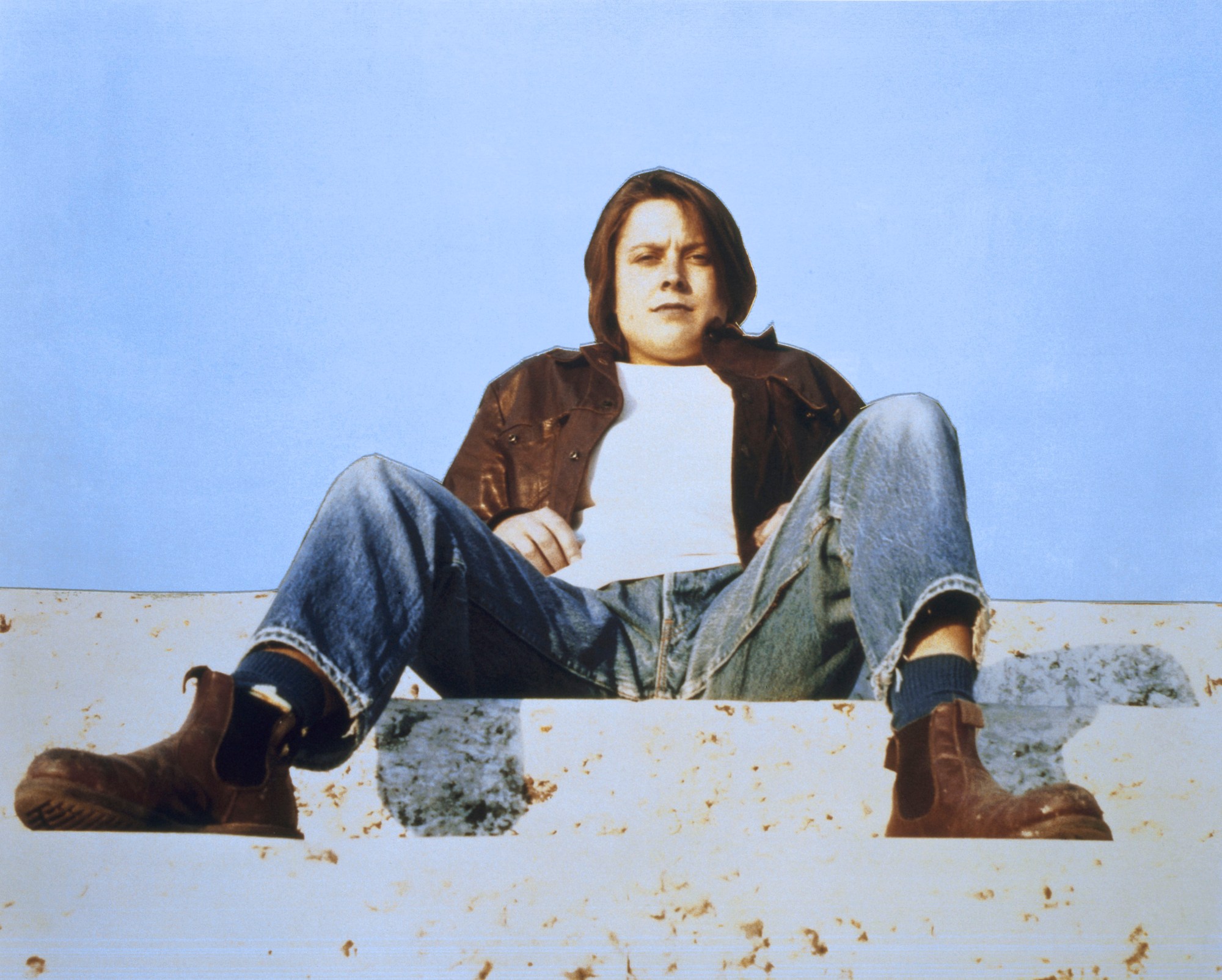

Surely then it is not just the historicising of legislation, but also the urgency for collective reflection that makes Coming Out so timely and historically poignant. Derek Jarman’s Morphine is a reminder of the AIDs crisis, the erasure of homosexual men, and their scapegoating in the tabloid press — a theme throughout the exhibition. Desire is explored in Steve McQueen’s 1993 film Bear, which depicts him wrestling naked with another man meditating upon the slippage between the erotic through subjects of the film.

But how should we re-imagine these histories, when revisited in this artistic context? Much like its subject matter and the marginalised communities it references, Coming Out is transformative in its approach, challenging how curators employ institutions, rewriting previous narratives, giving recognition to what maybe lost historically.

What makes for this condition? Between 2005 and 2016 there was a 73% rise on individuals demanding HIV care in the UK through the NHS. John Waters’ Alien Sex Club mimics the spatiality of saunas and gay bars, where visitors are taken through a brightly coloured neon installation including films, paintings and performances. These mark the enclosed space, and visitors are invited to have their tarot read by a character called Barbara Truvada. The tarot cards serve a dual purpose— on the one hand it allows us to imagine a new identity and sense of purpose. On the other, the cards hold a greater historical narrative, in the attempt to create a new visual language narrative to reimagine HIV and the rise of people placing demands on NHS services in the last decade. As the exhibition ends with Alien Sex Club, as visitors we are reminded the precarity of healthcare, particularly as the NHS begins to limit trials for PrEP this year.

Disengagement is not too dissimilar to apathy, and apathy can be a byproduct of inattentiveness. Coming Out’s agenda is an active response against the erasing of these communities and current government’s austerity cuts. 1972 saw the first Gay Pride rally in London, where over seven hundred people attended. Such a statistic bears weight on how far these histories have developed societally and the importance of solidarity. The Walker’s gallery exhibition is one example of such solidarity, for its acute attention to how we must continue to critique and question the representation of queerness. The exhibition demonstrate how gesture becomes event. This resurgence of the past and current climate demands collaborative and collective circumstances in order to reimagine different sectors of society, through institutions, art and conversation, alongside celebrating the diversity of art derived from alternative LGBTQ+ histories, as a queer alliance and form of kinship.