Named “the greatest threat to the internal security of the United States,” by FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, the Black Panther Party for Self Defense (BPP) stood at the vanguard of the Civil Rights Movement in the United States, heralding the arrival of Black Power in word and deed alike. In the wake of the assassination of Malcolm X and the Watts Uprising, two young college students — Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton — came together in Oakland, California, to found the BPP in October 1966.

Subscribe to i-D NEWSFLASH. A weekly newsletter delivered to your inbox on Fridays.

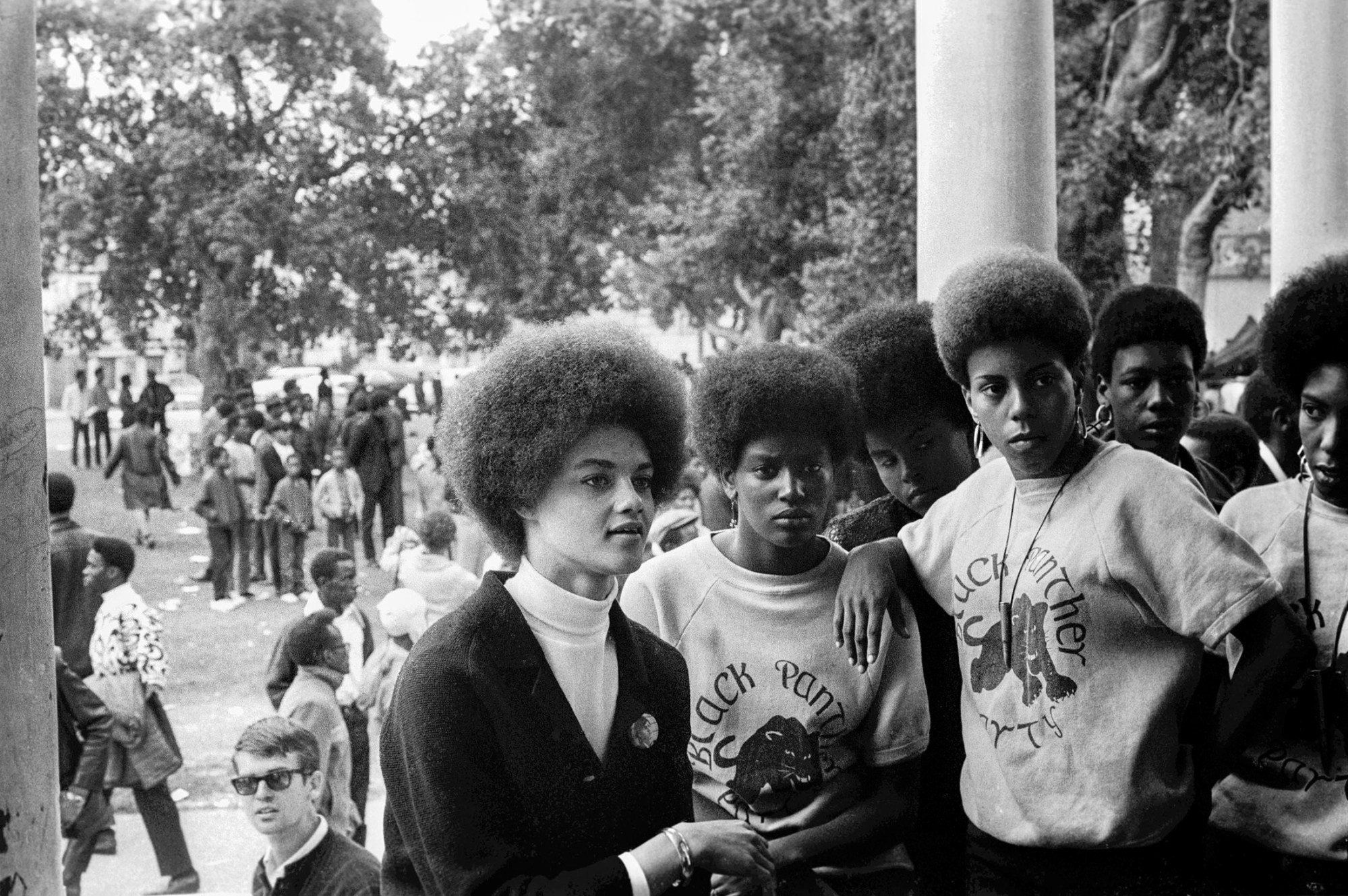

Donning blue shirts, black pants, black leather jackets, and black berets, the Black Panthers openly armed themselves under the protection of the Second Amendment, patrolling the streets of Oakland to protect the people from the deadly spectre of police brutality. Bobby explained, “Our position was: If you don’t attack us, there won’t be any violence; if you bring violence to us, we will defend ourselves.” The guns established the Panthers as a militant force that would not be cowed by threat or abuse — but they were just the first line of defence against injustice.

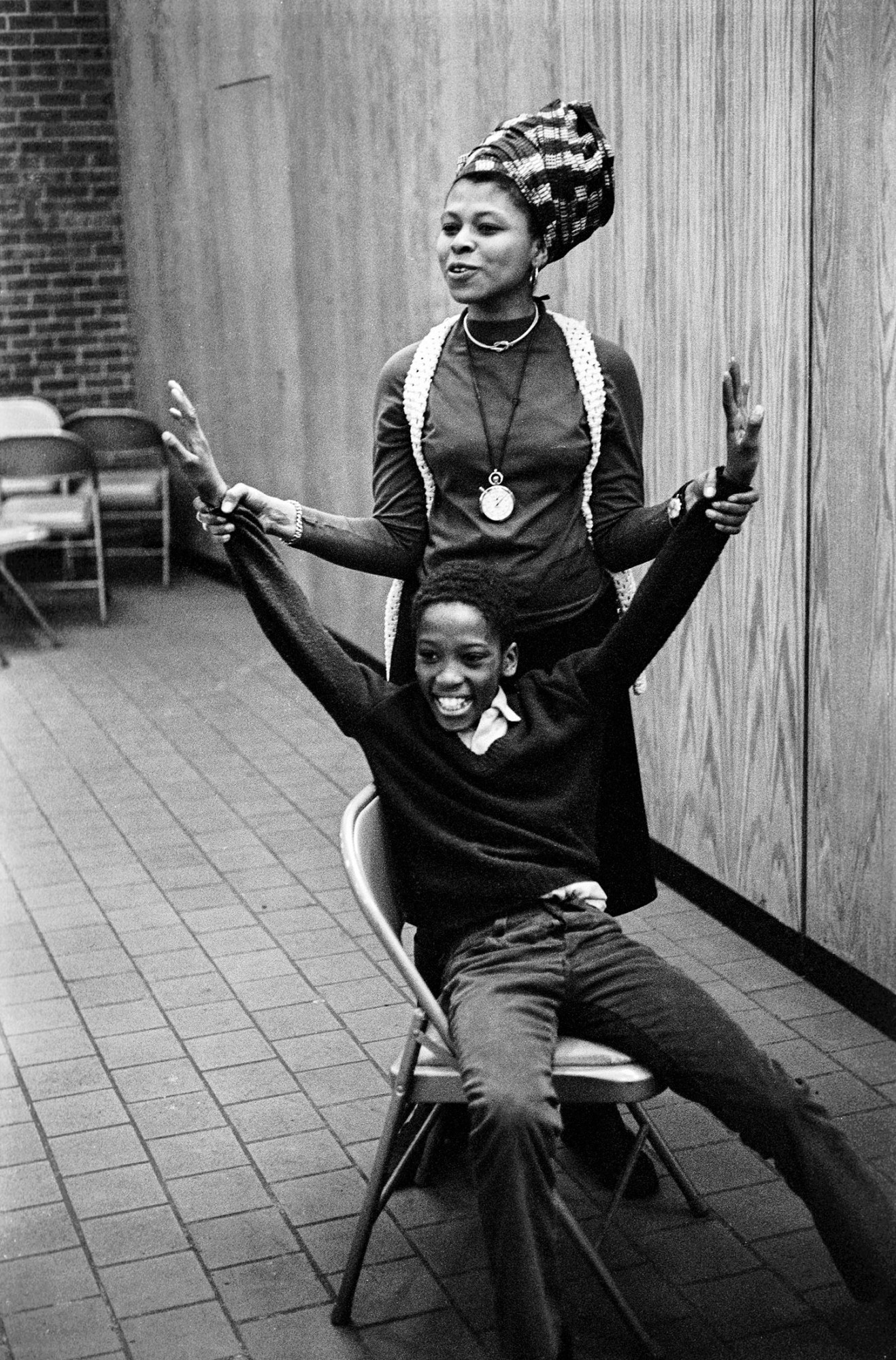

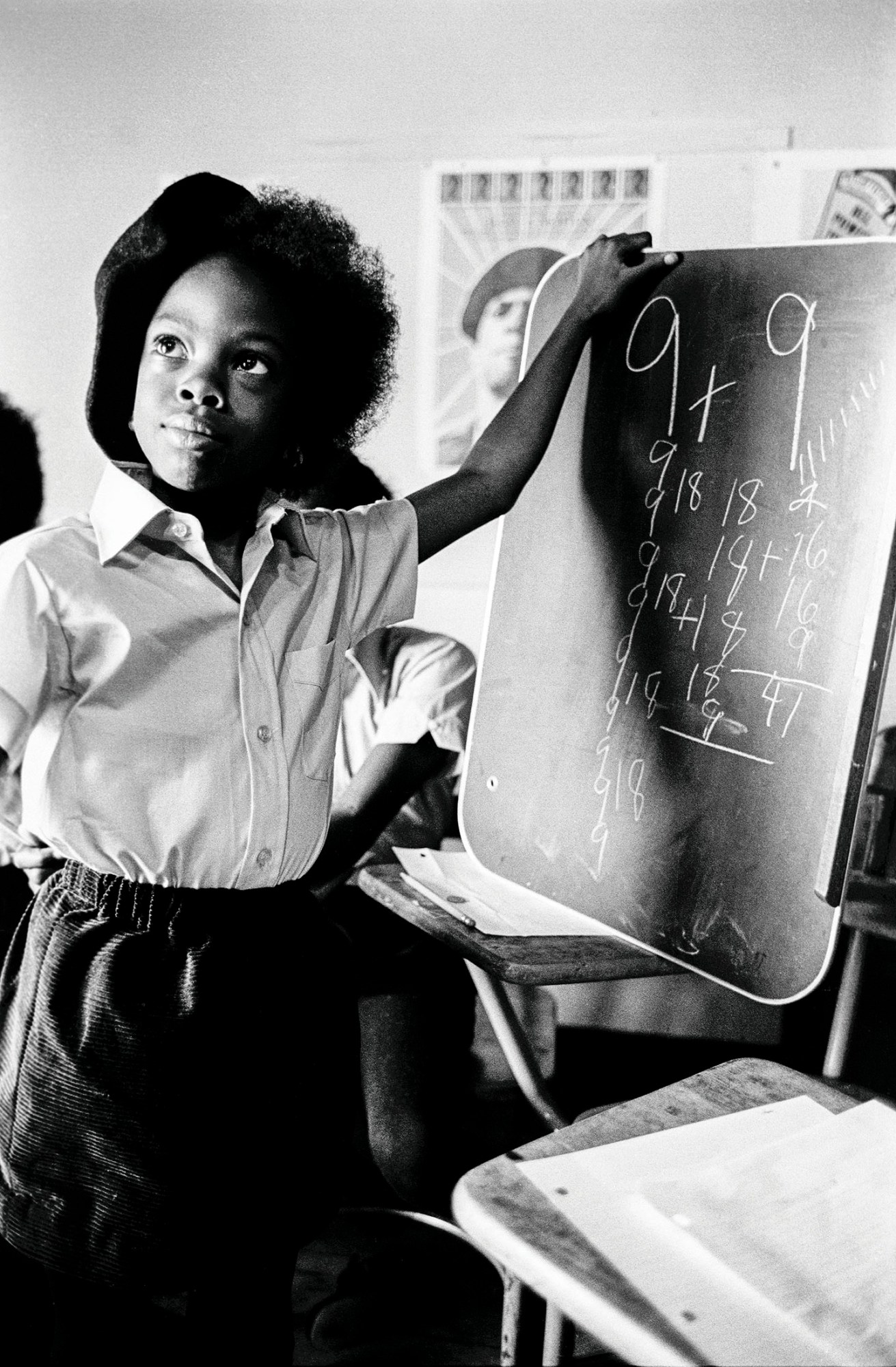

The BPP developed a Ten Point Platform and Program to create political, economic, and social equality. Calling for full employment, reparations, housing, education, military exemption, end to police brutality and murder, freedom for the incarcerated, Constitution rights during trial, and self-determination, the BPP established local chapters in 68 cities in 40 states — and instituted over 60 community survival programs like the Free Medical Clinic, Free Breakfast for School Children, Free Food, Clothing, and Legal Aid programs to protect the most vulnerable in just five years.

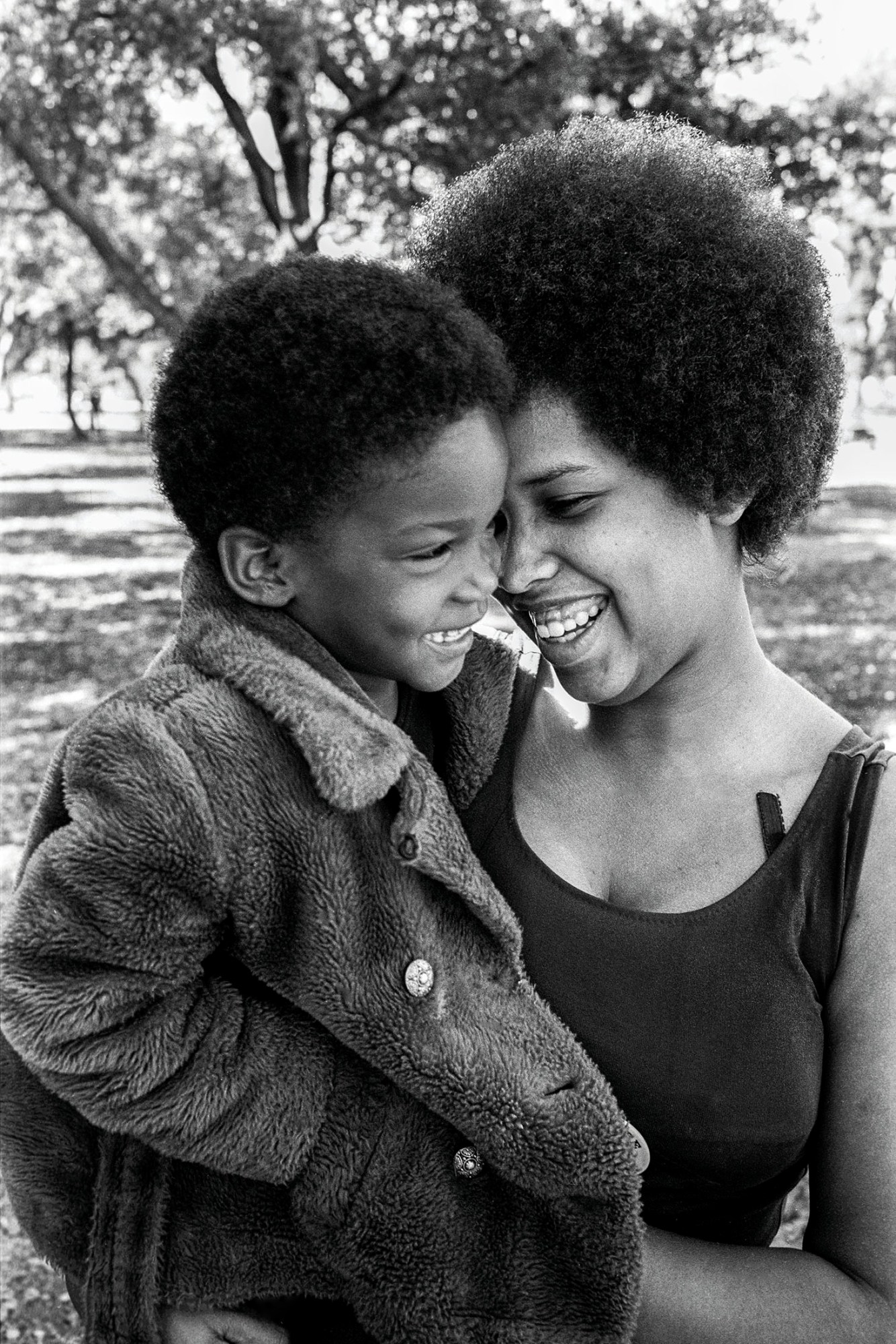

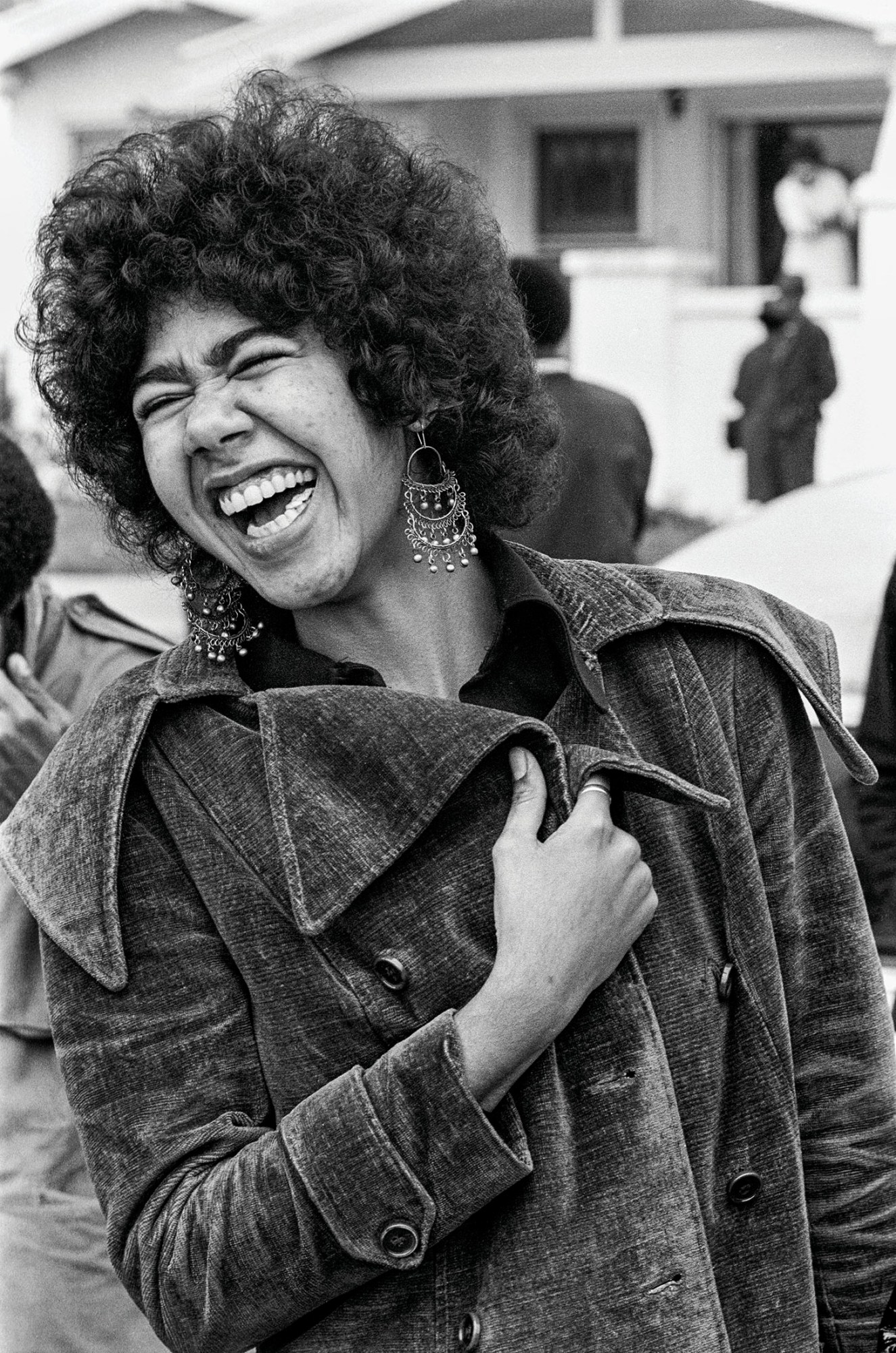

Although luminaries like Angela Davis, Kathleen Cleaver, Elaine Brown, Ericka Huggins, and Assata Shakur played integral roles in the BPP, the role of women has largely been overlooked. In the new book, Comrade Sisters: Women of the Black Panther Party (ACC Art Books), and an online exhibition, Ericka Huggins and photographer Stephen Shames, joined forces to set the record straight and honour the contributions of women from all walks of life who came together to participate in a movement for freedom that had an immediate impact of the material conditions for Black Americans nationwide.

Although the media and government were largely focused on the men, women have played an integral role in the BPP, accounting for at least 66% of the membership. “Women were literally the heart of this new political approach to Black freedom,” activist and educator Angela Davis writes in the book’s introduction. “The leadership offered by women of the Black Panther Party was down-to-earth and profoundly collective. This was leadership designed to serve the people, ensure their survival, and, ultimately, to transform social institutions by prefiguring what life might be like if people of all racial, religious, and class backgrounds could claim substantive access to education, healthcare, and nutrition.”

Comrade Sisters pairs Stephen’s intimate, incisive, and inspiring portraits and documentary photographs with testimonies from many surviving members and their kin. Woven together, the images and stories form a vast tapestry of the BPP’s impact on individual and collective lives, while also offering a blueprint for creating change from the ground up. Recognising there had to be “a way out of no way,” the women of the BPP set to work on programs to provide “land, bread, housing, clothing, justice, and peace” to the people. Motivated by love, they provided for those in need and in doing so gave the Panthers credibility. “All power to all the people” wasn’t just a slogan; it was a fact, one that could be seen through these acts.

At its core, the BPP drew upon the tenets of communism and showed that such a system could work to support the Black and poor. Hoover used the full power of his position to wage war. By 1969, the BPP was the primary target of COINTELPRO, an illegal operation to destabilise, discredit, and criminalise the Party through surveillance, infiltration, perjury, police harassment, assault, and ultimately, murder. His tactics proved successful; although the BPP would formally end in 1982, by the early 1970s it had largely disbanded. Yet its legacy continues to reverberate across generations. Part of that is due to the Panthers’ mastery of media and its ability to control the narrative through both image and text.

Stephen first met Bobby Seale and Huey Newton in April 1967, before he even had a photography career. Just 20 years old, the Berkeley student had just gotten a camera and brought it along on the very first peace march against the Vietnam War in San Francisco. Stephen remembers walking along and seeing two very charismatic Black men at a table selling Red Books. He raised his camera to take a photograph of Huey — then someone stepped in front just as the shutter snapped. “It was one of my first rolls of film, and I shot one frame,” Stephen recalls. “I didn’t take another.”

The inauspicious start proved to be anything but. Stephen began recording incidents of police brutality on Telegraph Avenue, and soon thereafter became a staff photographer for the Berkeley Barb and a stringer for the Associated Press, New York Times, and Newsweek. Although he’s not exactly sure when he began working with the BPP, by 1968 Stephen was in the swing of things. “The Panthers understood the value of photography and the visual image,” Stephen says. “I learned from Bobby how they created an image, not just through pictures and videos but also the uniforms. They would line up at rallies and were disciplined. They exuded pride.

“The Panthers had a newspaper and worked with filmmakers, but it wasn’t just about media, it was about being politically and socially active. They were embedded in the community and registered thousands of people to vote. They recognised how important it was to control not just national but also local offices, and ran candidates with the Peace and Freedom Party as early as 1968. They understood the need to make coalitions and even to compromise. I learned from the Panthers how to be effective and put the pictures to decent use.”

It is a position Stephen maintains to this day. With Comrade Sisters, his third book on the Black Panthers, he honours the women whose contributions are finally receiving their proper due. “The men didn’t always treat the women [with respect],” Stephen says. “Bobby had to confront some of the men about their attitudes, and the women also confronted them. They also brought women’s issues to the movement and, because of them, the Panthers were the most progressive organisation of the time.”

Unlike many other radical groups of the era, women held positions of leadership. Kathleen Cleaver, Communications Secretary, was the first woman in power at the Party, was soon followed by Elaine Brown, Chair of the BPP, and Ericka Huggins, Director of the renowned Oakland Community School. Artist Tarika Lewis, was the first woman to join the BPP at age 16. Her work was featured the earliest issues of The Black Panther newspaper, showing men and women alike as revolutionaries.

“The Panthers had intelligent, powerful women out front and centre,” Stephen says. “They could stand their own against anybody. Kathleen was a keynote speaker at rallies; she was equal with all the men and everybody knew it. Women weren’t tokens or window dressing. It was important to have role models out there doing real work and inspiring young people.”

‘Comrade Sisters: Women of the Black Panther Party’ is out now on ACC Art Books

Credits

All images © 2022, Stephen Shames