It’s now exactly 100 years since Marcel Duchamp signed a urinal R.Mutt, called it Fountain, and submitted it as a work of art to the first exhibition of The Society of Independent Artists. Dropped into 1917 New York, Fountain caused a minor scandal in the avant-garde art world at the time, but it’s had a major reverberation throughout wider culture in the century since.

The original Fountain was lost, thrown out by Alfred Steiglitz, after he took the now famous photo of it for Dada magazine The Blind Man. Then in the 50s and 60s, Duchamp commissioned a series of reproductions of the original fountain, remaking the readymade as it were, and peddling them to all your favourite major art collections around the world.

There’s some sort of avant-garde art world fable in this remade readymade going full circle, from scandal to thrown out in the trash to lost amongst the accumulated trash of all those other major groundbreaking artworks. Shocking to boring. OMG to Zzzzzz.

So what to make of the readymade now? If Duchamp’s Fountain feels a little passe in 2017, it’s because everyone’s rushed into the chasm he opened up and made their homes in it. What was once lush expanses of fertile green land, untouched and Edenic, is now overdeveloped. Duchamp, we could chance our arm to say, invented modern art. And maybe we’re still worryingly in thrall to him.

So for all the words we could wasted on rolling through Fountain’s impact, influence and reaction against it let’s leave it by basically saying his new ideas gave us everything from conceptual art in 60s to the outbreak of zombie formalists spraying down canvases with fire extinguishers filled with paint in 2010s. Nowhere is safe or free or immune from the pissy rupture Duchamp proposed with Fountain – even those new gen of post-post-internet crafty kids, putting their actual hands to actual materials are going through a quiet rebellion against the masculinist bravado of “It’s art cos I’m an artist”.

Which rather circuitously brings us round to Double Take, an exhibition just opened at Skarstedt’s still new-ish London space. Double Take explores the ideas and ideals of appropriation in the world of photography, from Collier Schorr to Barbara Kruger to Richard Prince, Or, just another strand of Duchamp’s influence if you like, i.e., the photographic readymade.

And the photographic readymade, at the generation who pioneered it, is having a bit of a moment right now. In NYC, at Whitney and MoMA, you can see Fast Forward: Painting from the 1980s and Louise Lawler’s Why Pictures Now, both of which explore a similar time in photographic artistic development. In London, The Zabludowicz Collection and Luxembourg & Dayan gallery explore fiction and collage in photography, respectively. Together, all four exhibitions, and Double Take at Skarstedt, present a thrillingly timely relook into the era, and its relevance today in the photo-saturated world we blink our way through. The power of image, as a concept, idea, ideal, and from adworld to artworld, has seeped into our everyday lives like never before. Everything is ruthlessly reblogged, liveblogged, memed, uploaded, and downloaded. The kind of photo-dystopia the generation of practitioners examined, has only blown up in the intervening years.

To mercilessly adapt an old adage; you could say something like “good artists copy, great artists steal, modern artists appropriate” – which is to say that stealing, signing a fake name on an urinal, has lost its power of modernity; the shock of the theft is no longer enough. Too simple an act, and an act too overdone. Appropriation is the name of the game now. Art is just a copy and paste away. Each photographic appropriation, at its best anyway, is a radar beep into the darkness, producing an outline of the Insta-world we scroll through on our lunch breaks.

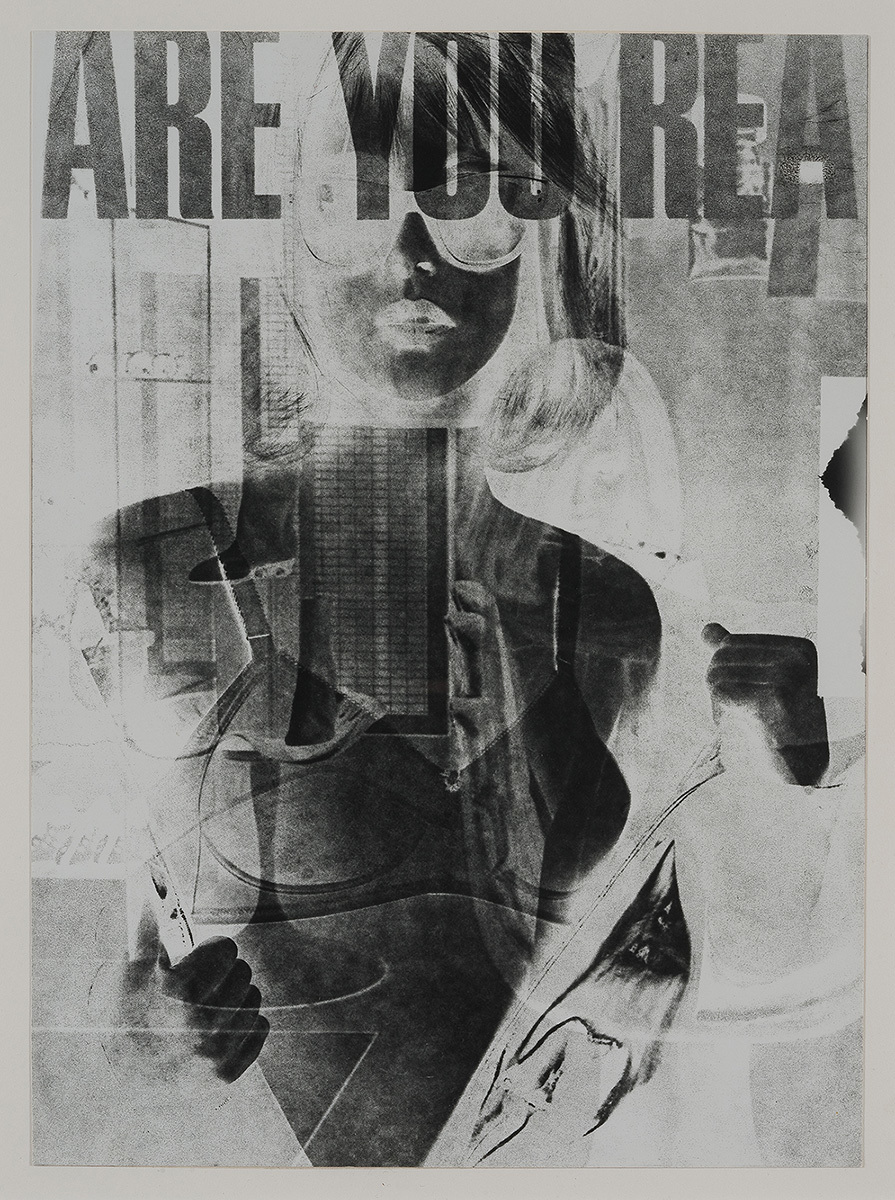

The Pictures Generation, who arose in the late 70s, in New York, were the first on the appropriation scene. Their work was a direct response to the flat stimulation of the commercial world and to the blunt burgeoning way it played with our simplest desires as mercantile strategy; nostalgia, longing, love, sex, greed, wanderlust, indulgence, beauty, chauvinism. A rogues gallery of modern sin rendered in shallow imagery. There’s a narrative wholeness in the appropriation of the visual instant archaeology offered up by their work, a turning of documentary into fiction. In a world of impenetrable advertising saturation, the solution of the artists was to merely present and represent it back to the world. If Duchamp’s Fountain was a readymade comment on the artworld (he’s taking the piss) then the Pictures Generation (named for one of their early exhibitions, titled Pictures, at Artist’s Space in New York) were offering readymade comment on the wider world.

So the exhibition at Skarstedt, Double Take, assembles the best of those strategies and comments. Collier Schorr, Richard Prince, Anne Collier, Roe Ethridge, Barbara Kruger, Louise Lawler, Hank Willis Thomas. The exhibition, historic is scope, but prescient in outlook.

One thing we can’t avoid is Richard Prince, who obviously draws a fair amount of flack no matter what he aims his camera at. But for all the sound and fury directed at Prince, for either cack handed attempts at relevance, trolling attempts at politics, or perceived historic indiscretions, his work still bears testament to the time we live in. Especially all the bad things about the time we live in.

My first exposure to Richard Prince came at a press viewing for the Tate Modern’s 09 exhibition, Pop World. In a red room, tucked away from the main exhibits (Warhols and Hirsts and Harings) in a boudoir-red room, liberally splashed with trigger warnings and content notices, was Spiritual America. A rephotographing Prince made of a naked, preteen Brooke Shields, decorated in a horrifically OTT tacky gold frame. Her eyes staring out of the photograph into our souls. Is the work accusatory or predatory? In that dichotomy rests the power of the Prince’s appropriation. Spiritual America might lay claim to being the Moby Dick of the Pictures Generation; or rather, the great American reappropriation photograph. Hoisting up American society by it’s own petard, a lurid, disgusting, fleshy display that cries out “this is out what you are.” The Met Police were called. The image was taken down. It was replaced by a different picture of Brooke Shields.

Prince’s oeuvre lays claim to best represent America to world; it’s all there. Transcendent and tacky, exploitative and explosive, a little misogynistic and a little magnificent too. Marlboro men and exploited pre-teens. That’s America. The act of rephotographing is essential to it, because in selecting this images, these readymade symbols and icons, Prince is merely reflecting, presenting and showing. The readymade creates a space that shifts all the morality onto the viewer, and that often makes the viewer uncomfortable. Not least when his work treads a fine line of between reappropriation and straight up appropriation.

We believe in the power of the images we see, but we believe in the power of the images we create even more, which is why Prince pisses so many people off. No one likes to have themselves turned from living, breathing, hoping, dreaming three dimensional person in flat symbol of Some Greater Thing. We are all beautiful individuals with totally unique Instagram profiles, just like thousands and thousands of others.

In the catalogue, Richard Prince writes of a time when Collier Schorr was subletting his NYC apartment: “She would talk to me about living with Spiritual America… how it was the perfect image for her to live with at that time… that it became for her a kind of religious icon or something otherworldly, an image that was hard to define because of its man-boy-women-girl beauty.”

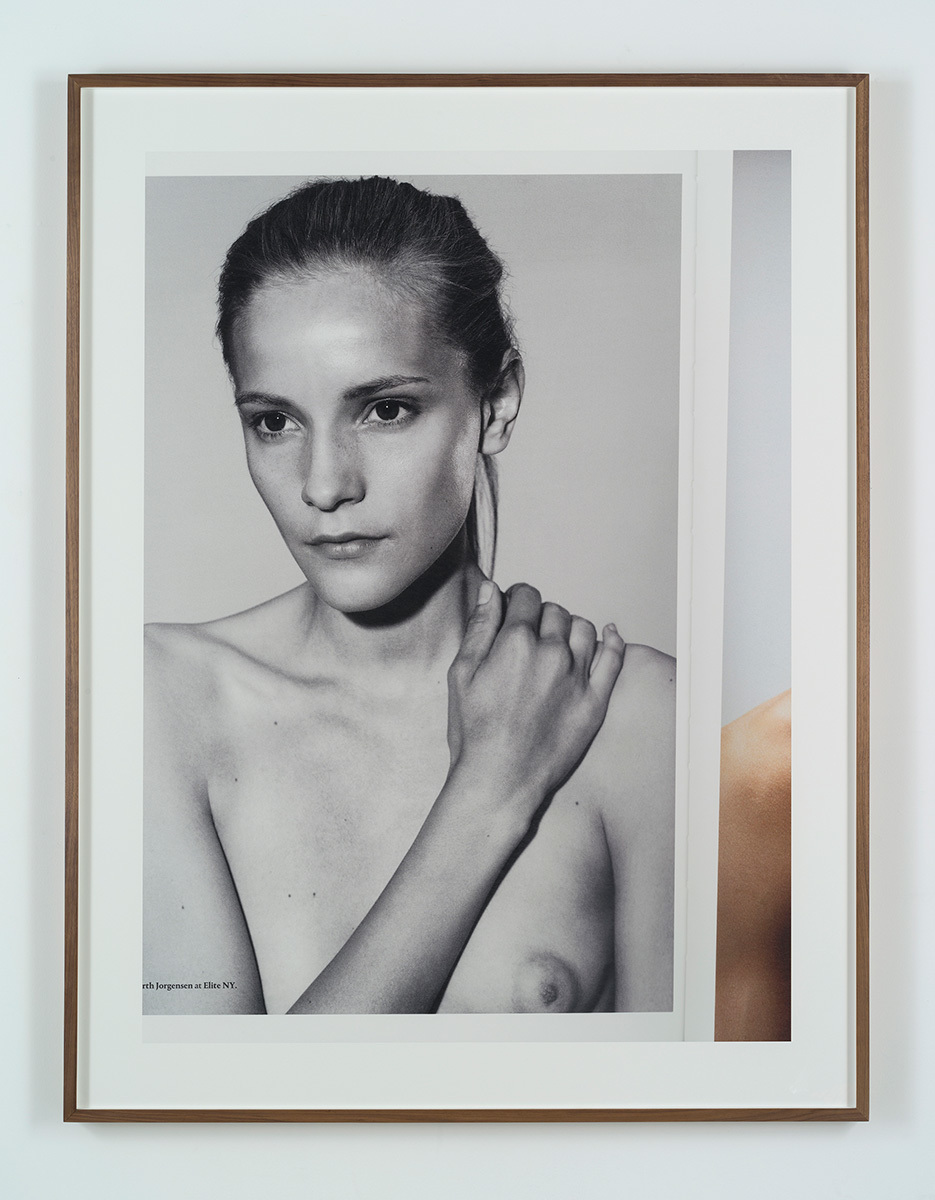

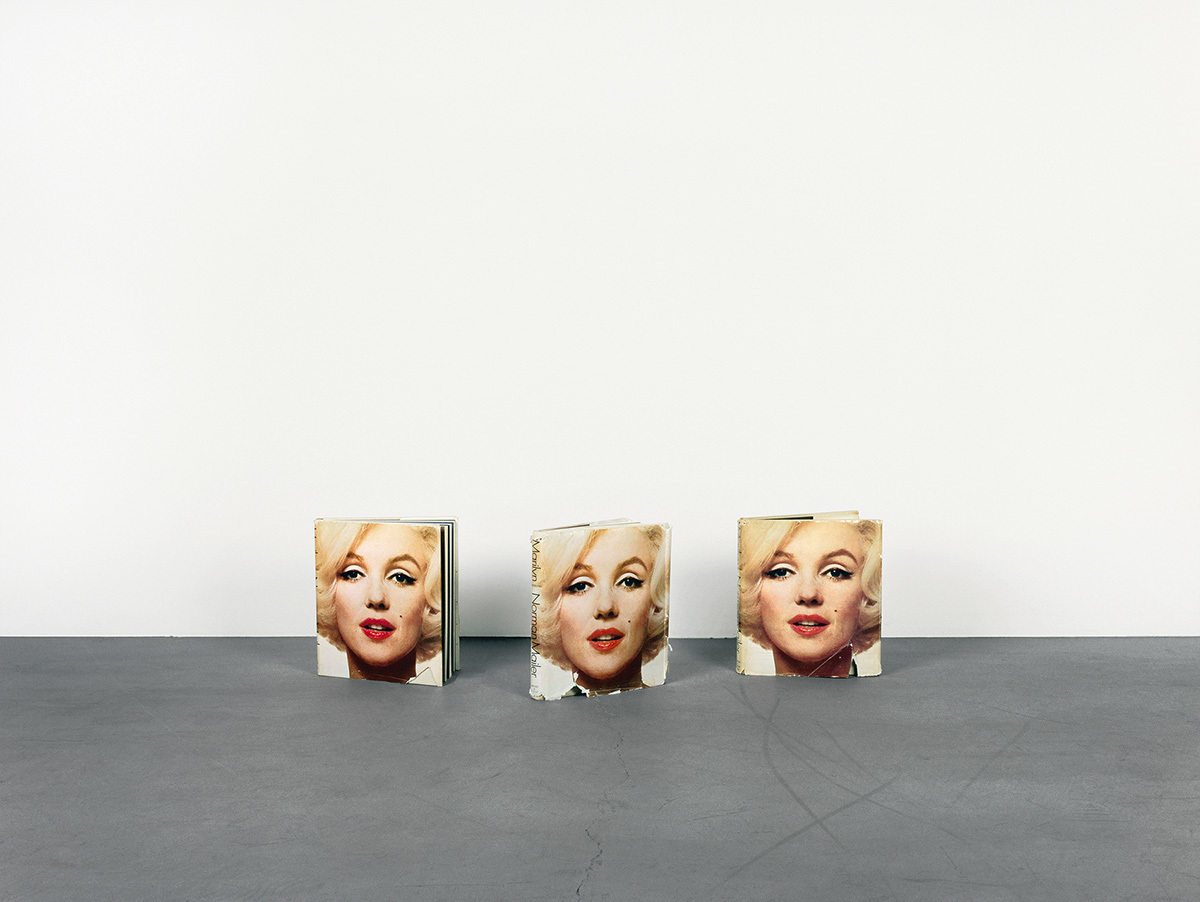

Collier and Prince form an uneasy artistic duo. What they do, how they do it, and why they do it, is so different, yet overlaps in unexpected places and in unexpected ways. For a start, Collier’s practice is more varied, more obviously politically engaged, and a fair chunk of her practice is not what we would really describe as a conventional art practice, in that it contains fashion editorial work, advertising work, various commercial work. Yet there is a subtleness to Collier’s photography, a gentleness and lightness with its questioning, an emotional complexity that belies the formal simplicity. (Although surely we’re all bored to death of hierarchically categorising what makes up “art” – right?) Not explicitly a member of the Pictures Generation either, Collier, though, follows through on their promise. In her gallery shows she reuses her own photographs, often collaged and rephotographed, or presented as found work; recrafting her non-artwork works and reusing them as the raw materials for her practice.

In fact Collier’s work is maybe more indicative of the subtlety and variety of proposals put forward of the movement than someone like Richard Prince, despite the fact that he stands above the rest of the generation of artists, in terms of fame at least, as its troll princeling.

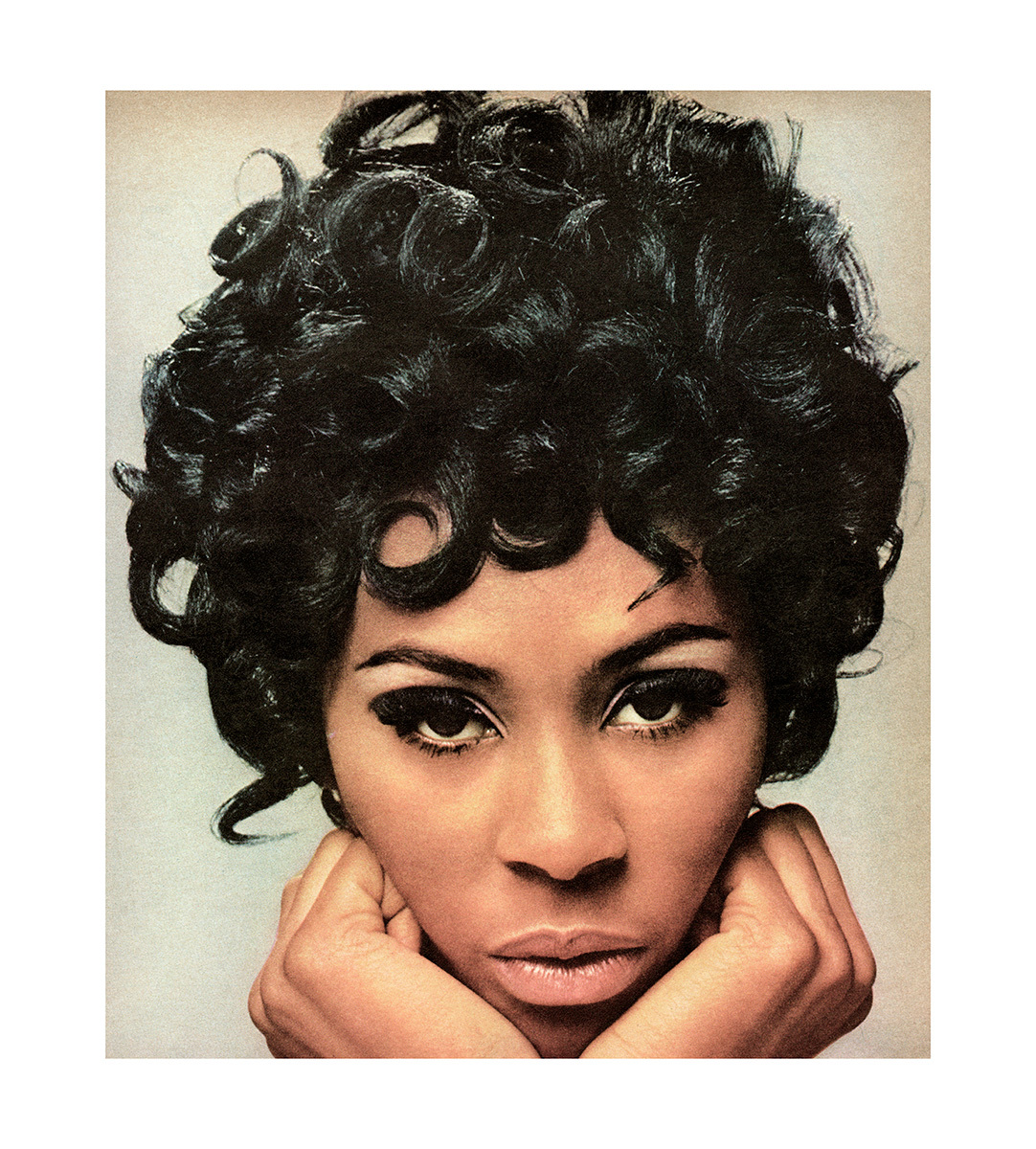

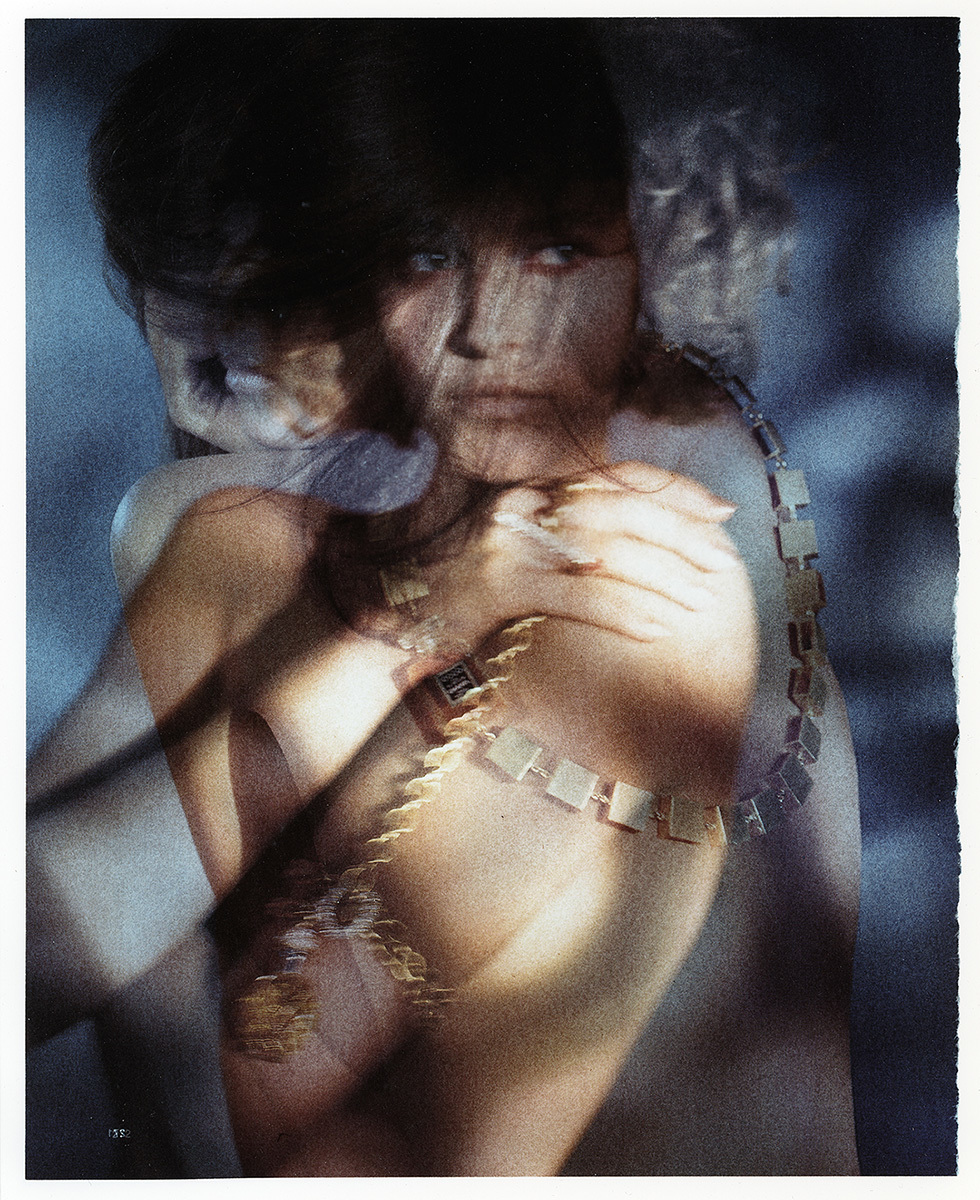

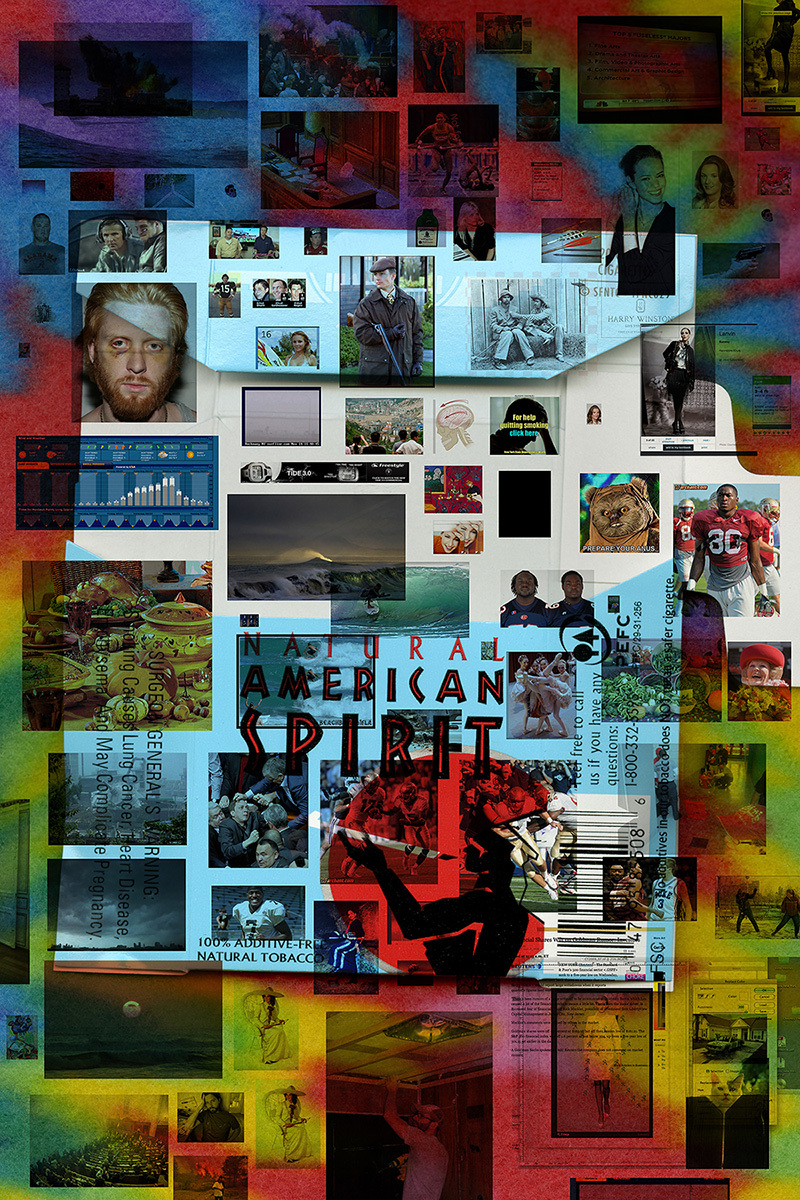

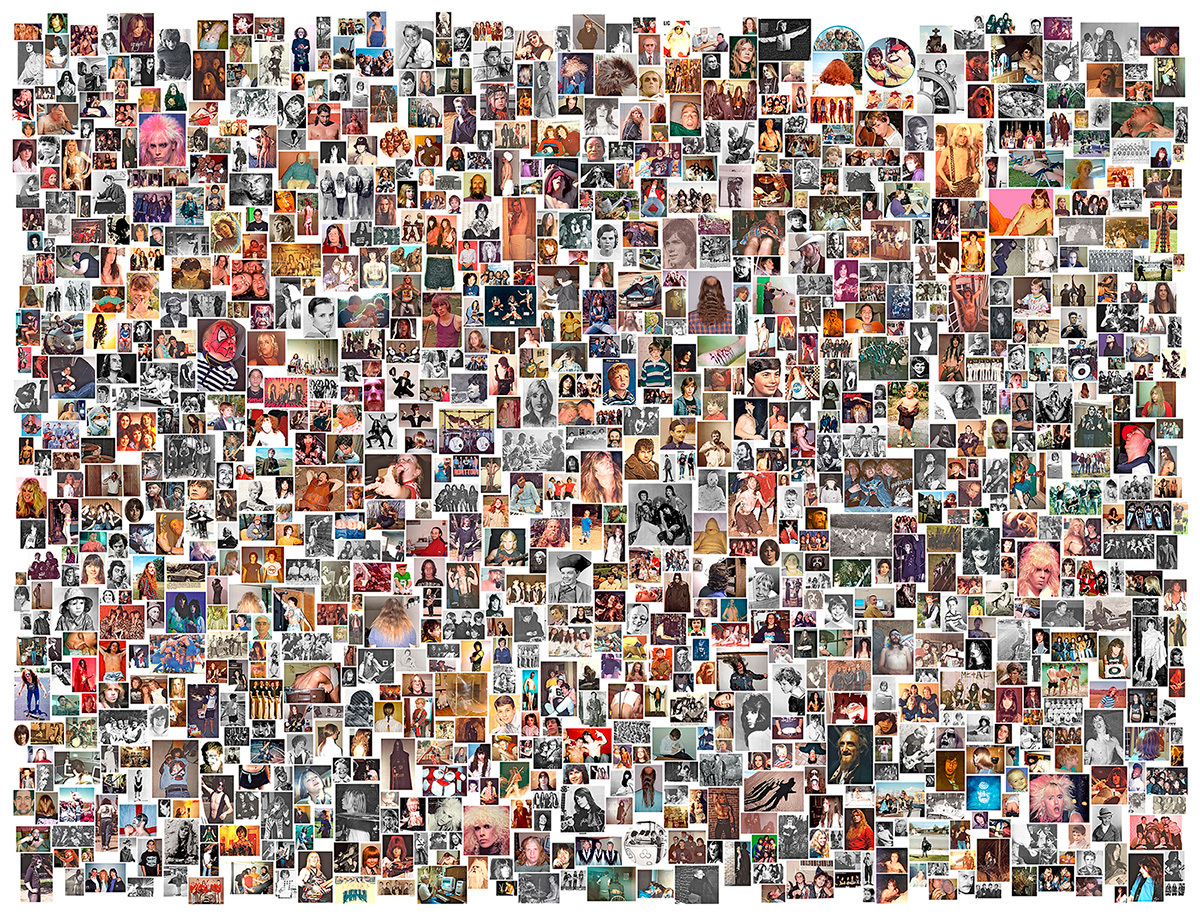

Take for example, the raw power of Barbara Kruger’s politics detournements. Or the subtle refocusing of the art/artist relationship in the work of Louise Lawler, who shoots candid images of famous works in transit, being rehung, or moved. Or Roe Ethridge, who combines his own editorial images with photos culled from popular culture, the web, other magazines, into uneasily over-sensory collages. Or Steven Shearer, whose work Guys, uses thousands upon thousands of found images of guys to present a weird, varied, massive, portrait of contemporary American man. Or, most humanistically, Hank Willis Thomas, who removes the words from adverts, revealing the portraits beneath the hard sell.

Can we sum up as saying, this is a generation who reach towards a vision of America as told through its readymade visual ephemera.

We’re the heirs to the Pictures Generation, still searching for a meaning in the image-wreckage, scrolling through an instant visual archaeology, sifting the massive amount of photographic date bombarded at us 24/7, hunting for some kind of existential sense to be found in the reblogs, likes, uploads, screenshots and slipping away Snapchats.

Credits

Text Felix Petty