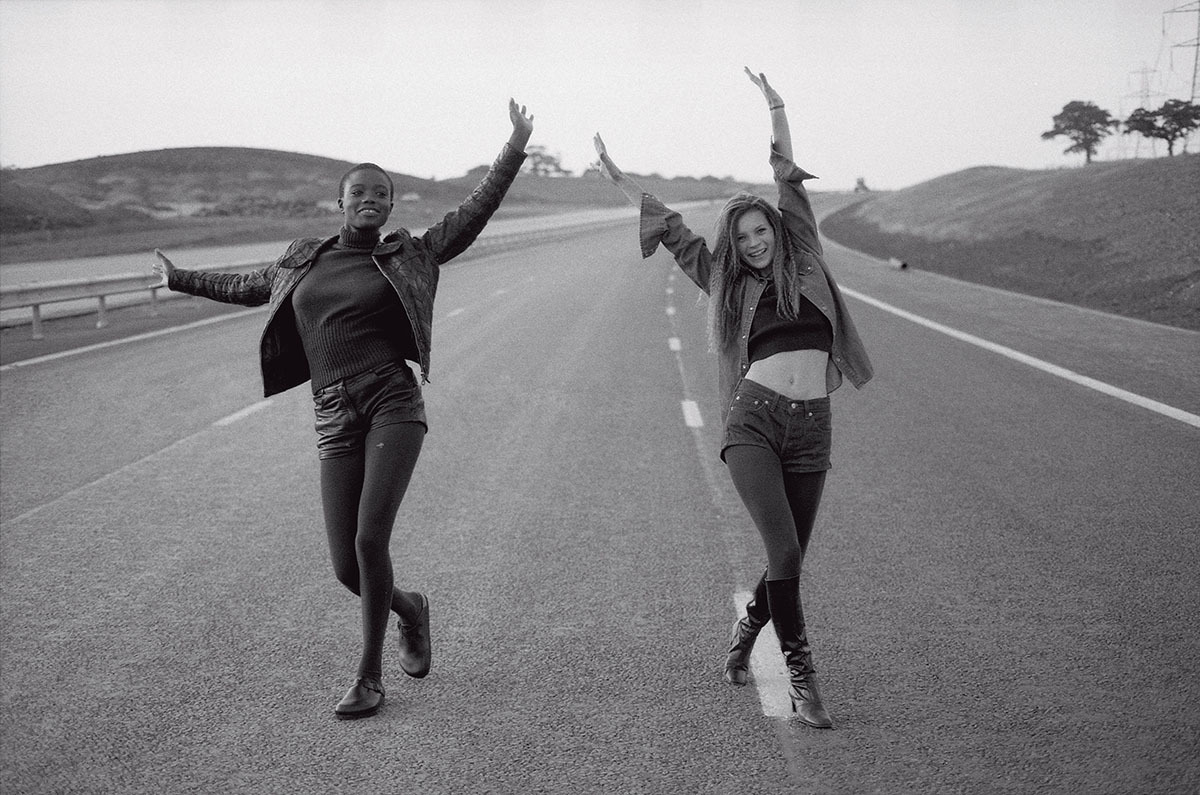

May The Circle Remain Unbroken is an elegiac track from The 13th Floor Elevators’ final LP, Bull of the Woods. It is the sound of shortening-yet-sunny autumn days and reconciliation; this mantra-like recording was also a song beloved by photographer Corinne Day. Her surviving partner, the former model and filmmaker Mark Szaszy, is explaining the importance of the title, which he’s borrowed for a new book and exhibition of Day’s early work. “May the Circle Remain Unbroken started out as a catalogue for 2011’s Heaven Is Real exhibition; it turned into an idea for a book that just went on and on,” Mark explains. With more than 200 images taken from Day’s early portfolios, the work shown runs from 85, when Corinne picked up her camera and met Mark; to 96, when she was diagnosed with the brain tumour that eventually took her life in 2010. Here is the genesis of Corinne Day’s aesthetic and its foundations in the everyday lives of a group of friends feeling their way through the gutters and stars of London – and sometimes, the imperfect but beautiful world outside it. Kate Moss, who Corinne discovered in 90, appears only tangentially. “The title probably comes from somewhere ancient and English, with no copyright,” Mark says. “Because the book started taking its own shape as it focused on people from Corinne’s early era, like Tara St Hill and George Clements, it lent itself to the idea of that unbroken circle of friends. It has a nice ring to it even if some of those friends have fallen by the wayside; may Corinne’s work carry on.”

Corinne liked naturalism; she didn’t like make-up because she knew that any magazine editor worth their salt just wants to see the model’s face. They don’t want to see it covered in gunk. She always wanted to shoot people naturally.

It’s been four years since Corinne’s death and Mark has remained her restless champion. We’re taking stock in deepest south London – I joke that the postcode should be SE2000 – for now, the lodgings he calls home. He’s a long way from the globetrotting life he shared with Corinne. When the door shuts, the suburbs recede; we’re sitting in what appears to be the well-appointed salon of a posh 19th-century spiritualist. A cat, Hare Krishna, slinks by countless stone statues of Bast, the feline goddess of ancient Egypt. The house, a looming grey-brick Victorian Gothic pile, is an anomaly in a street of pebble-dashed terraces with well-tended rose bushes, its dormers capped by those prickly haunted-house spires familiar to all viewers of Scooby-Doo. Mark glances up thoughtfully at the lacy cornicing of the ceiling 20 feet above us, and takes a deep breath.

“This work is from the very beginning,” Mark tells me. “We met in Tokyo in 85, on a train. We were both modelling there, got together and then Corinne had to leave. She got a very big job in America and left for Los Angeles to do the campaign. She stayed there a few years and found a new boyfriend, but for the next two years she kept in touch by postcard. In 87, Corinne showed up in Melbourne, where I was putting together a portfolio to get into the Swinburne film school. She ditched the boyfriend and we fell in love all over again.” Corinne had started experimenting with Mark’s half-frame Yashica, taking pictures around places they visited, and of the people they met on the streets. Mark, who’d established himself as a bald model, posed for pictures with freshly grown hair. When Corinne won a contract for two months’ work back in Tokyo, she invited Mark to join her. “She talked me into taking some pictures and said, ‘Put these in your portfolio, come and see me in Tokyo, and then we’ll travel the world together. It’s up to you.’ And off she went. I had to scratch my head and think, ‘What am I going to do? Am I going to stay here and go to film school, or follow Corinne?’ So I ditched film school and followed Corinne.”

For the best part of a quarter-century, the couple never looked back. Mark eventually became a filmmaker and music video director; Corinne turned to the camera when model fashions changed to favour a more Amazonian look. “Corinne was impressed by the way photographers could gain power in fashion,” Mark remembers. “She started taking photographs of her Milan girlfriends in their cheap pensiones, doing test shots. You can only really get paid to do those in Milan, because models come from hick towns all over the world, without any decent pictures in their books, and can’t get any work. The agencies noticed that the models she shot suddenly started getting work. Corinne was great at taking their clothes and a few second-hand bits and pieces, and turning that into a really nice photograph. Throughout her entire career, she always did that: she took bags of second-hand clothes to Vogue shoots and tried to slip them in if the editor wasn’t looking. The editor was watching, she was aware, but let Corinne get on with it. She added the reality, even back then.”

Today, Mark recognises his late partner’s realness was sometimes too much for an industry that now lionises her. Privately, Corinne worried about being seen as difficult or contrary, and missing out on jobs as a result. Though her parents running off in different directions when she was a toddler blighted her early life, Corinne’s loving grandmother, Mary, raised her in west London’s outer suburbs. “For someone who had all but been abandoned, Corinne never seemed to suffer any crisis of confidence or emotional problems about it,” Mark remembers. “Mary doted on her, and Corinne was fearless. But she kept a lot of her cards close to her chest, especially after she got her diagnosis. Can you imagine having a brain tumour and having to keep it secret, and having it debilitate you to such a degree? We worried the industry wouldn’t have worked with someone who was sick. Corinne felt she could never let on, even to friends, and for years, that’s what she did: kept it quiet. She just wanted to be treated normally.”

Everybody thought Corinne was this super-cool, dark woman, but there was so much more to her. There’s a lot of beauty around us in life. Corinne noticed it, and shot it.

Many in fashion knew she’d had surgery to get rid of a brain tumour, but few realised it was so unsuccessful; Corinne suffered from epileptic seizures for the rest of her life. Soldiering on despite uncertain health, Corinne saved her energy to work and travel while she still could. “We hid out a lot in the last few years of her life,” Mark reveals. “It got hard for her to face people, and nobody was supposed to know she was ill. She had an urgency to earn as much as she could before the end, to buy a house, to get just a little bit of normal security. She was so focussed on doing work because it was the thing she loved most; it kept her going.”

It’s very telling that former models often make great photographers, fashion or otherwise: the hallmark example is Lee Miller, who started as Man Ray’s muse and became one of the eminent photographers of her era. Because she could dress and style the models in a shoot herself, Corinne had advantages over established men who relied on a hierarchy of hairdressers, make-up artists and stylists to do it for them. “Corinne could just churn them out – 14 test shots in one day!” Mark marvels. “She liked naturalism; she didn’t like make-up because she knew that any magazine editor worth their salt just wants to see the model’s face. They don’t want to see it covered in gunk. They want to see the natural hair, how it is, so they can see what they’ve got to work with. Corinne understood that. It also served her purposes too, because she liked natural photographs. She wanted to shoot people naturally.”

The naturalism of Corinne’s work, a thread that runs through her pictures regardless of the setting or subject, is especially evident in the early personal work seen in the new book. As we scroll down the proofs on the screen of Corinne’s old PowerBook, there are constant flashes of beauty: George Clements, draped over a train seat like a latter-day Thomas Chatterton; a ‘pigeon tomb’ in the loft space of a squat in North London; Tara St Hill laughing uproariously in a sparse, almost-empty lounge; pastoral landscapes in rural Britain or the Australian scrub; a solitary little girl playing by herself on the pavement in Milan. Mark thinks the juxtaposition in her work is important – and telling. “It wasn’t right, how people came to see her work – as cool, druggy and from the dark side,” he says. “Everybody thought she was this super-cool, dark woman, but there was more to Corinne, and it’s one of the things I became interested in showing before in Heaven Is Real and again today, saying our life here can be heaven, there’s a lot of beauty around us in this life. Corinne noticed, and shot it.”

Credits

Text Susan Corrigan

Photography Corinne Day

Originally published in The Creative Collaborators Issue, i-D No. 327, Fall 13