Shane Gabier and Chris Peters have an obsession with the obscure. As Creatures of the Wind, the New York-based duo has gleaned inspiration from figures as diverse as Japanese graphic designer Ikko Tanaka, Twin Peaks siren Julee Cruise, and Biollante (Godzilla’s only female enemy, a giant flower monster). Yet this individualism is never alienating. You don’t need to be fluent in the principles of 1930s industrial design to want to wrap yourself in one of Creatures’s rich coats, or to find the joy in its flowing lamé dresses. Ask Britney Spears.

Much is the same for Valerie and Her Week of Wonders, the movie Gabier and Peters have selected for i-D’s “Fashion and Film” series. The semi-obscure piece of Czech cinema blends elements of fantasy, gothic horror, coming-of-age, soft-core erotica, and religious folklore. It’s inspired by fairy tales like Alice in Wonderland and Little Red Riding Hood, but out-weirds them by a mile with heavy helpings of 60s phantasmagoria, fluid sexual desire, and a bewitching choral score. “The way that we design is often very narrative-driven and very atmosphere-driven,” Gabier explains. “I think the films that we’re often attracted to work the same way.”

Valerie is considered a cornerstone of the country’s New Wave movement. Released in 1970, it was made “just as Czechoslovakia succumbed to the gray strictures of ‘normalization’ following the Soviet invasion in 1968,” explains Jana Prikryl in her Criterion edition accompanying essay. This context is helpful in understanding the film as a work of creative dissent, but not essential to its enjoyment. In fact, critics have generally found the opposite to be true. “Viewers willing to just accept Valerie’s beautiful surrealism will probably feel their time was better rewarded than those who will need to have it all figured out,” says Under the Radar.

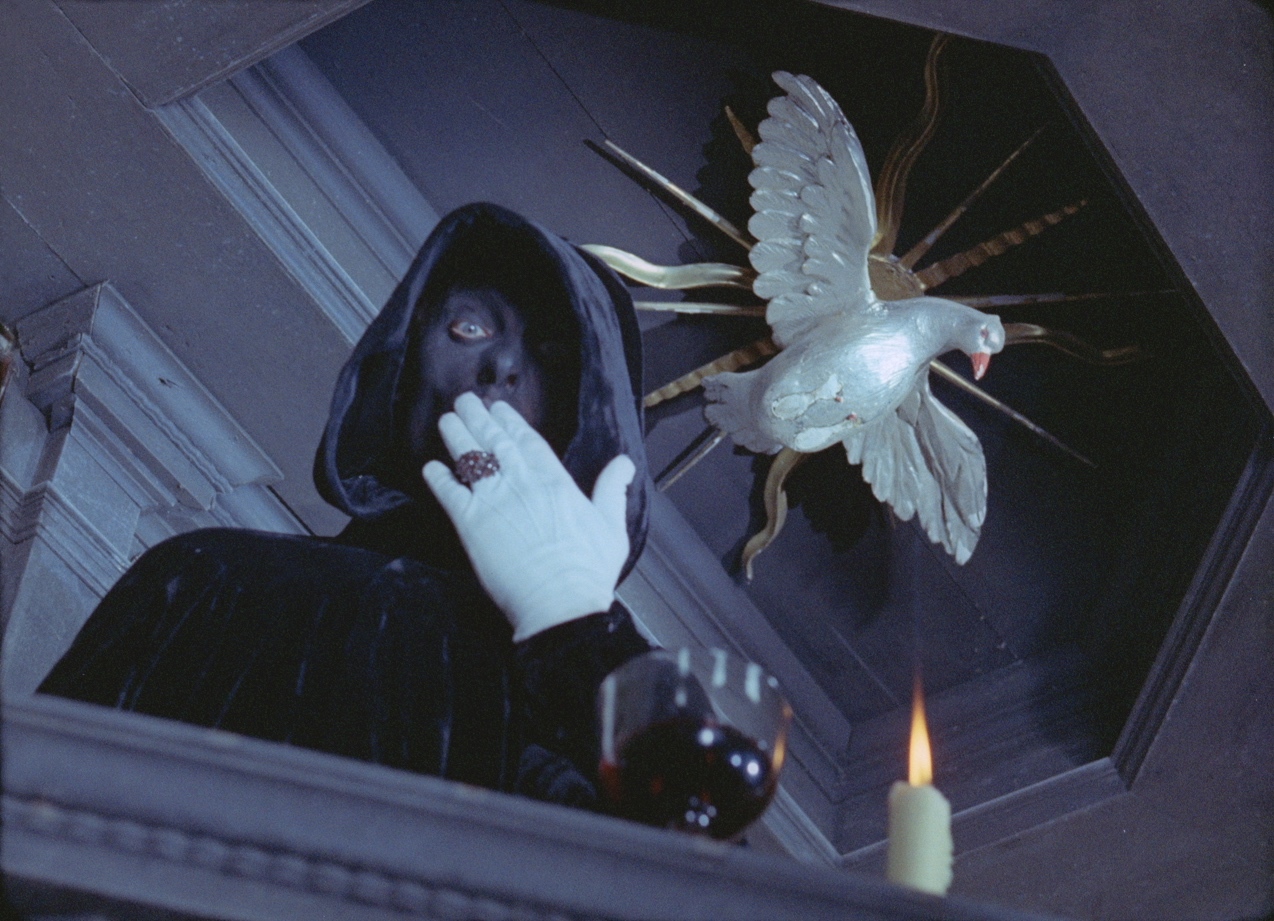

Based on a 1945 novel by Vítezslav Nezval and directed by Jaromil Jireš, Valerie follows its 13-year-old title protagonist’s sexual awakening. The A.V. Club describes it best as “a hallucinatory portrait of pubescence” in which the line between dreams and reality, danger and safety, nature and artifice, agency and exploitation, religion and sex are not just blissfully blurred, they’re outright transgressed. But (much like how we discover our desires off-screen) these slippages can be playful, sometimes pleasurable.

“I think there’s a kind of nebulous morality to the whole movie,” Peters explains. “You don’t know what anyone’s intentions are. Everyone is kind of everything all at once. Grandma isn’t just loving, super-Christian grandma. She’s also, like, a sex vampire.”

This constant shape-shifting isn’t solely grandma’s domain. The film’s main sex vampire sometimes appears as a hunky redhead; at other moments, he’s a campy cross between Nosferatu’s Count Orlok and Aphex Twin’s “Windowlicker” visage. (This man is meant to be the film’s scariest character, but it’s a hard sell when he carries an adorable puppy everywhere). Valerie’s primary love interest is, possibly, also her brother. People die, then simply open their eyes and keep things moving. It’s unclear where exactly each scene takes place — or even how the rooms in grandma’s house are connected to one another.

“I think it treats the characters the way you often see characters in dreams,” says Gabier. “The faces are familiar, but you can’t really pinpoint who anybody is or what they represent exactly.” Such an untethered reality can be maddening, but it’s also rather liberating. “There’s so much symbology in the movie, but none of it actually relates to anything,” Peters adds. Surrendering to Valerie’s surreality enables a greater appreciation of its biggest strength: its visual splendor.

Shot during the summer in Slavonice (a picturesque Czech town dating back to the 12th century) and its surrounding forest areas, Valerie playfully reminds us of the divisions between natural, religious, public, and private spaces as it undoes them. We almost never observe its action in a straightforward sense. Most scenes are shot from extreme angles above or below the players; some are filmed through bunches of flowers, or flames. From a costume perspective, Valerie is a knockout. Find me a sex vampire grandma who can accessorize better than this one.

“I think it’s one of the most visually arresting films I’ve ever seen,” says Peters. “And it’s definitely something that stays with you. Nobody forgets that they watched this movie!”

i-D’s “Fashion and Film” series begins August 3 with Valerie and Her Week of Wonders. Learn more and buy tickets here.

Credits

Text Emily Manning

Stills from Valerie and Her Week of Wonders courtesy Nitehawk Cinema