At this point in the year, we’ve seen an entire micro-generation of bright young creatives overcome the unforeseen circumstances brought about by the pandemic and graduate. Doing right at the end of 2020 are the five members of Central Saint Martins’ MA Fashion Communication: Fashion Image Class of 2020. Across disciplines of photography, styling, film and even web development, they have, between them, tested and stretched fashion’s expressive capacities, creating within constraints that none of their predecessors faced.

Each of their projects — which explore topics as far-ranging as radical joy, personal myth as a conduit for decolonisation, and the hybridity of Catholic visual culture and everyday life — is a testament to the times in which they were produced; each a considered social commentary filtered through fashion’s lens. Here, the five graduates share the inspirations behind their projects, how they overcame isolation, and the messages they hope their work conveys.

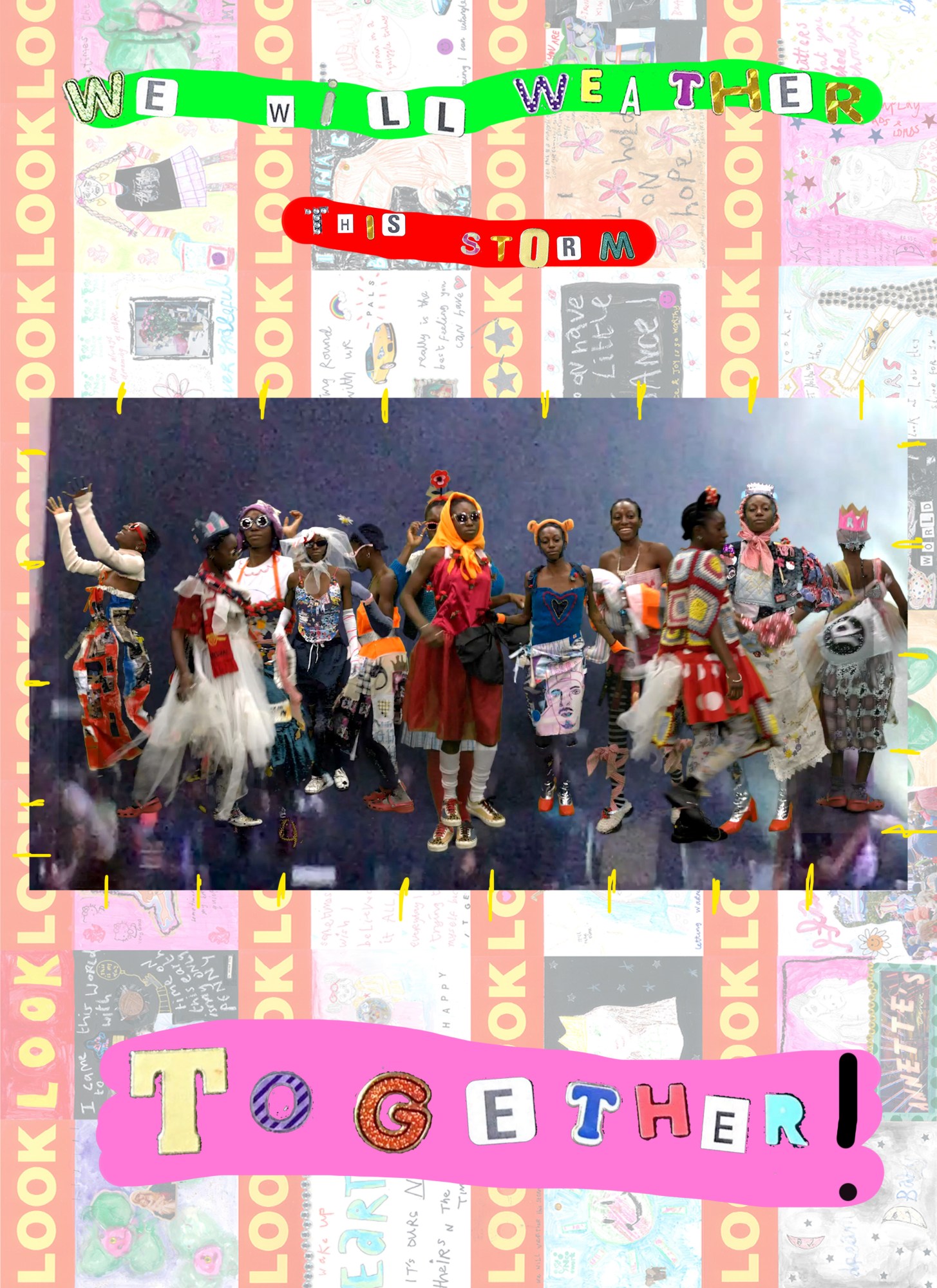

“My final project consists of two parts: a book/party bag called ‘Dream Baby: I am my own sunshine (1995-2002)’ and a film called ‘we will weather this storm together!’ and I hope they make people smile a lot! I looked at the ideas of collective joy and radical happiness and how they could be translated via image-making to enable myself and those who see the work to feel stronger in our capacity to deal with the time when the skies might be grey. The ‘1995-2002’ part of the work comes from a realisation, due to family difficulties and tough times, I didn’t have many memories from the first 7 years of my life. It felt like my brain was blocking it out and I wanted this project to be a chance to create joyful moments with the people I love which could fill the gap.

“When lockdown struck I felt quite worried and sad that I had lost the physical space and community that I gained by going back into education. However, I realised that the only way to get through it would be to realise how lucky I was to have so many wonderful people in my life and to connect how I could. This pushed me to work more collaboratively and to investigate how collective joy could exist in this time. This is also present in my book as Geri and Jess (also from the MA) designed it. It also led me to think about the issues within group experiences for those with access needs; my mother is disabled and so it is always present in my life, and the sensory issues for those who may be neurodiverse. Class will also always play a role in my work as I credit everything I make to being raised around working-class superstars on council estates who are endlessly strong and find joy in each other when there isn’t much around.

“I think anyone in any career should use their spaces to challenge and advocate for equal representation and this is definitely needed within the arts. In general, I try to live my life like this; I don’t separate it from my work, and I always want anyone who is working with me to feel comfortable and represented. Collective joy is about using these emotions to enable us to sustain our resistance to power structures and oppressive forces, so I hope my work can add into the discussion of this and to show how much we need and deserve to feel good. I also try to integrate giving back in ways I can; for example, the profits of the book will be going to four charities-Solidarity Sports, Key4Life, Dad’s House and The Gate. I think we have responsibilities to our world as humans to be actively anti-racist, share our platforms and aim for our voices to be a positive not a negative addition to spaces.”

“My final project — a series of portraits and a short film — introduces an amalgam of narratives. Utilising both traditional and more experimental avenues of portraiture, I and various women explore personal myths as tools for decolonisation, dissecting and recontextualising African, Caribbean and Indigenous depictions through an anecdotal lens.

“Looking at the subject of decolonisation, I was intrigued by the idea of creating a new world, even if just through imagination. Having digested imagery from artists like Paul Gauguin, and photographers like Peter Beard and Carl Van Vechten, I wanted to see how the decolonisation of imagery could be possible through re-authorship, and the changed gaze of the image-maker. I really wanted to encompass the idea of the personal myth as a tool for liberation: creating contexts for intimate, and often self-guided, narratives.

“Identity politics have kind of always been inextricably woven into culture and fashion. And as a Black woman, rather than responding to the hot topic of the moment, race and gender have inherently come to inform how I see things, and what I think we need to see more of. I like for my imagery to act as a catalyst where me, the subject, and the viewer can all engage in this sharing of emotional information, hopefully leading to a greater degree of connection and understanding with one another. I’m really interested in the capacity for images to act as a tool for liberation — be it due to race, gender, sexuality, disability, or the basic human condition, I’d like my work to be a sort of platform for us all to find release through presenting and connecting with the truth of ourselves, refuting the perpetuation of the trite white supremacist, capitalist, patriarchal gaze.

“Creating in isolation was difficult due to the lack of engagement with other people mostly, but also the lack of access to equipment and materials. In a lot of ways, though, restrictions allowed me to reconsider my practice. My bathroom became a darkroom and I found myself breaking down other barriers by sheer force of having to readjust to things. I took self-portraits, and started having conversations with a lot of different people around me and it just allowed this bridge to form, bringing forth so much beauty from new friendships, collaborations, and just the pace of making work and engaging with it in a more considered sort of way.

“My grandmother Rosa was my first connection to clothes. Since I was born, she has shared her love by making beautiful dresses for me. I often encounter myself lost in blurred memories of her in my home country of Venezuela, of the days when she used to bathe and dress me. Rosa’s mother, Cayetana, was an indigenous Black woman who was taken from a young age to serve her own father’s family, relatives who mistreated her for her skin colour and bastard origins. I chose Cayetana as the title of this project because I see her as the beginning of our lineage. Analphabetic and alone with three kids, she took the brave decision to leave her rural home in Altagracia de Orituco and start a new chapter in the capital Caracas, searching for better opportunities. This project is a love letter to the women of my maternal family tree. With my photographs, I take pride in honouring the women who have shaped me but are not physically with me.

“Motherhood and the role of women are the main themes. I am interested in celebrating the lives of Latin American matriarchs: powerful, beautiful, and hard-working women like my ancestors, who are my personal heroines. Additionally, domestic crafts were also part of the process. I initiated this piece due to my desire to weave my grandmother’s delicate, fragile, and beautiful story to persevere against the passage of time, reliving memories saved in the corners of her mind. Inspired by the way she used her craft to give birth to dresses, I use the medium of photography and handmade objects to create tangible images.

“Since my intentions to visit Venezuela to produce the project were not possible, I had to adapt and reinvent my original plan. It was a challenge to explore my roots while being away from home. In order to portray a sense of location, I turned my attention to the process of making handmade items and props to evoke elements from my childhood and my country. Some creative ideas were born out of the necessity to fill the physical distance. The work of Marisol Escobar, an artist of Venezuelan heritage, inspired the last photograph of the book, a family sculptural portrait made with old photos, secondhand clothes and cardboard, in which I included myself.

My work has always been an outlet for me to celebrate the lives of women, teenagers and children in a time of economic, social and political unrest. As I was ending this project, I found myself staring at my photographic series Nosotras, my first real connection with the medium of photography. Struck by the unrecognised role women play in Venezuelan society, I sought to celebrate the collective real-life heroes of my homeland, beginning with women who aren’t related to me. But after I found myself strained and prohibited from holding the women I love most, I created this photographic melody to celebrate the fertile mestiza women we are. Since I emigrated, I have felt the necessity to return home and document the lives of my people while they are immersed in crisis. In my project Venezuelan Youth, I document the lives of the kids and teenagers with a hopeful approach. I search to portray a break from their struggles, wishing a happier and better reality for them. I believe I have a responsibility to my country to make use of the privilege I was born with.

“My final project reflects my personal relationship with my mother tongue. Having migrated to the UK at an early age and not really fitting in with either cultures, I wanted to make a body of work that explored the process of trying to solidify a Lithuanian identity. While at my family home during lockdown, I started to have conversations with my sister and mum about what it means to have lost touch with a mother language and this continued whilst at CSM through interviews with girls who have experienced a language shift at home too. By exploring family archive imagery and referencing this in my own work, I created my own visual language in the attempt to replace the language that was lost, my own version of ‘Lithuanian-ness'.

“I think being in isolation has caused everyone to be a bit more reflective over their sense of self and this is what this project was born out of. Being around my mum and sister on a more constant basis helped us to explore the idea of language together and bring forward conversations that we wouldn’t normally have.

“The idea of sharing ideas and recipes in a space that is friendly and welcoming mirrors my experience of speaking Lithuanian at home with my sister during lockdown. It is an inviting space free of judgement; something that we also created during the group crits while at CSM with the other girls on Fashion Image. These ideas should be more present in all aspects of society and I believe a kinder approach should be taken when considering politics of all nature.

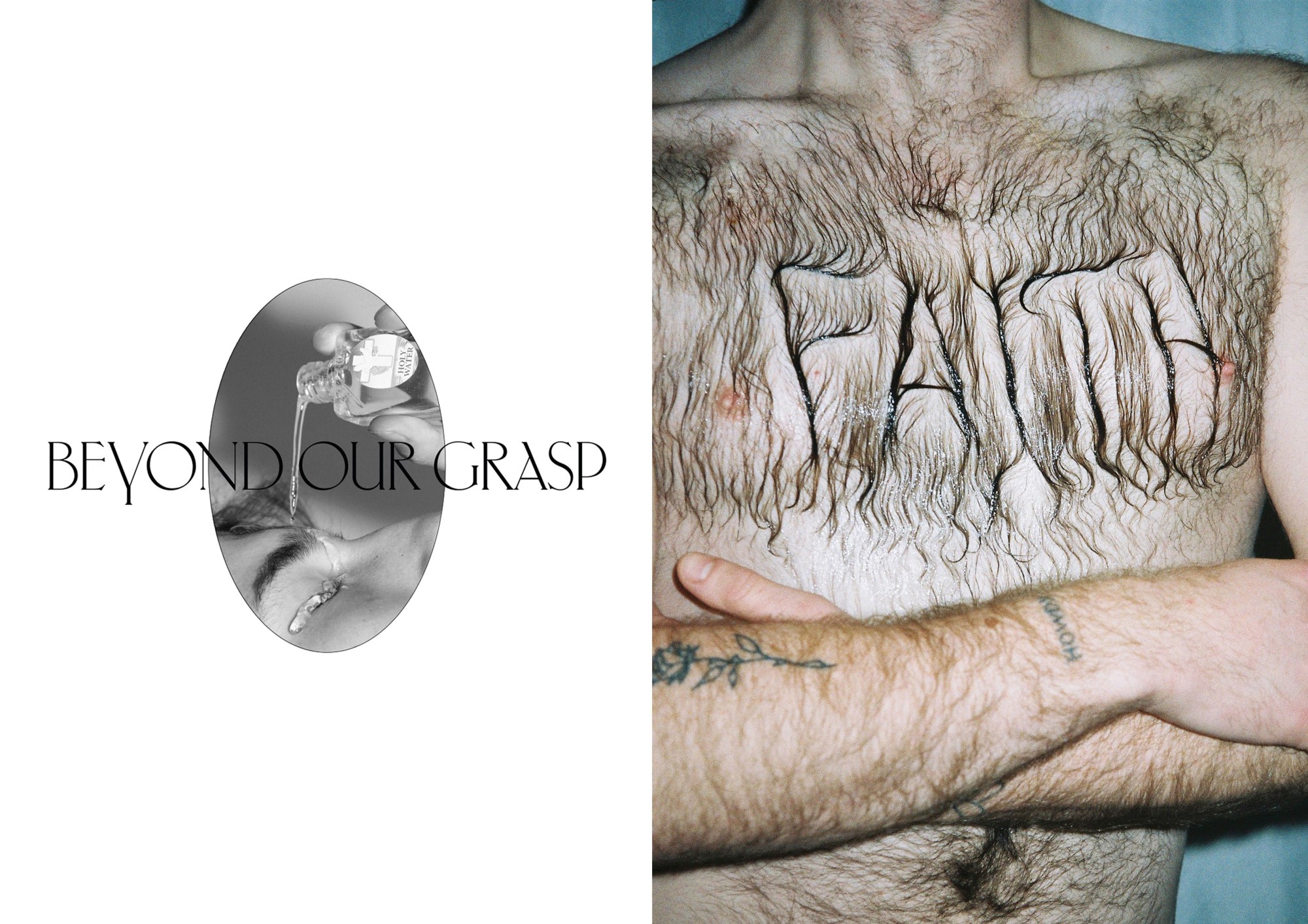

Beyond our Grasp is a digital exhibition exploring the hybrid nature of modern religion, performativity and our relationships with objects. As generations adapt to a world with less faith, I have created an audiovisual experience tackling the physical symbols and touchpoints of faith and the idea of fashion as embellishment to our daily performance.

“Essentially, the project is rooted in faith. However, it has very much become an examination of the quaint idiosyncrasies of belief that feel intrinsic to a Catholic upbringing. Initially, I wanted to cover faith as a broader spectrum but working through the project, I had realised this indoctrination of the rituality being raised as Irish meant the project could only go one way. The blending of culture and religion is ever-present, whether you are raised Catholic or not. Often, most of the historical roots of Irish tradition steps further back than religion and are rooted in pagan folklore. Language is also highly resonant in the project. A great example of this being “Dia Dhuit” meaning Hello but is a direct translation of ‘God be with you’ and this only serves to echo just how omnipotent it is. The hybridity of belief with daily lifestyle, from colours and clothes to symbols, is what has become the backbone of Beyond our Grasp.

“Exploring something as large and monumental as religion and faith, one can’t consider it without thinking about how identity comes into it. In modern-day Ireland, the church is completely linked to health care, education and political structures. An interview I had with a Catholic priest echoed my thoughts, when he conceded that being a young person with faith is essentially a subculture in 2020. As a country which sits in a limbo state of belief and referendums to undo the Church’s damage, it felt important to me to understand these unspoken codes which particularly affect the experience of marginalised groups in Ireland.

“The restrictions of lockdown led me to focus more on the digital work. I spent most of lockdown coding and was able to use this to inform how my work is displayed. As our daily routines were disrupted and our plans led awry, a lot of us were forced to examine the lives we had led on autopilot. I went back to Ireland for the lockdown and was reminded of what had raised me as I had spent so much time away from there. This definitely shaped the project thematically but the time also allowed me to develop my skills in a practical sense. In a time when touch and material existence was disrupted, I felt myself naturally led to adapting what I did to the digital realm.