This story originally appeared in i-D’s The Ultra! Issue, no. 369, Fall 2022. Order your copy here.

Is this the look of the apocalypse, as everyone from Nostradamus to televangelists have prophesied? Or is it just the outfit for an everyday excursion in downtown Shanghai? It was certainly the look at the Rick Owens menswear show in June in Paris, staged in the brutally scorching courtyard of the Palais de Tokyo, where three giant globes were elevated to the heavens by machine-operated cranes, set alight, and then dropped in all their flaming glory into the vast courtyard fountain.

It conjured scenes of Armageddon, flaming suns crashing down to earth. “The cycles of evil and useless destruction just repeating over and over since the beginning of time,” was Rick’s simple explanation. His show, by coincidence, took place on the same day that the US Supreme Court overturned its 50-year-old decision on Roe v. Wade.

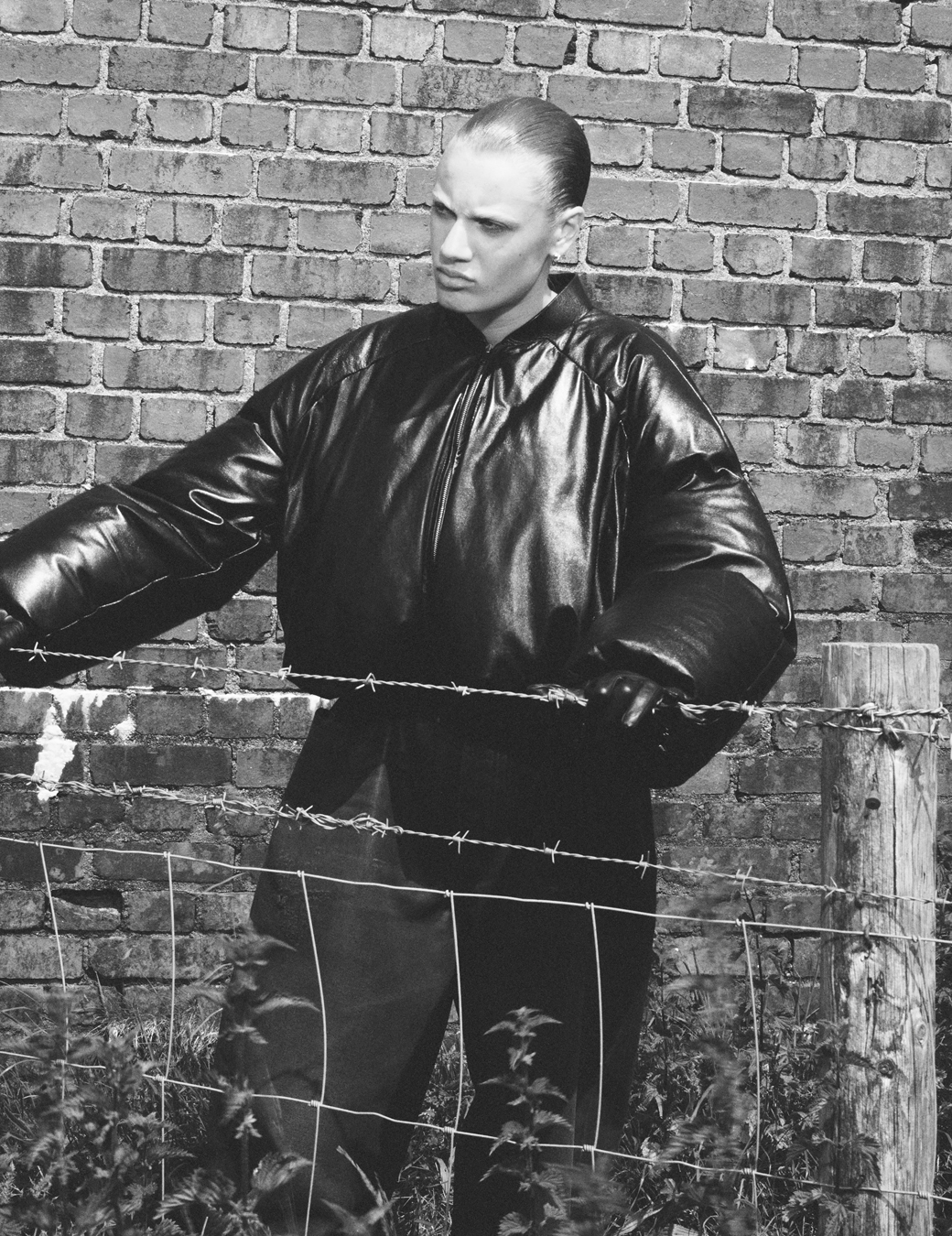

Fashion, often accused of being the greatest cause of the end of the world, is currently reflecting on that sentiment, and what may have once seemed like a faraway sci-fi fantasy, has become the prevailing mood of shows from New York to Paris. Sure, there are bursts of ebullient light designed to lift our spirits and distract us from our breakneck journey toward global disaster – with sequins and frou-frou to sweeten the bitter taste of bad news – but for many designers, fashion has become a space to reflect on our broader anxieties and fears; on the darkness and isolation of contemporary urban life. Theirs are clothes which echo the many placards held outside subway stations around the world that proclaim ‘The End Is Nigh’.

These days, most news is bad news: estimations that the climate crisis will tip over into irrevocable catastrophe, landmark human rights laws being overturned overnight, or the horrors of war that the world swore to never let happen again happening all over again. The latter of these unfolded during the womenswear shows in Paris in March, with editors and buyers on the fashion circuit constantly scrolling through fresh horrors in between shows and appointments. Designers spent months working on their collections, only for the context in which their work was presented to shift from post-pandemic joy to post-apocalyptic violence in just a few days.

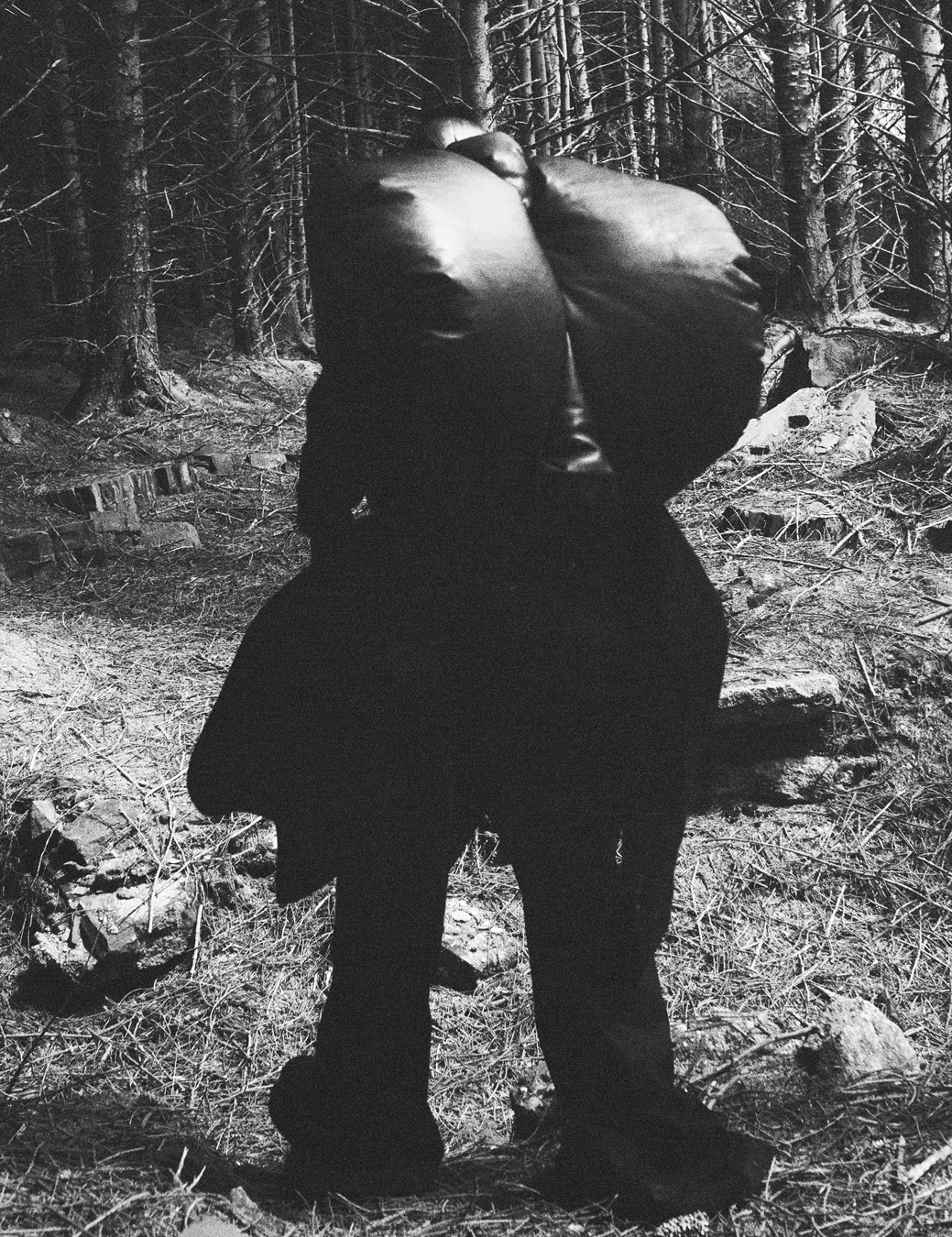

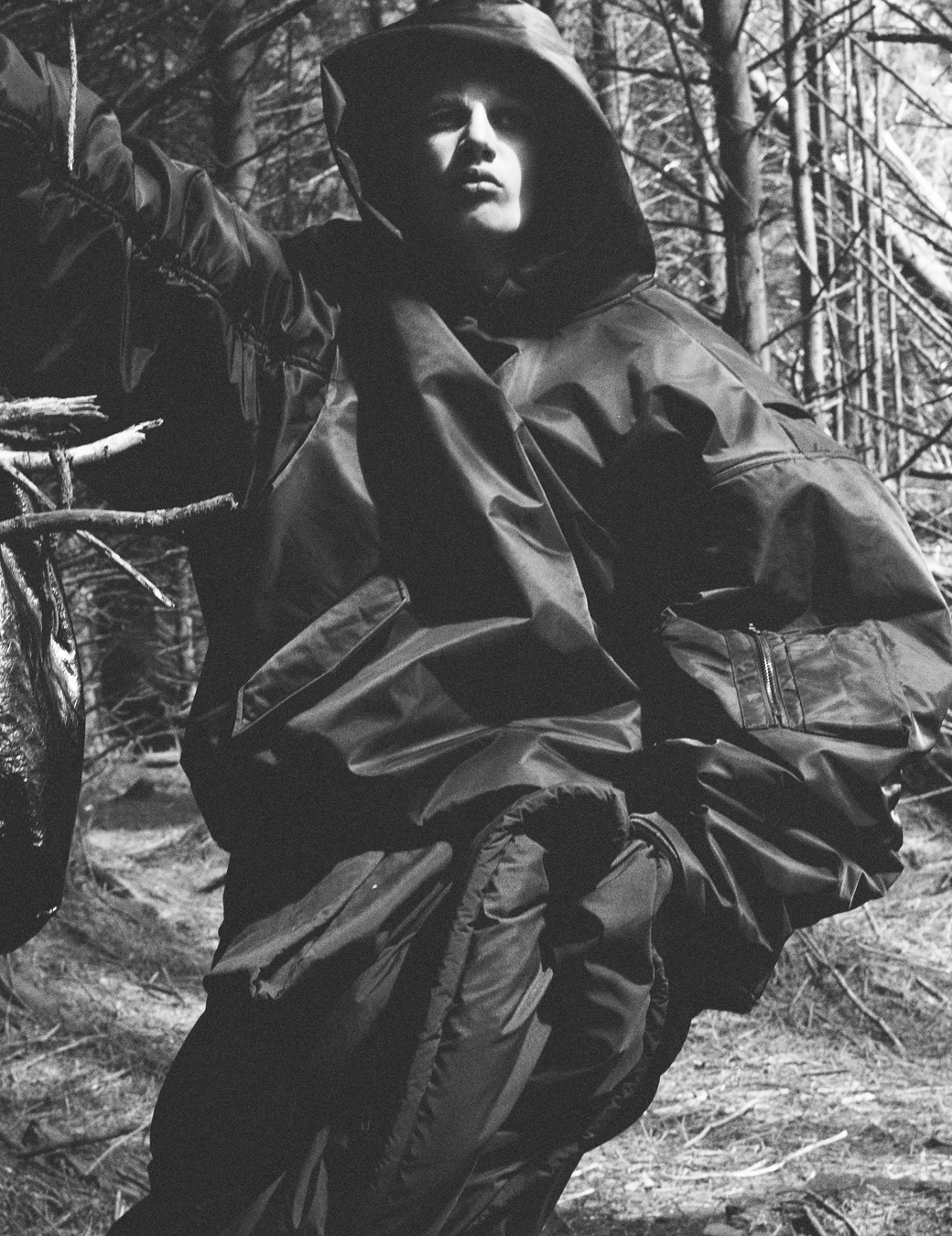

The show that made the most lasting impression as a mirror to the moment was Demna’s for Balenciaga. Held in a giant purpose-built snow globe and originally conceived as a commentary on the climate crisis, models trekked through gale-force winds in a dramatic snowstorm. Shivering in skimpy layers taped together by gaffer tape, they carried their belongings in luxe pauvre leather bin bags, hiking through the fake snow with visible difficulty in their pointed stilettos. Some were in giant puffers and hoodies, others dressed in little more than underwear and a Balenciaga-branded towel, almost as if they had been forced to flee mid-shower.

What could have so easily been interpreted as an outrageously distasteful let-them-eat-cake moment was immediately understood as a creative vindication of Demna’s childhood trauma: trekking across the Caucasus mountains as one of the 250,000 Georgians forced from their homes by Abkhazian separatists during the country’s civil war. Knowing first-hand the terror and brutality currently being inflicted upon Ukraine by Vladimir Putin, his show reflected a moment in which 1.5 million people were fleeing Ukraine in the fastest-growing refugee crisis in Europe since World War II: a community of people moving through the wilderness with only the clothes on their backs. For them, the world as they knew it was over.

“In a time like this, fashion loses its relevance and its actual right to exist,” read the note placed on every seat atop a T-shirt in the colours of the Ukrainian flag. “Fashion week feels like some kind of absurdity. I thought for a moment about cancelling the show that I and my team had worked so hard on and which we were all looking forward to. But then I realised that cancelling this show would mean giving in, surrendering to the evil that has already hurt me so much for almost 30 years.”

Fashion may not have the answer to every issue, geopolitical or environmental, but it can certainly capture the zeitgeist. Was Balenciaga’s show uncomfortable to watch? Absolutely. Yet Demna provoked what no other show had achieved – a rousing empathy for the people who had lost everything, including their homeland. Though the concept was symbolic, there was an underlying dare to desire the clothes, and this paradox was so tense that it served as a reminder of fashion’s power to titillate, to challenge the parameters of conventional good taste, of desire and damnation.

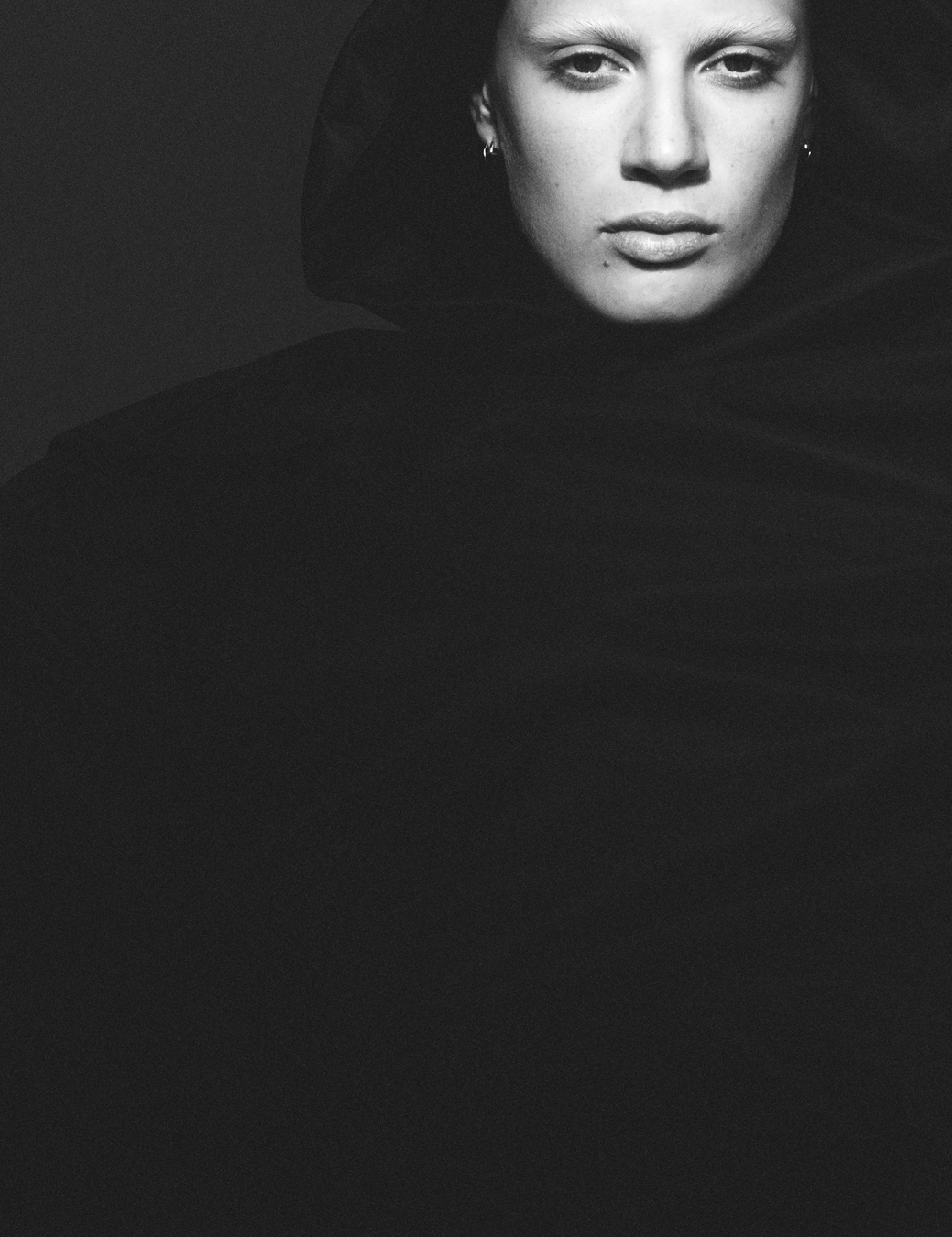

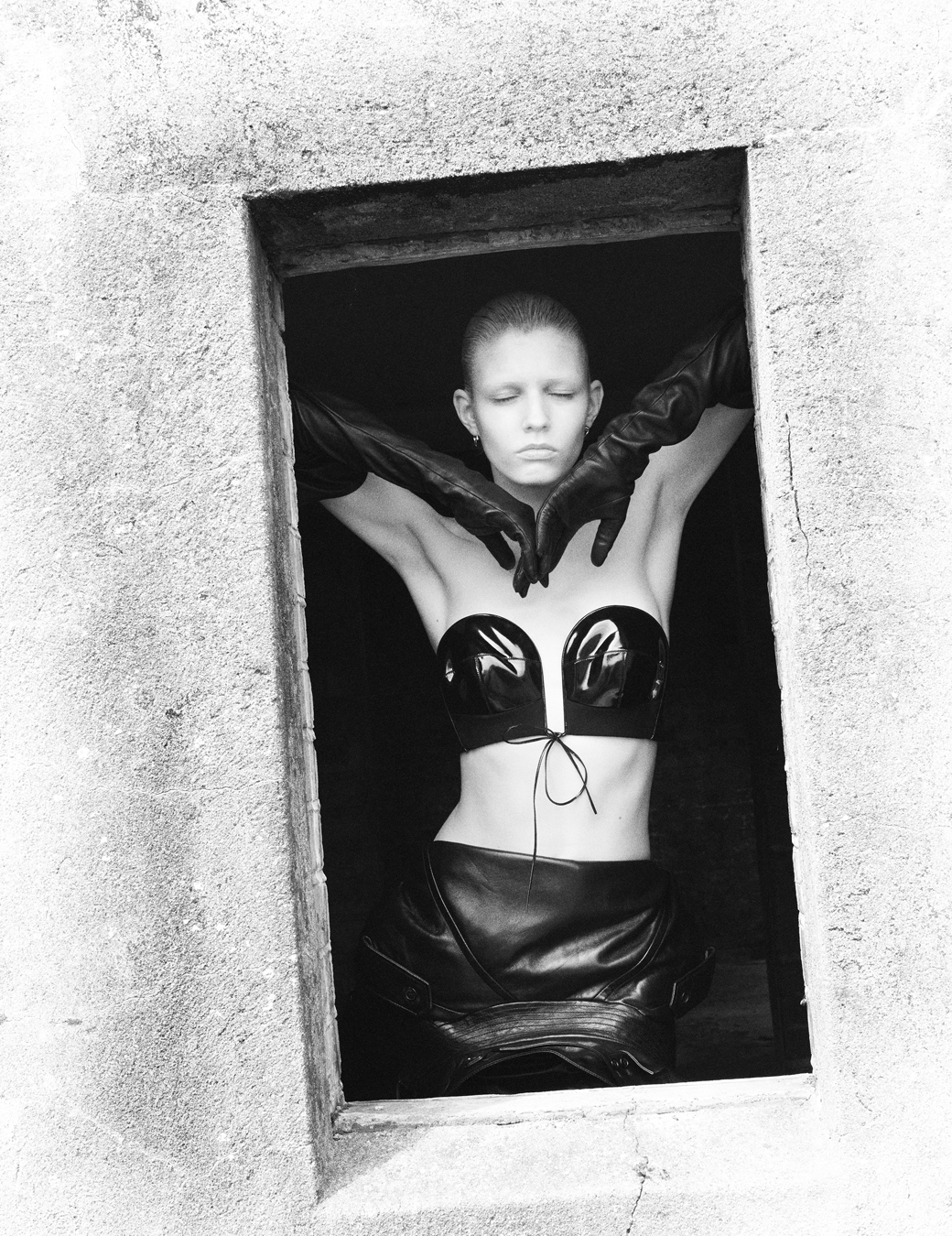

Of course, this is nothing new. Visions of post-apocalypse have been circulating for a while – the uniforms of sanitation workers hinting at rising sea levels; buckled-up, strapped-in hazmat suits suggesting toxic fumes rising from inadequately ventilated landfill sites. There have been Blade Runner-esque algae greens, flashlight neons and asphalt blacks all over department stores; shaved heads and blackened eyes in beauty campaigns, just like Rachael’s in that same, seminal movie (which was first released in 1982, but was presciently set in 2019).

And just as Blade Runner influenced a generation of designers such as Vivienne Westwood and Jean Paul Gaultier at the time, the release of a new Dune film last year apparated a mirage of medieval sci-fi and desertscape looks from Kim Jones at Fendi and Nicolas Ghesquière at Louis Vuitton. Saint Laurent cemented it with a show in the Moroccan desert that culminated in a towering Stargate-like light display emerging from the bottom of a specially-made body of water — it was a totally surreal symbiosis of branding, technology and the wild beauty of Mother Nature. And clothes. Of course.

Elsewhere, designers have experimented with frayed edges, raw materials and discombobulated silhouettes, not dissimilar to the way that Comme des Garçons’ radically punctured knitwear challenged the meaning of luxury in the early 80s, or Elsa Schiaparelli’s 1937 ‘Tear Dress’ that featured purplish pink bruises and strips of trompe l’oeil torn flesh. Scroll through the rails of Dover Street Market and you’d be forgiven for thinking the shredded, cobweb-like knitwear and balaclavas of LA-based label Airei have already decayed –and indeed, the label’s designer Drew Curry intends the pieces to fall apart with wear – a reminder of the temporality of our prized possessions. Nothing lasts forever. An installation Drew created at the retailer’s Paris showroom, 3537, earlier this year was aptly titled: The Case for Tragic Optimism.

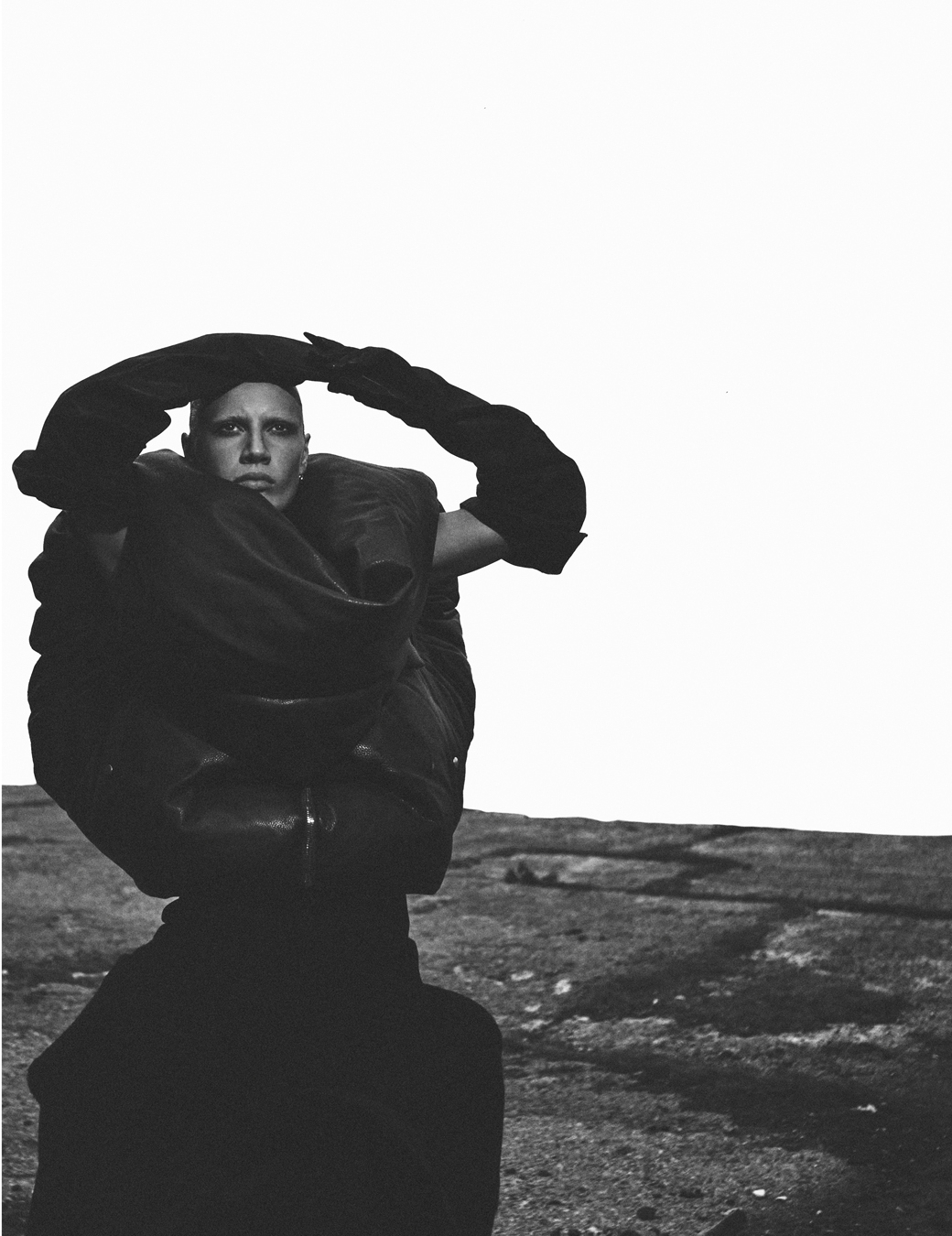

For Marc Jacobs, a return to ready-to-wear after a pandemic-induced hiatus offered the opportunity to reflect on the weirdness of a new hybrid reality for SS22; somewhere between before and after, where we’re all trying to find personal equilibrium within a new world order. Dramatically sweeping silhouettes came with a kind of dishevelled, faded grandeur. Disco paillettes slashed and wrapped into hungover cocoons; multiple pairs of cargo pants sewn together and transformed into long skirts; jersey sweats deconstructed into sarcophagus ribbons that mummify bare skin, paired with opera gloves and denim stoles – these are dresses for an end-of-world party, because what is there to do when all hope is lost but to desperately try to have a good time?

For the most part however, fury has given way to despair and designers have been swimming upstream to find some kind of optimism. “We have art in order to not to die of the truth,” as Marc Jacobs quoted Nietzsche in the show notes for his following AW22 collection, which appeared equally dystopian with DIY materials that included foil, glass, paper, plaster, plastic, rubber and vinyl.

Echoing that notion, Rick Owens explained that although his aforementioned show was ostensibly about flaming rage, his message was actually about “the triumph of good over evil”. And it’s true that the geometric white tailoring, jolts of fuchsia chiffon, marigold python trousers and billowing shirts provided a lightness to the pervasive bleak chic look. “I’m always trying to reassure myself that whatever is happening in the world right now – whatever conflict or crisis or discomfort – it’s happened before,” he said. “Somehow, goodness has always triumphed over evil, because otherwise, we wouldn’t be here now.”

Generational angst and panic, heightened by the push-notified news cycle, means that it has never been harder for designers to balance a love for adornment and celebration with the pressing realities of environmentalism and social injustice. Then again, there have always been threats of apocalypse: wars; terrorism; computers malfunctioning upon the millennium; asteroids; alien invasions; market crashes. Ultimately, those who lean into the murky void of the unknown are resonating with a generation who now demand more from fashion than just clothes: brutal, if not poetic, reality.

“You have to acknowledge it, but you can’t succumb to it, and you can’t devote yourself to it and you can’t completely ignore it,” Rick answered when asked about wearing his ideological beliefs quite literally on the sleeves of his designs. “Any kind of fashion is important communication – it’s personal information – but it’s also an awareness of where you are,” he continued. For those of us without a clue where we’re going, there’s something reassuring in the creative articulations of where we are right now. However dark, however angry, however hopelessly apathetic that may be – it’s something to echo our moods and protectively adorn our bodies, perhaps even prepare us for our darkest fears and anxieties as they unfold before our eyes. Too real? This is fashion for a very bleak reality.

Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more from the new issue.

Credits

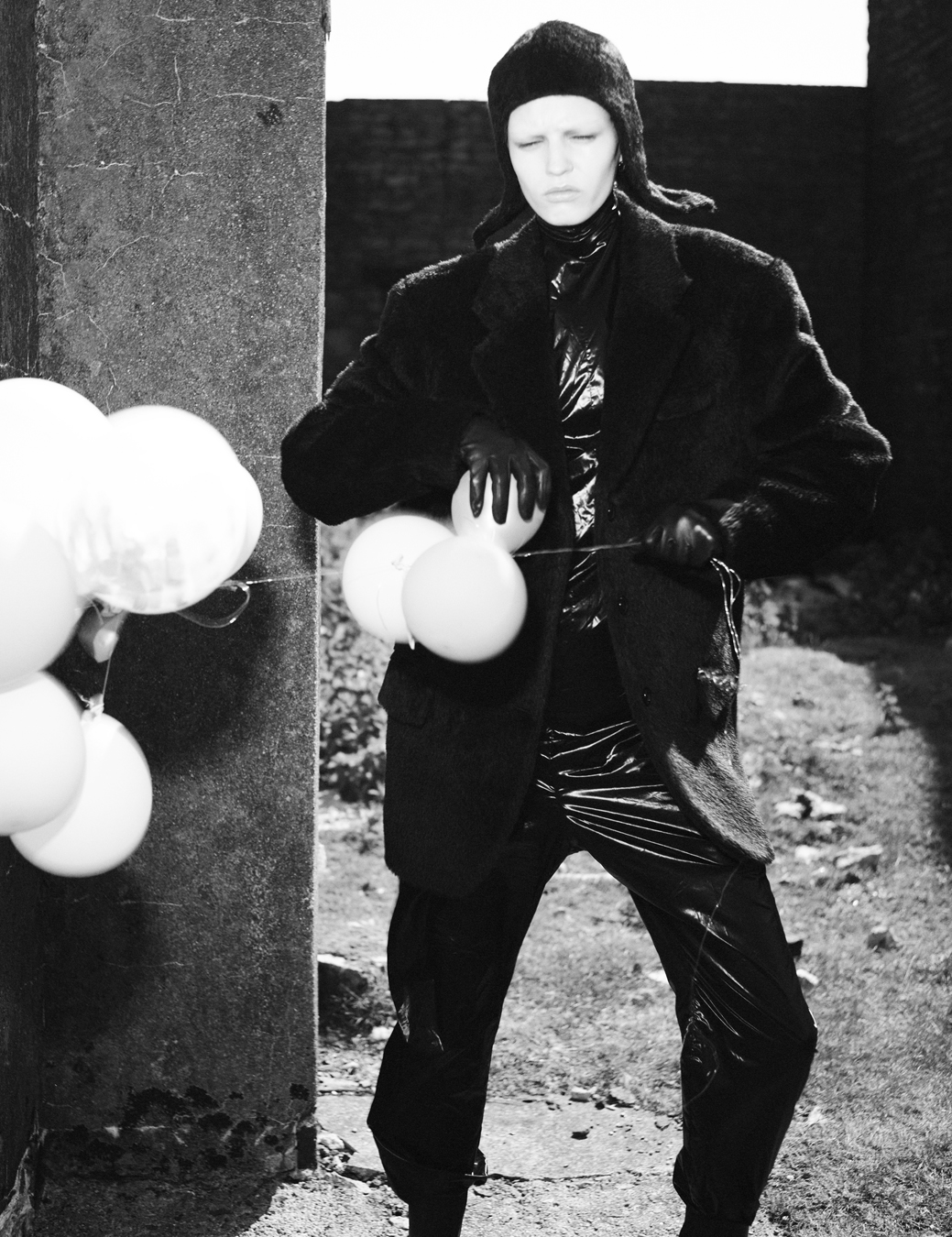

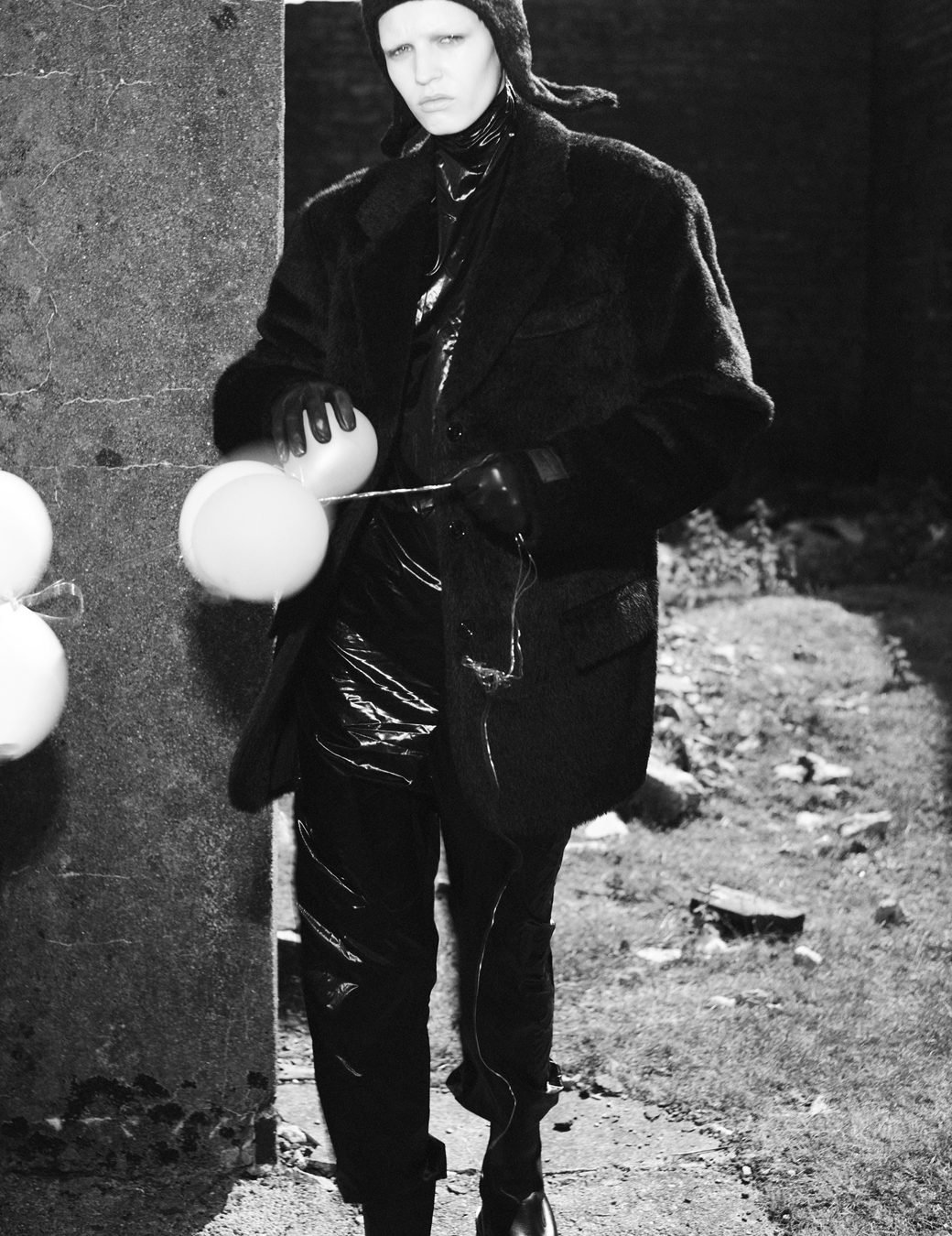

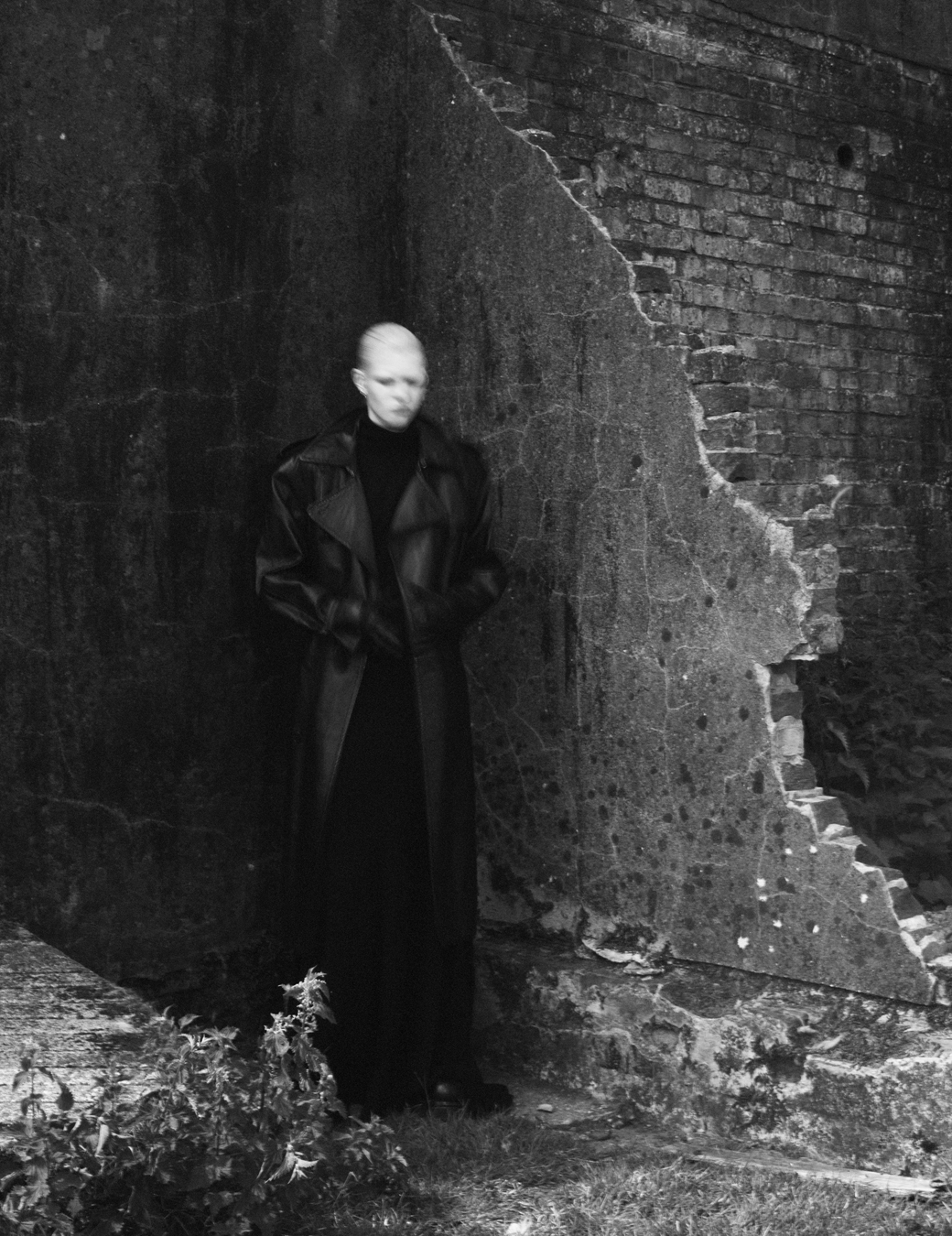

Photography David Sims

Fashion Alastair McKimm

Hair Duffy at Streeters

Make-up Lucia Pieroni at Streeters

Nail technician Ama Quashie at Streeters

Photography assistance Dale Cutts

Digital technician Luca Trevisani

Fashion assistance Madison Matusich

Hair assistance Lukas Tralmer

Make-up assistance Lois Moorcroft

Production Partner Films

Casting director Samuel Ellis Scheinman for DMCASTING

Models Elio Berenett at Next, Camille Chifflot at Supreme