Voy-nah-ROH-vitch: this is how you pronounce the surname of one of America’s most iconic visual artists, David Wojnarowicz, though most don’t try to wrap their tongue around it. Chris McKim, the director of a new documentary that dissects David’s life from his birth to untimely death, knows this, and so he doubled down when it came to giving his movie a title. Said documentary, released this Friday, is called Wojnarowicz: Fuck You F*ggot Fucker. “It is kind of naughty of us to name a film a word most people can’t say, [and give it] a tagline that people shouldn’t say,” Chris laughs.

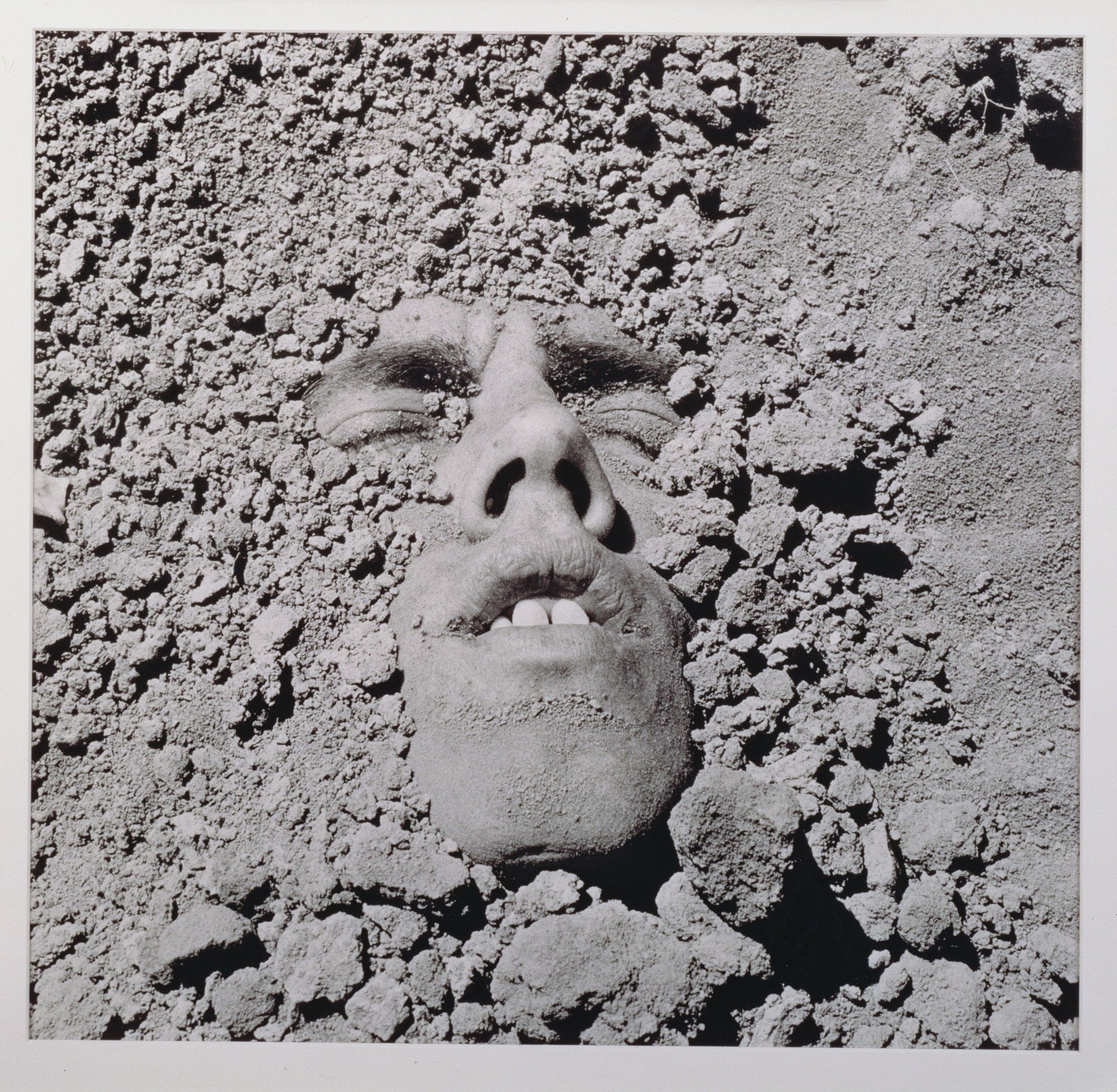

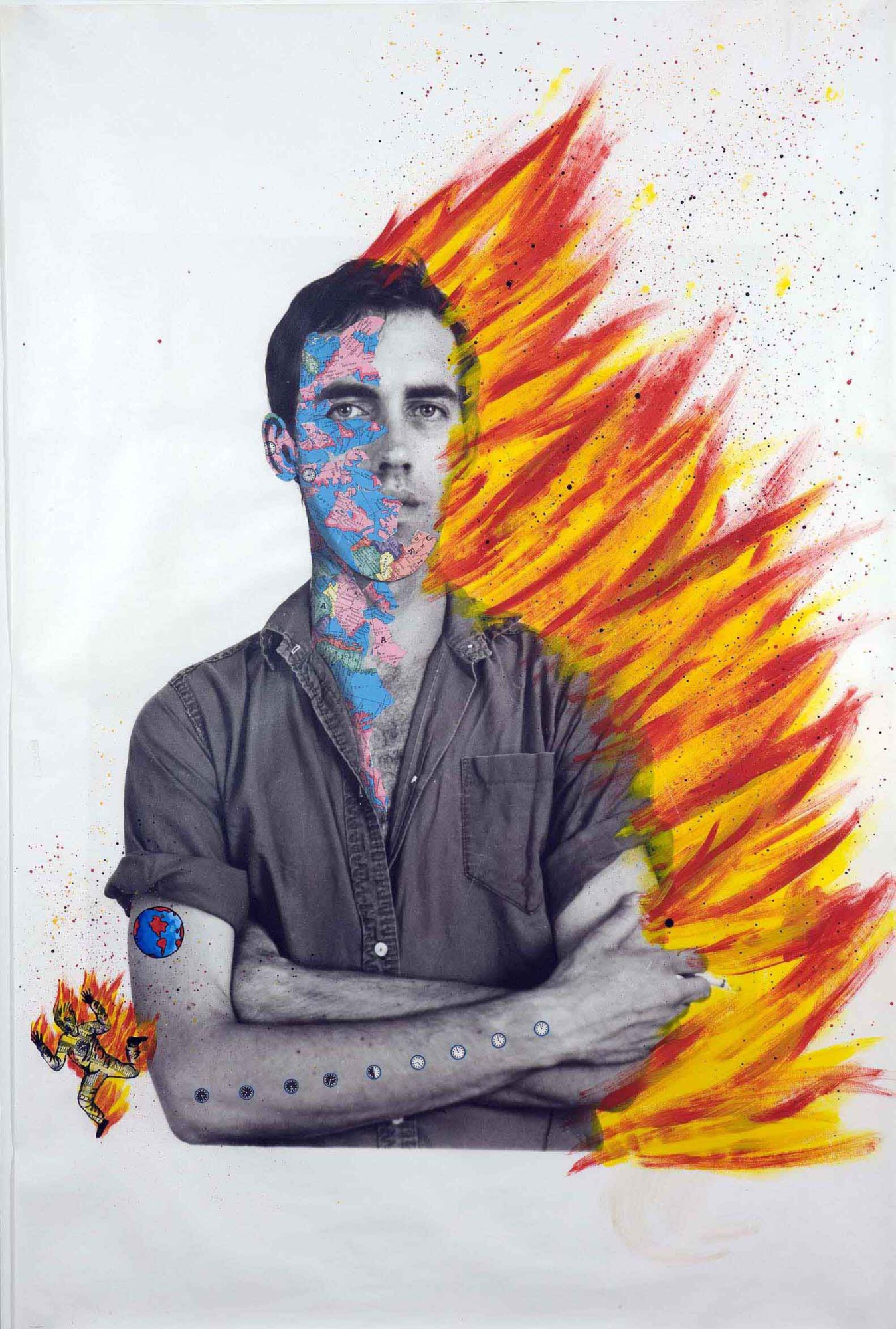

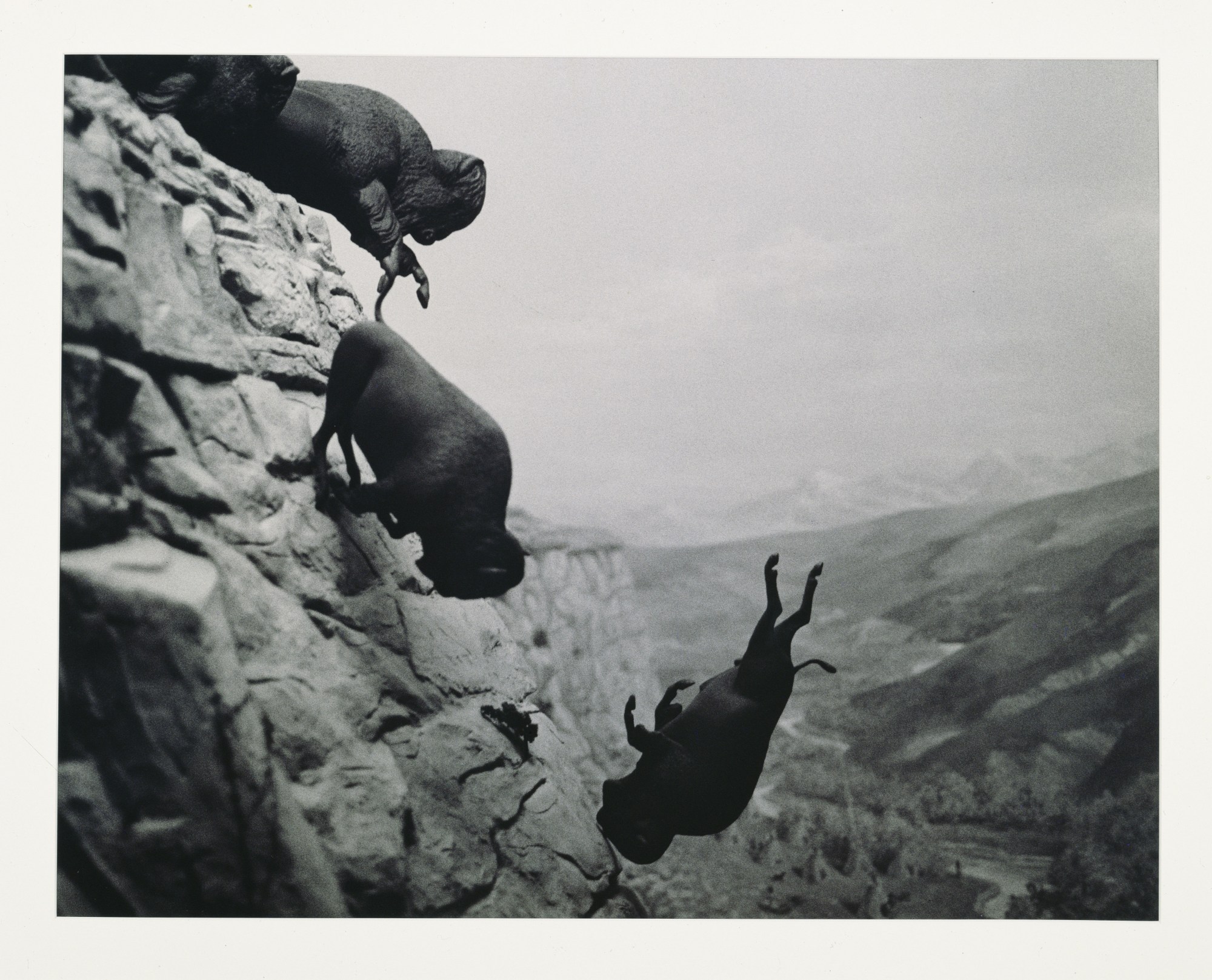

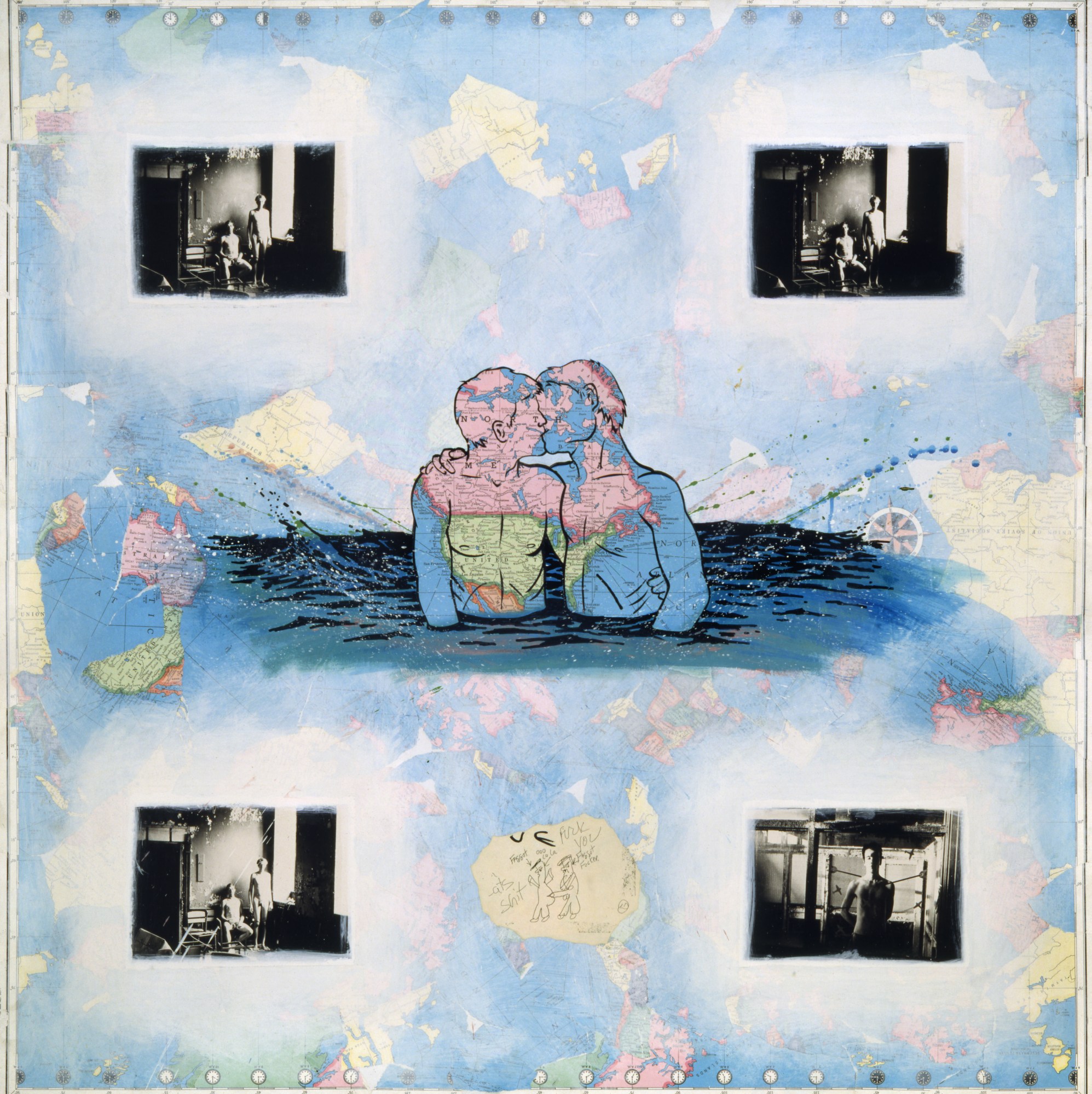

A tagline from one of David’s most famous works, it’s a title he’d likely approved of if he were around today. A political queer provocateur, he earned a reputation in the 1980s East Village art scene in New York for making mesmerising art from grotesque materials: trash, insects, bovine blood. He took pictures, made paintings and installations that adorned the basements of Wall Street bankers, all the while documenting his life on a series of cassette tapes that still exist in his estate’s archives today. For Wojnarowicz, Chris spent the best part of two years poring over these tapes, forming a stunning eulogy of David’s life and work, sewn together with his voice and those of his most important friends: the late Peter Hujar (who died of complications relating to AIDS, like David), writer Fran Lebowitz and photographer Nan Goldin.

In this interview, Chris describes the all-consuming nature of this two-hour homage to David’s life, speaking to legends like Nan and Fran, and the political legacy of his work.

How intimidating was it to have to make art from the life of an artist so prolific?

Very! David being such a specific type of artist, it took me months to not feel like he’d hate me for this, but I kind of got over that. All I could do was just listen to the audio and his words and try to be true to him in that way. That took the sting off. In some ways, he guided the narrative.

Can you recall your first memories of David’s work?

I’ll be honest, all previous knowledge has been blown away through the process of making the movie! I think because I had so much access to his audio I spent a lot of time with him, even though I didn’t fully “meet” him until 25 years after he died, through his words. Having access to all of those cassettes, and filling my iPhone with them and walking around in New York or here in Los Angeles [listening to them], it kind of transformed the experience and my knowledge of him. I never got to sit him in a chair and ask him questions, but he shared so much of himself [in those tapes].

It feels like David’s life was so poetic: a boy from Buttfuck, Nowhere moving to New York and catalysing a gearshift moment in that art world. Did you always want it to start from those early days through to his death?

I had read the highly detailed biography, Fire in the Belly by Cynthia Carr, and that was a great overview for me going into the project. In terms of the film being made chronologically, it wasn’t always the plan, but because there was so much going on and it was so chaotic, it seemed to ground everything. David shared so much of his personal journey that we had an opportunity to see how he paved his way in life through art, and use that art as a form of resistance.

Was there a certain period from his life you felt you could turn into its own film?

There are a lot of tapes from exactly 40 years ago this week, and some of those tapes are in the film: the conversations surrounding Peter Hujar. He gets so much important advice from Peter, but all those tapes chronicled this kind-of affair David was having. I wanted to see if there was a way we could set the film in [that time period] and find ways to observe other elements of his story, but in the end it felt too insane! The minutiae of things got me really excited.

What was the experience of having conversations with elusive people like Fran Lebowitz and Nan Goldin like?

I was running around New York for three weeks with the audio equipment in my backpack. I’d start the day in Kiki Smith’s studio and then I’d meet Judy Glantzman, then I’d dash off to Brooklyn to go to Nan Goldin’s. To be in Nan Goldin’s apartment was a special experience. She was bringing out the pieces [of David’s] she had and art from other artists as well. At the same time, Fran Lebowitz was as amazing as you’d imagine, I met her in the Maritime Hotel in New York. Of course, Fran doesn’t have a cell phone or email. Setting up the interview, you talk to her person and they’re like ‘As soon as she gets in the car, no one has any access to her, you have to be downstairs and meet her on the street’. She spoke about David, Peter and everything you could imagine right up until her last cigarette before she got into her car on her way home.

There have been attempts to make biopics of David’s life that were poorly reviewed upon release. Do you think there’s scope to make a strong biopic about a figure like David? What stands in the way of that?

The spirit of David Wojnarowicz coming back from the dead might stand in the way of it! There’s always an opportunity to show shades of who a person is. That’s what we do in this film, but David was complex — if not for having the opportunity to let him speak for himself in this film, knowing how these films are normally made, I don’t think I would’ve been able to show elements of David in ways we were able to. It’s interesting, I wonder how he’d feel about that.

What role do you feel like this film plays in upholding the memory and legacy of people like David, who helped define such a staunchly political era of queer art?

It was important to me to show David for the queer hero he is. Growing up in the middle of nowhere and looking to the big city as a young homosexual in a pre-internet era and finding your place, wanting your work and your time to mean something seemed so relatable to me. Teaching himself art and making a real point to make that art mean something… that, to me, is a big part of the film. In some ways, without knowing how we’d get there, it was something I had in the back of my head. He says things so clearly. Anytime we got ourselves into a corner with the film, we’d just listen to five minutes of some random tape and David would say what we were looking for.

In the closing minutes of the film, he says: “If the work we make is art, this doesn’t contribute to the resistance for helping a system of control become more perfect”. I think that’s important now more than ever, as queer people, Black people, all sorts of disenfranchised people, band together, to have an opportunity to show people someone who’s lived it and used art to make himself a better person, and to make a difference.

Wojnarowicz: Fuck You F*ggot Fucker is available to stream via Kino Marquee from 19 March. Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more on art and movies.