Anyone who happened to be loitering in the London borough of Greenwich on the evening of 16 January may have spotted a strange sight. Ten or so individuals, faces daubed in brightly painted patterns, winding their way in complete silence through rain-slicked streets, passing the borough’s sleek residential new-builds and empty redevelopment sites.

But this wasn’t some London-based subset of juggalos. This was the monthly outing of the Dazzle Club, a collective of artists using anti-facial recognition paint and choreographed walks to explore surveillance and public space in the 21st century. And I was along for the ride.

The Dazzle Club is a relatively new project, albeit one that’s already attracted an intense amount of interest, thanks to sitting at a particularly hot-button intersection of art, politics and activism. It’s a collaboration between two different collectives and formed by four founding artists, Emily Roderick, Georgina Rowlands, Anna Hart and Evie Price. As a duo, Emily and Georgina focus on performance-based work and curation questioning surveillance politics and cyber-feminist theory under the name Yoke Collective. Anna and Evie represent Air, a more sprawling group of artists who explore existence in the everyday and the concept of being ‘public’.

The Dazzle Club emerged in response to a letter from London Mayor Sadiq Khan sent in August 2019 that questioned the use of facial recognition technology in King’s Cross by developers Argent.

“It’s Georgina’s brilliance really,” says Anna of the Dazzle Club’s origin story. “I saw this letter Sadiq had written to Argent. I’ve been working in King’s Cross for nearly a decade so had a real interest, so I flung it over to Gina and said ‘What do you think of this?’ and she flung it back saying ‘I’ve always liked your silent walks; what about a silent Dazzle walk?’”.

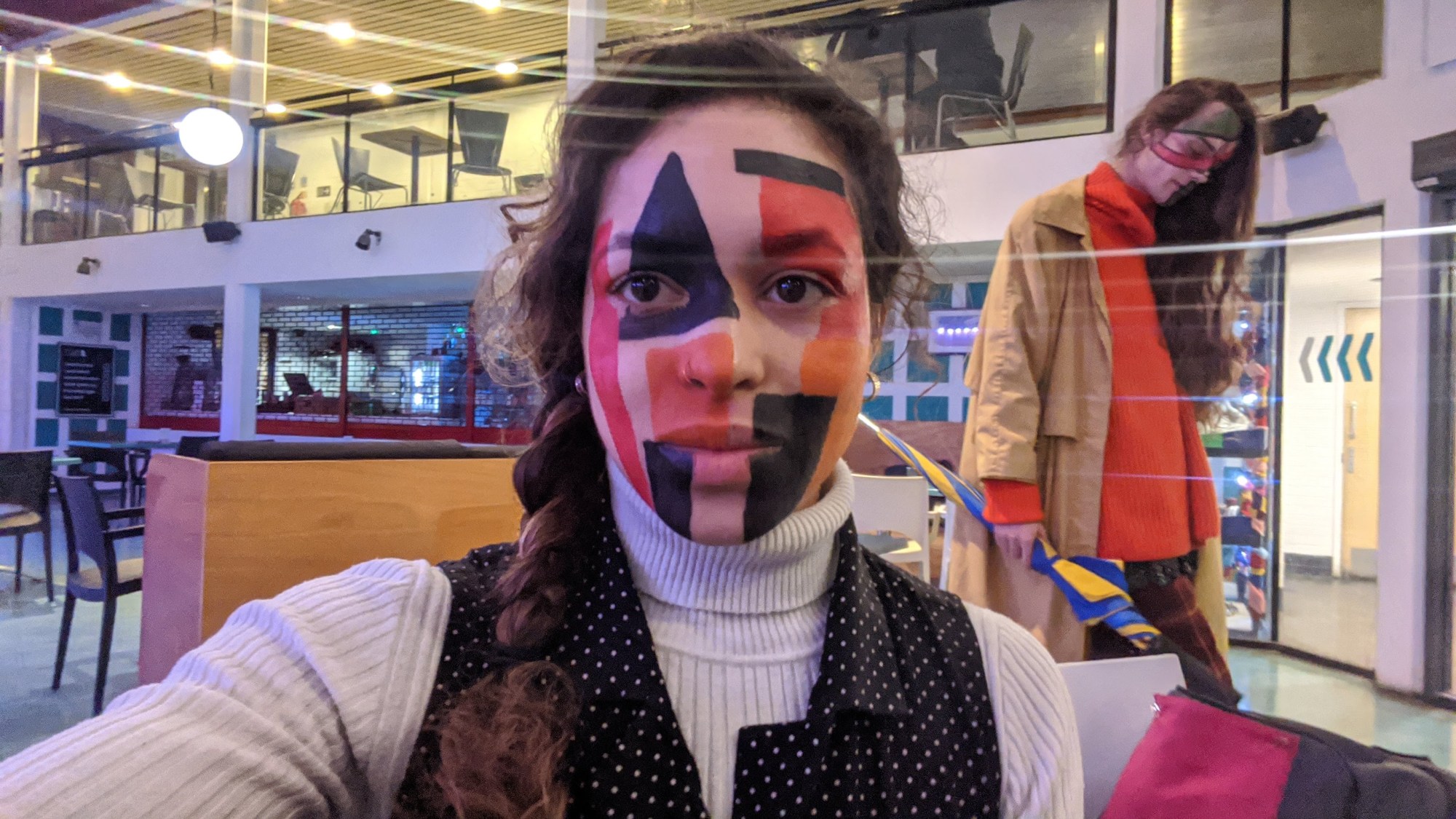

‘Dazzle’, for the uninitiated, refers to ‘CV Dazzle’ (Computer Vision Dazzle’ if you nasty), and is a type of camouflage makeup created by artist Adam Harvey in 2010. Harvey’s lookbooks expand Dazzle beyond just makeup; models have hair moulded into spikes that block out their faces and body jewellery occasionally used in lieu of paint. But the Dazzle Club opt-for a more practical paint-based approach. The trick to Dazzling, as they call it, is to break up the face.

“You’re trying to obscure the natural highlights and shadows on your face,” says Georgina. “Cameras will reduce you down to pixels. They’ll pick up the bridge of your nose, your forehead, your cheekbones, your mouth and chin. So you have to flatten your face and obscure it.”

The most effective way to do this is via strong lines across the face, mouth and nose that divide up facial symmetry, preventing the facial recognition software from fitting the puzzle pieces of your face together into a coherent picture. Dazzling isn’t foolproof – when we do a quick pre-walk test, my brand new phone has no problem applying a ‘BABES’ Insta filter to my face – but the Dazzle Club’s main purpose isn’t to cheat surveillance tech. Their project is about using art to question normalisation of the surveillance that’s happening in the first place, and our changing understanding of what it means to exist and move in public spaces in the 21st century, especially while under the increasingly watchful eyes of both private companies and the state.

“London is the second-most surveilled city in the world, only beaten by Beijing. There’s an estimated 420,000 CCTV cameras watching the city’s eight million or so inhabitants go about their daily lives. Somehow, this is normalised.”

When I join preparations for their January walk, Evie takes me through the process. It’s like “handwriting” she tells me, with each artist developing their own style. I’m quickly rendered a mosaic of red, black and orange blocks. Her own face is transformed into a series of primary-coloured squares and lines that seem vaguely familiar; it’s only later when a bloke in the pub calls her a ‘Mondrian’ that I realise why.

Once Dazzled, the group take to the streets for an hour long walk starting at 6.30pm which sees the club members, guest artists and any additional attendees led around an area of the capital in complete silence. These are no casual strolls. Since August 2019 the Dazzle Club has walked through some of the most heavily surveilled areas in Britain. Each walk is carefully choreographed and can take up to weeks of planning, with a different Dazzle Club member or guest artist taking the helm each month. Though, as Anna explains, technically they don’t even need to intentionally choreograph the walks to pass by certain types of cameras or surveillance technology; it’s so ubiquitous that you couldn’t escape it if you tried.

Anna says she focuses on “elements of contrast” in landscapes when choreographing routes, such as the walk she lead through the backstreets of Southwark, which began with cameras clustered together and mounted low on small thresholds, but ended on the steps of huge institutions of power like the Bank of America and St Paul’s. Evie’s King Cross walk ended with her pulling up a publicly available live streamed feed from Granary Square (viewers can literally watch any action happening in real time via a mounted camera).

Georgina was inspired to plan her walk in the privately-owned Canary Wharf estate after reading about an office worker there who was subject to a series of bizarre over the top regulations following a stealing row. “The worker forgot to scan something in the self-checkout, was forcibly removed from the estate and banned,” she tells me, sounding amazed. “But because he works in an office there, he has to be walked in and out of the estate every day and couldn’t walk in any other area because it’s private land.”

Attending a walk, just some of the layers present in the Dazzle Club’s project become visibly apparent. Once you step out into the street, Dazzle on, it is impossible not to notice the cameras, to wonder who is sitting in a poky room somewhere watching you make your way across the city. But the walks also lay bare the increasingly few true public spaces in London. During our Greenwich route, we pass through many pseudo-public spaces, places that appear to be public land but actually belong to private landowners (these are commonly nicknamed ‘POPS’ – privately owned public spaces and the likes of Granary Square and Bankside are among their number). Sometimes they’re signposted; most of the time you can pass through unaware that you’re walking on land subject to regulations drawn up by the owner, that they are not forced to make public and that they can alter at will.

London is the second-most surveilled city in the world, only beaten by Beijing. There’s an estimated 420,000 CCTV cameras watching the city’s eight million or so inhabitants go about their daily lives. Somehow, this is normalised. But a fresh row has broken out in recent years, as both private companies and the state have sought to enhance the technology already used to watch over the city.

It came to a head last week, when the Metropolitan Police announced they were going to be rolling out live facial recognition — a technology with so much potential for abuse the European Commission are currently deliberating a ban on its use for the foreseeable future — across the city to fight crime. Human rights groups immediately expressed outrage, citing problems like inaccuracies in the tech — most worryingly exemplified by a racial bias built into the tech that results in high error rates of facial recognition when it comes to non-white faces. One MIT study found that facial analysis software was inaccurate up to 34% of the time when it came to identifying dark-skinned women, compared to 0.8% for light-skinned men. The Met’s own facial recognition system has an 81% rate of inaccuracy, according to an independent report. These concerns are also paired with natural fears that the widespread use of facial recognition is a violation of basic privacy rights and will create a ‘digital panopticon’, where individuals will feel under watch at all times.

The Dazzle Club are acutely aware of the potential of their project to come into bruising conflict with the state; their Canary Wharf walk saw them stopped and questioned by security guards multiple times. Knowing this will be a feature of many of their walks, they’re currently looking to add a permanent legal advisor to their team. A potential collaborator has already requested any work they do with the collective is done under a pseudonym, worried that their immigration status could be affected by engaging in art that grapples with such a controversial topic. And the collective also have clocked the need to include the voices of those most affected by the technology in their artistic response to the issue.

“It is really important to us to work with [non-white] artists on this,” says Anna. “But we need the funding first before expanding.” While they seek the money, they are focusing on continuing the monthly walks and letting the project develop at its own rate. Keen to keep walks small (“10 is a really lovely number to work with,” Anna says, of the optimum amount of Dazzlers), they accept that with media interest, attendance is likely to increase, in which case a ticketed system will probably be implemented. They’re also considering taking Dazzle to the London Underground. But at the heart remains the hour long walk of invisibility.

“This is just the beginning,” Anna finishes. “We don’t know where this could go — but we’ve given ourselves the space to find out.”

The Dazzle Club meet every third Thursday of the month; the next walk is in Shoreditch on 20 February, details here .