Swept away by the waves of shows, presentations, events and product drops that accompany fashion months, the distinct memories of collections are often washed away. However, those rare moments in which an artist creates something that transcends the rag trade and forces you to truly look, feel, think and react, live long in the mind and should be celebrated. There are countless designers and an ever growing number of shows but there are few artists and even fewer moments. As the dust settles on the menswear season, Grace Wales Bonner’s spring/summer 16 performance still occupies my thoughts, so rather than move on, let’s look back, linger and savor.

Ultimately, Grace repeats the words of poets and thinkers that have long inspired her but rather than mimic the likes of Moten, Hemphill and Baldwin’s declarations and prose, she stitches her words from linen, velvet, mother of pearl and silks. They are no less moving and no less powerful. Grace is an artist, ethnographer, poet, dreamer and academic, who chooses menswear as her medium as her craft celebrates, confronts and challenges cultural codes. There’s a softness and sensitivity to her work that draws you in. Her whispers echoed through every facet of the experience. The collection, soundscape by James William Blades, casting, set design and accompanying Ditto-published zine could each be enjoyed individually but experienced together, the realness of Grace’s well-crafted world became so clear that you can almost see through her mind’s eye.

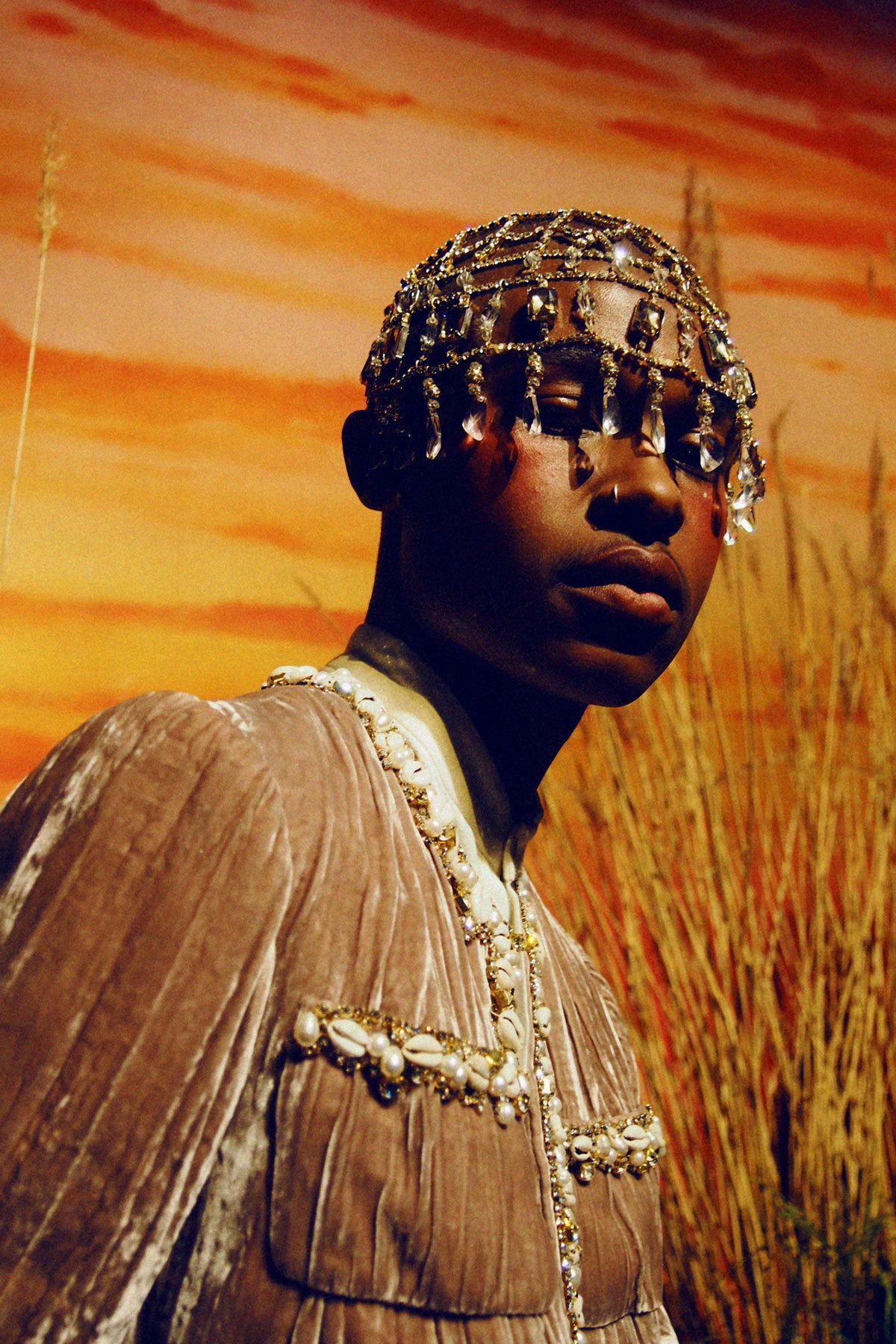

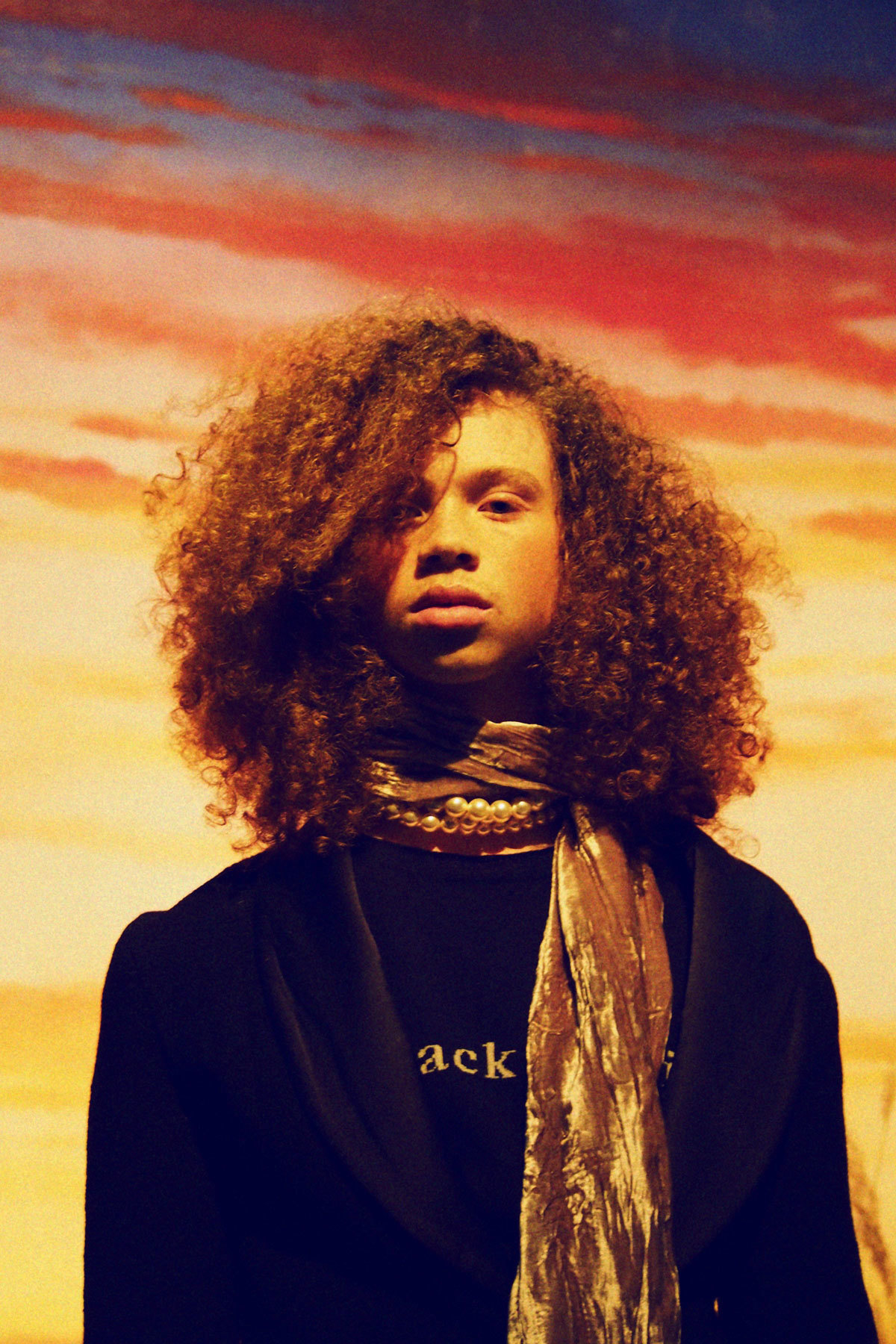

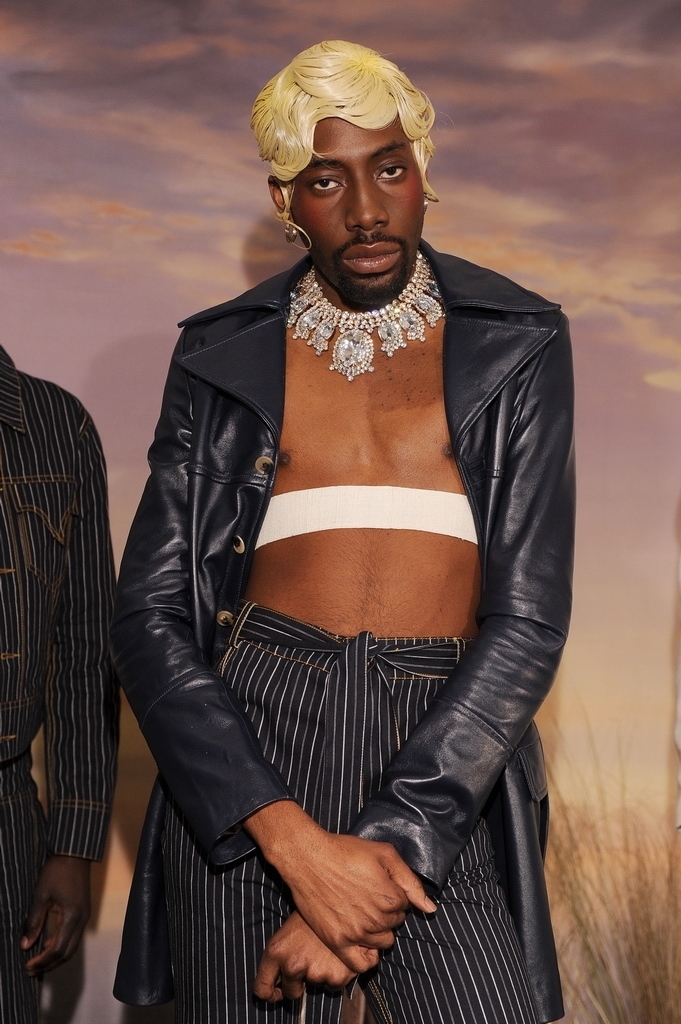

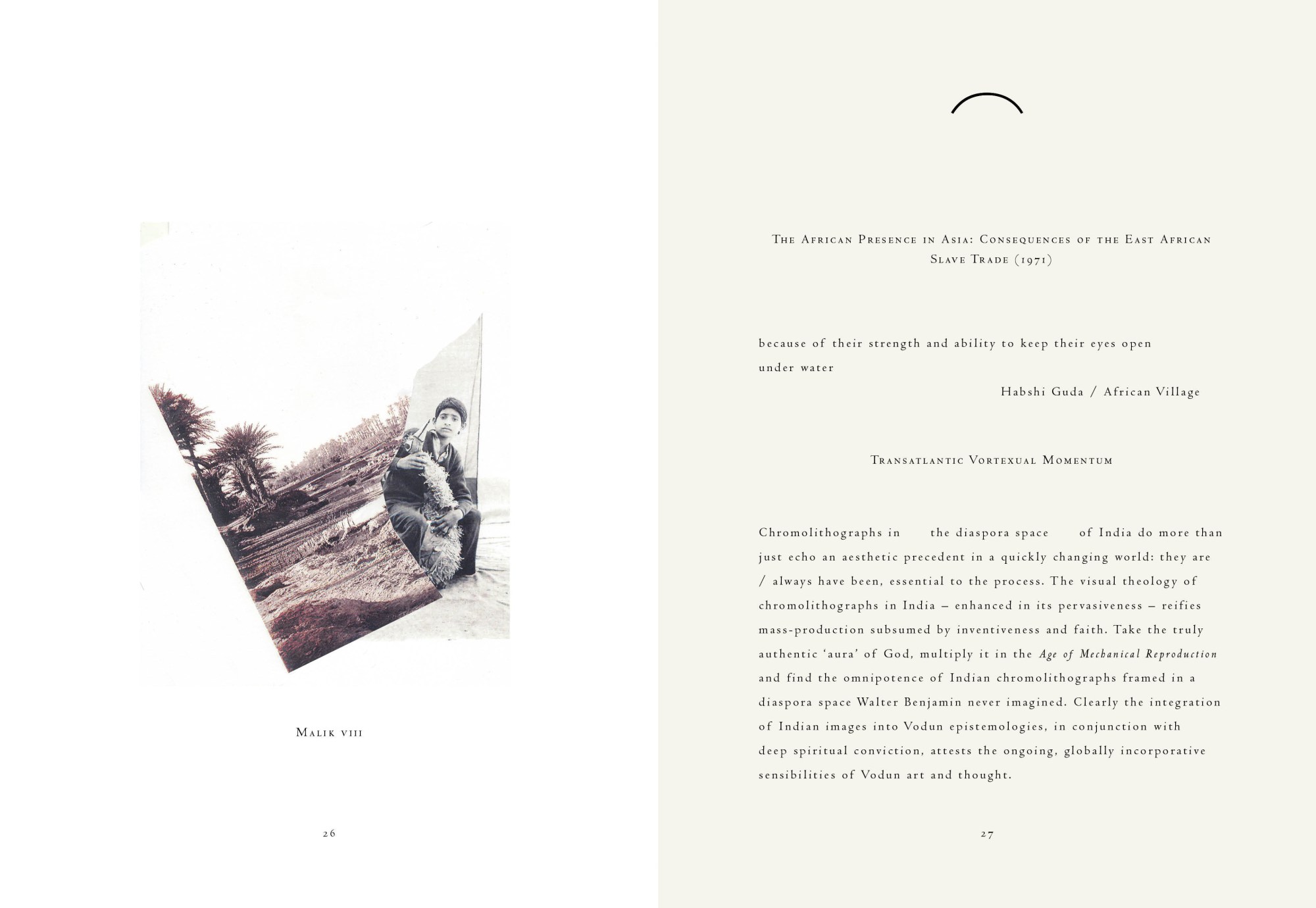

Evolving the black hymn she presented last season (and returned to during her acclaimed Fashion in Motion series at the V&A), Wales Bonner delved deeper into her hybrid of cultural representation. Inspired by the streets, sound and style during a recent trip to Dakar, Grace breathed fresh life into the 16th century story of Malik Ambar’s passage from Ethiopian slave to ruler in Western India. Through Grace’s study of beauty, we were able to see Malik’s evolution, feel a sense of the struggle of black history, the postures of royalty and the essentialism of black dress. Following the African diaspora across the Indian Ocean and beyond, she used every nook of ornate setting of the ICA’s Nash Rooms to transport the audience deep in the story she weaved. As it’s a story worth repeating, i-D exclusively share the soundscape, take a peek inside the latest issue of Everythings For Real and sit down with Grace, James and Ditto’s Ben Freeman to lose ourselves in her world, yet again.

Grace, how did your recent trip to Senegal, and Dakar in particular, inspire Malik?

I was inspired by the natural rhythm which felt like a foundation to everything; the talk, the walk, the way people wear clothes. I was attracted to the market space, and the shifting of cultures and traditions that occur there. The sounds – the prayer calls, the intonation of different dialects, sounds of crackling radios. The market was where you saw the real fashion; a powerful appropriation of clothing; men would wear women’s T-shirts and traditional robes with fake American trainers made in China. I loved the way people put things together with such conviction, it made it something completely new and the men there were so tall and elegant. What I was trying to do this season was reflect that immediate collision; it was a collection of elements that clashed together to create something elevated.

How conscious are you and how important is it to you that you transport viewers into your world?

I felt a real sense of serenity in Dakar, it was exactly where I needed to be at that time. It felt important to translate this sense of quiet and calm in the ICA. We were thinking about deconstructing a Maharaja’s palace. It was about creating space to reflect. I didn’t want people to just be able to rush through and leave. It was about giving the idea space and time to be, and giving the audience that.

I wanted to create a broader world of representation, to explain the same story through different mediums, which is why collaboration is so important to me. Using contemporary dance was a way to physically interpret the story of Malik, the struggle of black history and the elevation of this character.

I personally went on a journey, after speaking to Lulu, I left in tears and that was largely down to you. How important was the soundscape (including your own recordings) to this journey?

I wanted it to feel authentic. I wanted the soundscape to transport you to that market scene – to blown out car radios, local commotion and the polyphonic harmonies of street life. Echoes of the black struggle are embedded in the sound; Amiri Baraka and James Baldwin reflect that even in their intonation. The soundscape was an important part of the research, an assemblage of black histories, it was asking what is black sound? What is its rhythm? And it also reflected the Indian influences that translate in contemporary African music as a mirror to the story, i.e. referencing Hausa songs (inspired by Bollywood films) and the work of Thione Seck (a Sengalese singer who works with Arabic and Indian scales).

James, was there a strict brief or were you free to interpret her vision?

Grace knew what she wanted, but there was no strict brief. I would compose out a sketch, send it to her and she would say what she liked/didn’t like and we would repeat that process until we built up something that worked. When you work with someone who has such a clear vision, it’s hard to completely convey that vision, Grace was very open to interpretation and she allowed me to experiment with different ideas. Some of them were completely off, others were great. I started just by listening to the scrapbook of music, recordings and speeches Grace sent me.

Can you talk us through some of the samples you mixed, for the example the It’s called Dope, the Brother to Brother skits and Grace’s own recordings?

The samples we mixed in were chosen for different reasons. The context of the words, the phonetics of the way the words were spoken and the unique rhythm of the sentences. The Brother to Brother section was from the iconic black queer film Tongues Untied by Marlon Riggs, which talks to the history of black representation and about bending notions of blackness. Musically, it’s an entrancing moment of repetition. Grace’s own recordings are dotted around the place, and that was a really special thing to be able to work with. It adds an authenticity to the soundscape that’s hard to get without.

Grace, could we talk a little about your presentation of gender. Your man is so different to the hegemonic portrayal of tough, aggressive and ‘street’ guys. There’s a quiet, sensual power to your men. Where does this come from?

The men in my life are far from those images of masculinity that are over-exposed. I guess I am trying to represent something that is the polar opposite and I am interested in sensitivity, elegance, beauty and sensuality.

That’s reflected in the cast.

I worked with Joyce NG on the street casting and she found some beautiful young Somali models – I was really excited to work with them as they were so elegant and had a real serenity about them and they are completely unrepresented in fashion. It was also great to work with more Indian models this season who were able to carry the regal qualities really well and really got on board with the story.

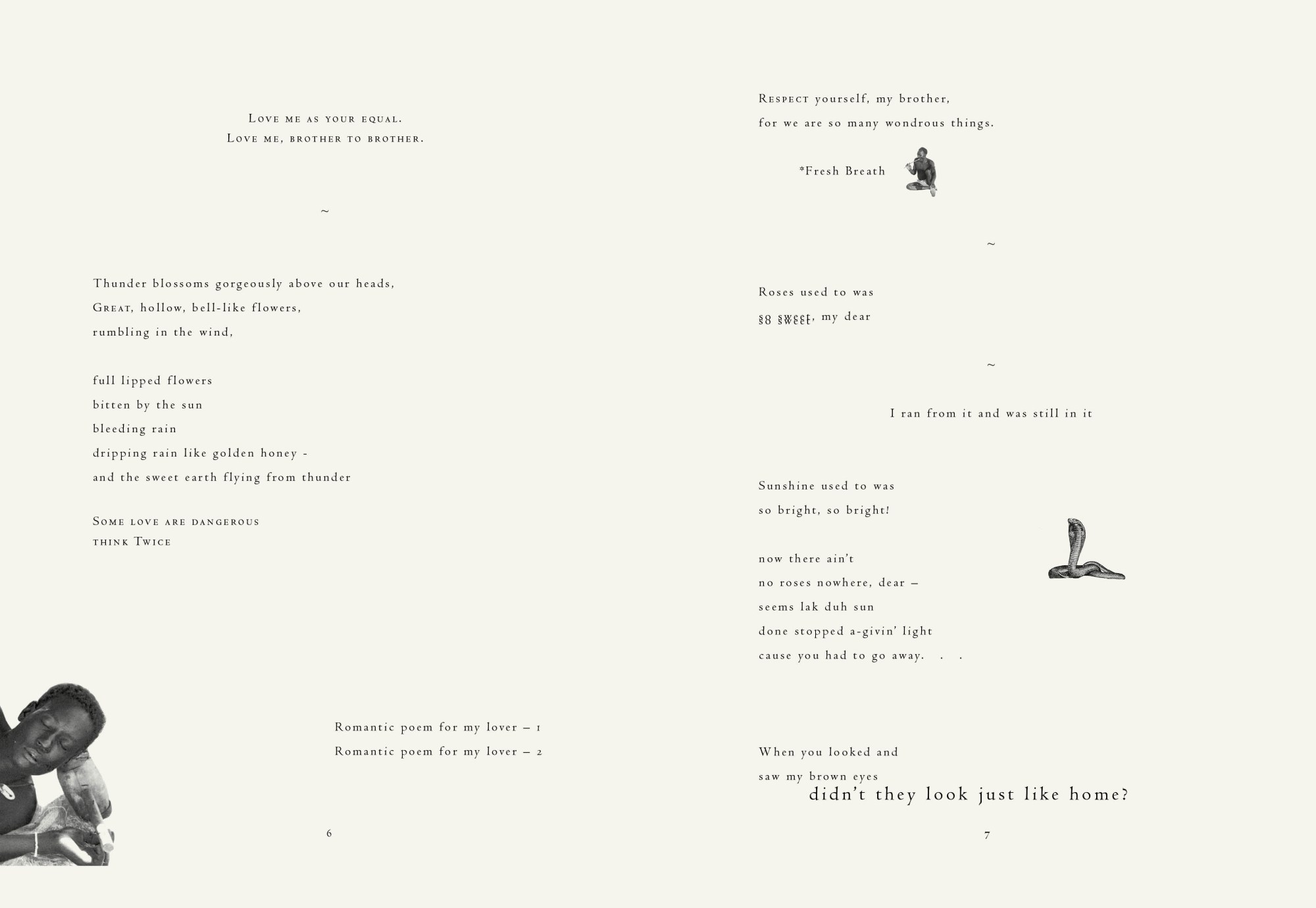

Much like the soundscape, the latest issue of Everythings For Real is a collage that adds yet another layer to spring/summer 16. Could you talk us through the process of collating the imagery, poetry and prose?

A lot of the imagery is collected from first-hand sources, out of print books and a large library of printed material I collected in Ghana, like washed out DVDs, romantic pamphlets, gin sachets and homemade mix tapes. We really study the found material and observe how it’s put together. It’s also about thinking about the vernacular of these materials and using that to communicate something in my own way. Along side the more playful elements, like a manual I found on “how to kiss your love” in Accra, the book is collaged alongside more serious black literature. As a theme I was looking at the idea of a black rhythmicality that underpins black love – Fred Moten’s work as well James Baldwin and Essex Hemphill’s work were really important to this aspect of the texts. I also interspersed the book with academic and more sporadic reflections on the African diaspora in the Indian Ocean, so there are two parts to the research. The casing of the book itself is a more modern reflection on that in the similarities between Bollywood and Nollywood cultures. Like the soundscape, and the collection, the book becomes a collage of all my inspiration, some of it serious, some of it more playful. I try to create an abstraction through these found artifacts and voices to create a new narrative.

Ben, how would you describe the working process?

When we work with Grace, we see the publications as a part of her collection. They communicate in specific ways; books are intimate and the reader gets to engage with the poetry, spoken word and other texts that inform Grace’s collection in a form that she directs. They have informed something of a developing direction for us: luxury zines, zines with very high production values that match her craft in the apparel she makes. We get together and pull inspiration from a broad range of material, from Nigerian pirate DVDs to American civil rights poetry via anthropological African studies and fetishes. We then research production methods and materials that will suit, and put them all together in a coherent and simple way.

Is there a particular line or image that you’re most proud of/excited by/inspired by?

Everythings for real pretty much encapsulates it. It is a quote from an Amiri Baraka poem, In Our Terribleness (1970), it was important to include the grammatical error as it is about celebrating the beauty of it all.

Grace, I wanted to ask how you feel about your work sparking conversations on gender, sexuality, race and class. Does seeing your work viewed in a wider political and cultural context excite or frustrate you?

I think it’s good to get people talking and I think it’s equally important to keep putting images out there of a broader spectrum of blackness and masculinity.

Credits

Text Steve Salter