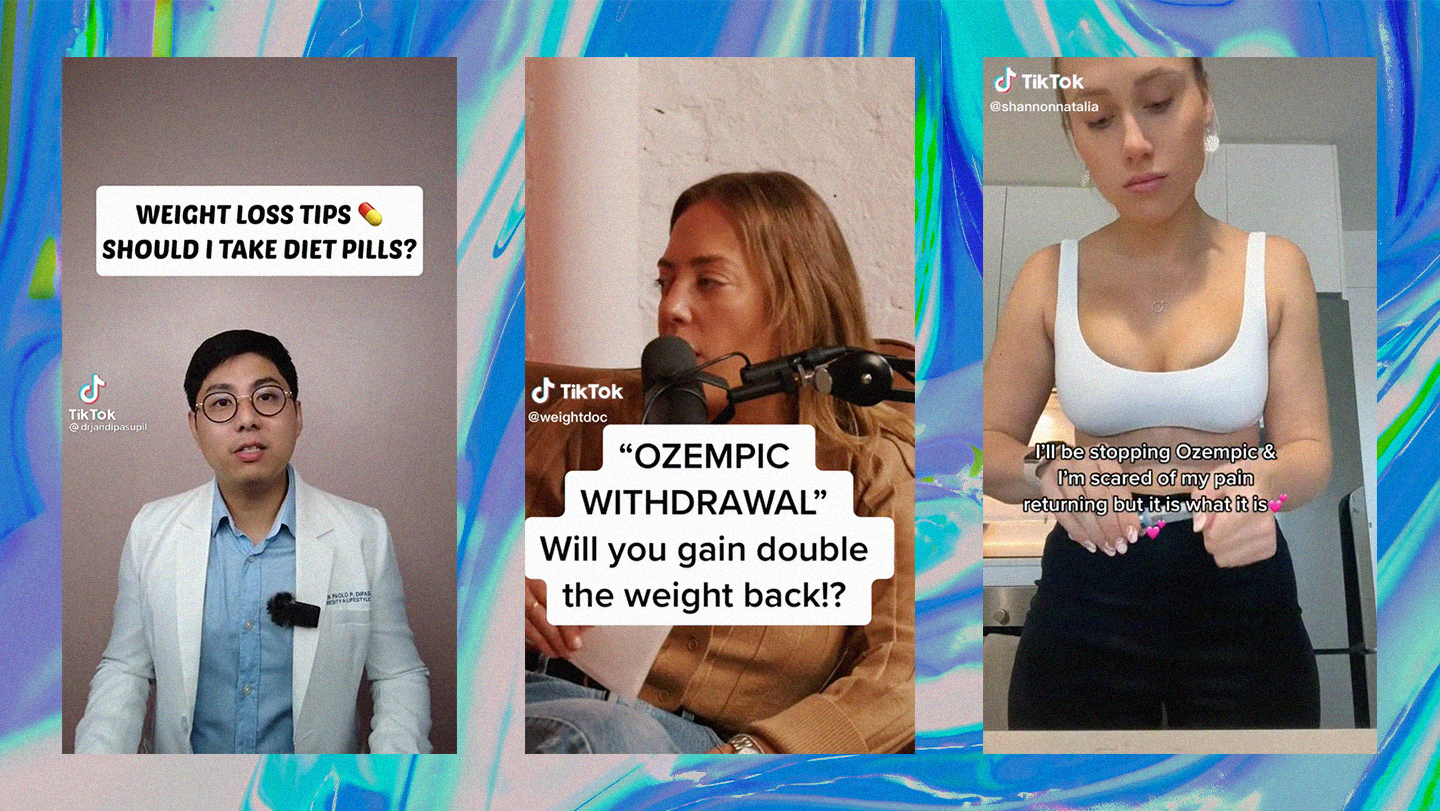

Since generating a quiet buzz among Hollywood’s elite, Ozempic has become the internet’s diet drug du jour. On TikTok, videos of people gushing about Ozempic-assisted weight loss have racked up hundreds of millions of views. Elsewhere on the internet, rumours that Ozempic is responsible for dramatic body transformations of celebrities run wild, such as the (unfounded) rumours speculating Kim Kardashian used the drug to fit into Marilyn Monroe’s dress at the Met Gala. Elon Musk has publicly praised the drug. If Ozempic was once Hollywood’s ‘secret’ weight loss drug, in 2023, it is anything but.

Ozempic – the brand name for the injectable-drug semaglutide – works by mimicking a hormone that regulates appetite to create the feeling of fullness. The drug has not been approved for weight loss, only for the treatment of diabetes, and questions remain about its safety and efficacy as a diet pill. Perhaps most concerning is how its recent popularity as an “off-label” weight loss pill has sparked a global shortage of Ozempic, leaving people with diabetes who actually need the medication without it.

Subscribe to i-D NEWSFLASH. A weekly newsletter delivered to your inbox on Fridays.

The rise of Ozempic has often been seen as part of the reemerging supremacy of thinness, along with TikTok trends such as ‘heroin chic’, ‘that girl’ and ‘what I eat in a day’ videos. Meanwhile, hospital admissions for people with eating disorders in England have risen 84% in the past five years. It’s worth stating, though, that thin privilege and rampant fatphobia never really went away. Companies who sell drugs used for weight loss know this to be true, and capitalise on it time and time again. Yet despite the unceasing demand, and the enormous profits to be made, doctors have become reluctant to prescribe diet pills, and pharmaceutical companies have been nervous about investing in creating new ones. In fact, only one drug could be prescribed in the UK between 2010 until last year.

There is, of course, good reason for this. If the chequered history of diet pills tells us anything, it’s that they don’t work – and that they can be dangerous. As early as the Victorian era, people have been experimenting with diet pills and potions. As author Louise Foxcroft details in her book, Calories and Corsets: A History of Dieting Over 2000 Years, ads for diet pills started to appear in magazines following the establishment of mass media in the 19th century, often showing “before and after” illustrations of women. Weight loss pills could contain anything from baking powder, to lard and arsenic – which the Victorians took with the knowledge of it being poisonous.

Between the 1930 and 50s, huge amounts of money was being poured into developing amphetamine-based weight loss pills. Researchers had known for decades that amphetamines suppressed appetite, but their use for weight loss only took off after World War II. Patients were typically prescribed ‘rainbow diet pills’ – an innocuous-sounding name for dangerous combination drugs. These included amphetamines, diuretics, laxatives and thyroid hormones that send the body into weight loss overdrive, as well as benzodiazepines, barbiturates, corticosteroids and then antidepressants to counteract some of the other ingredient’s side effects, like insomnia and anxiety.

Too much amphetamine is known to trigger psychosis – everything from paranoia, to delusions, as well as auditory and visual hallucinations. It’s presented in Darren Aronofsky’s psychological drama Requiem for a Dream (2000), where Sarah, an elderly woman, starts taking a colourful ‘rainbow’ of diet pills throughout the day to slim down. This leaves her with terrifying hallucinations and monstrous addiction. Her story ends with a harrowing scene in which she undergoes electroconvulsive therapy without anaesthesia.

Requiem’s dramatisation might be shocking, but it isn’t too far removed from reality. In 1979, the FDA banned amphetamine-based diet pills after they were linked to dozens of deaths. The mid-1990s then saw a surge in popularity of Fen-Phen only for that diet pill to be pulled from the market too because of concerns that it caused serious heart valve problems.

The bad press did little to halt demand though, instead helping to fuel a thriving black market where potentially lethal ‘diet pills’ are sold via social media. The problem isn’t just confined to shady, secretive corners of the internet either. In the 2010s, reams of Instagram influencers – including the Kardashians – began flogging “tummy teas”, often deploying the language of ‘wellness’ over ‘weight loss’. While presenting these drinks as a ‘natural’ alternative, they often had side effects which included nausea, cramps, and diarrhoea. In some instances, they even caused unwanted pregnancies — in 2015, UK-based tea merchant Bootea faced criticism for not making it clear that the tea’s ingredients could interfere with birth control pills, leading some women to fall pregnant (their offspring nicknamed “Bootea babies”).

“Oftentimes, the side effects of diet drugs are known at the start, and they’re thought to be rare,” says Christy Harrison, author of Anti-Diet: Reclaim Your Time, Money, Well-Being, and Happiness Through Intuitive Eating. “And then over time, it becomes clear that many people are experiencing this really severe thing.”

More serious side effects of Ozempic in particular include kidney failure, pancreatitis, thyroid tumours and gallbladder problems. There are also side effects which are not as serious, but still interfere with people’s lives – such as nausea, abdominal pain and cramping all listed as common symptoms. Already, people are beginning to sound the alarm over the drug. Earlier this month, while appearing on the Not Skinny But Not Fat podcast, influencer Remi Bader claimed that she gained “double the weight back” after stopping Ozempic. Her experience is no anomaly: an April 2022 paper published in Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism found that those on a 2.4mg dose of semaglutide regained two-thirds of the weight they had lost in the first year after stopping the medication, and that those who had lost the most weight would then put the most back on.

These warnings are often drowned out on TikTok, however, as the app continues to spread medical misinformation at unnerving speed. The videos which tend to perform best on the platform are those which show the most dramatic weight loss, blurring the boundaries between fact and fiction for the sake of views. For the many people who now use TikTok as their de facto search engine, this creates a distorted picture.

While platforms no doubt have a responsibility to prevent the proliferation of harmful content, addressing the fatphobia that plagues society goes beyond social media. “There’s been this sort of drumbeat of ‘weight loss equals wellness’ for the last 20 some years,” says Christy. “[It is] preying on internalised weight stigma… [suggesting] it’s your responsibility to escape weight stigma, and not society’s responsibility to stop stigmatising larger bodied people by forcing them to have to do these things to change their bodies.”

Christy describes herself as ‘anti-diet’ – which she says increasingly means becoming ‘anti-trend’. Turning bodies into trends plays into the hands of malevolent companies, which for decades have exploited insecurities in the name of profit. As history makes clear, diet drugs will never be the solution to the oppression fat people face.